Last summer, British photographer Guy Martin stumbled upon an unexpected gift shop in the suburbs of Istanbul, Turkey. It sold memorabilia associated with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. Martin speaks to TIME LightBox.

In Istanbul during the sweltering summer of 2014, I heard about a back street gift shop in the Istanbul district of Bagcilar.

In the Turkish city, gift shops are plentiful, offering a wide selection of plates, table coasters, badges, key rings and iPhone covers featuring the city’s Blue Mosque, Galatta tower, as well as photos of prime minister Tayip Erdogan and the young and iconic founder of modern Turkey, Ataturk.

I, however, was not on the hunt for the latest in Turkish gift shop trinkets. The gift shop that I wanted to find had a rather macabre, bizarre and terrifying premise: it sold memorabilia associated with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

The shape of Istanbul changes dramatically after you exit the city’s center with its towering mosques and century-old buildings. The hustle of the city gives way to grey, nondescript apartments, highways, overpasses and shopping malls.

Bagcilar looks like any of the city’s other outskirts with its kebab restaurants, mobile phone shops, and low-rise apartment blocks.

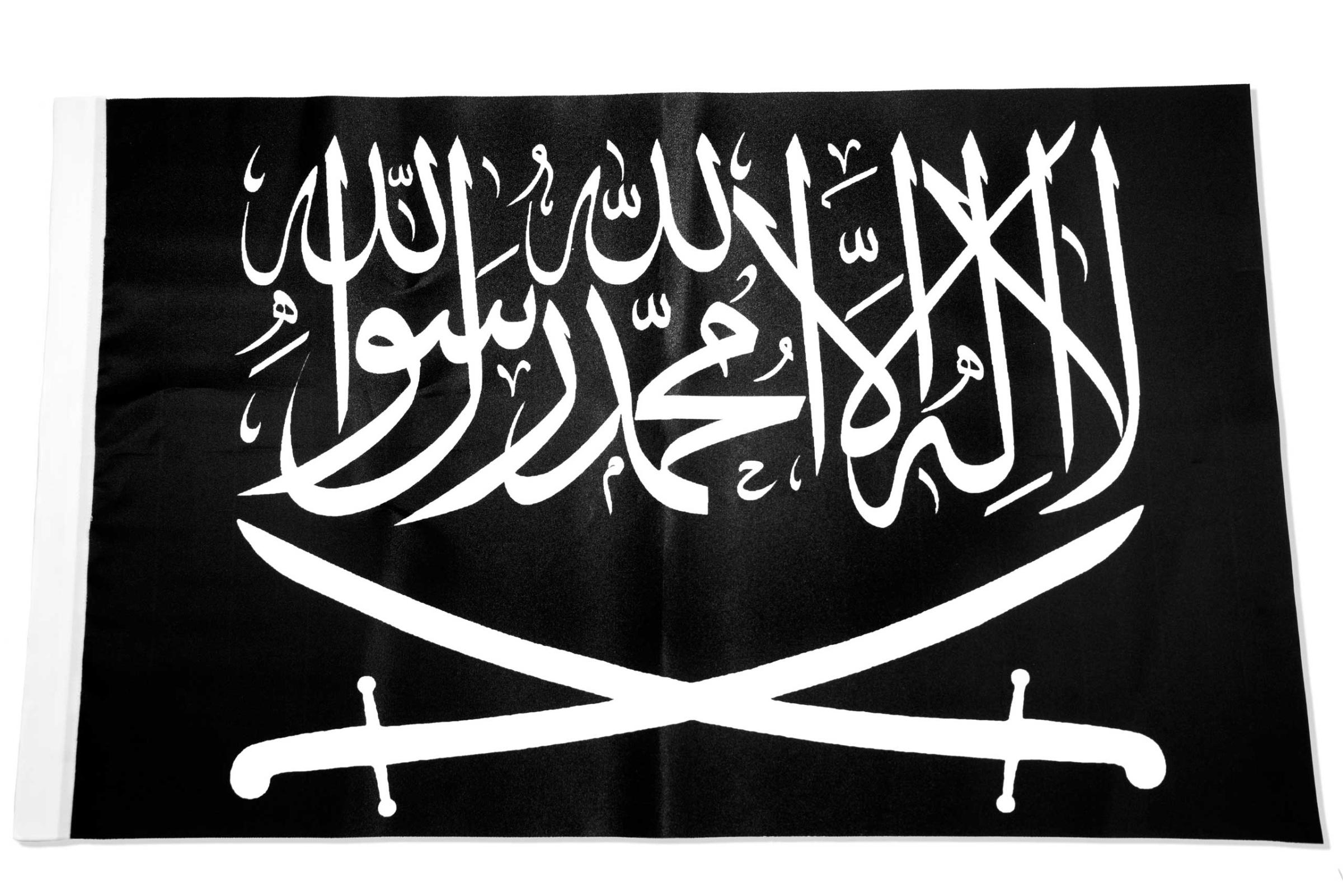

Walking to the end of a busy street, past a row of men’s clothing stores, which sold black skinny jeans, hoodies and knock off sneakers, and an upmarket Turkish restaurant serving fresh salads, mezze and barbecued meat dishes, I found it. The now infamous black flag, embellished with the seal of prophet Muhammad hung outside. In the shop windows: black t-shirts, key rings, cups and more flags.

My palms began to sweat as I approached the shop; images from gory and grainy YouTube videos fill my thoughts. But the shop was closed, and local residents didn’t seem to know who owned it.

I left that day, but for the next three weeks I returned to it again and again, hoping that it would be open. On my final visit, the shop was open. Sitting at the desk, were two women, their bare legs showing underneath a rolled up black Abaya, and their face veils thrown over their heads. They wore brand new, bright pink Nike trainers. They smoked and checked their Facebook accounts.

It took them a moment to realize they had a customer. When they saw me, they quickly covered their faces, stubbed out their cigarettes and walked towards me.

I was not allowed to photograph them or the inside of the shop, they said, but I could take pictures of various objects on a long white table.

I was aware of how rare an opportunity I had been afforded, but I also knew that I never wanted to return to this place again. It had been just a few days since James Foley’s brutal murder, and I could not help associating these items with the group’s vile acts.

Before we left, the two women denied any knowledge or association with terrorism, or that the products they were selling were funding terror groups.

I sat on these images for the rest of the year and with each week that passed, the brutality of ISIS’s acts just seemed to grow. I didn’t want to look them. I felt terrible for taking them. I felt, in some strange way, associated with these objects.

But as time passed and our understanding of ISIS grew, I needed to know more about those inanimate objects. What was striking about the objects I photographed was the variety of the symbols and iconography they featured. From the ‘Seal of the Prophet’ on a white flag – often used by Al Shabaab militants in Somalia and the Arabian Peninsula – to the green, white and red flags used by militant groups in the Caucasus. These logos and brands, as Arthur Beifuss and Francesco Trivini Bellini explain in Branding Terror – the Logotypes and Iconography of Insurgent Groups and Terrorist Organizations, are now an integral part of this global conflict. And, as I looked at the photographs I took that day, I was reminded not only of how global this conflict is but also what an integral role that marketing now plays to terrorist groups currently glamouring for attention in the “global war on terror”.

Guy Martin is a British photographer represented by Panos Pictures.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com