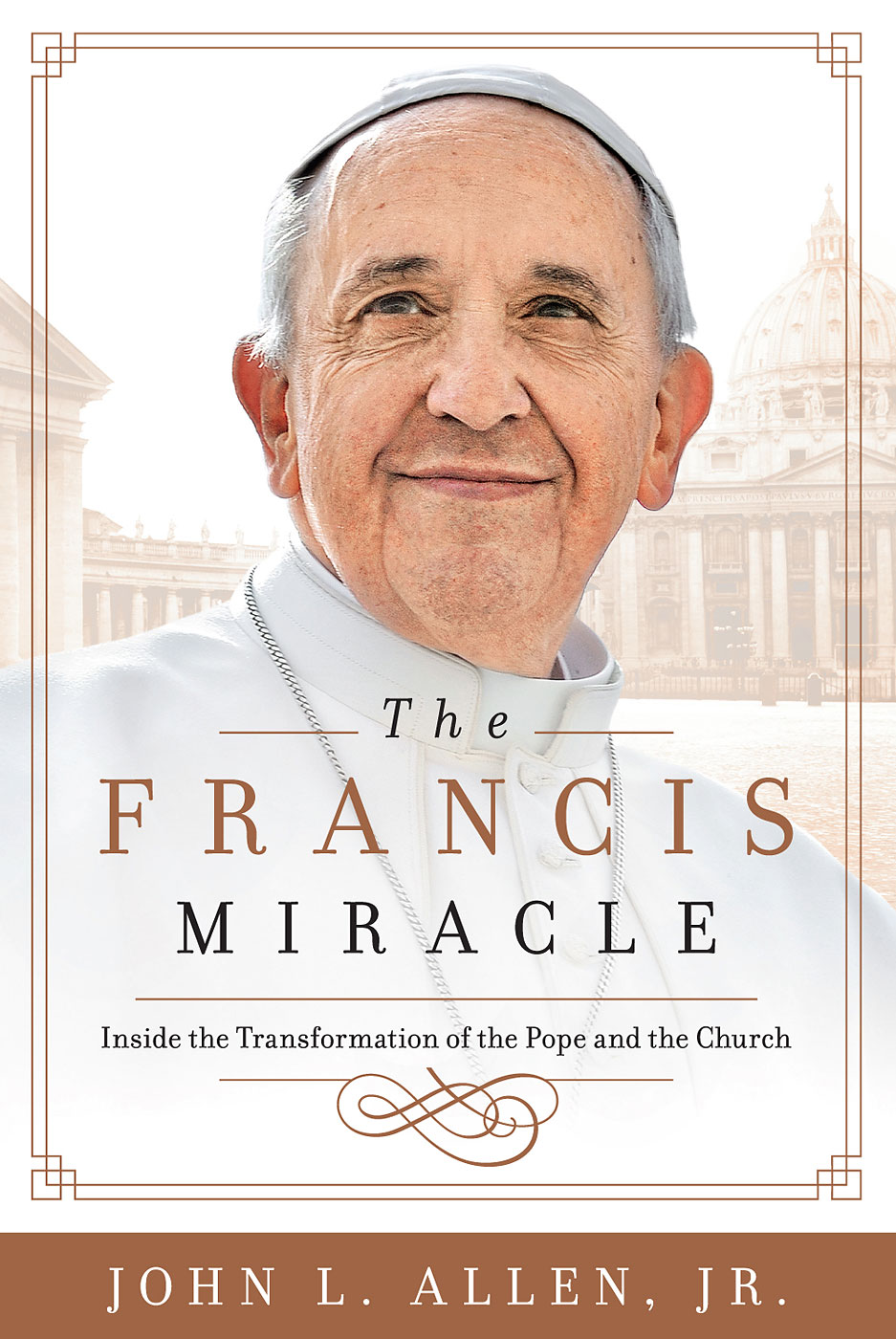

This month marks the second anniversary of Pope Francis’ election. The following is taken from THE FRANCIS MIRACLE: Inside the Transformation of the Pope and the Church by John L. Allen Jr.

Nowhere is the contrast between Benedict XVI and Francis more tangible than in the degree to which the papacy seems to have recovered its diplomatic and geopolitical swagger. The normalization of relations between the U.S. and Cuba in December 2014 came about in part thanks to Francis, who wrote private letters to President Obama and Cuban president Raúl Castro that reportedly helped break the ice between the two leaders.

“Francis is not resigned to a passive vision of world affairs,” said Marco Impagliazzo, president of the Rome-based Community of Sant’Egidio, a Catholic organization active in conflict resolution and peace brokering, in a 2014 interview. “We must prepare for a new age of political audacity for the Holy See.”

Massimo Franco is one of Italy’s most respected journalists, a veteran reporter who has covered all of Italy’s political figures of the late 20th century. He believes that Francis is potentially even more crucial a political actor than John Paul II, who mobilized the solidarity movement and set the dominoes in motion that led to the collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe. “By virtue of being Polish, John Paul was hugely important for the fate of communism and for the reunification of Europe,” Franco said in 2014. “As the first pope from the developing world, Francis is important for every major issue facing the world today: poverty, the environment, immigration and war.”

While Francis clearly wants to deploy whatever influence he can to promote peace, the pontiff is selective about how, and how often, he wades into conflicts.

His first real test came over Syria. In August 2013, after President Bashar al-Assad’s regime was believed to have carried out a sarin chemical attack on opposition areas near the capital, Damascus, Western leaders began trying to foster public support for the use of military force. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said, “History would judge us all extraordinarily harshly if we turned a blind eye,” while President Barack Obama put Congress on notice that he was weighing a “limited, narrow” attack.

As the first pope from the developing world, Francis feels a special responsibility to listen carefully to what he calls the “peripheries,” the places outside the usual Western centers of power. That summer, he was therefore determined to consult Syria’s Christian leadership before reacting. Christians are an important minority in Syria, composing about 10 percent of the population of 22.5 million. The majority is Greek Orthodox, followed by Catholics, the Assyrian Church of the East and various kinds of Protestants. The leaders of those churches told the pope, both in writing and during face-to-face encounters in Rome, that forcing Assad from power was a recipe for disaster.

As they saw it, if Assad fell, Islamic radicals would most likely fill the void—the choice for Syria is not between a police state and a democracy, but between a police state and annihilation. Most Syrian Christians recognize that Assad is a thug but believe that the alternative is even worse. That judgment was confirmed in the summer of 2014, when forces of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant proclaimed a caliphate in northern Iraq, driving tens of thousands of Christians and minority Yazidis from their homes and beheading a pair of American journalists and a British aid worker.

Francis has made clear that the crisis in Syria is a deep concern. He used his first Urbi et Orbi (“to the city and the world”) message on Easter Sunday 2013 to invoke prayer “for dear Syria . . . for its people torn by conflict and for the many refugees who await help and comfort.”

“How much blood has been shed!” Francis said that day. “How much suffering must there still be before a political solution to the crisis will be found?”

In private, Francis stressed during meetings with the Vatican’s diplomatic team that he wanted updates from religious orders and other Catholic groups on the situation on the ground in Syria and told his brain trust that he planned to oppose expanding the conflict in Syria in every way he could. The Vatican swung into action, even dispatching anti-war messages through the pope’s Twitter account.

Although Syria was not the only crisis percolating, Francis felt a special urgency about getting involved because of the precedent of Iraq.

At the time of the first U.S.-led Gulf War there were an estimated 1.5 to 2 million Christians in Iraq. Although they were second-class citizens under Saddam Hussein, they were basically secure. Hussein’s most visible international mouthpiece, former foreign minister and deputy prime minister Tariq Aziz, was himself a Chaldean Catholic. Today, up to 400,000 Christians are thought to be remaining in the country, but many believe the real number is lower, as Islamic radicals have had a free hand in targeting the Christian minority. Francis was determined not to stand by while another Christian community in the Middle East suffered the same fate.

Looking back at John Paul II’s vain efforts to stop the Iraq offensive in 2003, which included dispatching personal envoys to both Sadaam Hussein and President George W. Bush in February and March of that year, Francis felt the intervention had been too political. It failed, in Francis’s eyes, to draw on what’s most distinctive about the papacy as a global force: its spiritual capacity. So Francis opted to do something only a religious leader could do: he called a global day of prayer and fasting for peace in Syria on Sept. 7, 2013, inviting the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics, as well as all women and men of goodwill, to help him storm heaven with prayer.

When darkness fell in Rome that evening, Pope Francis stepped out into St. Peter’s Square to preside over a five-hour prayer service designed specifically for the Syria campaign.

The Vatican estimated the global television audience for the service to be in the hundreds of millions. Thousands of Catholic parishes and other venues staged their own prayer services that day too.

It’s not clear how much credit Francis can claim for halting the initial rush to declare war against Assad. Before Francis stepped out into the square that evening, support for Western strikes in Syria was already beginning to erode. U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron had already lost a vote in the House of Commons seeking support to join the U.S. in military action, and French President François Hollande was softening his earlier bellicose rhetoric. Nonetheless, the pope’s stance was given wide play in the Arab media, and when he visited the Middle East in May 2014, Syrian Christian refugees in Jordan brandished signs thanking the pontiff for “saving our country.”

In June 2014 Francis made an even riskier and more audacious diplomatic foray: an invitation to the presidents of Israel and Palestine to pray for peace in the Vatican, in an effort to revive the stalled peace process.

The invitation was a result of Francis’s May 2014 trip to Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories, the region known to Christians as the Holy Land. The visit crystallized Francis’s reputation as a pope of surprises, because it was punctuated by moments that veered off script and left the pope’s advisers scrambling to keep up.

The shocks began on May 25 when Francis called on Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas in Bethlehem. Afterward, the pontiff was scheduled to proceed to Bethlehem’s Manger Square to celebrate mass for the city’s dwindling Christian population. His route for the short drive took him immediately next to the massive 26-foot-high barrier separating Israel from the West Bank, known as the “security fence” by Israelis and the “apartheid wall” by Palestinians. At a certain point, and with no advance warning to anyone, Francis asked his driver to stop and pull over. There was a moment’s delay as his security team scrambled to get into position and then the pope got out, walked over to a portion of the wall where “Free Palestine!” had been graffitied, and paused for about five minutes of silent prayer. At the end, Francis placed his hands on the wall and leaned in until his forehead came to rest, then made the sign of the cross. It became the most powerful visual of the trip and was almost universally taken as a gesture of solidarity with Palestinian suffering.

While it was happening, a visibly flustered Vatican spokesman, an Italian Jesuit named Fr. Federico Lombardi, was madly thumbing his BlackBerry. Lombardi knew that the stop at the wall was political dynamite and was desperately trying to invent a nonpartisan way to frame it. Later that day, Lombardi told reporters that Francis wasn’t taking sides but was simply expressing a biblical lament. “The pope thinks like a prophet,” Lombardi said. “He imagines a day when a wall won’t be necessary to keep these two peoples apart. This was not a statement about the present political situation.”

In a sense, Lombardi and other Vatican officials trying to spin the stop at the wall lucked out, because two hours later the pope supplied an even more startling storyline when he announced that he had invited both Abbas and Israeli President Shimon Peres to join him for a prayer for peace “in my house.” Both leaders swiftly accepted the invitation, and the date was set for June 8.

In the run-up, the Vatican did everything it could to lower expectations. “Anybody who has even a minimum understanding of the situation would never think that as of Monday, peace will break out,” said Fr. Pierbattista Pizzaballa, a Franciscan priest based in the Middle East who organized the event. The pope’s lone ambition, he said, was to “open a path” that was previously closed.

Peres and Abbas arrived separately at the pope’s residence at the Domus Santa Marta, where each had a brief private moment with the pontiff. Francis and his guests were then joined by Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople, with TV cameras capturing the four men exchanging embraces and kisses. They proceeded to the Vatican gardens, chosen as the setting because they contain no obvious Christian symbolism, and took part in a service that featured scriptural readings and prayers for peace from Judaism, Islam and Christianity.

Francis’s message was brief but forceful. “Peacemaking calls for courage, much more so than warfare,” he said. Only the tenacious, he argued, “say yes to encounter and no to conflict; yes to negotiations and no to hostilities; yes to respect for agreements and no to acts of provocation.”

With the benefit of hindsight, the peace prayer seemed to carry three layers of significance. First, it pioneered a new channel of backdoor diplomacy under the cover of religious piety. Second, it solidified a Vatican recipe for making prayer with followers of other religions theologically acceptable. Whenever popes staged such events in the past, there was always blowback from traditionalists who grumbled that such exercises promote the idea that all religions are equal, amounting to a sort of New Age sacrilege. This time, there was no single moment of joint prayer but rather separate prayers for Jews, Muslims and Christians. Organizers insisted that the leaders were not “praying together” but instead “coming together to pray.” Third, the fact that Francis invited Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople to join the summit has ecumenical importance, because it signifies that it wasn’t just a papal undertaking but a broader Christian project. It also suggests that in the future the pope will look to build ecumenical coalitions behind his peace initiatives.

By now, Francis has demonstrated how he wants to engage the world as a peace pope. He approaches conflicts in a uniquely spiritual fashion. He wants to rely on the resources of faith—prayer and fasting, invocations of the sacred texts of the world’s great religions, and popular devotions and religious observances. In his eyes, it’s not only the appropriate way for a pope to exert his influence, it’s also good politics. Many of the world’s bloodiest conflicts have a clear religious subtext, which means that a spiritual leader can engage them in a fashion that no secular diplomat could.

The Francis brand of diplomacy is premised on personal relationships. American Catholic writer David Gibson refers to this one-on-one style as the “Francis doctrine,” citing the pope’s remarks immediately after his return from the Holy Land that peace is not mass-produced but “handcrafted” every day by individuals.

This artisanal approach runs through the pope’s peace efforts. Francis felt emboldened to invite Peres and Abbas because he had established a personal rapport with both leaders during previous encounters in the Vatican. He brought Skorka and Abboud along to the Middle East not just because they’re well-established points of reference in interfaith dialogue but because they’re old friends. He has set up Bartholomew I of Constantinople as his geopolitical partner not just because he’s a prominent Orthodox leader but because the two men clearly like and respect each other. In the future, it’s reasonable to expect that Francis will pick where to deploy his political capital in part based on where he has developed personal ties.

Excerpted from THE FRANCIS MIRACLE: Inside the Transformation of the Pope and the Church by John L. Allen Jr., published by TIME Books, an imprint of Time Home Entertainment Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com