This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

It has become a commonplace to compare today’s economic and political news with interwar Europe. The Great Recession is measured against the Great Depression and Paul Krugman has recently suggested that demands being made on Greece are like those the Treaty of Versailles imposed on Germany. In his new Hall of Mirrors, however, economist Barry Eichengreen argues that repeated comparison of our current moment with the 1930s has resulted in poor policy decisions. Policymakers managed to avert another depression but, once they did so, their mission seemed complete and their hands were tied. Radical reforms—of the type necessary to prevent another recession—proved politically impossible.

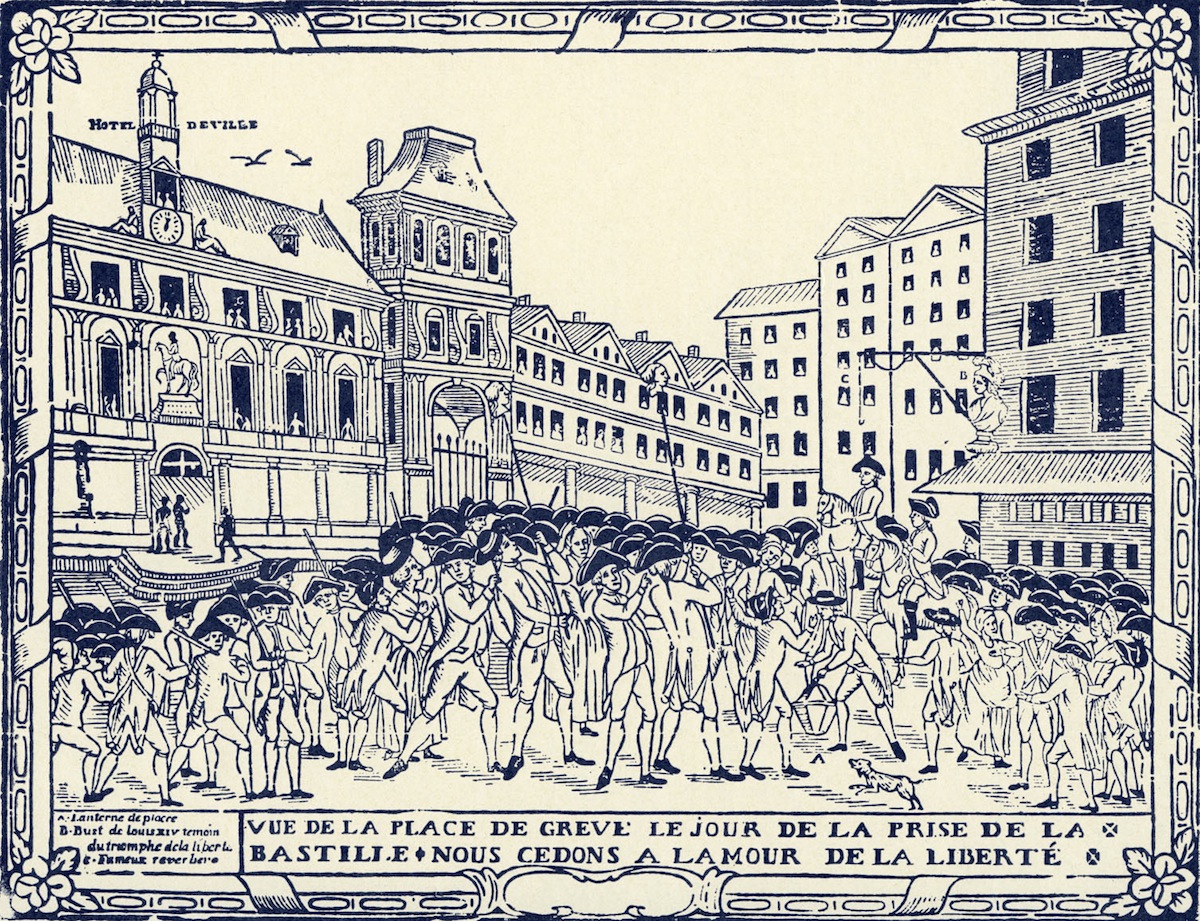

The moment has come to diversify our analogy portfolio. What happens, for instance, if we think about the Eurozone crisis in terms provided by the history of the French Revolution? The comparison may initially seem contrived, but it offers significant lessons nonetheless.

Consider: debt dominated public debate in 1780s France as it does in Eurozone negotiations today. For decades, the monarchy had struggled to effectively tax the Catholic Church and the nobility. For decades, as Michael Kwass has conclusively shown, the wealthy and super wealthy branded such efforts despotic; they used the resulting power struggles to their own, political ends. Appealing repeatedly to notions of the public good—new taxes would mean “the loss of our liberty, the destruction of our laws, the ruin of our commerce, and the desperate misery of the people”—they blocked all attempts to spread taxation more fairly. Social elites thereby successfully defended their own riches, made themselves popular spokesmen for the common good, and pushed France further into borrowing (since it could not tax). Norman noblemen and Paris magistrates were the Koch Brothers of their day: bent on conserving their own privileges by fueling grass-roots populism. Their effective depiction of the monarchy’s fiscal crisis as a result of its own opulence—even now, don’t we imagine the money was spent on Marie Antoinette’s dresses and the King’s hunting dogs?—made state finances look like moral, rather than political, issues. (For in-depth discussion of this point, see Clare Haru Crowston’s Credit, Fashion, Sex and John Shovlin’s Political Economy of Virtue).

Like many in the United States and Europe today, these critics of the centralizing monarchy played politics with money. None of these men—all members of the privileged elite—intended to start a revolution. But by blocking needed tax reform, they provoked a political showdown that eventually turned summer 1789 into a social, cultural, and economic crisis of unparalleled proportions.

Lesson One Revolutions are their most revolutionary when no one sees them coming.

Money and debt played a crucial role in further revolutionizing France. In one of the first acts of the Revolution (prior even to the storming of the Bastille), the National Assembly declared France’s existing debt “sacred.” Unlike the later Bolsheviks (who in 1918 defaulted on everything the Russian Empire had borrowed, thereby giving rise to the doctrine of Odious Debt), the French revolutionaries accepted an inherited burden. The formerly royal debt became the national debt, and the new political body faced the same fiscal problems as had the old. At the same time, however, the National Assembly also challenged all existing taxes because they had been imposed by the monarch alone (the French version of “no taxation without representation”). Monetary-fiscal policy at this point was not intentionally revolutionary. The National Assembly was in many ways conservative. Like Angela Merkel’s Germany and other core economies today, it insisted that debts had to be honored and bills had to be paid. Like critics of quantitative easing, its members recoiled from the thought of merely printing money. They demanded that France put “solid assets” behind its promises to creditors.

With debt on the books and taxes delegitimized, a small majority within the National Assembly moved to nationalize and then monetize lands held by the Catholic Church. Here any parallel between the current moment and the 1790s appears to break down. Today, austerity means shrinking the public sector, whereas balancing the budget in 1789 involved expanding it (since the state took over the Church’s traditional welfare-providing role as well as its property). The social effects of the measures, however, were strikingly similar: widespread resistance, popular unrest, and growing political polarization. And, as today, uncertainty and confused expectations led investors to flee risk and seek safe places to put their money. Commercial credit, the backbone of eighteenth-century economic growth, dried up overnight. Lack of confidence in the new regime quickly metastasized into a generalized collapse in trust. All debts came due at once.

Lesson Two Insisting on balanced books and sound money may be conservative rhetoric but it often has radical effects.

Since Maastricht, the EU has tried to use currency to create a stronger sense of European identity. So too did policymakers in 1790s France, who believed widespread use of a new currency (paper notes backed by the value of the nationalized properties) would force people to “buy into” the Revolution whether they supported its politics or not.

Like many Europeans and Americans today, most revolutionaries in the 1790s understood “liberty” as entailing both political freedom and market non-regulation. The majority within the National Assembly therefore embraced free trade in money as they had in grain. Radical monetary liberty—such that any merchant was free to accept the nationally issued paper for less than its face value—pushed both freedom and money to their breaking point.

As does the European Union, the French Revolution emphasized equality, rights, and citizenship. In both contexts, this political rhetoric collides with the social reality of growing inequality to create a feedback loop. A political choice (be it free trade in money or European monetary union) disrupts social-economic life; that disruption makes political ideals (such as liberty) seem all the more desirable and elusive; upholding those ideals causes further economic dislocation and social uncertainty.

Lesson Three Playing politics with money is a sure way to make policy decisions matter to ordinary people. The results are often explosive.

Rebecca L. Spang is the author of “Stuff and Money in the Time of the French Revolution” (Harvard University Press, 2015) and a faculty member at Indiana University, where she directs the Center for Eighteenth-Century Studies and is the Acting Director of the Institute for European Studies. Her first book, “The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture” was also published by Harvard.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com