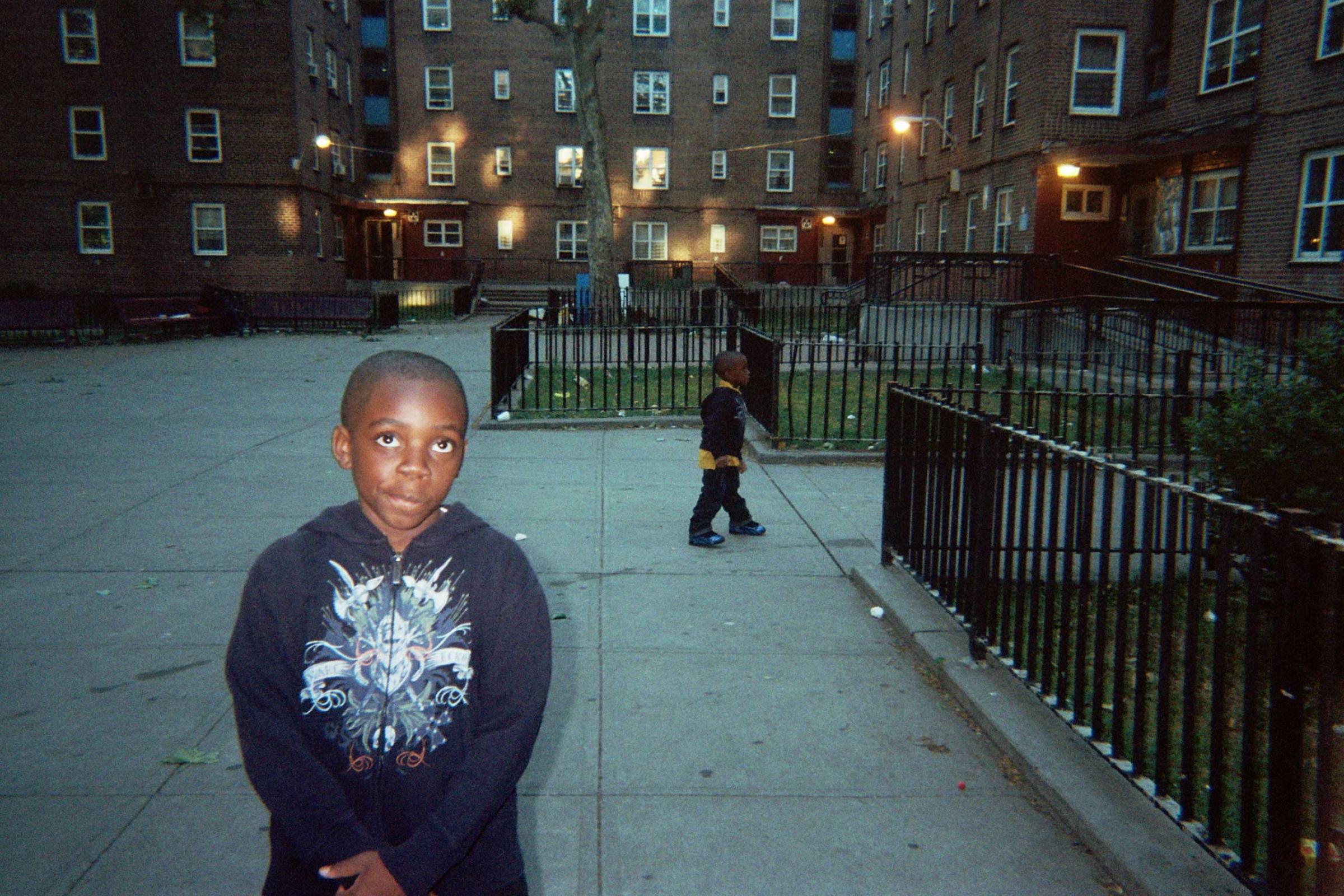

Since its initiation in 1935, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) has built hundreds of apartment blocks for hundreds of thousands of medium and low-income New Yorkers. The agency’s commitment to providing high-standard affordable housing was once widely admired and imitated around the country.

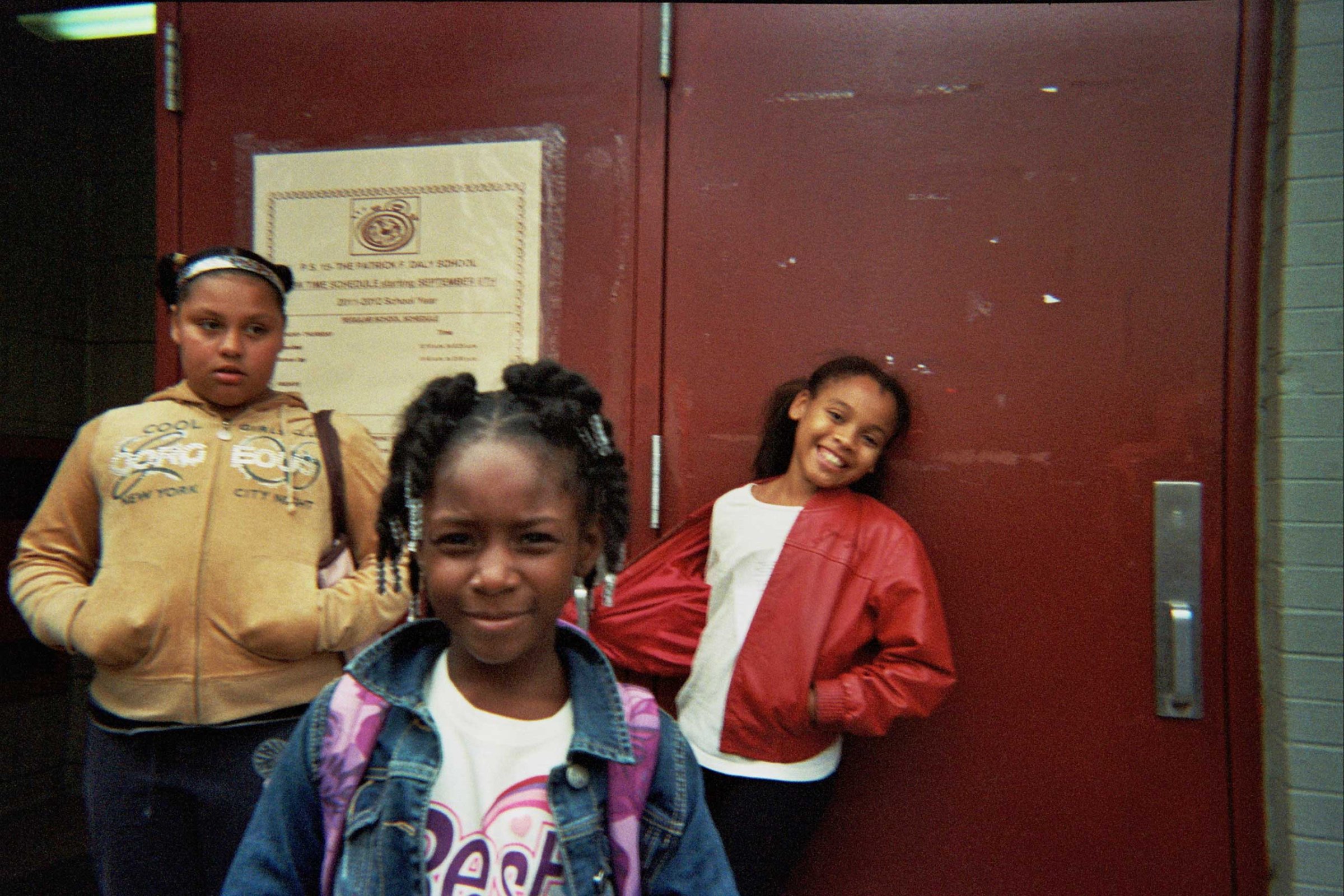

Today, these identifiable redbrick buildings have increasingly come to represent little more than physical proof of the city’s crime rates, and are regularly featured in tabloids and Hollywood films, says Jonathan Fisher, the editor of Project Lives, a photography book on life in public housing seen through the eyes of its inhabitants.

The perpetually biased presentations in the media, Fisher believes, end up doing more harm than good for the already disadvantaged residents. “Every image you saw in the media — they were either perpetrators or victims,” Fisher tells TIME. “There were just no good stories.”

Fisher first became intrigued by the concept in 2010, through conversations with his friend George Carrano, a former Metropolitan Transportation Authority official who has taken to photography in retirement. Together with photographer and educator Chelsea Davis, the three introduced the notion of “participatory photography” to the housing projects, aiming to change the negative perceptions of their living conditions and culture.

“The idea that you can give cameras, equipment and training to people who are marginalized in society and empower them to take their own portraits, find their own narratives, that just seems to be so appealing to us,” Fisher says.

The program offered a 12-week workshop to residents, most of whom are children and seniors. Once a week, Davis, previously the director of another participatory photo project at St. Louis Children’s Hospital for children struggling with cancer, invited residents into the world of photography with an education on inspirational photographers and photo techniques. After each class, she equipped her students with single-usage film cameras and sent them out to “take pictures of your life and of things that are important to you.”

The pictures residents brought back surprised them.

“[We] felt we might get back pictures of the broken toilets that hadn’t flushed in two years, and the crime chalk marks on the sidewalk, all kinds of other horrifying images, but we got none of that. We didn’t edit that out,” Fisher says. “All we got was these wonderful pictures of [people] celebrating their lives.”

Jared Wellington, 14, a former resident of the Red Hook housing project in Brooklyn, New York, participated in the program two years ago, during which he turned his lens onto his everyday life. “I try to find myself in my photos,” he explains. “I try to show how I see my friends, family and neighbors.”

“He just carried the camera like it was part of him,” his mother Celia tells TIME. And while the family cannot afford a camera, Wellington keeps making pictures using his mother’s cell phone and is inspired to continue studying photography.

Project Lives, published by powerHouse Books, is available here.

Ye Ming is a contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com