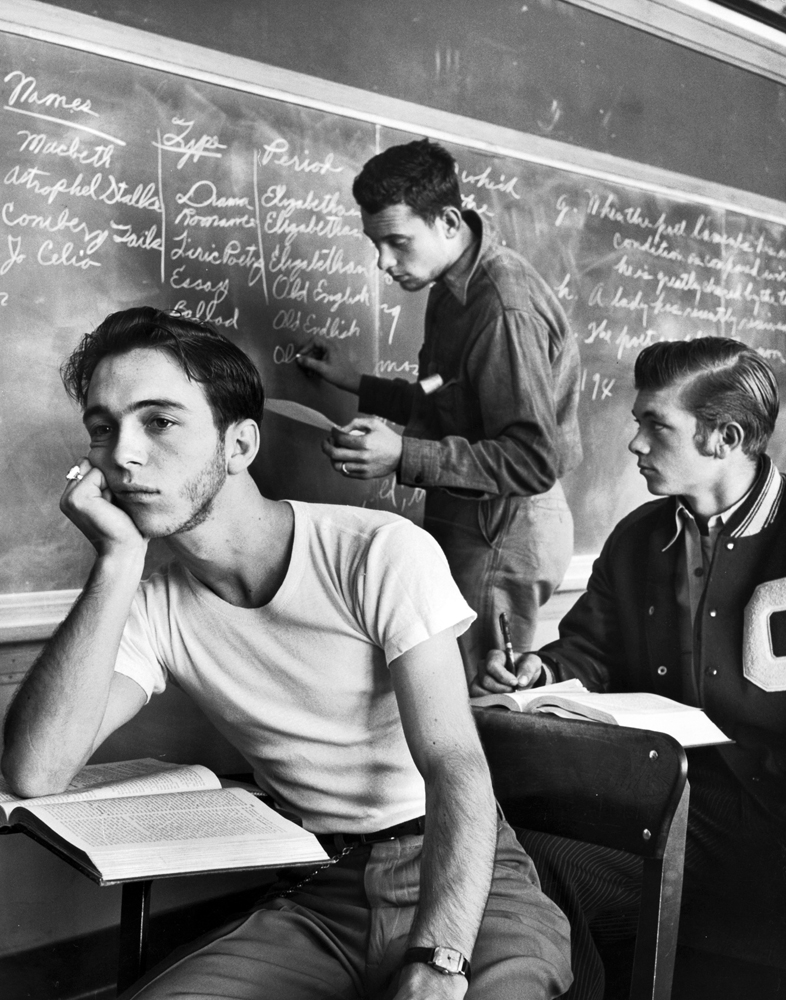

In classrooms across the country, the countdown to summer vacation has begun. The winter doldrums have always taken a toll, but in the era of test-dominated schooling and the controversial Common Core, it seems increasingly that it’s not until summer that teenagers have any prospect for having fun any more.

One of the casualties of current education reform efforts has been the erosion of play, creativity, and joy from teenagers’ classrooms and lives, with devastating effects. Researchers have documented a rise in mental health problems—such as anxiety and depression—among young people that has paralleled a decline in children’s opportunities to play. And while play has gotten deserved press in recent months for its role in fostering crucial social-emotional and cognitive skills and cultivating creativity and imagination in the early childhood years, a critical group has been largely left out of these important conversations. Adolescents, too—not to mention adults, as shown through Google’s efforts —need time to play, and they need time to play in school.

Early childhood educators have known about and capitalized on the learning and developmental benefits of play for ages. My five-year-old daughter has daily opportunities to play dress-up in her preschool classroom, transforming into a stethoscope-wearing fairy princess and tending to the imaginary creatures in her care. Her work during “center time” has all the hallmarks of what experts like psychologists David Elkind and Peter Gray define as play: she has choice in her pursuits, she self-directs her learning and exploration, she engages in imaginative creation, and she does all these things in a non-stressed state of interest and joy.

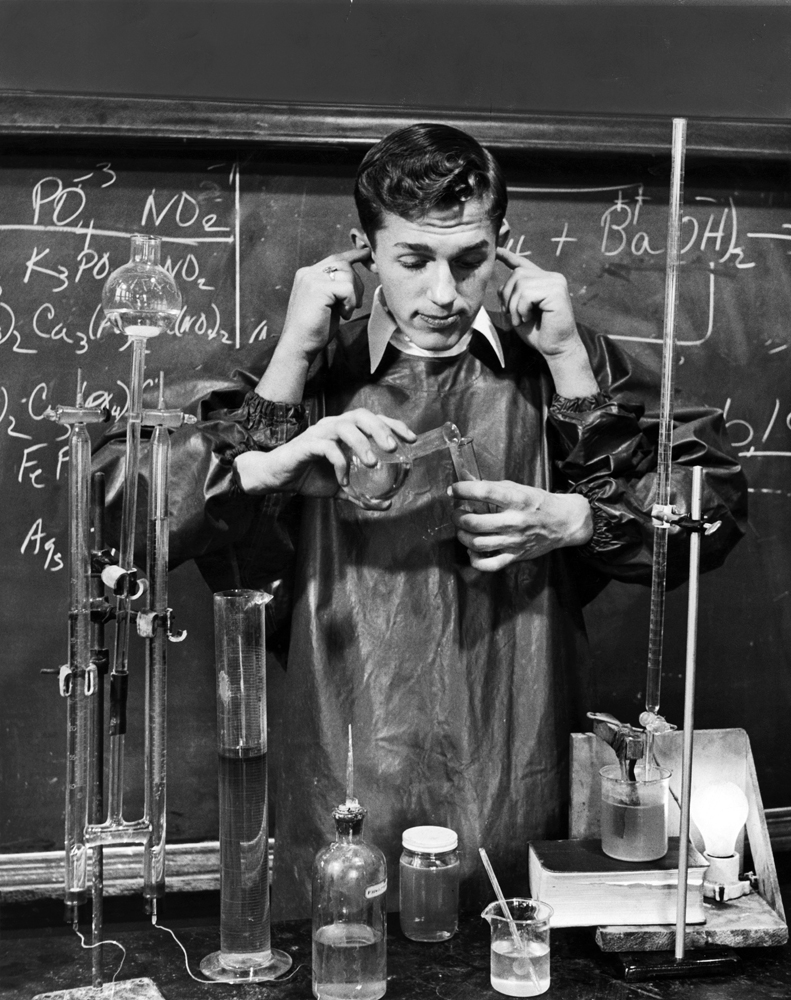

Happily, in recent research that I conducted, I found promising ways that middle school teachers are incorporating elements of play into their classrooms—with joyful results. In the classrooms I studied, sixth, seventh, and eighth graders developed governments for imaginary countries, researched and prepared “survival kits” for different climates, created board games to review social studies content they had learned, and “travelled to Afghanistan” in a game of physical geography on the playground. In each of these classroom exercises, students were allowed to make choices about what they wanted to learn, had opportunities to try on adult roles, were able to develop imaginative physical and mental creations, and importantly, enjoyed the process of learning.

Across the classrooms where teachers gave students these opportunities, the young adolescents I surveyed were happy and interested in their work. One said, “I have had one of the best school years because of this class.” Another seventh grader researched Ancient Egyptian mummification and showcased his learning in a creation he titled “Mummy monthly,” a clever magazine complete with cartoons and a reader quiz that asked, “Is your mommy a mummy?” His teacher explained to me, “this is a kid who we can hardly get to pick up a pencil.”

Similarly, in her study of high schools across the country, researcher Sarah Fine has shown the promise of what she terms “intellectual playfulness.” Amid the passive, rote, and dulling experiences that are all too common for adolescents, Fine found teachers like Ms. Hart, who gave students time to create “physics jamz,” songs they rewrote to review physics concepts and equations. Contrary to one high school administrator in Fine’s research who said, “You have to solve the problem of rigor before you can start to work on joy,” Ms. Hart’s physics jamz highlighted that students can find their work challenging and interesting, too.

Giving students occasions to learn through play not only fosters creative thinking, problem solving, independence, and perseverance, but also addresses teenagers’ developmental needs for greater independence and ownership in their learning, opportunities for physical activity and creative expression, and the ability to demonstrate competence. When classroom activities allow students to make choices relevant to their interests, direct their own learning, engage their imaginations, experiment with adult roles, and play physically, research shows that students become more motivated and interested, and they enjoy more positive school experiences.

To be sure, there are times to be serious in school. The complex study of genocide or racism in social studies classrooms, for example, warrant students’ thoughtful, ethical engagement, while crafting an evidence-based argument in support of a public policy calls upon another set of student skills and understandings. As with all good teaching, teachers must be deliberate about their aims. But, given that play allows for particular kinds of valuable learning and development, there should be room in school to cultivate all of these dimensions of adolescent potential.

Purposefully infusing play into middle and high school classrooms holds the potential for a more joyful, creative, and educative future for us all—a future in which kids have more interesting things to do in school than count down to summer break.

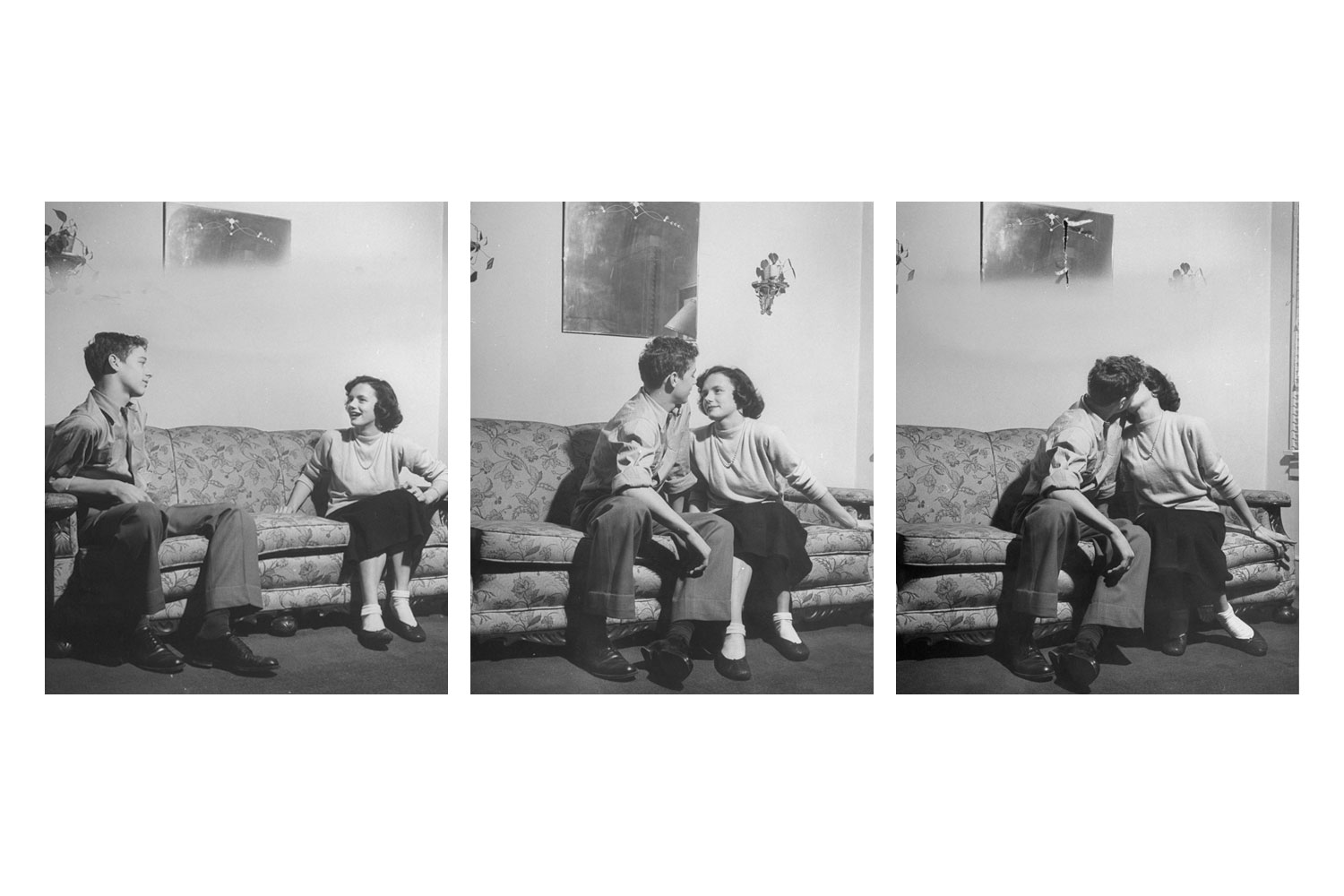

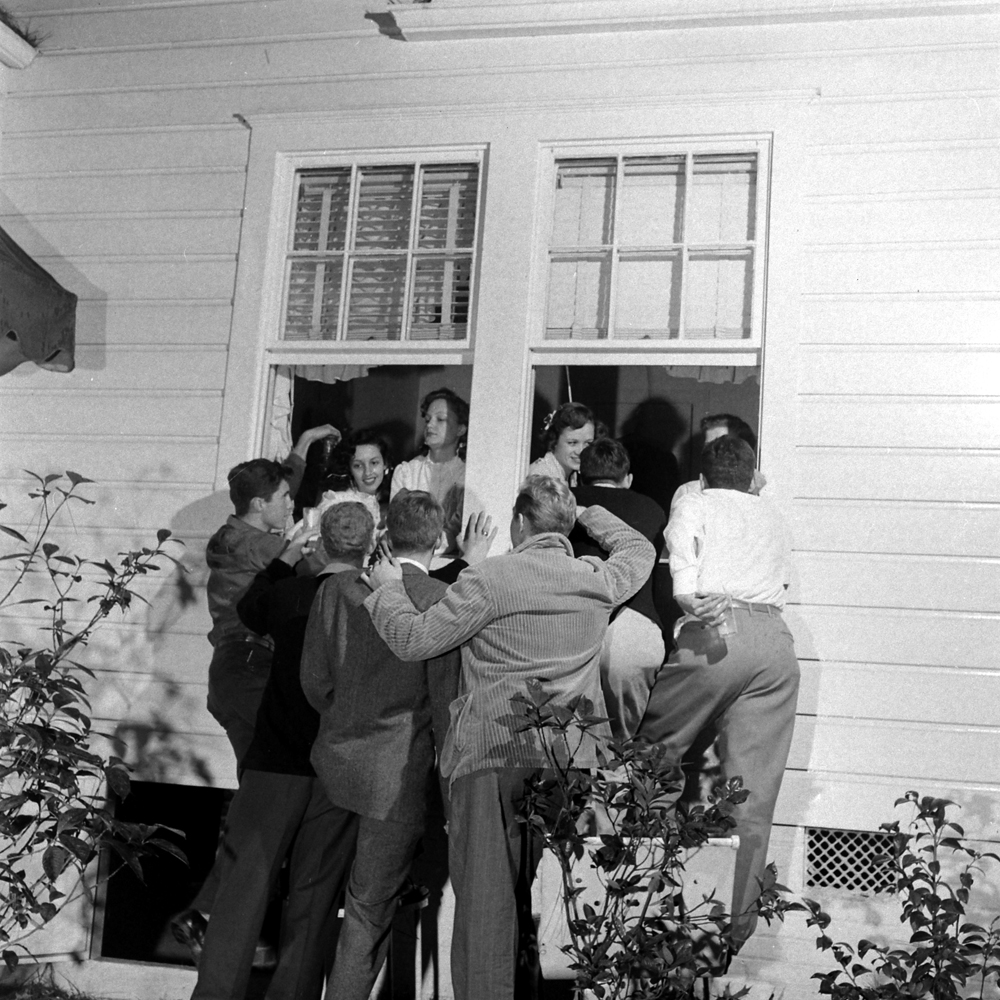

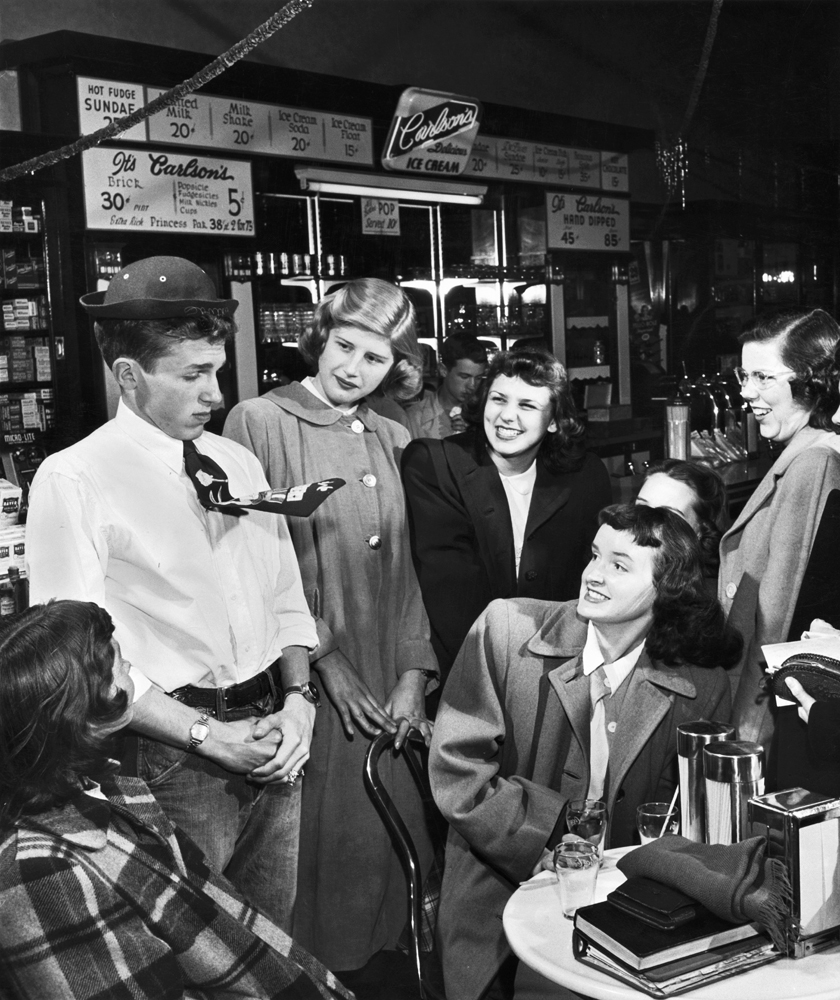

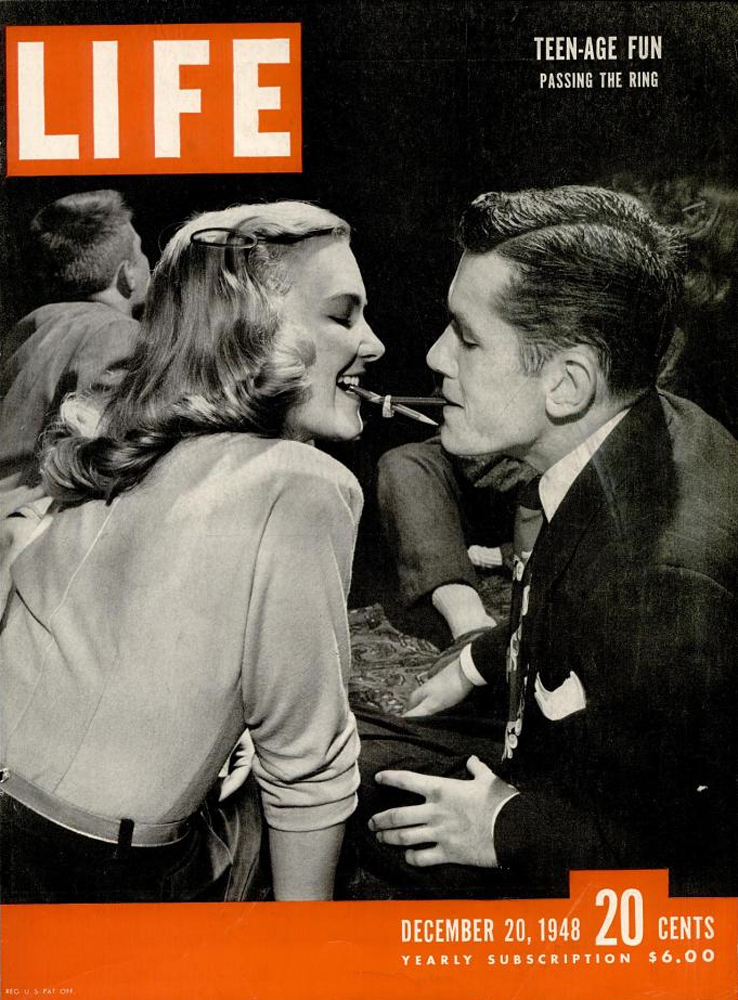

Teenage Fads From Around the U.S. in 1948

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com