This week marks the 80th birthday of the Dionne Quintuplets — five identical sisters born prematurely in a small village in Ontario, Canada, in May 1934. The quintet were a money-making juggernaut in the 1930s and 1940s, put on display as public curiosities, while their private lives were marked by misery, betrayal and alleged abuse at the hands of those closest to them. The text below is an edited version of an article that Dennis Gaffney wrote on the quintuplets for WGBH’s Antiques Roadshow site.

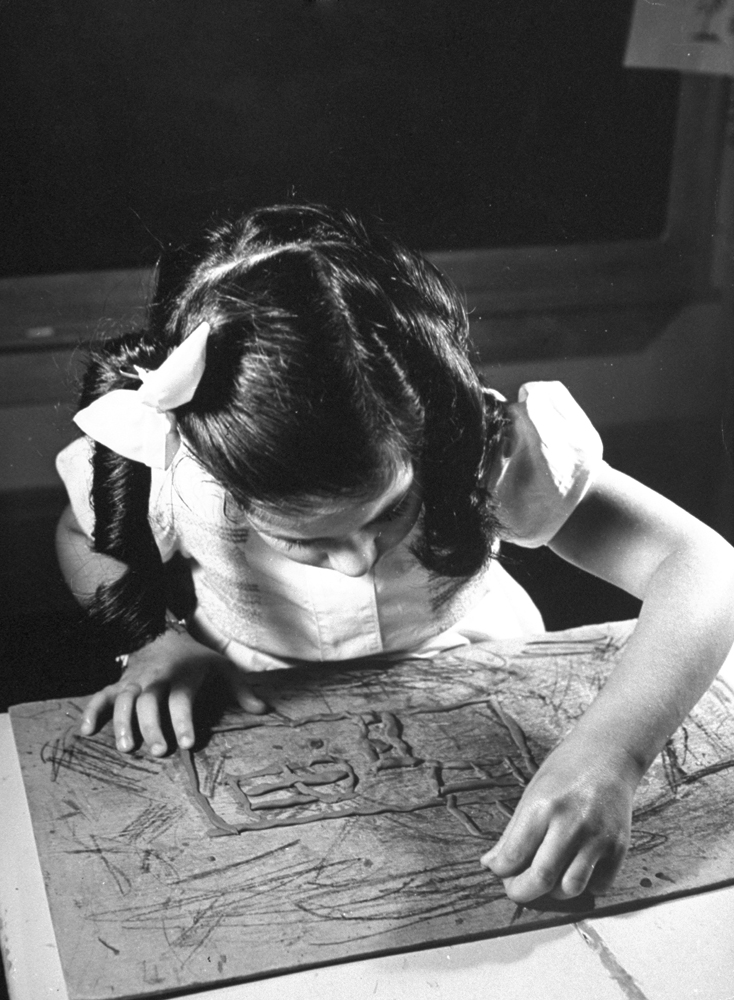

It’s worth noting, meanwhile, that while LIFE magazine — in its own way, and like so many other publications — contributed to the exploitation of the “Quins,” the magazine did have the sense to sound some prescient warnings about the nature of the quintuplets’ unusual and intensely proscribed upbringing. “Their formal schooling,” LIFE wrote in its Sept. 2, 1940, issue, “will never constitute a real education until the children can be exposed to the rough and tumble of life with less-supervised contemporaries. They have . . . developed no social immunities to the unprotected existence that they will someday have to face.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________

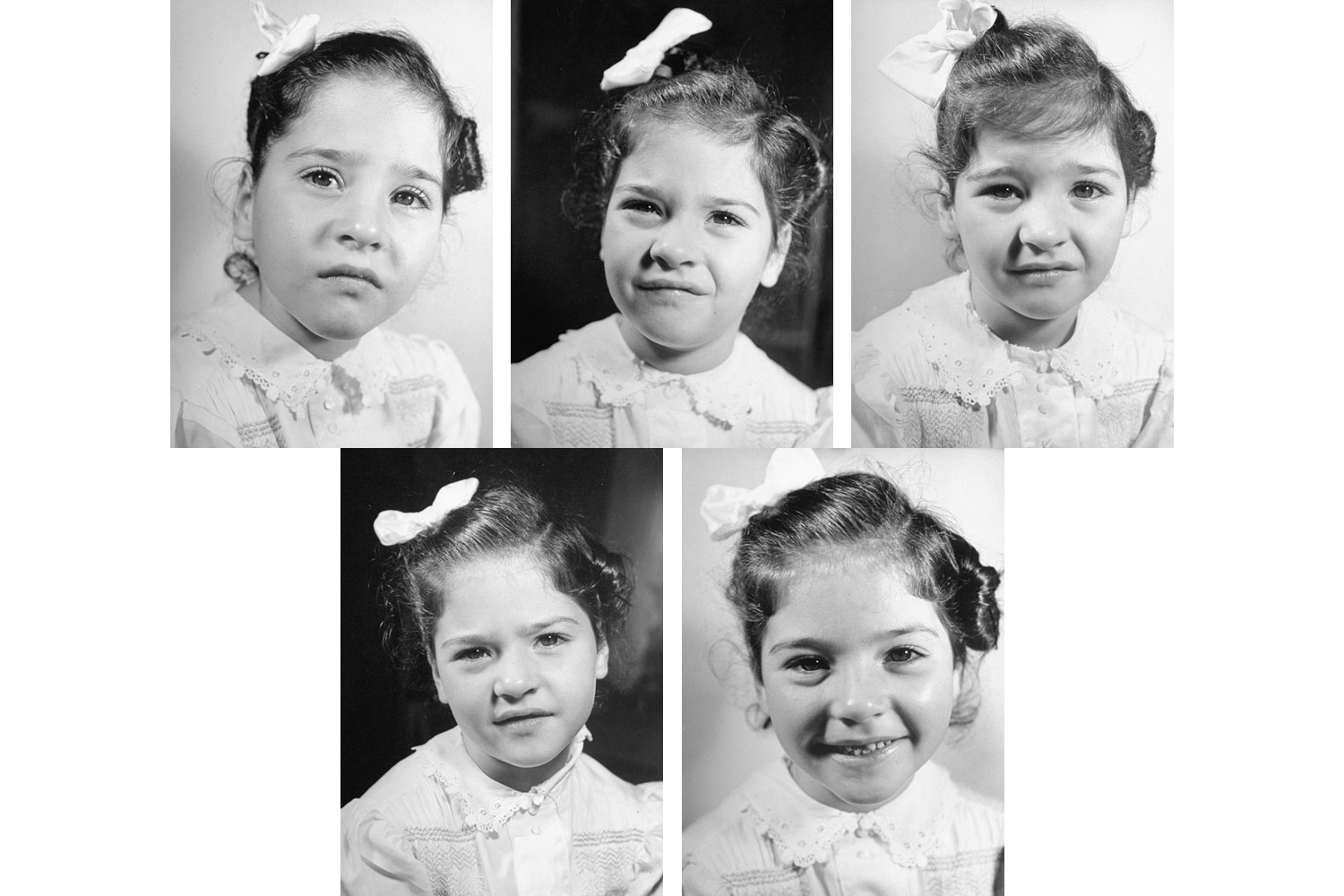

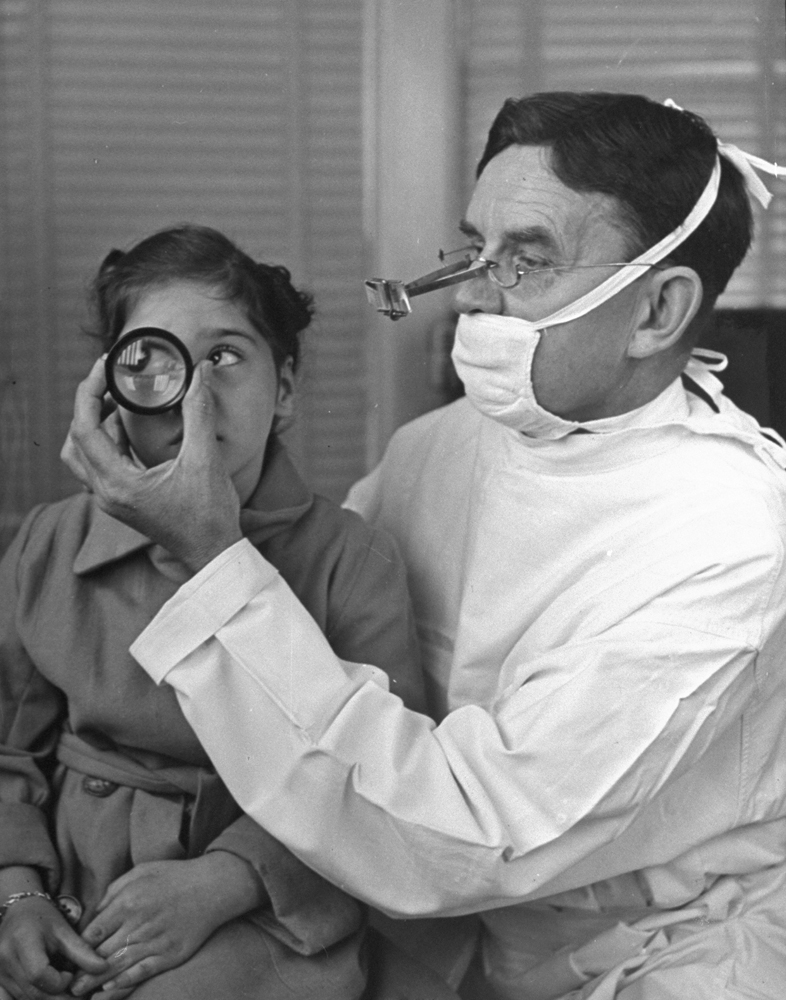

On May 28, 1934, on a farm in the village of Corbeil, Ontario, near the Quebec border, a French-Canadian mother, Elzire Dionne, gave birth to five identical girls — Annette, Emilie, Yvonne, Cecile, and Marie. Born at least two months prematurely, each baby was small enough to be held in one hand; together they weighed only 14 pounds. Few expected they would survive . . . . But they did, and became the first quintuplets known to have survived infancy.

Soon the world was referring to the Dionne quintuplets as “miracle babies,” and they became a worldwide symbol of fortitude and joy during the Great Depression.

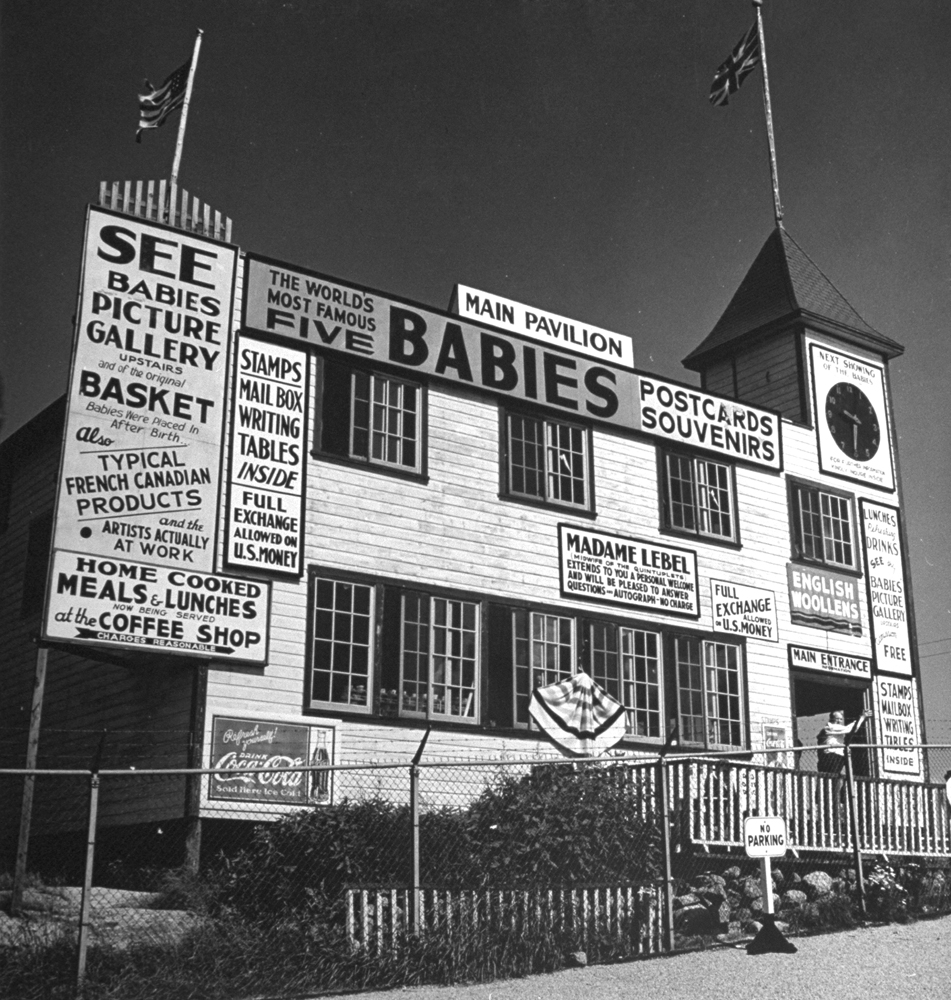

The girls themselves became a tourist attraction. By 1937, about 3,000 visitors were passing daily through the “Quintland” hospital compound where the sisters were being cared for. . . . Hollywood exploited their fame, and four movies were made about them in the 1930s — all with happy endings.

But the real lives of the Dionne quintuplets were largely unhappy. On May 27, 1935, the provincial government of Ontario had taken the five sisters away from their parents, after their father, Oliva, signed a contract with promoters to exhibit the girls at the World’s Fair in Chicago. Although Oliva cancelled the contract a day after he signed it, the authorities stepped in anyway to protect the babies, they said, from germs, potential kidnappers, and exploitation.

Yet it was in the custody of the state that the girls became Canada’s largest tourist attraction. During the girls’ infancy, nurses would take them to a nursery balcony and show them one at a time to a crowd below, their names written on a card. In the media, the girls’ upbringing was characterized as privileged, with round-the-clock nursing and a swimming pool and playground all their own. But in reality their playground was surrounded with glass that allowed visitors to view them three times a day.

In their 1963 autobiography, We Were Five, they wrote of being isolated from others during their upbringing, only permitted to leave the compound a few times. “We dwelt at the center of a circus,” they wrote. “A carnival set in the middle of nowhere.” According to some estimates, Quintland brought in as much as $500 million to the Ontario province in less than a decade.

“Money was the monster,” they said in We Were Five, “So many around us were unable to resist the temptation.” Although their parents lived across the street from Quintland, the couple felt unwelcome there, and became infrequent visitors. “We didn’t know each other,” Cecile recalled.

At age 9, the Dionne couple won the girls back after a bitter custody battle, yet the girls’ new home was “the saddest home we ever knew,” they later wrote. They didn’t perceive their parents as saviors from Quintland; they came to see their mother as unloving and their father as controlling, even tyrannical.

At age 18, the Dionne sisters left home, breaking off nearly all contact with their family. Emilie became a nun and died of a seizure in 1954. Three married and had children, but divorced. Marie died of a blood clot in 1970. In the mid-1990s, the three remaining sisters — Annette, Cecile, and Yvonne — wrote in their book The Dionne Quintuplets: Family Secrets that their father had abused when he took them alone in the car.

Despite the enormous revenue generated by the quintuplets as a public curiosity, by 1941, when the girls were 7, only $1 million had been put in their trust fund; when they turned 21 and became eligible to receive the funds, only $800,000 remained. Their sheltered life did not prepare them for the real world, and when they were on their own Cecile said the girls had difficulty distinguishing a nickel from a quarter.

What funds they were provided eventually disappeared, and when Annette, Cecile and Yvonne reached their sixties, they lived together outside Montreal on a combined income of $746 a month. In 1998, they asked the Canadian government to compensate them for the trust fund money that had been lost or taken. The government’s first reply included an offer of $2,000 a month, but after a public outcry, a $4 million settlement was reached.

Yvonne died in 2001, leaving Cecile and Annette as the two surviving sisters.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Dennis Gaffney is a writer based in Albany, New York, who has written for the New York Times, Reader’s Digest, Mother Jones and other publications, as well as for online outlets like the companion sites for PBS’s Antiques Roadshow and American Experience.

The text above is published here courtesy of Dennis Gaffney and WGBH/Antiques Roadshow.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com