Neal Shapiro was there in 2004 when Tom Brokaw left the anchor chair of NBC Nightly News to Brian Williams.

Having spent 35 years in television news, Shapiro has worked nearby most every prominent newsreader in the business. He has seen reporters rise and seen them fall. And he has seen the fallen find ways to get up again.

“I think TV and America love second acts,” the former president of NBC News says. “I think whatever issues some reporters have in their past, there’s a long history of people reinventing themselves.”

Williams is scuffling now, caught in a tale of misremembered facts and embellished details. In fact, Shapiro was reflecting recently on the chances of recovery for a different NBC veteran, one who, like Williams, has found himself on the wrong end of tabloid attention. Now this other longtime network personality is seeking a second chance of his own.

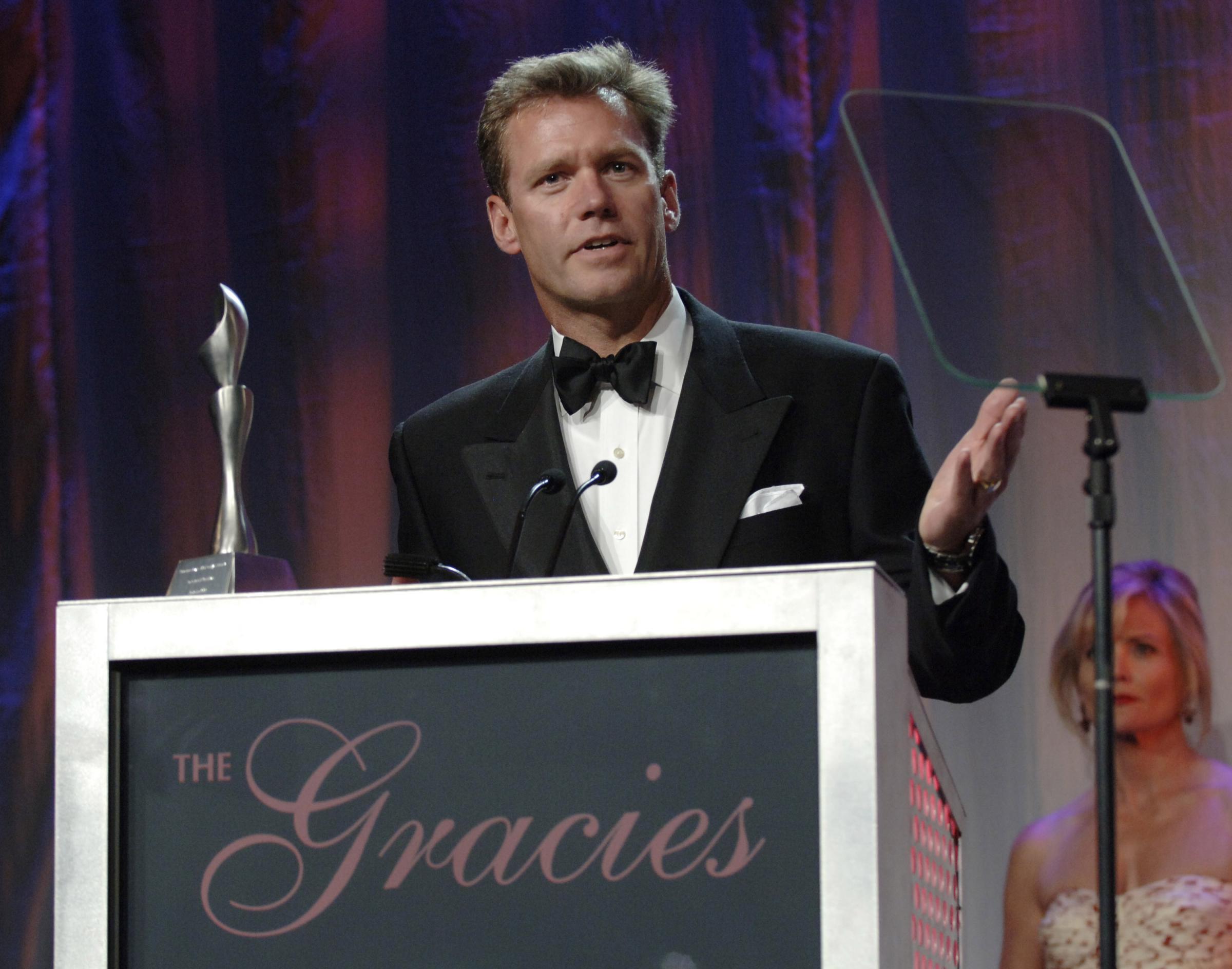

Chris Hansen is returning to television. To trace the length of that comeback, you need to go back eight years to a grey afternoon in Terrell, Texas. There, inside a single-story home, an important state prosecutor named Louis Conradt raised a Browning .380 pistol to his head. In front of police and near Hansen’s cameras, Conradt shot himself dead.

Since 2004, the television newsmagazine Dateline NBC had aired an enterprising segment called To Catch a Predator, a sting operation that exposed dozens of men, including Conradt, and arrested would-be child sex offenders. As host of the hidden-camera series, Hansen became a star journalist and one of the most recognizable faces at NBC News, right alongside Williams.

The prosecutor’s suicide was shocking, and it became the first in a series of events that pushed Hansen from television. Conradt’s sister filed a $105 million lawsuit against NBC, and though it was settled out of court, many felt the case led the network to pull the plug on Predator for good in 2007.

'I think TV and America love second acts.'

As Hansen spun off the series into other hidden-camera segments for the network, reports surfaced that made the journalist himself the story. The married Hansen was allegedly having an affair with a Florida television reporter some 20 years his junior. In 2013, the woman, who said employers would no longer hire her after news broke of her apparent relationship with Hansen, released personal photos of herself and Hansen, including one showing what appeared to be the couple locked in a kiss. A short while later, NBC announced it was not renewing Hansen’s contract.

NBC, which would not comment on the circumstances surrounding Hansen’s departure, was quick to scrub most mentions of him from its website, and soon Hansen’s own Twitter feed had dried up, too. He tried his hand at a couple of pilots, but nothing got off the ground. It began to look like Hansen was less of a free agent than a newsman in exile.

Then a breakthrough came last summer. Hansen met with executives at the true-crime cable channel Investigation Discovery, and by the fall an original show, Killer Instinct with Chris Hansen, had been greenlit. The show will begin its 10-episode run later this year (five episodes have already been shot). Staying relevant during the move from network to cable is no small order—ask Dan Rather or Conan O’Brien about it—but for Hansen it will be a shot at redemption. Now Hansen speaks out for the first time since leaving NBC.

***

Late last year, Hansen found himself in a Texas prison facing a killer convicted of what the journalist says was a “horrendous murder.” Hansen had spent the fall and winter bouncing around the country conducting interviews for Killer Instinct. The show will give Hansen a platform once again to do what he says he does best. “It [will] involve people speaking out for the first time,” Hansen says, “and my ability to sometimes get these people to talk who had never talked before.”

Hansen wishes to discuss his new show rather than say much about his private life, but as someone who’s traded in stories his entire career he is well aware viewers and media observers will be keeping close watch. For Investigation Discovery, Hansen will shed many of the hidden-camera tricks he used at NBC. Instead of popping out at subjects dressed as a homeless person or confronting unsuspecting pedophiles, Hansen will revisit true-crime stories that have not yet been widely investigated.

As an interviewer, Hansen still ranks. He excels in getting subjects to open up, and to do so in detail, about matters they might not otherwise be inclined to discuss. His polished voice and delivery reveal themselves today even in casual conversation. Executives at Investigation Discovery say the decision to bring Hansen on despite rumors of his personal life and a messy split with NBC was not a difficult one. “It didn’t give us a moment of hesitation,” says Kevin Bennett, the channel’s general manager.

Hansen leapt into journalism with the same certainty. He lived in Chicago until he was eight, when Hansen’s father, who worked in sales for the Eaton Corporation, received a promotion. The family picked up and settled in the exclusive Bloomfield Township near Detroit. It was there, in the summer of 1975, that the infamous labor union leader Jimmy Hoffa went missing. It was widely believed that Hoffa had been the victim of a mob hit, and his disappearance became a sensational news story. Network reporters arrived from New York City, and Hansen would ride his bike to the crime scene a mile-and-a-half from home to watch the FBI comb for clues. It was then journalism struck him.

“From that moment on, this is all I really wanted to do,” Hansen says. “It was the excitement that this major event had happened, although tragic, and that I could go watch it. It was all Detroit was talking about.”

Hansen began reporting as a student at Michigan State University, and later for local stations in Tampa and Detroit. By 1991, Hansen received his first offer from NBC. The network wondered if Hansen might be interested in moving to London to become a correspondent, and while budget cuts surrounding the Gulf War wiped the network chance away, it did not do so for good. Two years later, Hansen was called to New York to appear on a new NBC program starring Brokaw and Katie Couric, and in 1994 he joined the staff of Dateline NBC.

His sons first considered him a celebrity when he was parodied on an episode of 'South Park.'

It was on Dateline, Hansen stretched his legs as a TV journalist. Take any major news story of the previous two decades—there is a good chance he covered it. Hansen was there for the Unabomber, Columbine and the impeachment of President Bill Clinton. In 1995, after the bombings in Oklahoma City, NBC rented out a hardware store as a makeshift studio, and one night Hansen stood on the roof overlooking the rubble where 168 people were killed. Hansen told himself, “I will never see anything as tragic as this in my entire lifetime.” Six years later, he was in Manhattan reporting on Sept. 11.

Hansen won eight Emmy Awards for investigative reporting at NBC, but his career truly took off in 2004 when he pitched the story that would become To Catch a Predator. The segments were extremely popular, pulling in more than 10 million viewers at their height in 2006, and Hansen was now regularly getting stopped on the street, having his picture taken at airports. His sons first considered him a celebrity when he was parodied on South Park.

***

As much as Predator was a hit, it was a magnet for controversy too. In the segments, decoys, posing as underage boys or girls, chatted online with adult men, many of whom would agree to visit offline for what they believed would be sex with a minor. Instead, they arrived at a home rigged by NBC with cameras and microphones. Hansen presented them with chat logs in which they had solicited sex with boys and girls so young the age difference had to measured in decades, not years, and the alleged predators would take off running.

Hansen and those behind Predator have long insisted decoys never initiated chat-room conversations or were the first to bring up sex. But detractors of the segments argued its decoys were manipulative, baiting men into escalating their fantasies to reality.

'I think we exposed a lot of bad people...if the old guard journalists have a problem with that, then so be it.'

Sometimes, while they did not set off a dialogue about sex, the decoys would insist the men meet in real life. During one sting, a female decoy hired by NBC seemed to beg an alleged predator to visit, even offering to pay for the gas needed to drive there. In the case of Conradt, 56, who believed he was chatting with a 13-year-old boy, the decoy appeared to grow desperate when the prosecutor said he could not come over because his sister was visiting. According to their chat transcripts, one instant message sent then to Conradt read: “Ditch her!”

Today, Hansen rebuffs critics who say the segments amounted to civilians and TV producers masquerading as law enforcement. “I think we raised awareness and created a dialogue that didn’t exist before,” he says. “We created compelling television, and I think we exposed a lot of bad people who were preying on children. So if the old-guard journalists have a problem with that, then so be it.”

Conradt’s suicide rattled Hansen and his NBC crew, but it did not immediately finish Predator. (The legal settlement between Conradt’s family and the network prevents Hansen and those involved with the case from talking about it publicly.) Advertiser discomfort is the likeliest cause for the series’ cancellation. By 2007, companies began to pull their sponsorship of the segments, wary of having their products associated with the program’s content. Privately, one former NBC executive says that Predator, a once-fresh idea, had been overexposed and beaten into the ground by the network.

Predator has left a difficult legacy, although it does not trouble its host. Hansen believes the segments ended simply because they had run their course. To the show’s star, that Predator was bought and syndicated across the world for years following its original run was proof its criticisms were overblown. “At the end of the day,” he says, “we had proved our point.”

Buoyed by his Predator success, Hansen starred in subsequent spin-off projects at NBC, including segments titled “To Catch a Con Man” and “To Catch an ID Thief.” His style of reporting had become a trademark: He was the man with the hidden camera, outing people who thought they’d never be exposed. Yet between 2011 and 2013, Hansen himself saw his private life become the subject of public consumption.

Hansen declined to comment on his alleged affair, as did the other reporter named in the stories. “If NBC were upset about it or thought there was some moral lapse that impacted my ability to do my job, they could have exercised the morals clause in my contract three years ago,” Hansen says. “And that never happened.”

Hansen, who has two sons and lives in Connecticut, is certain his departure from NBC was amicable. He felt, as the network apparently agreed, Dateline was moving away from his particular brand of investigative journalism.

Killer Instinct will be Hansen’s shot to seize back the spotlight he once held. Each episode, Hansen says, will roll out like a feature film. “It’s a different look, it’s a different feel,” he says. “I sort of feel like I’m on the cutting edge of something.”

Hansen is also back where he started, reporting on the types of stories that drew him to journalism in the first place. On Killer Instinct, the episodes will succeed or fail based on Hansen’s ability to get people to talk. The series will be, Hansen says, “tailored around my way of doing interviews.”

Once more, Hansen will be putting himself at the center of the story.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the year Tom Brokaw left NBC Nightly News. It was 2004.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com