When LIFE set out to do a four-part series on aging in America in 1959, the magazine’s agenda was abundantly clear. “The problem of old age,” the introduction read, “has never been so vast or the solutions so inadequate.” There were five times as many elderly Americans as there had been at the turn of the century, and 60 percent of them had an annual income of less than $1,000. Medicare was still two presidents away, and people who couldn’t live with their families or on their own were often sent to state institutions where, the story read, they “lie in bed or sit beside it, imprisoned by helplessness, waiting to die, yet clinging to lives of crushing emptiness.”

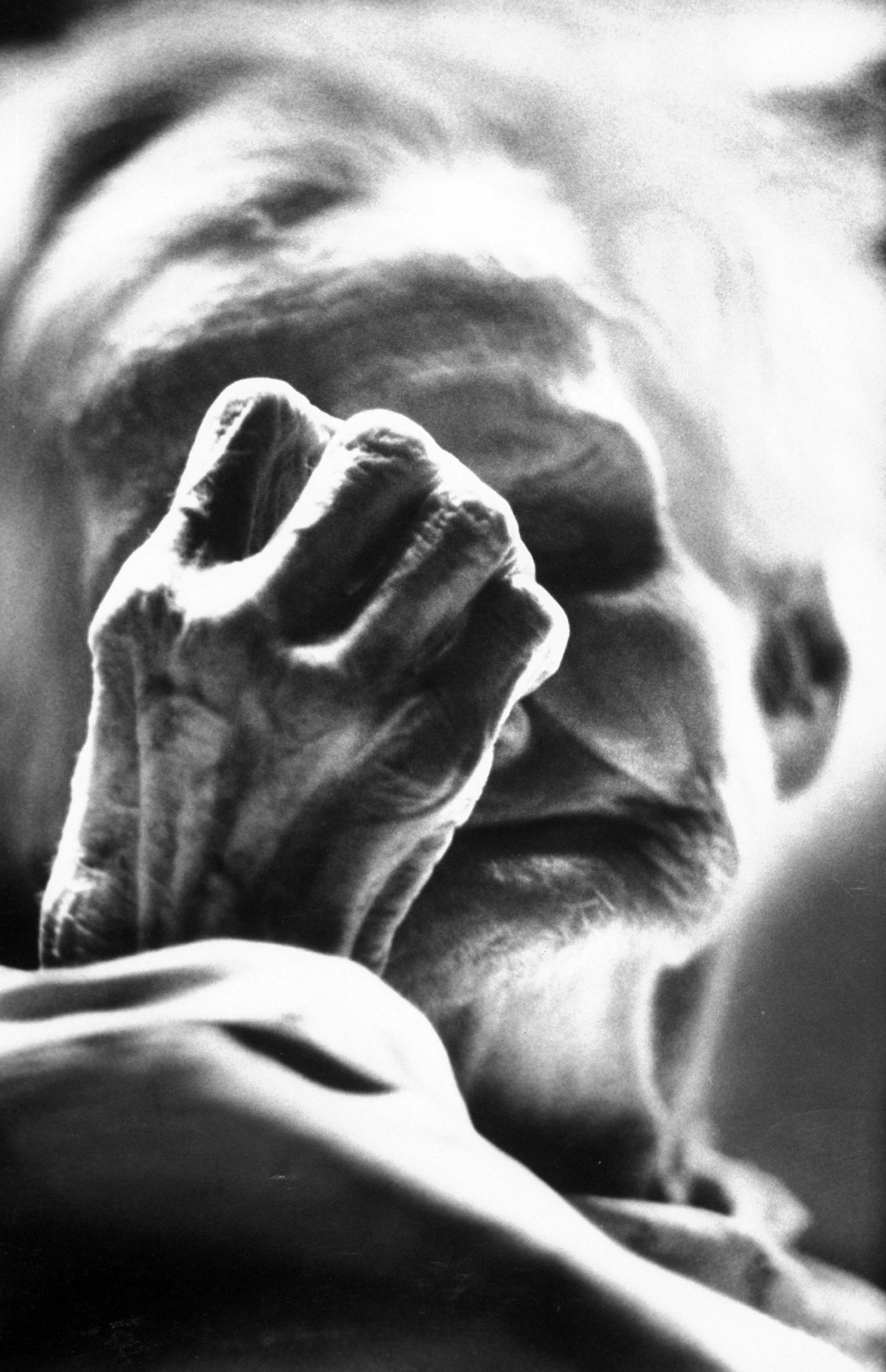

To convey the urgency of the problem to its readers, LIFE would put them face to face with it. The editors would ask them, implicitly, to picture their own mothers and grandmothers “stored away like vegetables.” Or better yet, to see their own as-yet-unwrinkled faces reflected in the faces on its pages. The photographs would have to be difficult to see.

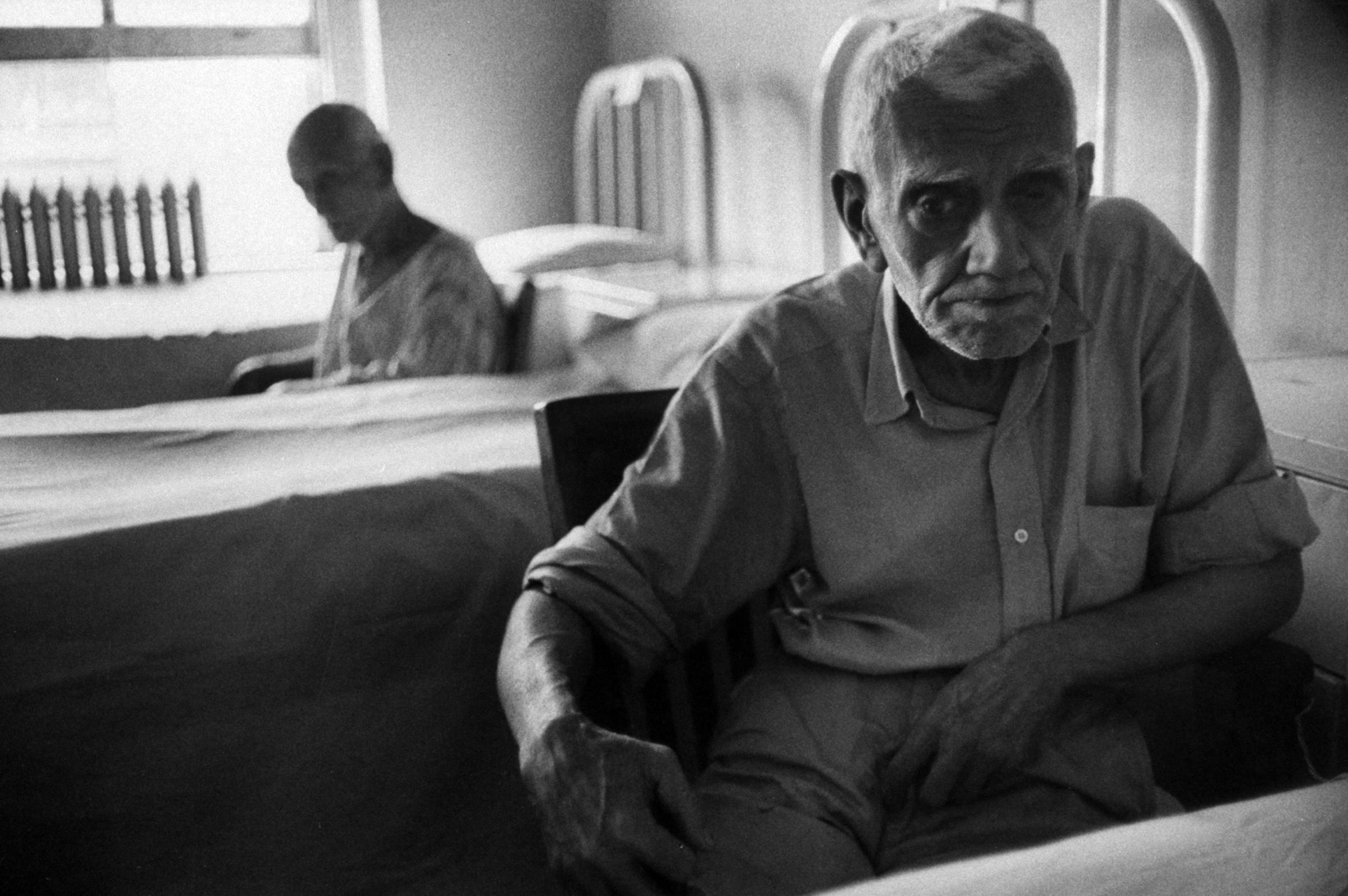

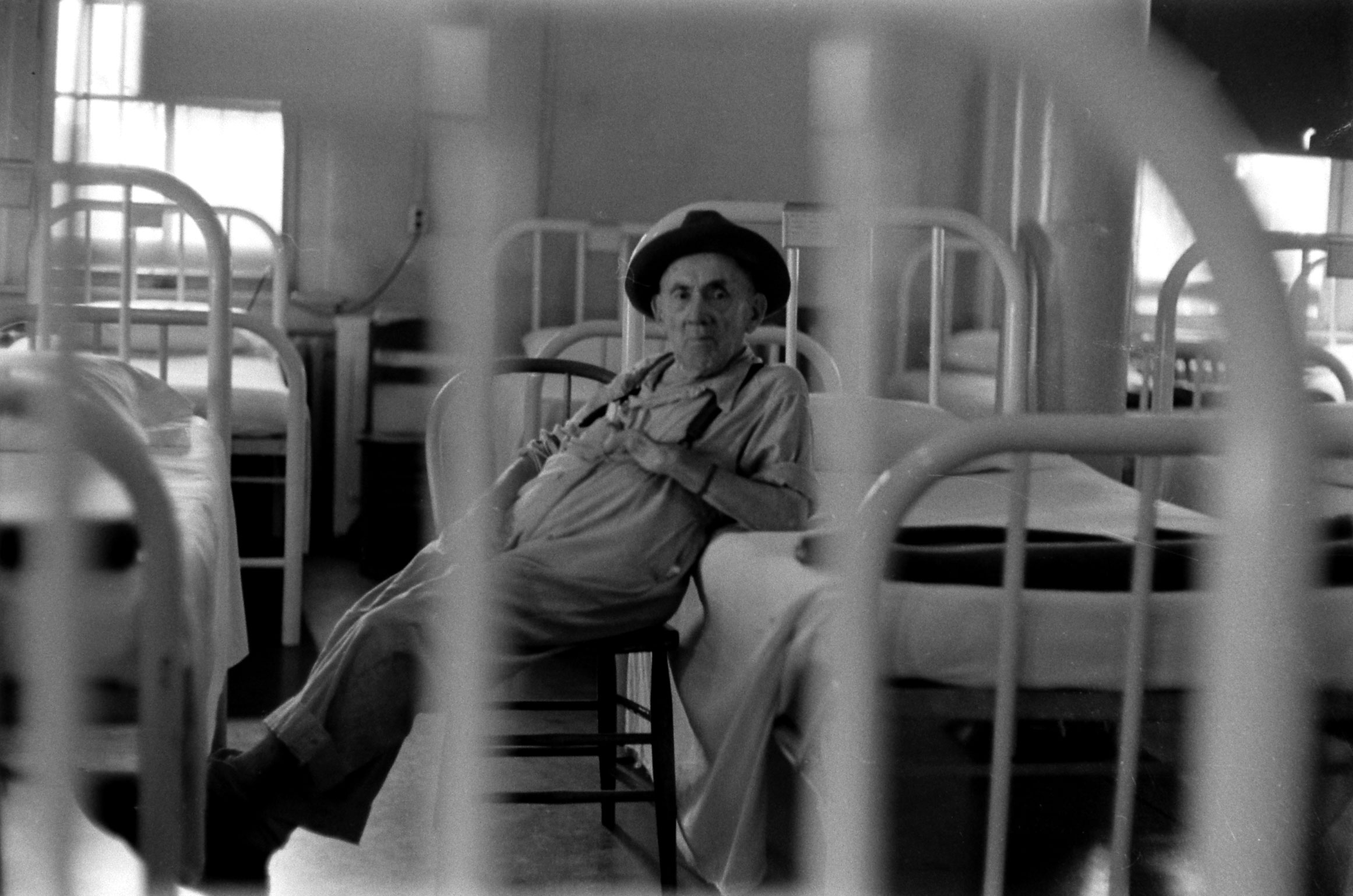

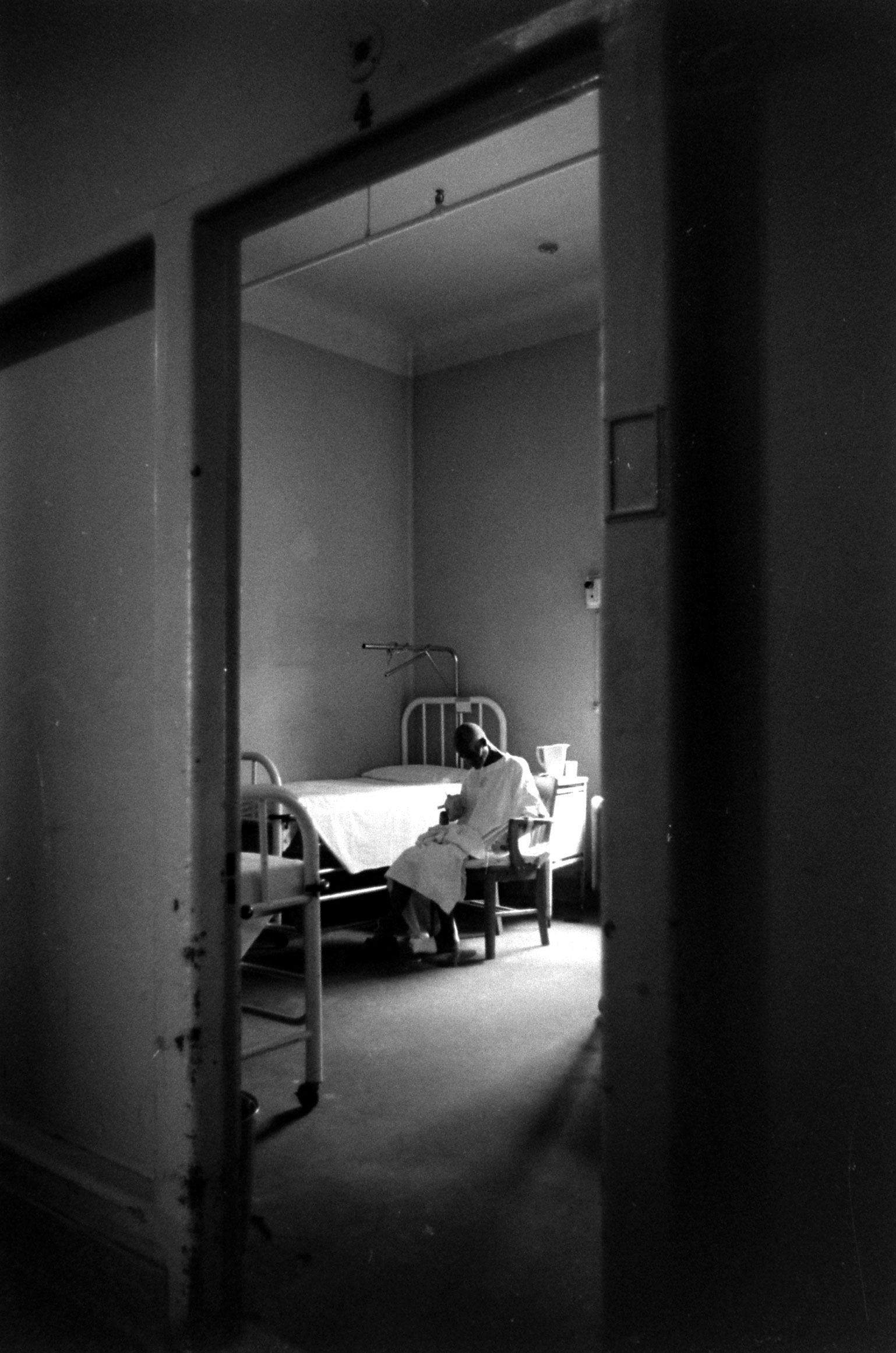

Before photographer Grey Villet was dispatched to St. Louis and Atlanta to photograph residents of state hospitals and nursing homes, his editor scoped out the locations. In a note that accompanied the rolls of film sent back to LIFE’s offices, he wrote: “Though the place is well kept and clean and the spirit of the inmates generally good, the 1911 architecture plus the general forlornness of all institutionalized old people should produce a good set of horror pictures if you want to shoot it that way.”

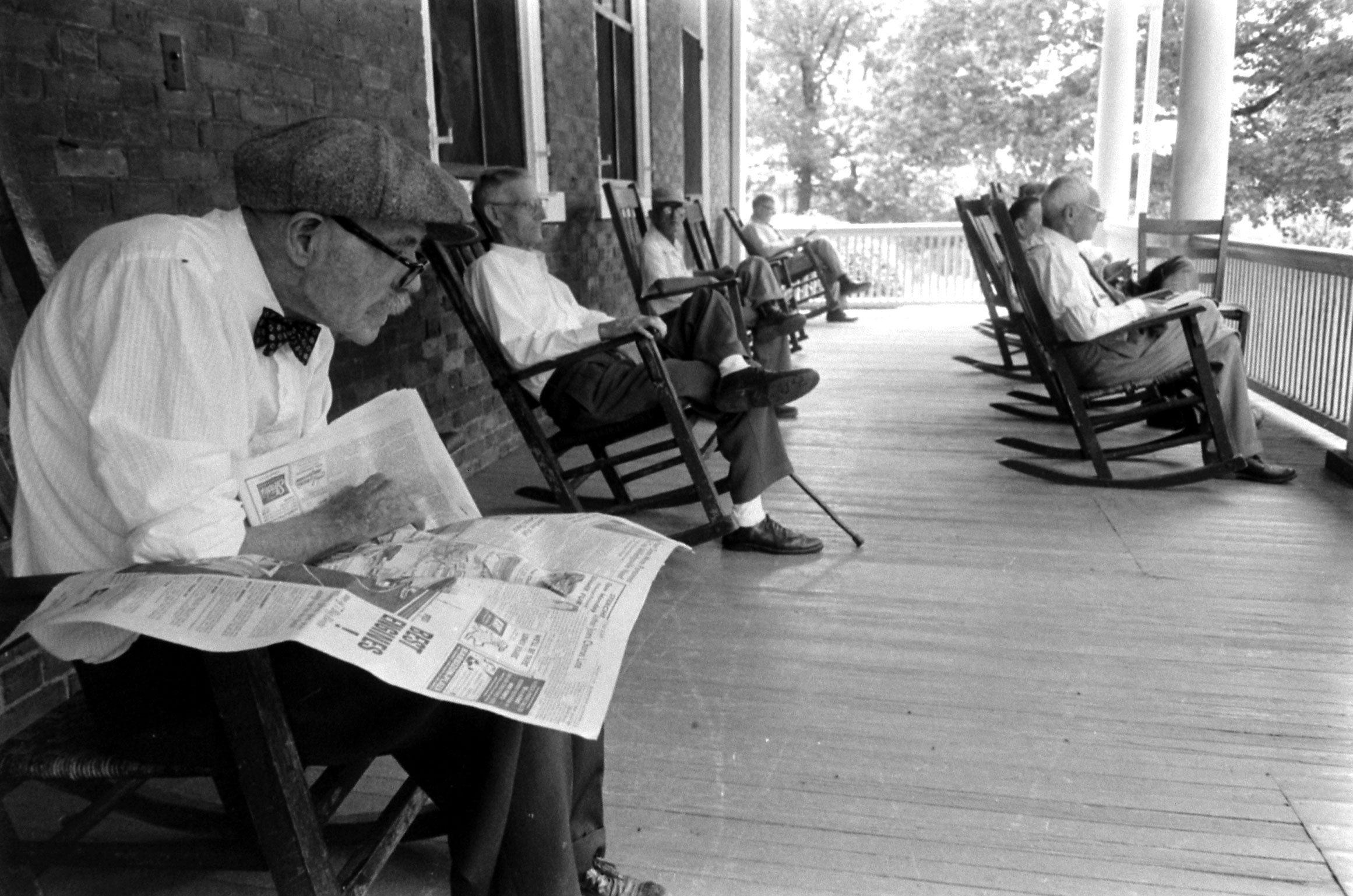

Later in the notes, the editor intentionally changed his language to “residents”—“a term preferred over ‘inmates.’” But Villet’s photos leave no doubt as to why one might compare them to prisoners. The expressions he captured are imbued with isolation and ennui, the state of being LIFE had described as “waiting to die.” His subjects seem to occupy their own civilization, separate and apart from the world that bustles outside their windows, a world that holds their past but refuses them a future.

At the St. Louis Chronic Hospital, women showed up to the dinner table two hours early and waited in silence. The editors agreed with hospital staff not to use subjects’ names, but conceded, “names would have been almost impossible to get anyway, since most of [the] people didn’t even know their names.”

Mae Rice, a nurse who ran a 16-bed nursing home in Chamblee, Georgia, was candid about the indignities her charges faced daily: “how their bladders empty unexpectedly on the floor, their gastric eruptions, their night time screams, their palsied movements.” A religious woman, she believed that if nothing else, “God has a purpose for these old people, even if it’s only to sit there on the porch and pray for their folks outside.”

If the magazine was going to take up real estate in four consecutive issues to convey the gravity of the problem, it wasn’t going to stay mum on remedies. The problem was both personal and political, and changes were desperately needed on both fronts. One installment offered examples of people who had found a reason to get up every day. Mrs. Andrew Murray Williams, 70, led tour groups on European vacations, while Dr. Robert Cushman Murray, 72, kept his job as an ornithologist at the Museum of Natural History. A doctor offered LIFE’s readers tips for preparing for their golden years: “Develop a taste for enjoying the work of others,” as you become less able to perform skills that once came easily.

The magazine outlined crucial policy changes, several of them enumerated in an op-ed by New York governor Nelson Rockefeller. The country needed to focus on rehabilitation, which pilot programs were proving could improve independence and combat feelings of helplessness. It needed affordable health insurance, quality housing and senior centers that addressed the abundant increase in leisure time post-retirement.

Perhaps more than anything, people needed something to do, some way of feeling connected to the society that too often cast them off as irrelevant. As Rockefeller wrote, “Elderly people are rich in years and potentials, each desiring to fill a useful place. They are all of us—tomorrow or the next day.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com