The marches that took place in Selma 50 years ago this month never would have happened without Martin Luther King, John Lewis, Hosea Williams and the cadre of civil rights leaders who organized the charge. They might not have happened if not for the tragic death of Jimmie Lee Jackson, and they certainly couldn’t have made the splash they did without the thousands of people who showed up to put feet to the pavement and march—some at the cost of bodily harm, and two at the cost of their lives.

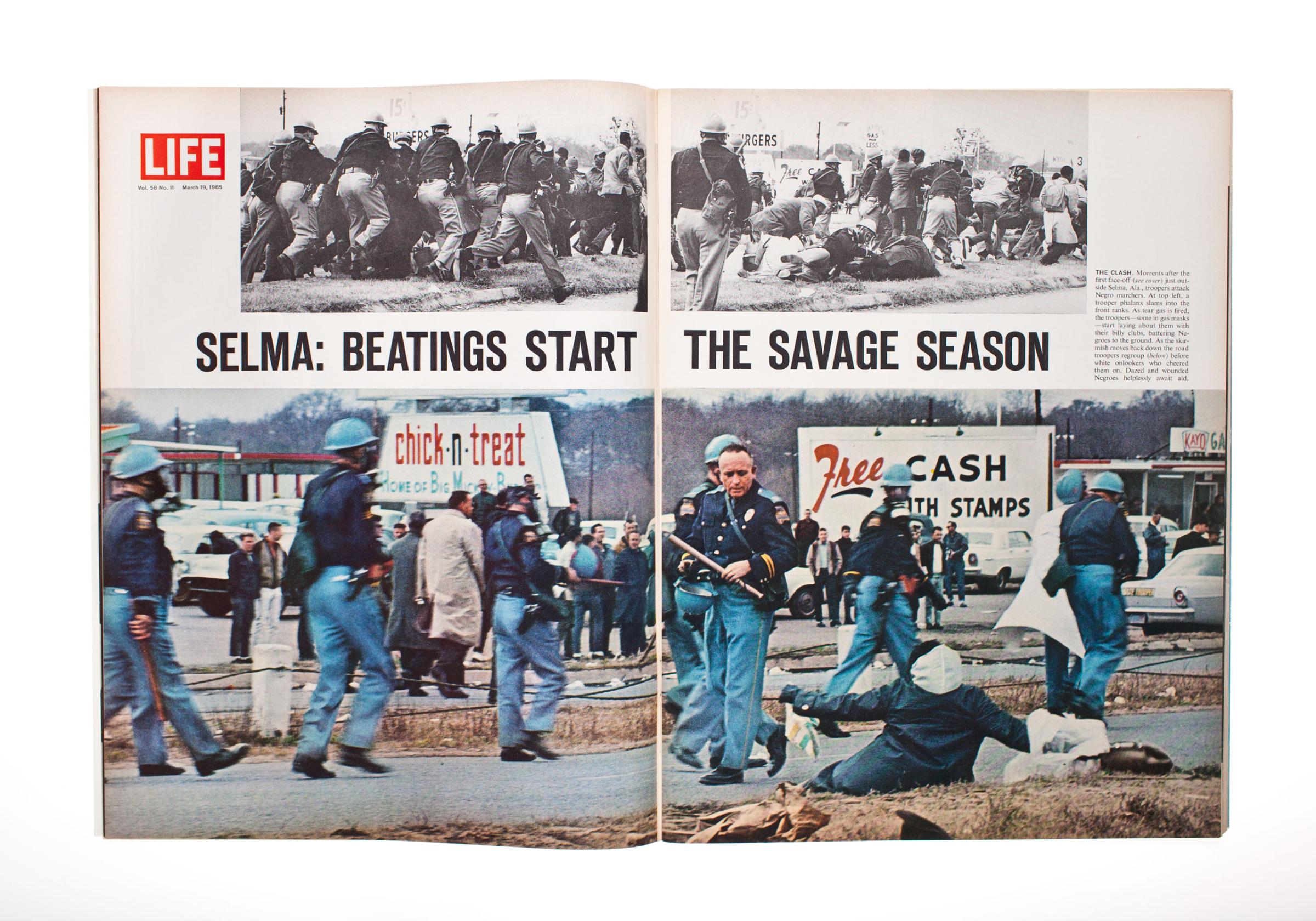

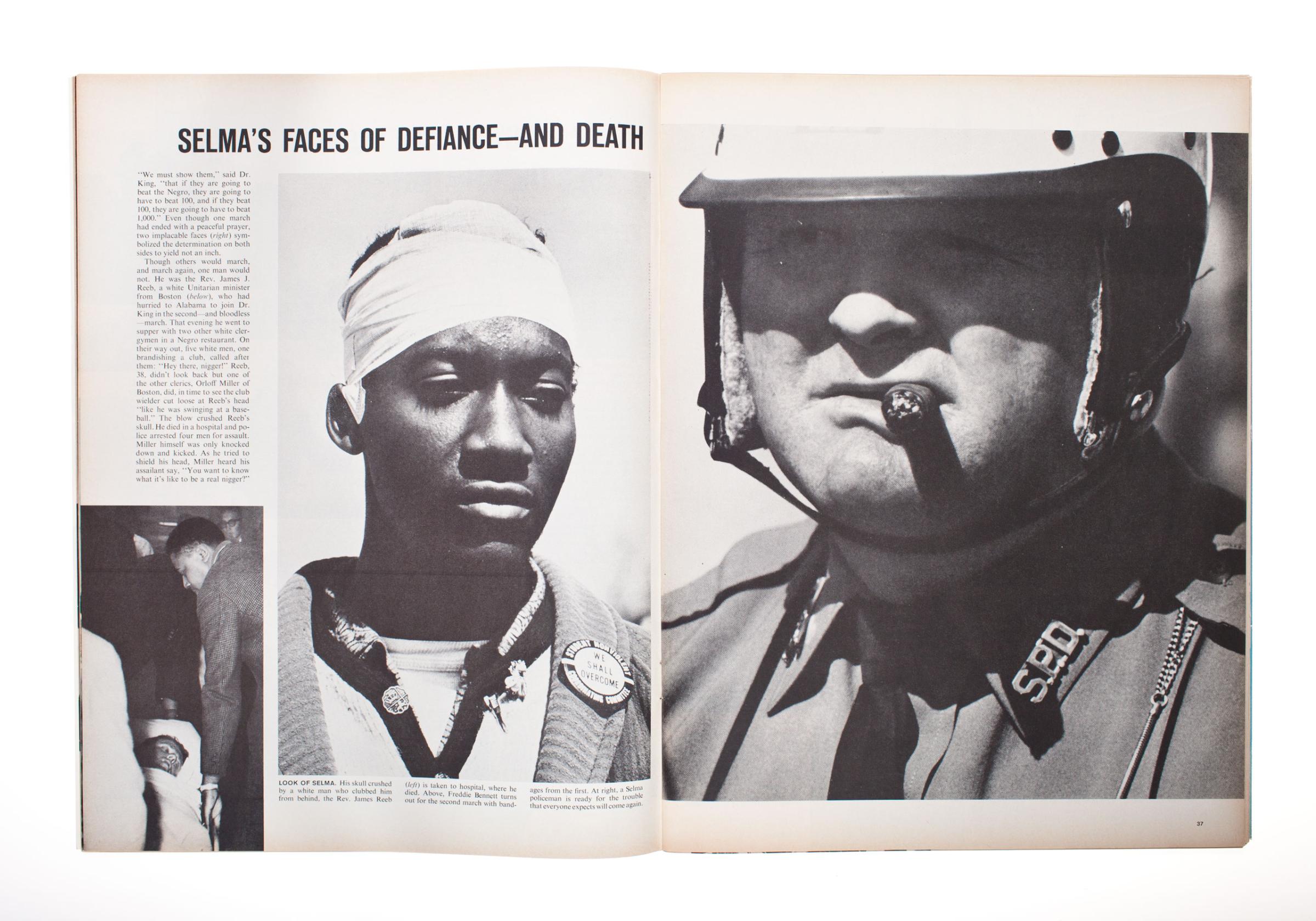

And their courageous actions would have gone unseen if not for the photojournalists on the ground to document the brutality they faced for the world to see. The images they created—of Alabama state troopers rushing peaceful protestors like a monolithic mob, wielding weapons and riot gear that conjure war photography—helped fuel the public outrage to which the Johnson administration had no choice but to respond.

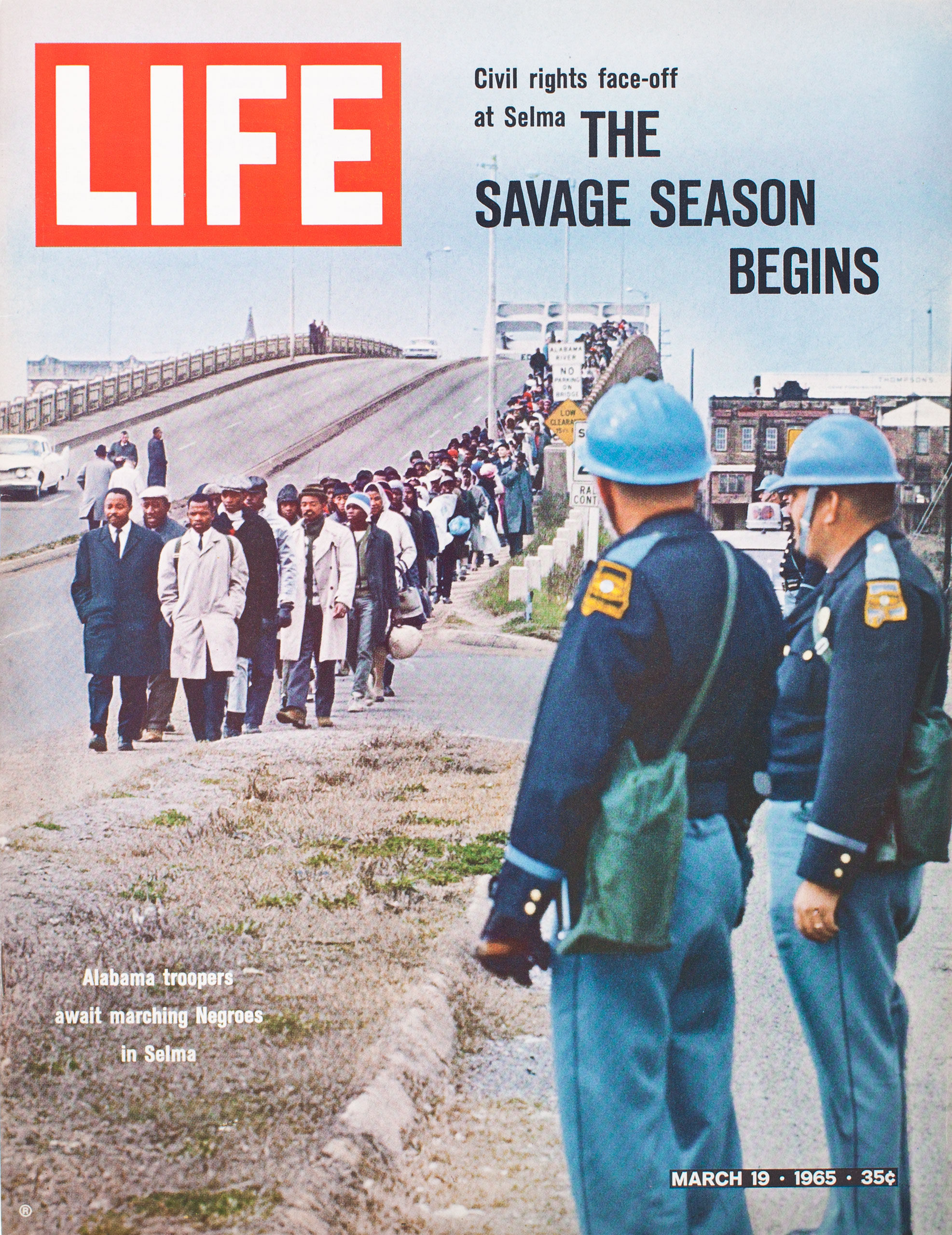

LIFE’s coverage of the marches began in its March 19, 1965 issue, the cover of which shows a line of solemn marchers, two by two, disappearing over the horizon as helmeted troopers look on. By the time the issue was published, the protesters had made two attempts to march.

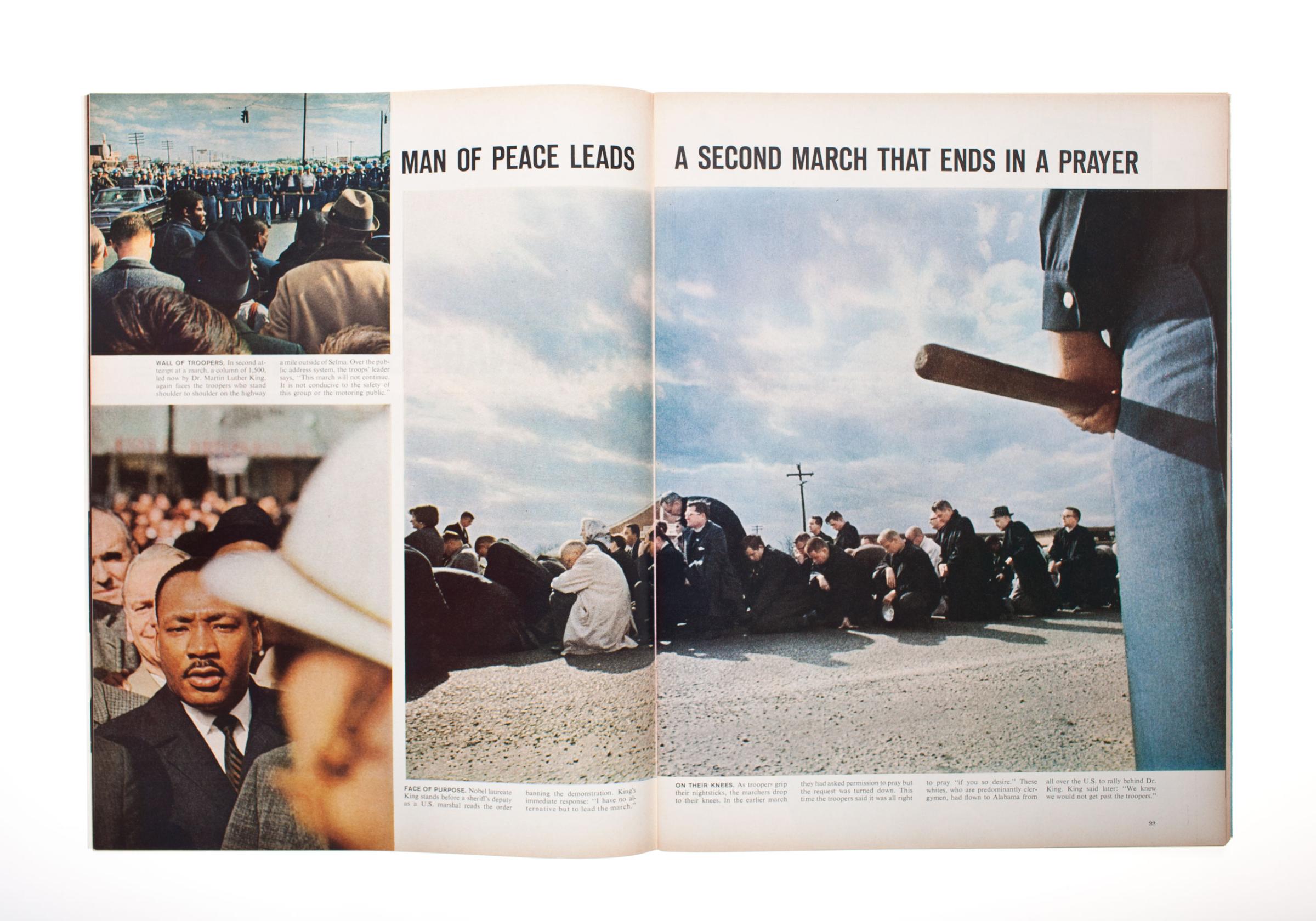

The first, on March 7, later referred to as “Bloody Sunday,” ended with troopers attacking the marchers in a scene that was nothing if not savage, sending 17 to the hospital with injuries. The second, two days later, ended in peaceful prayer, with King ordering the marchers to halt so as not to defy a pending restraining order. This day would come to be known as “Turnaround Tuesday.”

The March to Montgomery began on March 21, two days after the issue was published, and ended on March 25 at the Alabama State Capitol Building. As LIFE described the convergence of nuns, students and Americans of all races the following week in Selma, “In all the turbulent history of civil rights, never had there been such a widespread reaction to the doctrine of white supremacy.”

The photographs, by Charles Moore, Flip Schulke and Frank Dandridge, offered the magazine’s 7 million readers no equivocation as to what it meant to be black in America in 1965. And the images of violence, solidarity, prayer and resilience achieved the greatest results a photograph can hope to achieve: empathy, understanding and above all, social change.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com