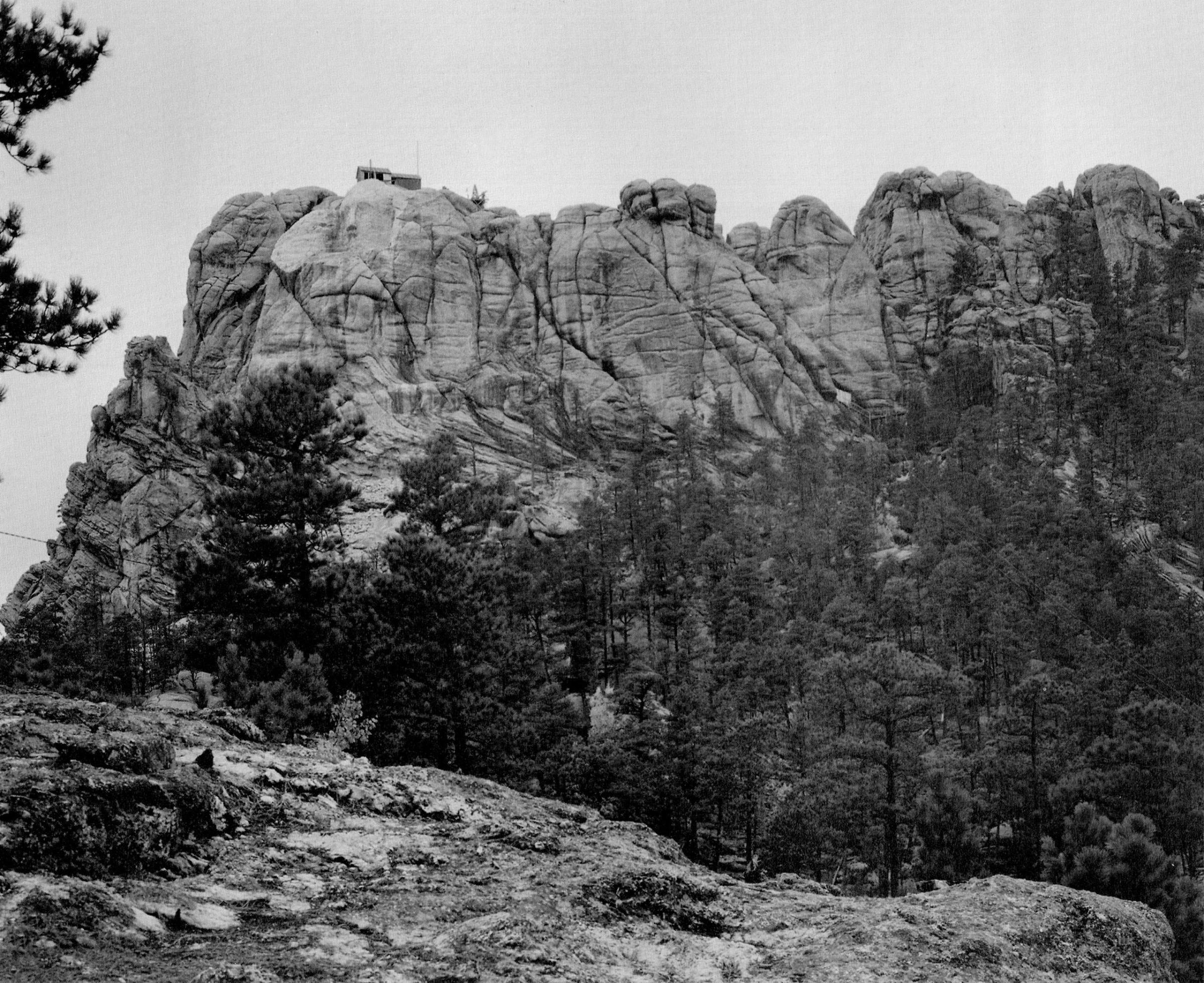

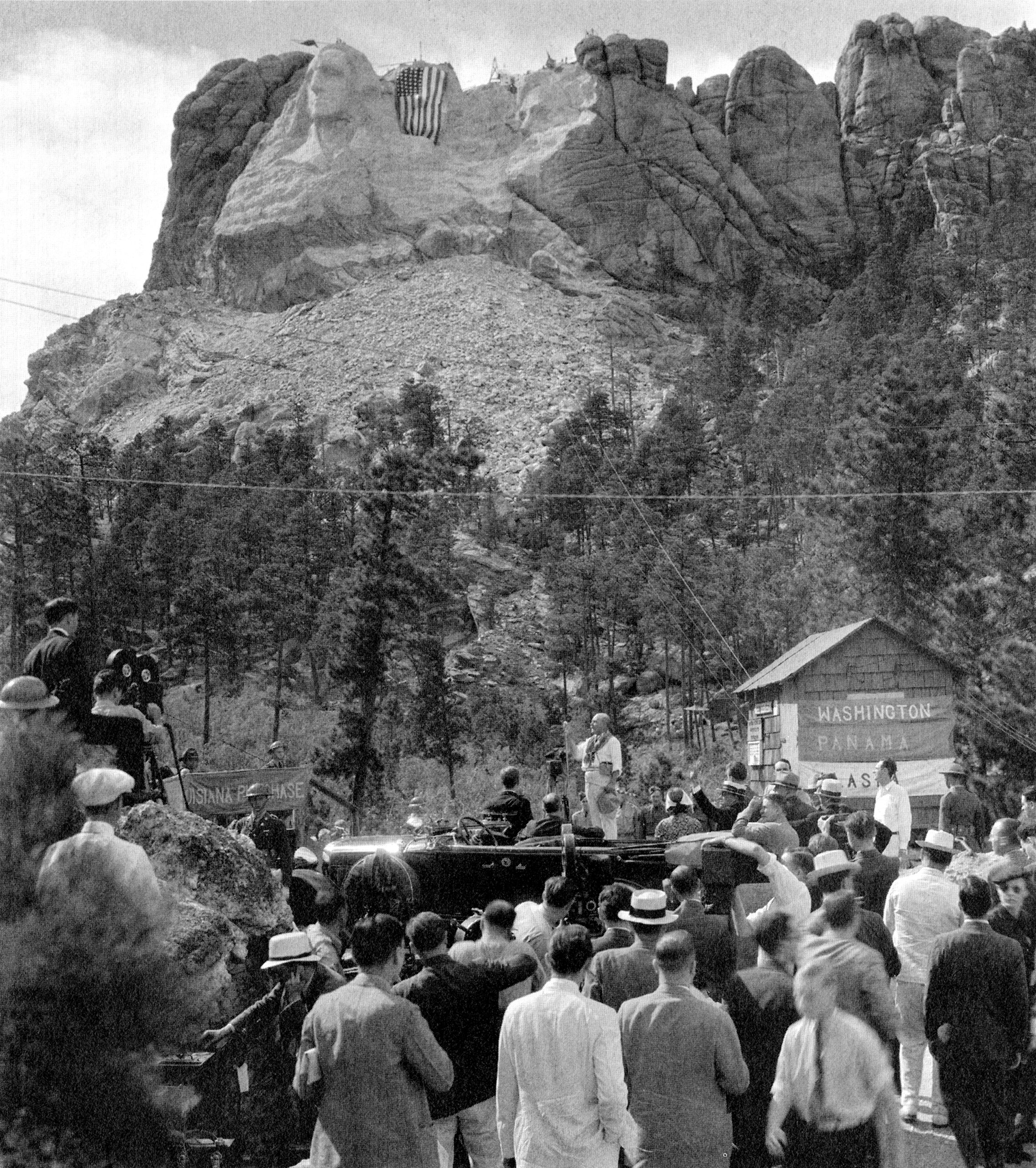

Bill Groethe was only a baby when Congress first passed legislation authorizing the establishment of a monument to “America’s founders and builders” at Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota, on Mar. 3, 1925. When the work of carving began — an event celebrated by President Coolidge, who wore a cowboy outfit to the ceremony in 1927 — Groethe was too young to care very much.

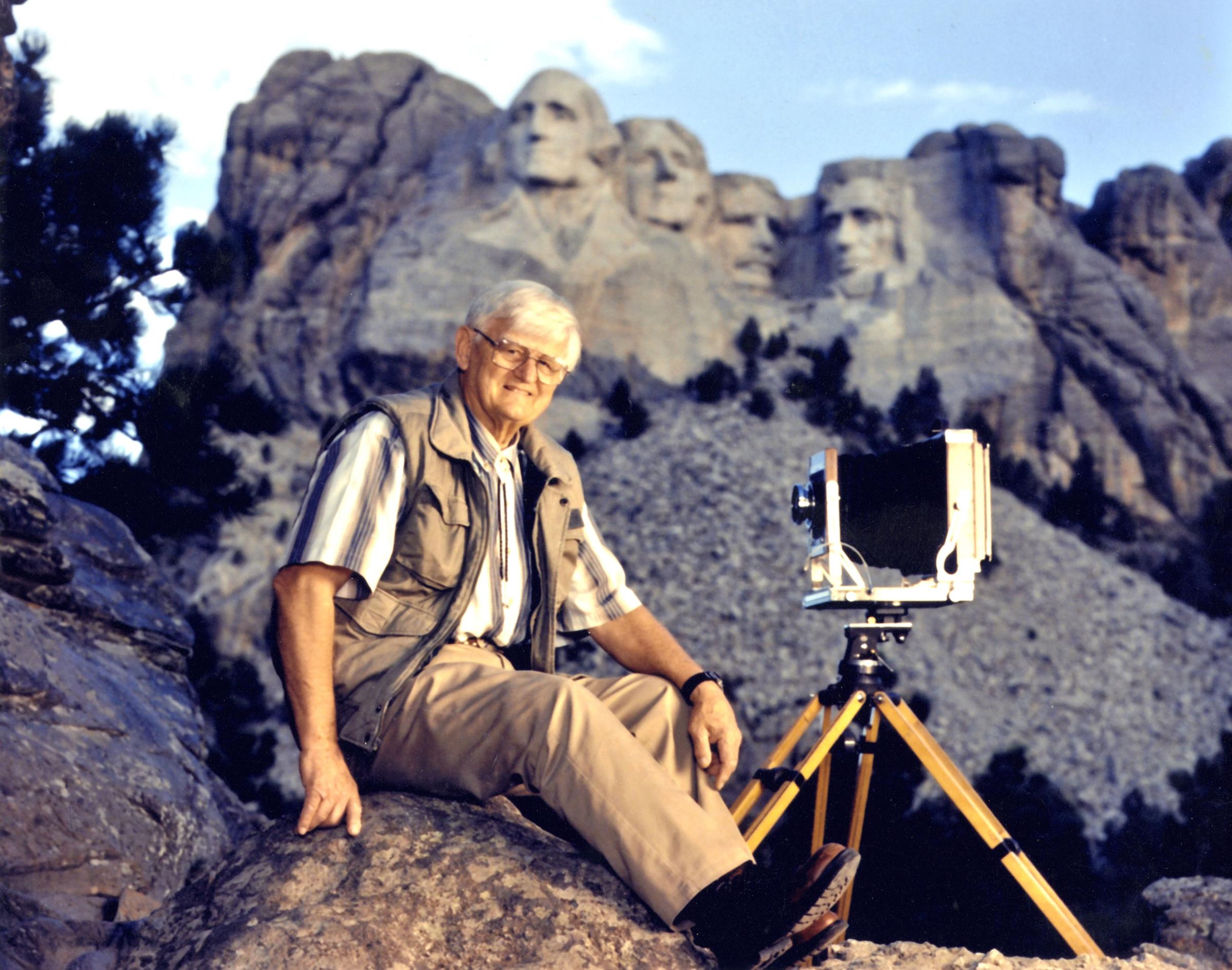

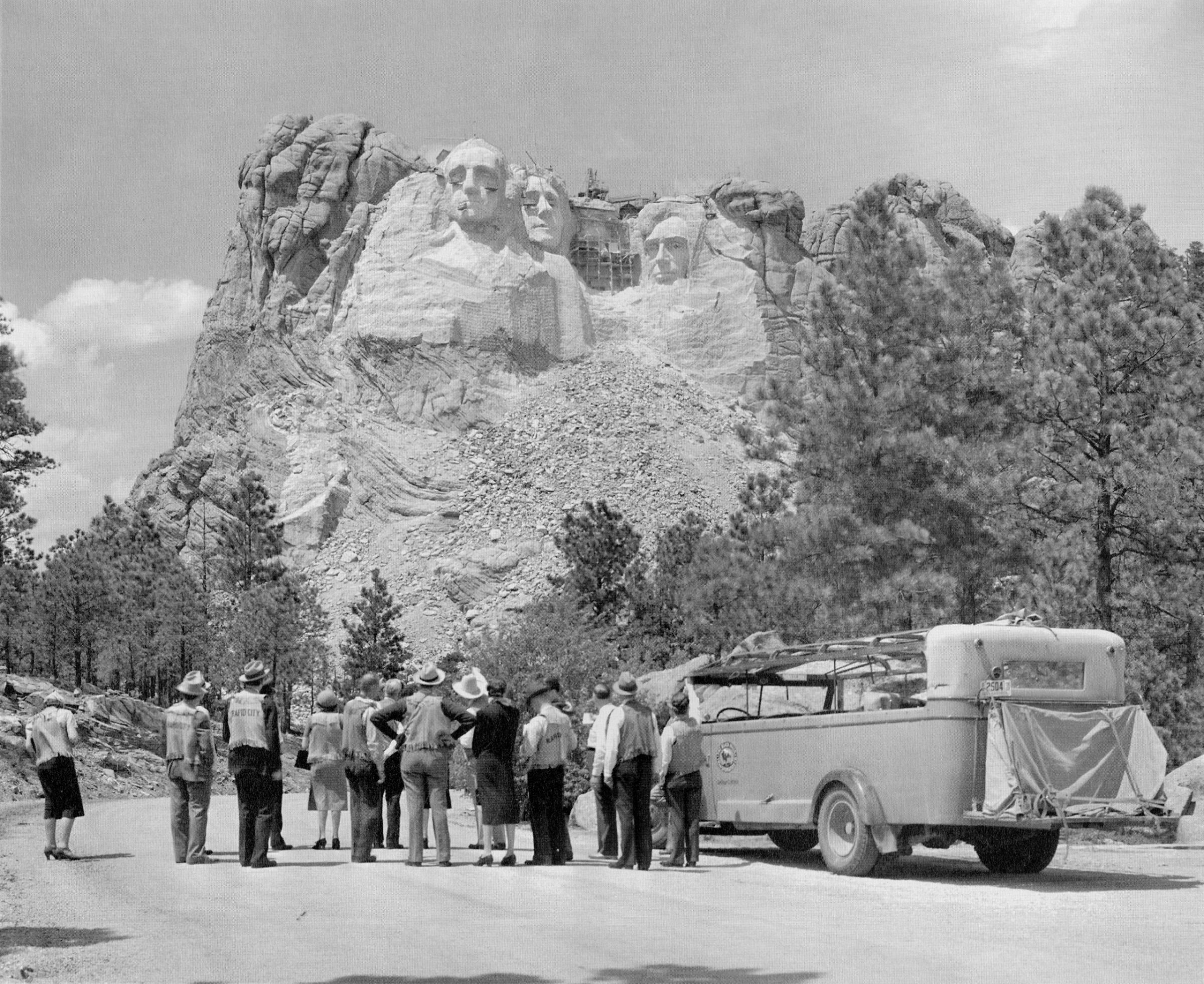

But that didn’t last long. Groethe, who is now 91, grew up and still lives and works in Rapid City, S.D.. He has seen the monument evolve over the years, and not just with his eyes: Groethe has been photographing Mount Rushmore since 1936.

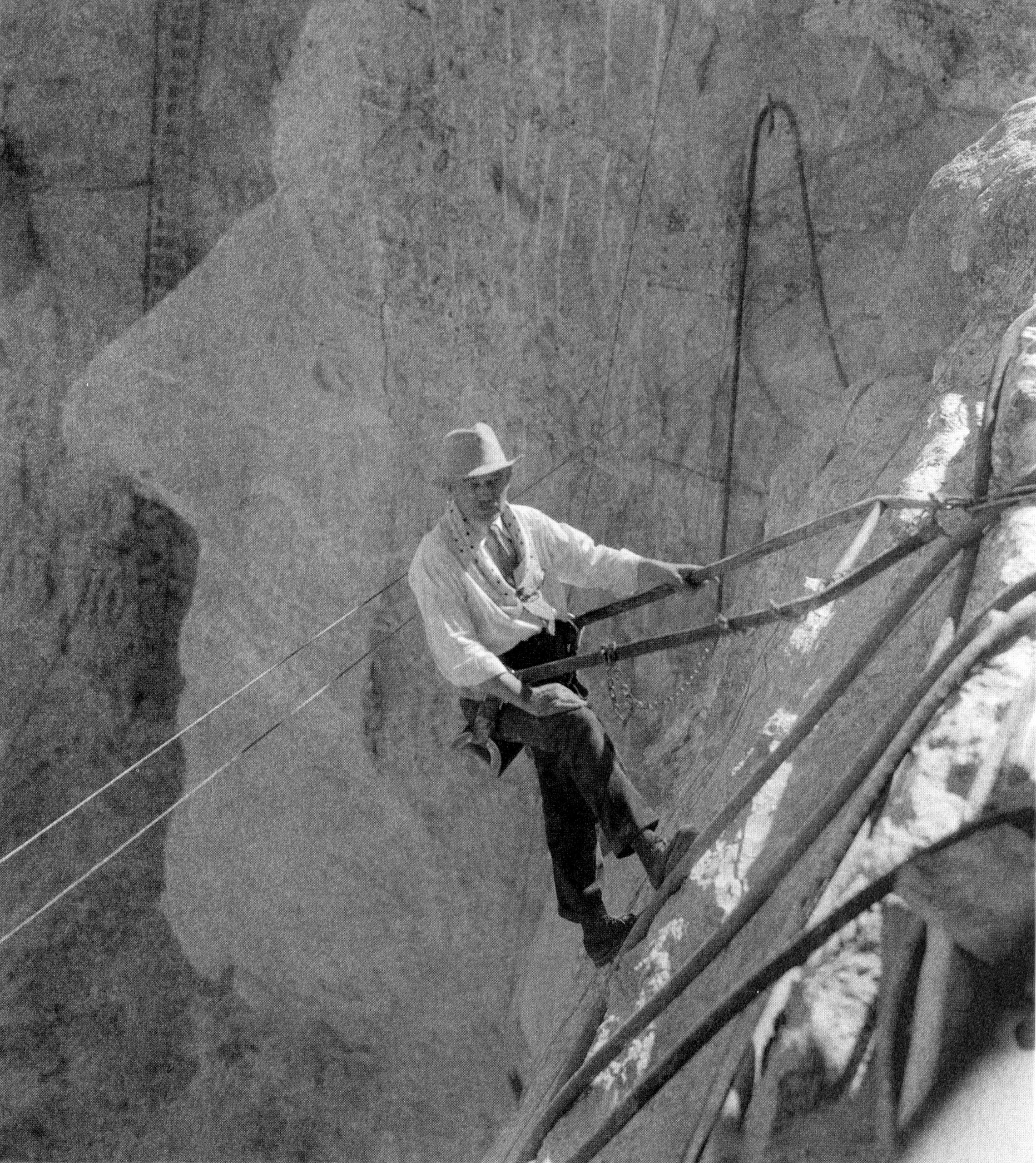

“The first time I went up to the mountain as an assistant was in 1936 when Franklin Roosevelt was here to dedicate the Jefferson figure,” Groethe tells TIME. “I carried the film bag for my boss. I was 13 years old and I have pictures of me standing by the [president’s] limousine.”

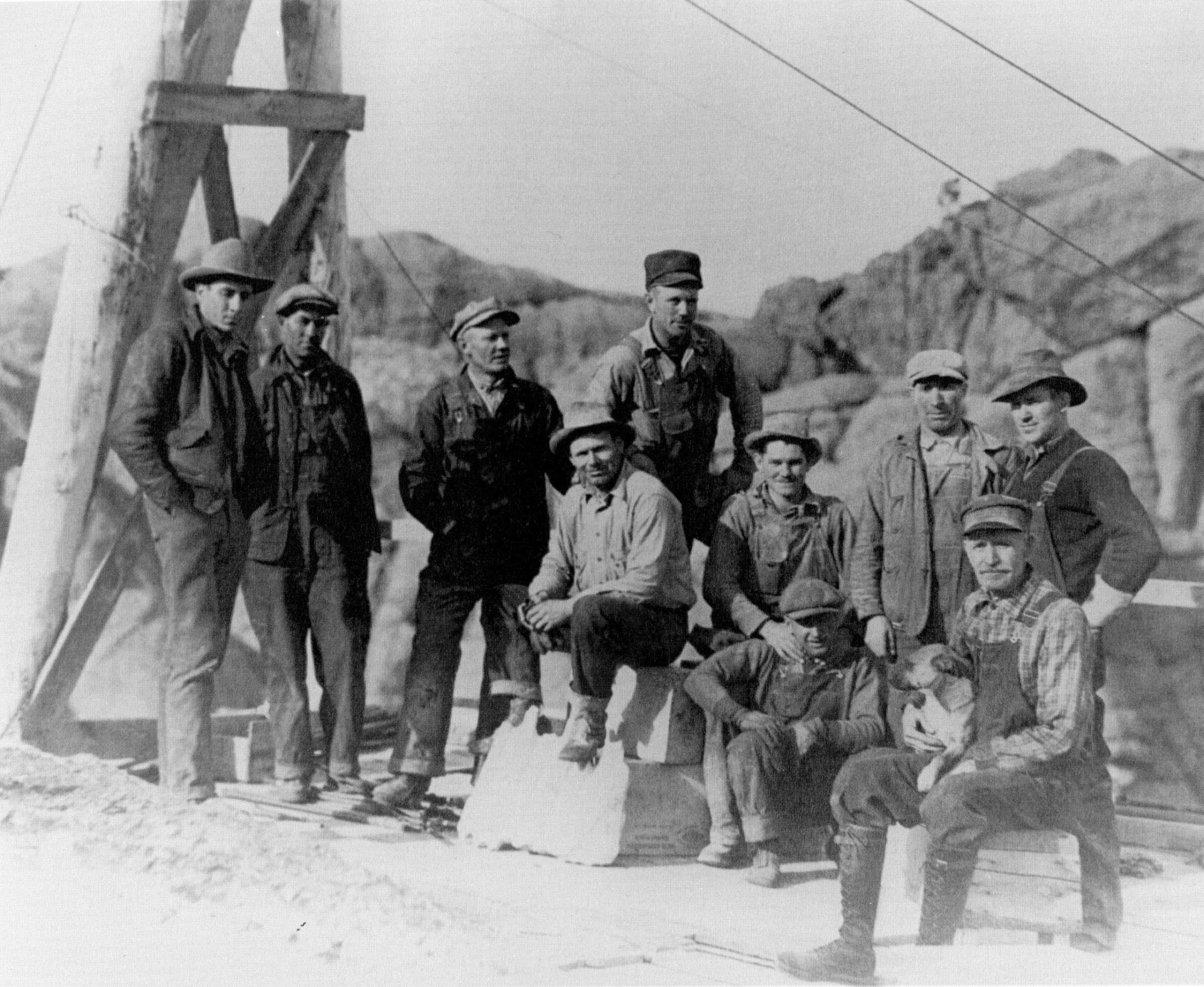

Groethe, who grew up next door to the man who owned what was then his town’s only camera shop, got his first camera at age 10 and ended up working for the photographer Bert Bell by trading his labor for photo supplies. Bell had been sent to photograph South Dakota by the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad in order to drum up interest in tourism and ended up settling in Rapid City.

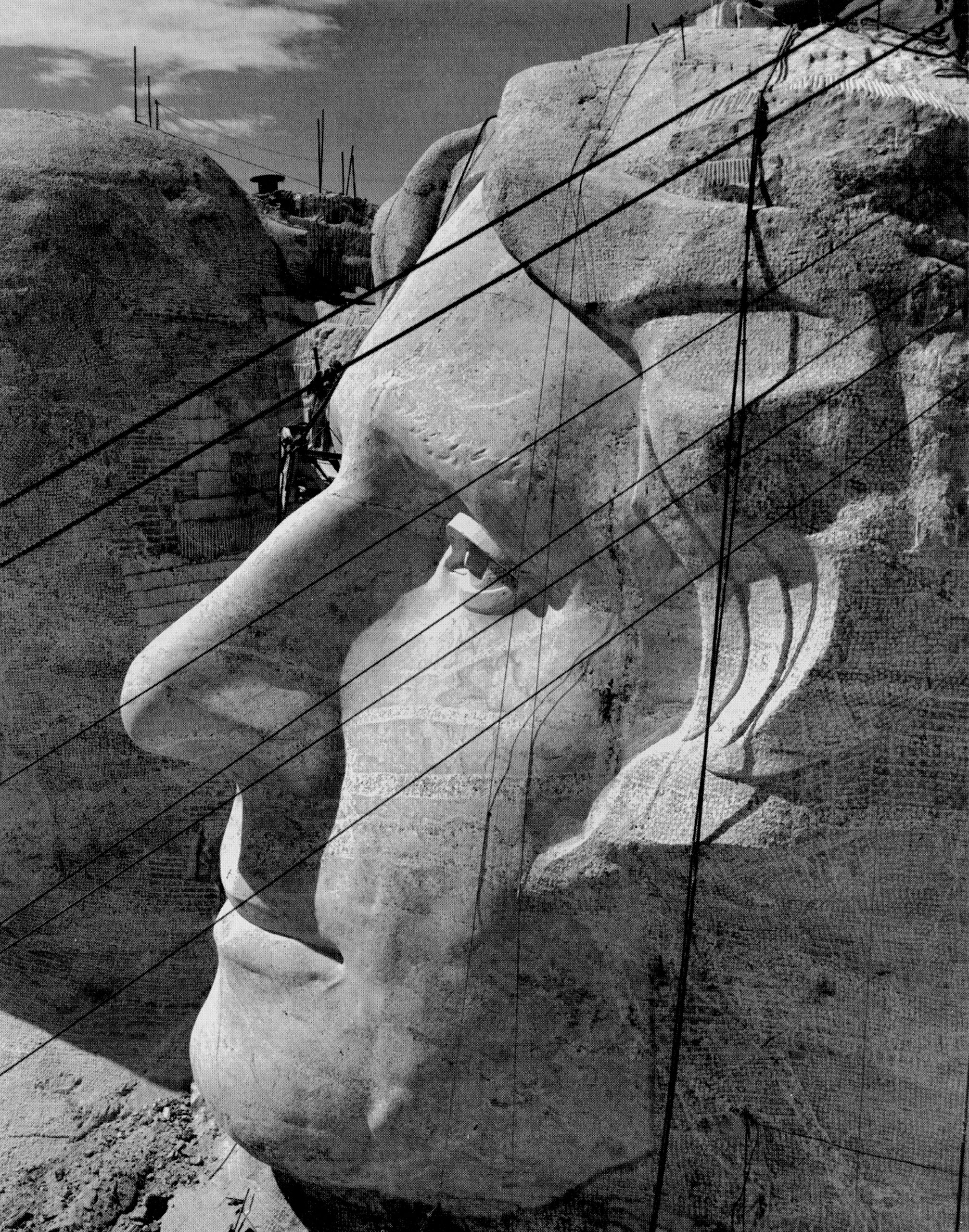

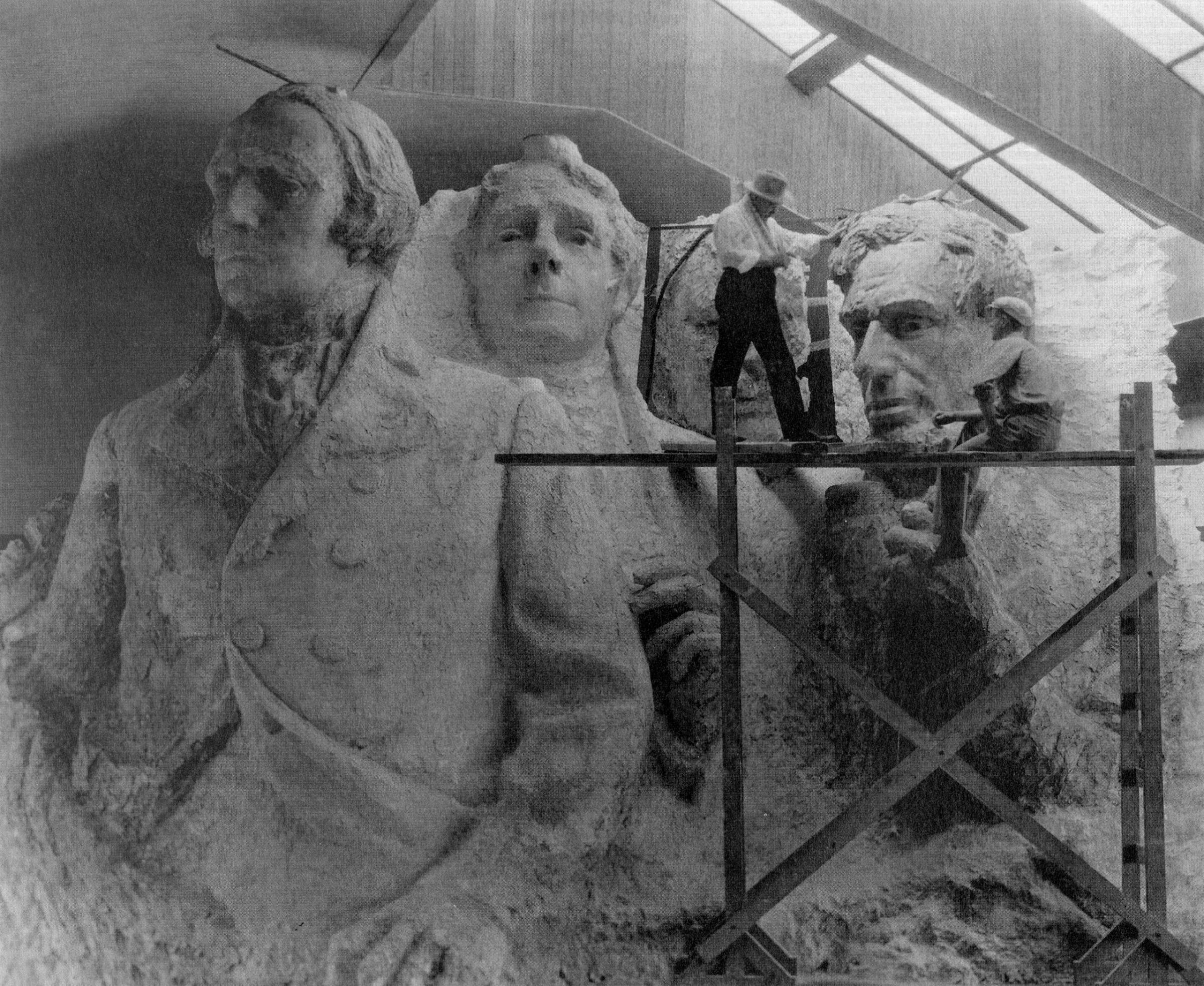

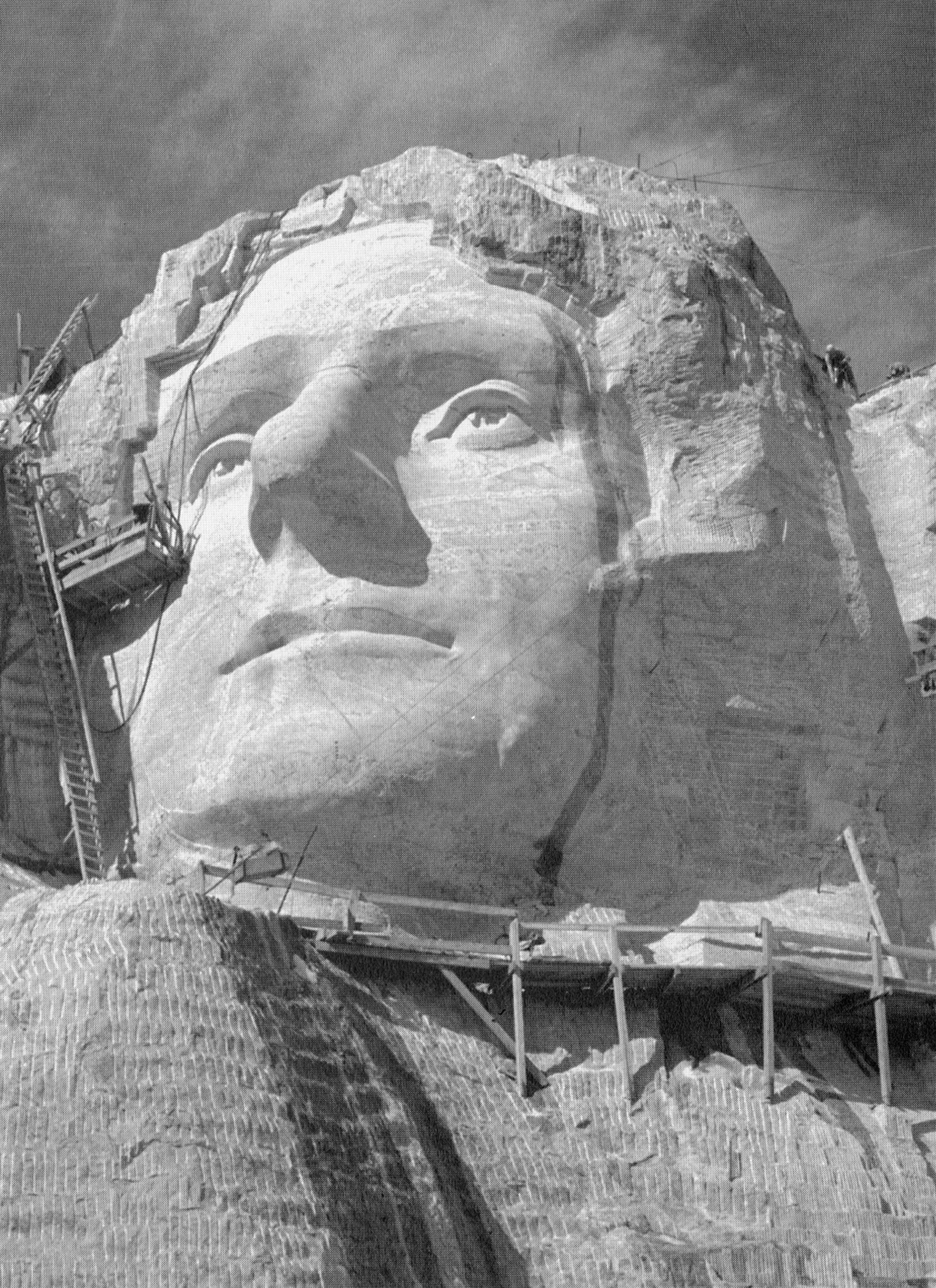

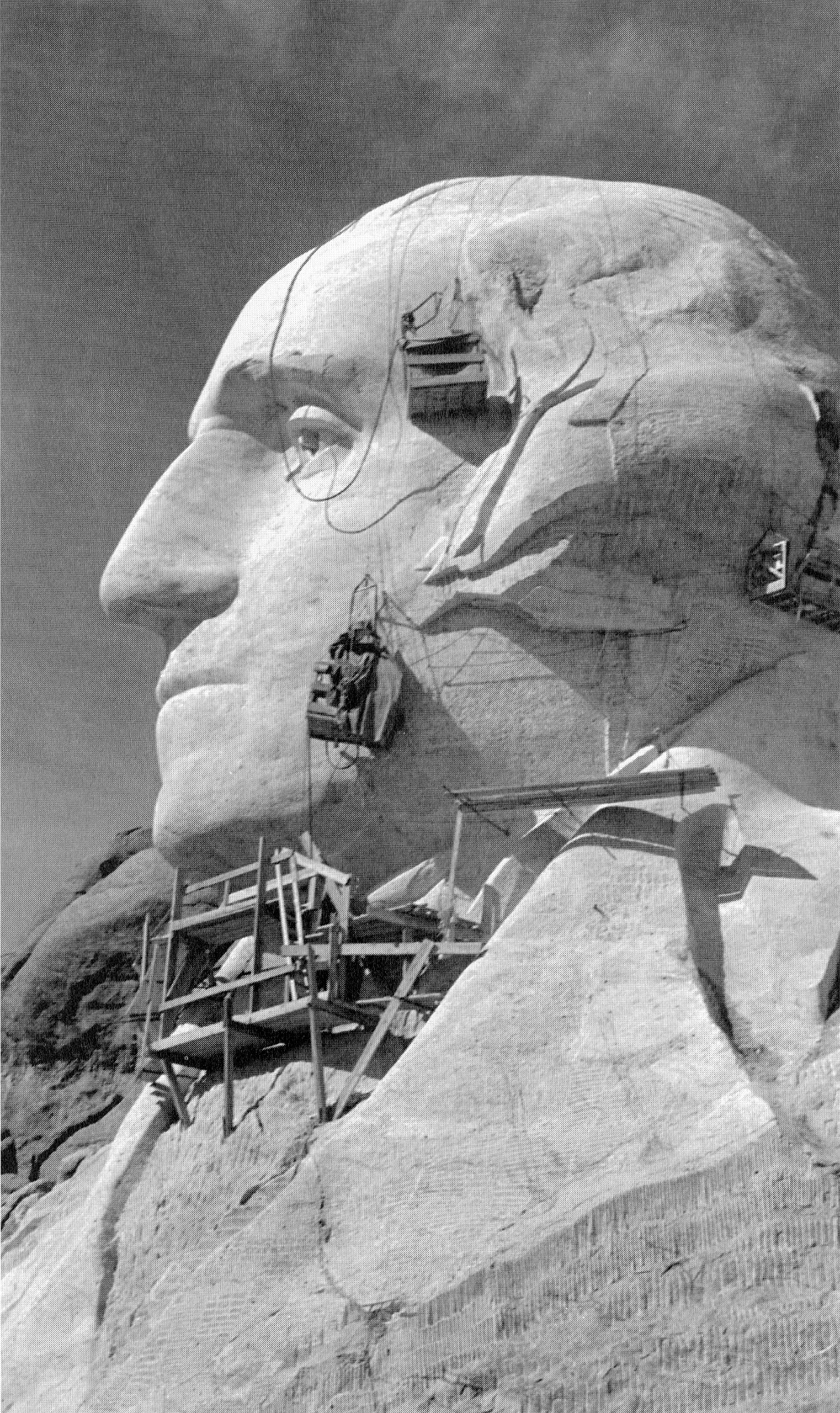

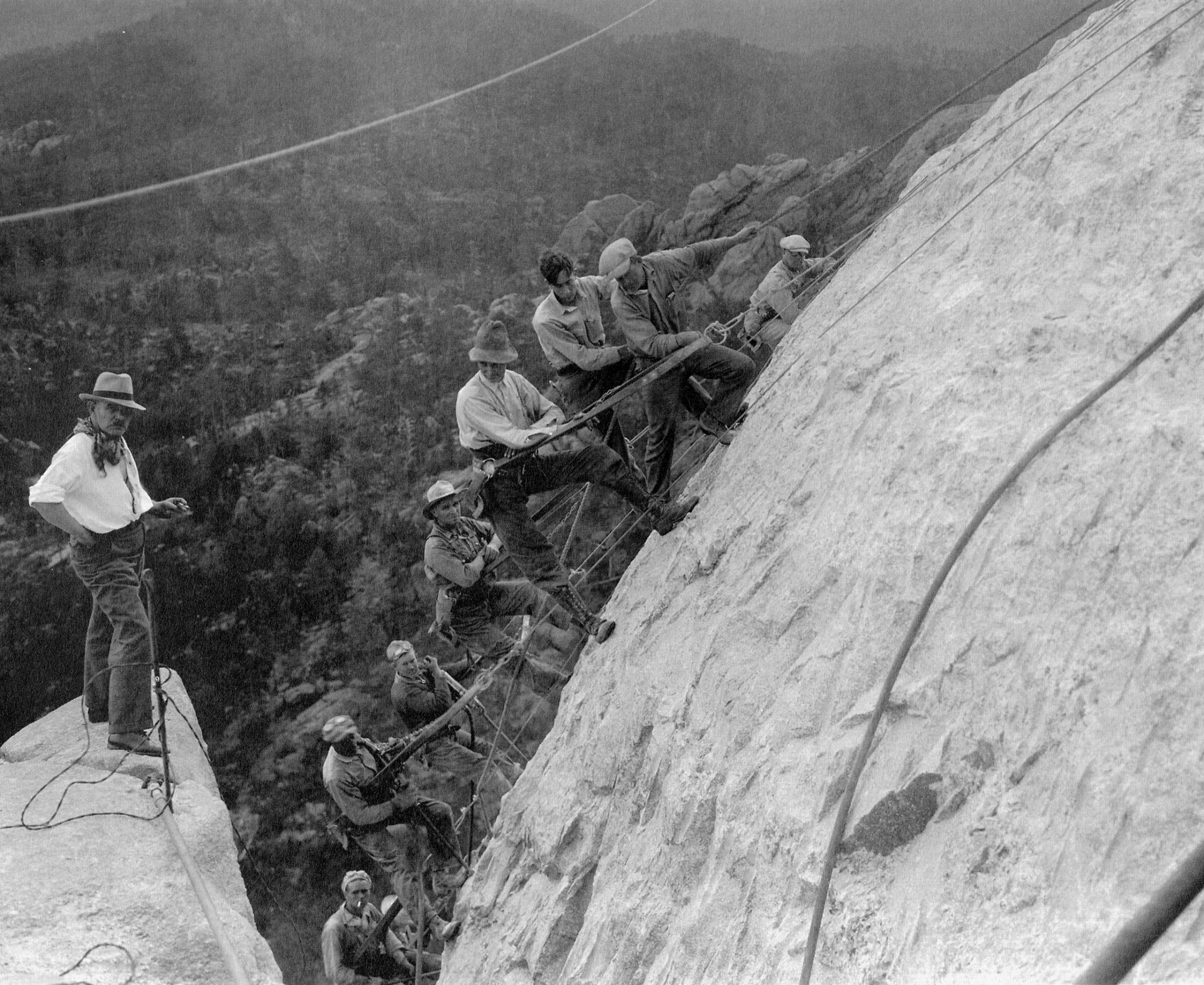

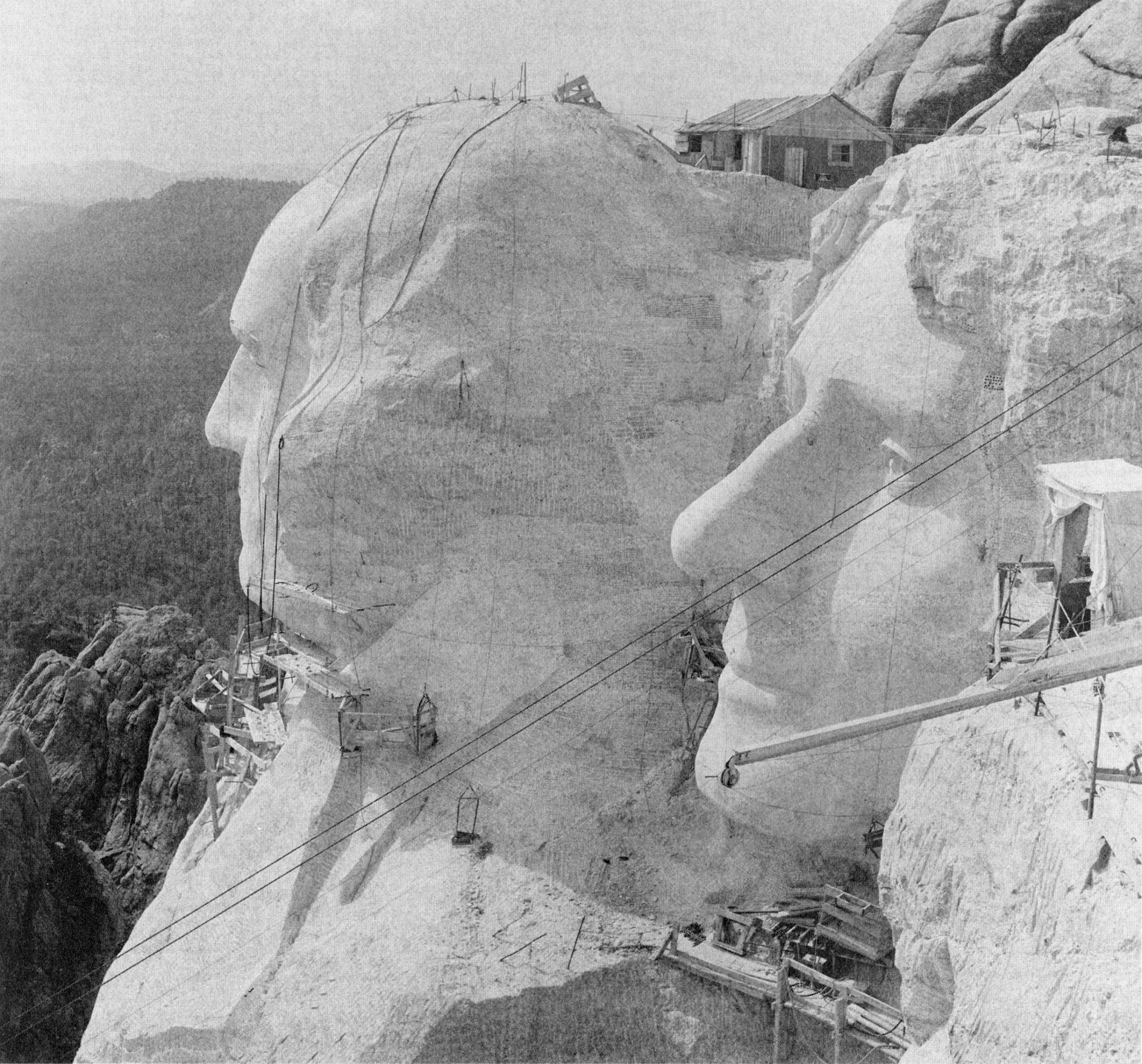

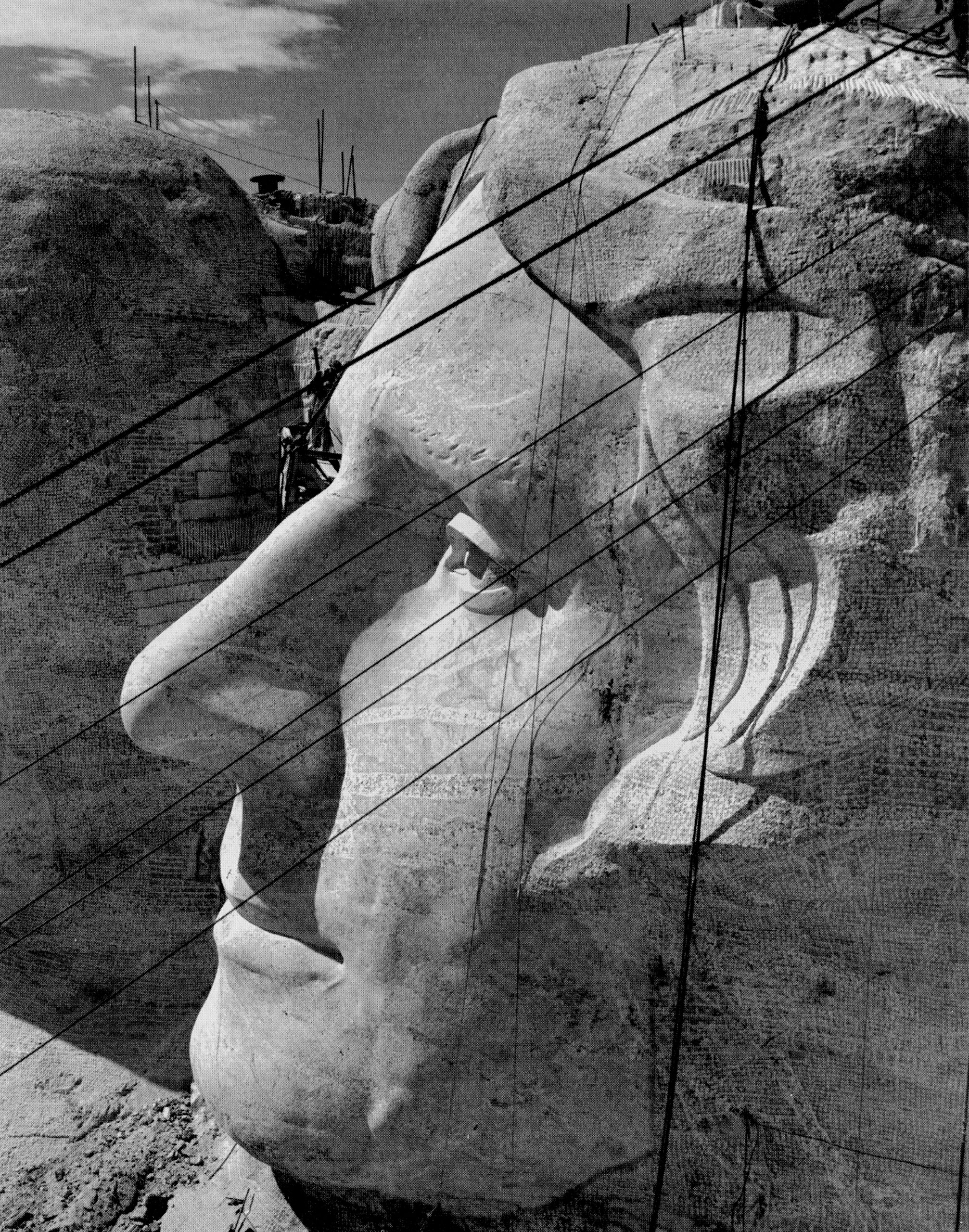

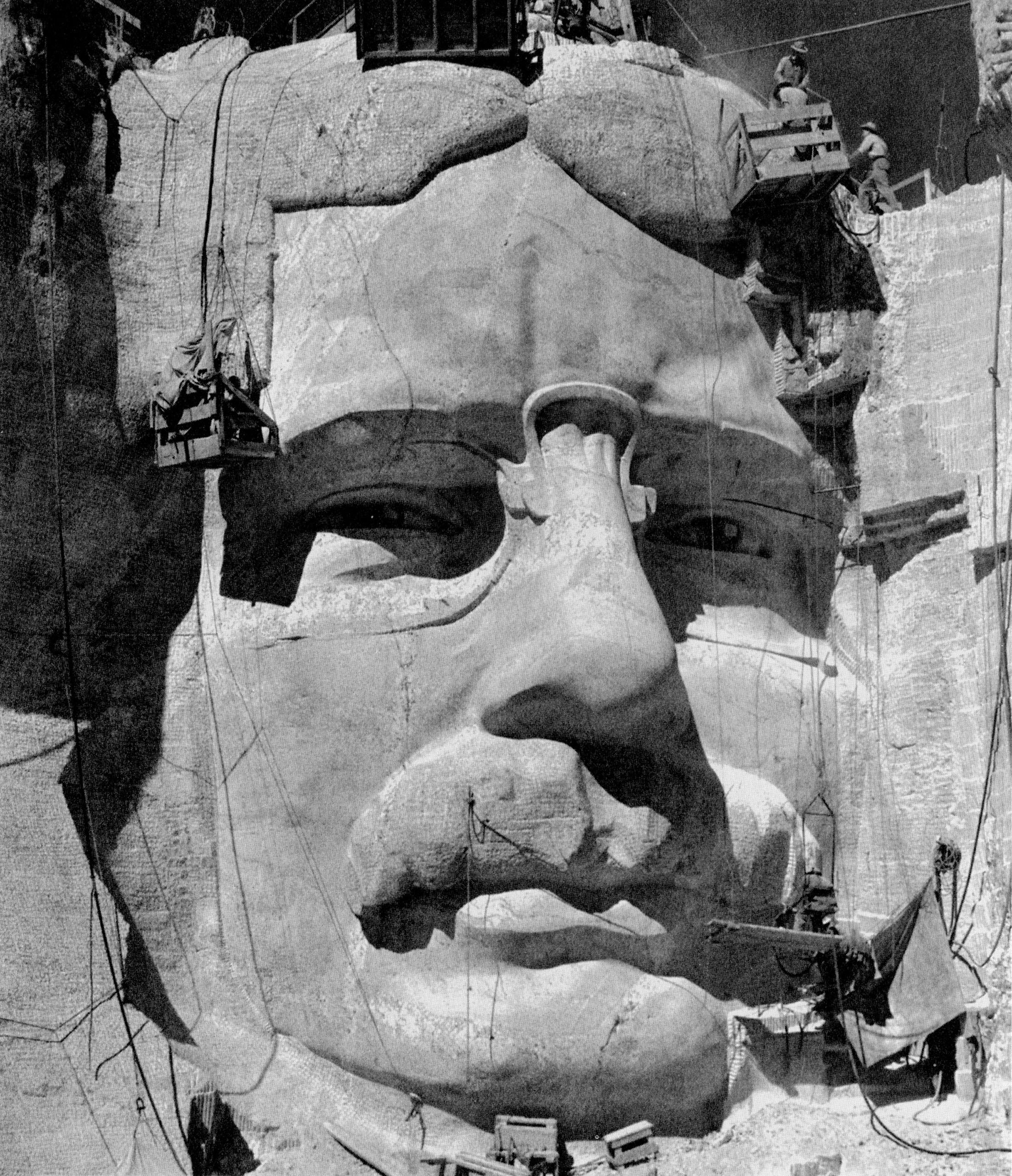

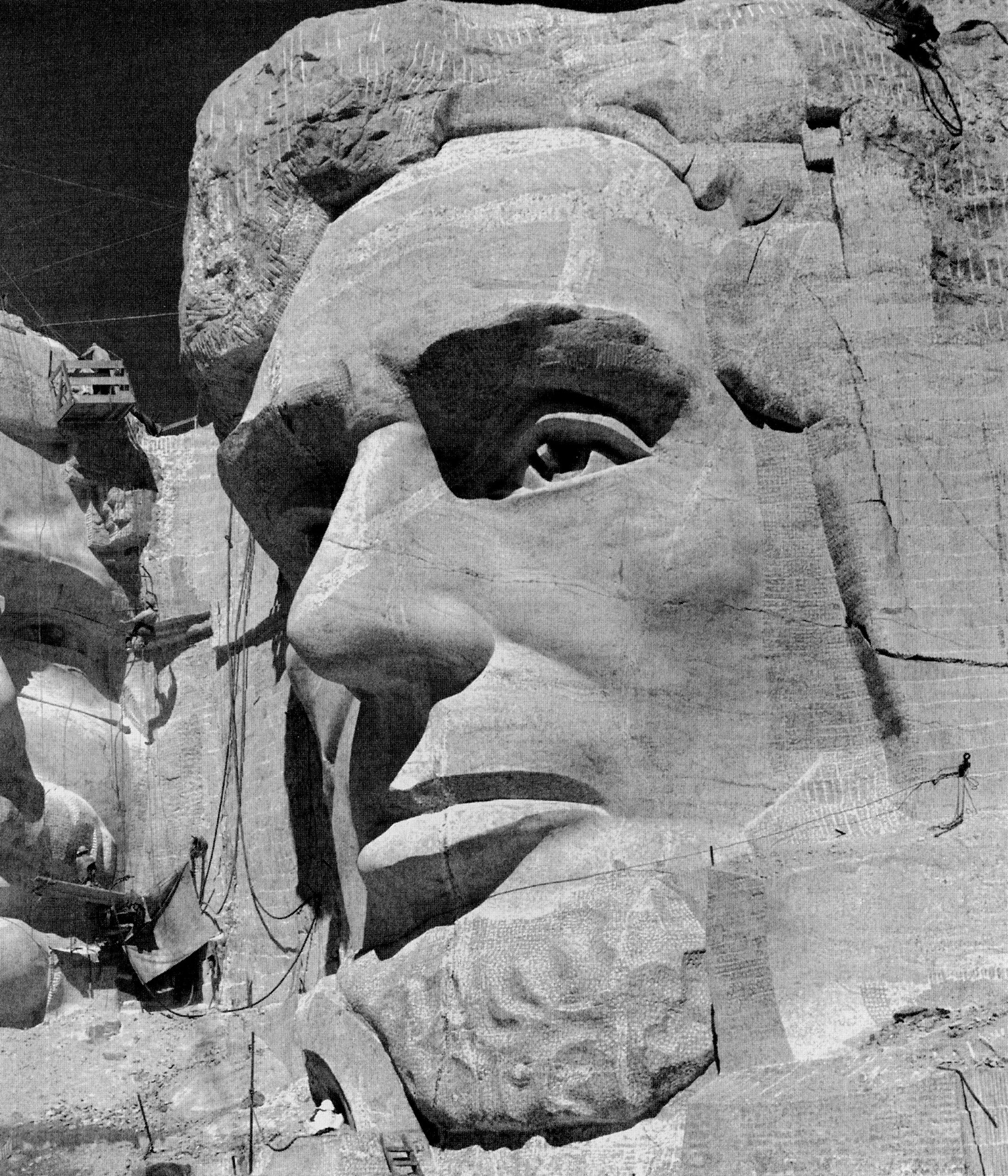

Groethe apprenticed for Bell beginning in 1935 and began to take his own photos with a folding Kodak in 1937. Groethe worked for Bell for another two decades (with the exception of three years during World War II when he was photographer for the Army Air Corps). In 1957, he opened up his own photography business. Groethe also ended up inheriting files from before his own time, of early Mount Rushmore construction; he has thousands of those negatives, from which he still makes prints.

All these years later, Roosevelt’s visit to Rapid City — the occasion for Groethe’s first trip up Mount Rushmore — ranks among his favorite memories of monument. He remembers that people came from several states nearby to attend. TIME noted the following week that the crowd nearly doubled the town’s population. “At a signal from Sculptor Borglum’s daughter, his son, across the valley, dropped the flag, revealing an heroic head of Jefferson, 60 feet from crown to chin,” the magazine reported. “Simultaneously five dynamite blasts sent rock clattering down from the space where Lincoln’s face is to be carved.”

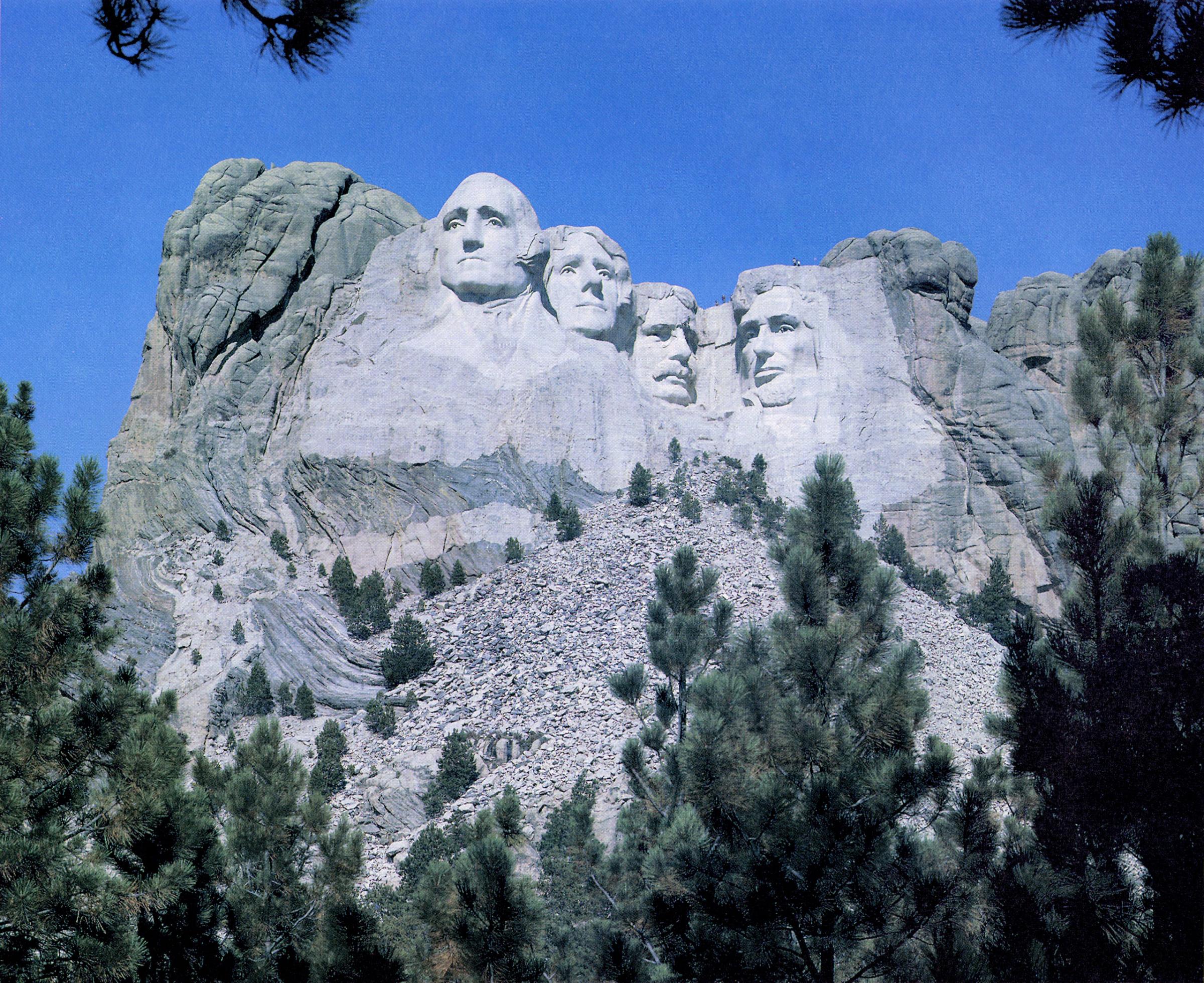

What Groethe remembers of that day is a little different, though no less exciting. “When you’re 13 years old you’re thinking mostly of being lucky to have a job and get to go along and go up in the cable car,” Groethe says. “I continue to have that interest in the mountain, of course. It means a lot to me. I still get a good thrill out of seeing the mountain. It hasn’t changed much. People change and facilities change, but the mountain stays the same.”

Mount Rushmore has not been without its detractors. The mountain is considered defaced by some, for reasons relating to the environment or Native American traditions. But Goethe says that, in his experience, the arguments against the monument don’t take away from its grandeur.

“I can attest to the fact that when I sit at a table [at Mount Rushmore], as I have for the last almost 20 years every week for a day or two in the summer, I have people from Europe and all over Asia come and tell me that all their lives they’ve wanted to come and see Mount Rushmore,” he says. “It’s an international symbol of freedom.”

Read TIME’s original story about FDR’s trip to Rapid City, here in the TIME Vault: Roosevelt & Rain

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com and Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com