From the day of its world premiere 50 years ago, on Mar. 2, 1965, just about everyone knew that The Sound of Music was a great movie. Audiences flocked to it like the ecstatic faithful at a Sunday service that rewarded their devotion with its high purpose, beautiful hymns and an angelic choir. They quickly made it the most popular attraction in the first half-century of the Hollywood feature film, not eclipsed until Star Wars a dozen years later. Indeed, in terms of tickets sold in its initial theatrical run, The Sound of Music trails only Gone With the Wind (another movie about a strong woman in a prewar crisis) as the biggest hit of all time.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences loved the movie big time, festooning it with 10 nominations and five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director, at the 1966 ceremony. The startling highlight of last week’s Oscar show was Lady Gaga singing four of Richard Rodgers’ and Oscar Hammerstein II’s hits from the movie. The pitch-perfect medley won Gaga a dewy hug from Julie Andrews, the film’s indelible Maria von Trapp, and a commendation from von Trapp’s 60-year-old granddaughter Elizabeth, who wrote, “Lady Gaga’s celebration at the Oscars was exquisite — her voice being perfect for the medley — and beautifully choreographed.”

The soundtrack album, with its bounty of semi-operatic ballads, spent its first four years on Billboard’s Top Album charts in the U.S. — this in the full flush of Beatlemania — and was No. 1 for 70 weeks in the U.K.

All in all, the film won near-universal acclaim from viewers, listeners and the industry.

From everyone but the movie critics, that is. Many of these sour skeptics TP’d the Rodgers-and-Hammerstein cathedral with reviews that ranged from mixed to malevolent. The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther, dean of mainstream reviewers, excoriated the movie as “cosy-cum-corny,” its adult characters as “fairly horrendous” and Andrews’ Maria as “always in peril of collapsing under [the movie’s] weight of romantic nonsense and sentiment.” In a more measured tone, the anonymous critic for TIME magazine wrote that the movie “contains too much sugar, too little spice,” adding:

Viewers who want a movie to swell around them in big warm blobs will find Sound of Music easy to take. Sterner types may resist at the outset, but are apt to loosen up after a buoyant, heels-in-the-air song or two by Julie Andrews.

(Read TIME’s full review of The Sound of Music here in the TIME archives: R-H Positive)

The definitive denunciation came from Pauline Kael, soon to be the country’s most influential film critic. In a review so venomous it reportedly got her fired from her post at McCall’s, Kael called The Sound of Music “the sugarcoated lie that people seem to want to eat” and “the single most repressive influence on artistic freedom in movies.”

That prediction turned out to be faulty, since within a few years movies had found their “artistic freedom,” awash in crimson violence (The Wild Bunch), explicit sexuality (I Am Curious) and the full four-letter lexicon (Medium Cool). The Sound of Music was not the ill wind that Kael detected but the last gasp of the studio system’s belief in G-rated operettas of inspirational uplift.

As a 1959 Broadway show, it was already an anachronism, surrounded by the brassier, more urgent West Side Story, Gypsy and Fiorello! By 1965, in the wake of the British Invasion, the Beach Boys, the Motown Sound and, the summer before, The Beatles’ hit movie A Hard Day’s Night, the project should have been a musty musical antique, like grandma’s Caruso 78s, long ago consigned to the attic.

Yet what seemed untimely turned out to be timeless. Unlike A Hard Day’s Night and the decade’s other zeitgeist movies, The Sound of Music seems hatched not from the go-go ’60s but from some primordial dream of sanctified surrogate motherhood. In its tale of a governess who is both liberal and liberating to her charges and their gruff father, it touched the hearts of those with happy family memories and of everyone else who didn’t have them but wished they did.

In Andrews, fresh from her Oscar-winning turn as a sterner nanny in Mary Poppins, the movie found the ideal vessel for Maria’s stubborn sunniness, and for her missionary zeal to save naval Captain Georg von Trapp (Christopher Plummer), the starchy Austrian widower who needs a nun-on-loan to restore his humanity.

Directed by Robert Wise and scripted by Ernest Lehman—who had previously collaborated on the movie version of West Side Story—The Sound of Music wove its songs into political melodrama, an escapist tale about escaping the Nazis. In doing so, it joined 70 years of World War II films, from Mrs. Miniver and Casablanca to Schindler’s List and The King’s Speech, in the roll call of Best Picture Oscar winners whose (unseen) villain was Hitler.

Over the decades, through sing-along editions in theaters and a top-rated live TV production in 2013, the property has never relinquished its magic for audiences. Fifty years after its release, even a cranky-guy critic would have to give this candied confection its due: the darn thing works.

TURNING A TRUE STORY INTO A MUSICAL

In their plush melodies and plummy platitudes, many Rodgers-and-Hammerstein songs were secular hymns, which so insinuated themselves into the ear of the Eisenhower-era listener that they became the liturgical music for the American mid-century. “You’ll Never Walk Alone” from Carousel was our true national anthem, with The Sound of Music’s “Climb Ev’ry Mountain” — “Follow every rainbow / ’Til you find your dream” — a close second.

Though an R&H musical might address such dark issues as marital abuse (Carousel) and racial prejudice (South Pacific), the prevailing mood was unabashedly upbeat: whistling a happy tune, raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens. The melodies were so diligently soaring and the lyrics so wholesome — “a cliché coming true” — that, while you listened to them, they practically brushed your teeth and did your homework for you.

With his previous writing partner, Lorenz Hart, Rodgers had virtually established 20th-century Broadway sophistication in songs like “Manhattan,” “My Funny Valentine” and “The Lady Is a Tramp.” But whereas Hart’s lyrics, set to the modern 4/4 beat, were urban, up-to-date and skeptical, Hammerstein’s, often in waltz time, were rural, folksy and heartfelt; he was the perpetual cockeyed optimist.

“The most important ingredient of a good song is sincerity,” he wrote in a 1949 collection of his lyrics. “Mean it from the bottom of your heart, and say what is on your mind as carefully, as clearly, as beautifully as you can.” Introducing the book, Rodgers rightly said of his partner’s lyrics “that they are wonderful words, that they sing well of this country, and that they form a long and lasting part of our song heritage.” Though Hammerstein died at 65 in 1960, nine months into The Sound of Music’s Broadway run, the movie has proved how lasting that heritage would be.

He and Rodgers first teamed up when Hart sensibly decided that the farmers-vs.-cowboys Western story that would become Oklahoma! was not quite in his wheelhouse. (Hart died at 48 in 1943, the same year Oklahoma! opened.) The show was a history-making smash, with a then-record Broadway run of five years and 2,212 performances. Following up with Carousel (1945, 2 years), South Pacific (1949, four years and nine months) and The King and I (1951, three years), Rodgers and Hammerstein basically created the blockbuster musical.

Their sonorous shows lured tourists to Broadway and brought Broadway to America; the Oklahoma! road company kept going for an amazing 10½ years, until 1954, when the movie version was already in production to extend the franchise into a new medium that preserved it for generations of filmgoers and home viewers. Within a decade of Oklahoma!’s release, all six of R&H’s hit Broadway musicals (they had three flops: Allegro, Me and Juliet and Pipe Dream) were made into movies.

In 1958, Dick and Oscar were honing Flower Drum Song (which would run one year and seven months) when they were approached to write the songs for the story of the Trapp Family Singers to a book by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse. Starring Mary Martin, their Nellie Forbush from South Pacific, this would be the songwriters’ final collaboration and, with a three-year seven-month stint on Broadway, one of their most popular.

The only R&H show for which Hammerstein did not write the book, The Sound of Music is nonetheless suffused with the songwriters’ ethic. If not their best work (we’d choose Carousel or The King and I), it’s certainly the most Rodgers-and-Hammerstein musical — a summation of their love for plucky heroines in the wide-open spaces.

Before Oklahoma!, the Broadway musical had been an indoor sport. Hammerstein yanked it into the wide world outside. Staring out the window of his Doylestown, Pa., farmhouse, he wrote the first words of the first song in his first show with Rodgers: “There’s a bright golden haze on the meadow.” Nature ran rampant through his lyrics, from Oklahoma! to The Sound of Music, with its title tune set in the Austrian Alps: “My heart wants to sigh like a chime that flies / From the lake to the trees.”

On the stage during that song, Maria was backed by a canvas drop that could only hint at the grandeur infusing her. The first reason to make the show into a movie was that the helicoptering camera could bring the hills alive (with you-know-what). Aided by Boris Leven’s superb production design, the audience could see, not just imagine, the vistas that made Maria’s heart sing.

If Maria Rainer von Trapp had not existed, R&H might have invented her, so snugly did she fit their mold of the resilient innocent in a foreign land (South Pacific) with a brood of children to teach (The King and I). Born in 1905 and soon orphaned, the real Maria entered a convent as a postulant and was assigned to tutor the family of Captain von Trapp, a widower more than twice her age. (A naïf who was barely older than the eldest of her charges — she was 21 going on 17 — Maria must have grown up fast: a year later, she married the 47-year-old Captain.)

Shifting the chronology to 1938, when Germany annexed Austria, the show’s and the movie’s creators found in Maria a true musical heroine: music defined her soul. Its therapeutic power gives her joy and meaning; it also gives life, almost literally, to the family she joins and mends.

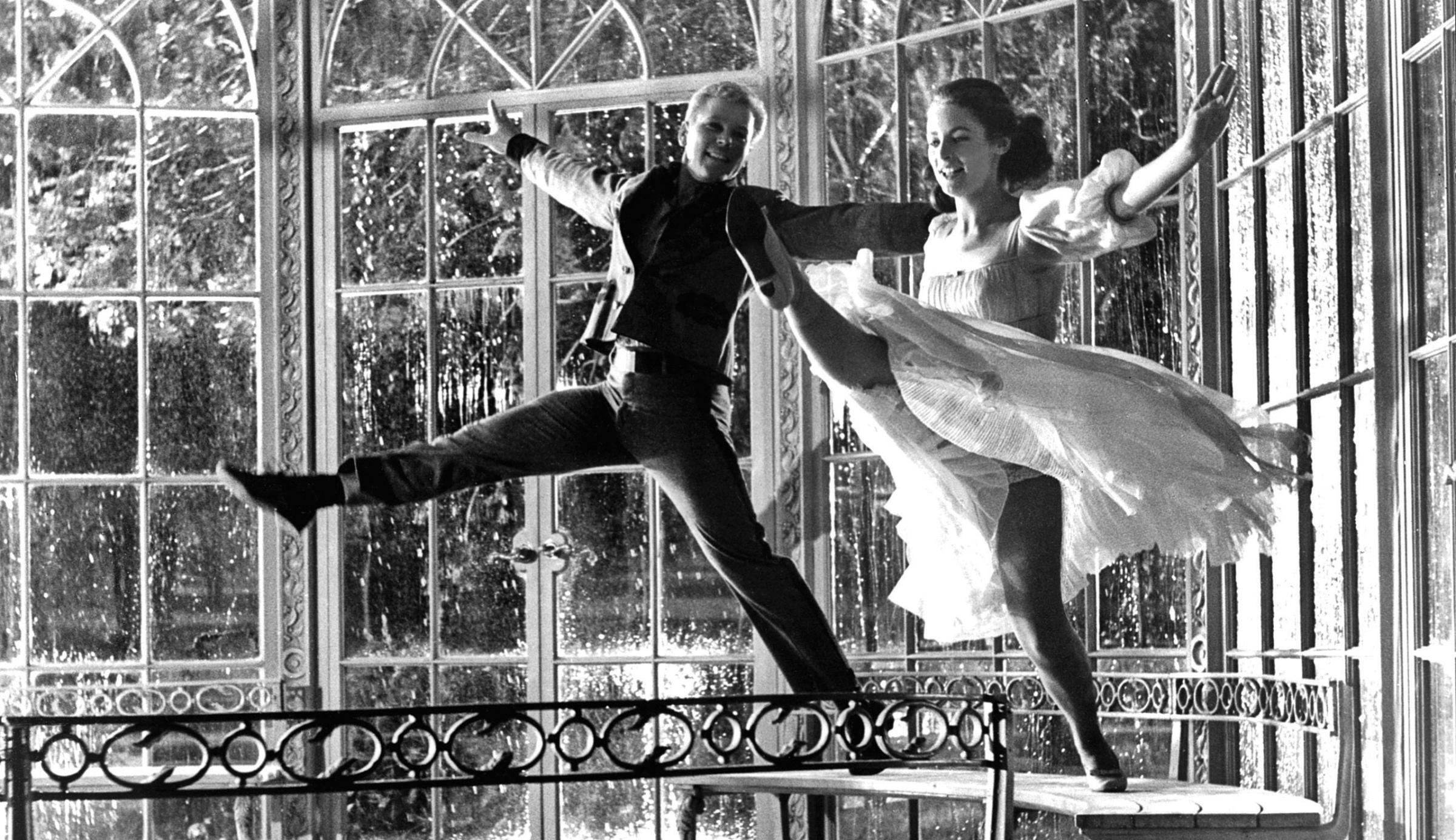

In the R&H version, the orphan Maria is first attracted to convent life because of the nuns’ religious chorales she hears. Then she brings singing, which to her is the highest form of bliss, to the von Trapps. One song (“Do Re Mi”) instructs the children in the seductive algebra of melody; another (“My Favorite Things”) calms their fears in a thunderstorm. Georg comes to admire Maria when he hears a song she has taught the children and, like Fred Astaire in his ’30s musicals with Ginger Rogers, falls in love with her as they dance. A singing performance by the children helps Georg activate his escape plan; and the movie ends with the family crosses the Austrian border with a heavenly choir intoning the title tune.

TURNING THE MUSICAL INTO A MOVIE

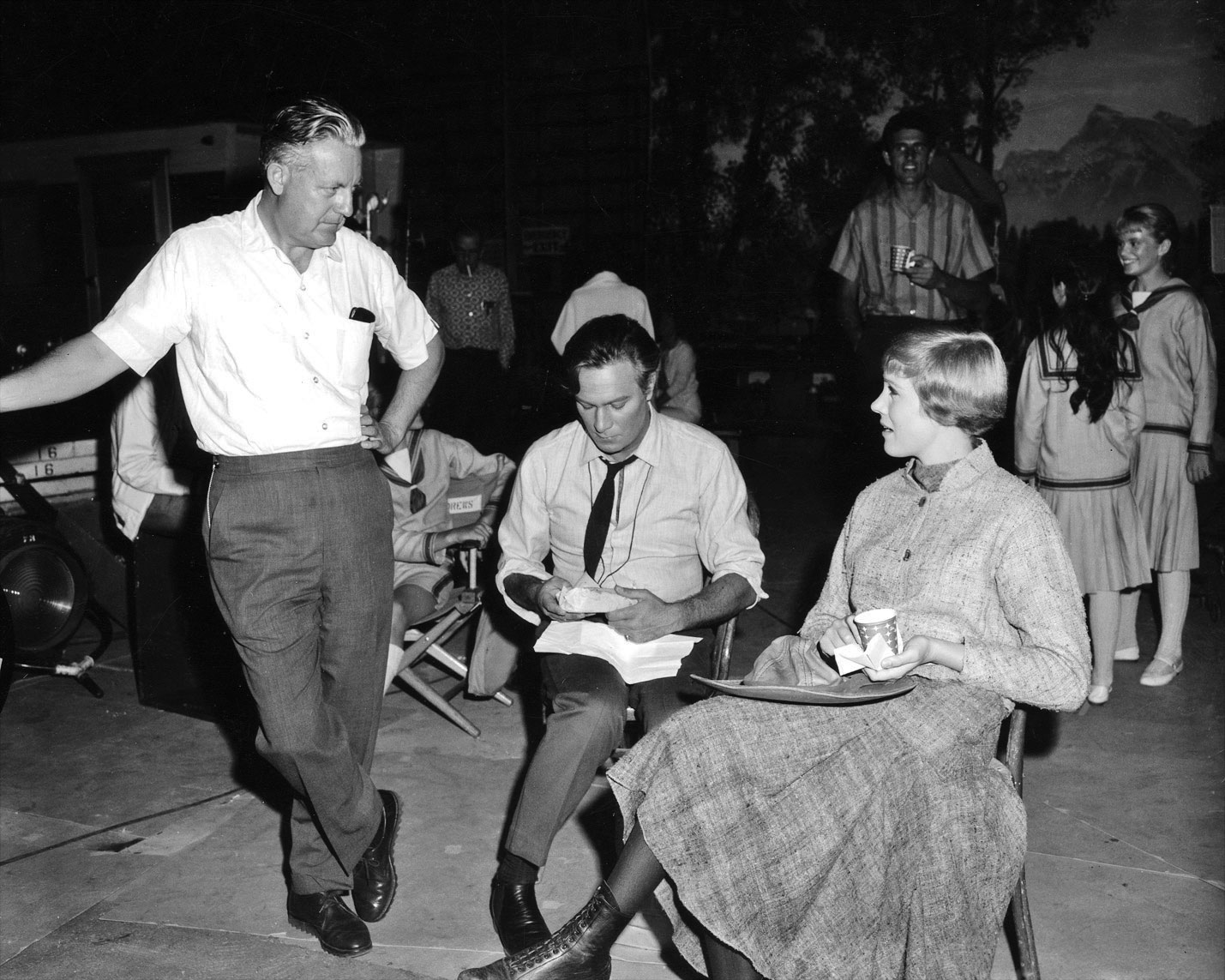

Somehow, this natural movie project took ages to come to fruition. Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, co-directors of the great movie musical Singin’ in the Rain, separately turned down the chance to direct The Sound of Music. George Roy Hill, who would later direct Andrews in Hawaii and Thoroughly Modern Millie, said no. So did Vincent J. Donehue, director of the Broadway version, and Wise, who was busy preparing his war epic The Sand Pebbles. Three-time Oscar laureate William Wyler finally agreed, and worked on the film’s preproduction, before realizing his heart wasn’t in it. When the Sand Pebbles shooting was delayed, Wise took over, backing into the job of producer-director on the most popular musical in Hollywood history.

The movie’s great good luck was the casting of Andrews. A Broadway comer at 19 with The Boy Friend and a precocious star at 21 as Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady, she also played and sang the title role in Cinderella, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1957 TV musical. Bizarrely, in the first decade of her stage radiance she didn’t make a movie, and lost the Eliza role to Audrey Hepburn for the film version. But she was a smash in her movie debut, Mary Poppins, winning the Best Actress Oscar; Hepburn was not even nominated. Seeing Andrews as the Disney nanny, Wyler knew he had found his Maria. And then, it is said, she initially declined the role.

On Broadway, the 45-year-old Martin had been paired with the Captain Georg of Theodore Bikel, 10 years her junior. But movies, even fanciful musicals, demand a hint of casting verisimilitude; and Andrews, 29 when she filmed The Sound of Music, was picture-perfect plausible as the girlish Maria, and possessed a vocal range far beyond Martin’s standard Broadway soprano. She and Plummer, then a mature 35, made a fetching match in the opposites-attract romance. Should anyone be reckless enough to imagine a remake, we can think of two modern movie-star equivalents: Amy Adams, whose stint in a 2012 Shakespeare in the Park staging of Into the Woods showcased her singing talent, and who could easily channel Andrews’ chipper chirpiness; and Michael Fassbender, the Irish star who is a dead ringer for the youngish Plummer.

A handsome Canadian who had won acclaim in Shakespearean roles, Plummer famously resisted the spirit of the enterprise, which he treasonously renamed “The Sound of Mucus.” He admitted that he was drunk during the filming of the climactic sequence at the music festival, and compared working with the affable Andrews to “being hit on the head with a big Valentine’s Day card, every day.”

Yet as much as Plummer may have enjoyed playing the tarantula on the movie’s rich strudel, he’s a pro who gives an admirably performance, balancing Andrews’ comic high notes in the early going with his own repressed poignancy. His Captain is a man whose soul died when his wife did, and whose warmer feelings have turned to cinders. Because she brought music to the family, he forbids it now; to him, every child’s melody has the sound of an obscene dirge for the love he lost.

In the movie’s strongest sequence, the Captain has brought the wealthy baroness (Eleanor Parker), with whom he plans a marriage of social and financial convenience, to the family home. Aghast to find his kids climbing trees in fatigues Maria has sewn out of drapes, he upbraids the girl for her impudence. She parries by saying that the children are miserable because he has withdrawn from them; and as he tells her she’s fired, the sound of “The Sound of Music” in perfect seven-part harmony reaches his ears and touches his heart.

In perhaps the speediest emotional conversion in cinema history, the Captain springs to life, like a trampled flower reblooming, to accompany his singing septet in the final phrase, “And I’ll sing once more.” He tells Maria, “You brought music back into the house” — the music that he always associated with his late wife. Cured of his grief, he must marry the new musicmaker. At the 2hr.12min. mark of this 2hr.54min. movie, Georg and Maria kiss. The nanny diary is at last a love story.

For the movie, Rodgers wrote a number that he and Hammerstein hadn’t thought of for the show: a love song for Maria and the Captain, “Something Good.” (It’s wan but welcome.) The filmmakers’ rule seems to have been that, if characters aren’t wonderful, they don’t get to sing. So both of the Baroness’s numbers with Max Detweiler (Richard Haydn), the comic relief and Trapp family impresario, were cut. Nuns sing but Nazis don’t, except in a Mel Brooks musical; they march. As the movie darkens with the German Anschluss and the Trapps’ plan to flee Austria, the pace accelerates. A brief fight, a gunshot, a quick trip across the Alps, a choral reprise of “Climb Ev’ry Mountain,” and the movie is over. You hardly have a chance to wipe the tears away before the houselights come up.

Today’s movies rarely provide that stirring catharsis. In an era of Marvel superheroes with personality disorders, and when the few megahit heroines are warrior princesses — Katniss of The Hunger Games — the notion of a would-be nun outwitting the Nazis with the weapon of melody is so old-fashioned it’s almost radical. Based in fact, this is the purest domestic fantasy: the story of a woman who learns to love a man by falling in love with his children and, in the process, repairs a broken family.

It’s a fairy tale told and sung at bedtime by the sweetest mother. And 50 years after its release, that fable has a nurturing impact. For millions of viewers, the thrills are alive with The Sound of Music.

This essay appears, in slightly different form, in The Sound of Music: 50 Years Later, the Hills Are Still Alive, a special edition of LIFE, available on newsstands everywhere.

Read TIME’s original review of the film of The Sound of Music, here in the archives: R-H Positive

"The Sound of Music" at 50: The Hills Are Still Alive

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com