A federal judge in Texas became the latest supporting player to take center stage in the nation’s ongoing immigration drama. But for U.S. District Judge Andrew S. Hanen, the southern border with Mexico has always played a starring role.

On Monday night, Hanen ordered the Obama Administration to stop a plan to defer deportations for up to 5 million people who are in the U.S. illegally while a lawsuit filed by 26 states plays out in the courts. The order drew praise from many Republicans as well as criticism from opponents who quickly cast him as a “staunch critic” of the president’s immigration policy.

“[The deferred deportation program] does not represent mere inadequacy; it is complete abdication,” Hanen wrote. “The [Department of Homeland Security] does have discretion in the manner in which it chooses to fulfill the expressed will of Congress. It cannot, however, enact a program whereby it not only ignores the dictates of Congress, but actively acts to thwart them.”

Hanen is no stranger to the issues involved. For the last 12 years, the problems that have occupied not only the Rio Grande Valley, but the wider nation — drug trafficking, political corruption, border disputes and now, immigration — have been center stage in his South Texas courtroom. Hanen, an appointee of George W. Bush, has presided over high profile racketeering trials involving state and local officials, sat in judgment on a parade of smuggling and drug cases, and ridden herd over eminent domain lawsuits prompted by the federal government’s desire to build a fence along the Texas-Mexico border.

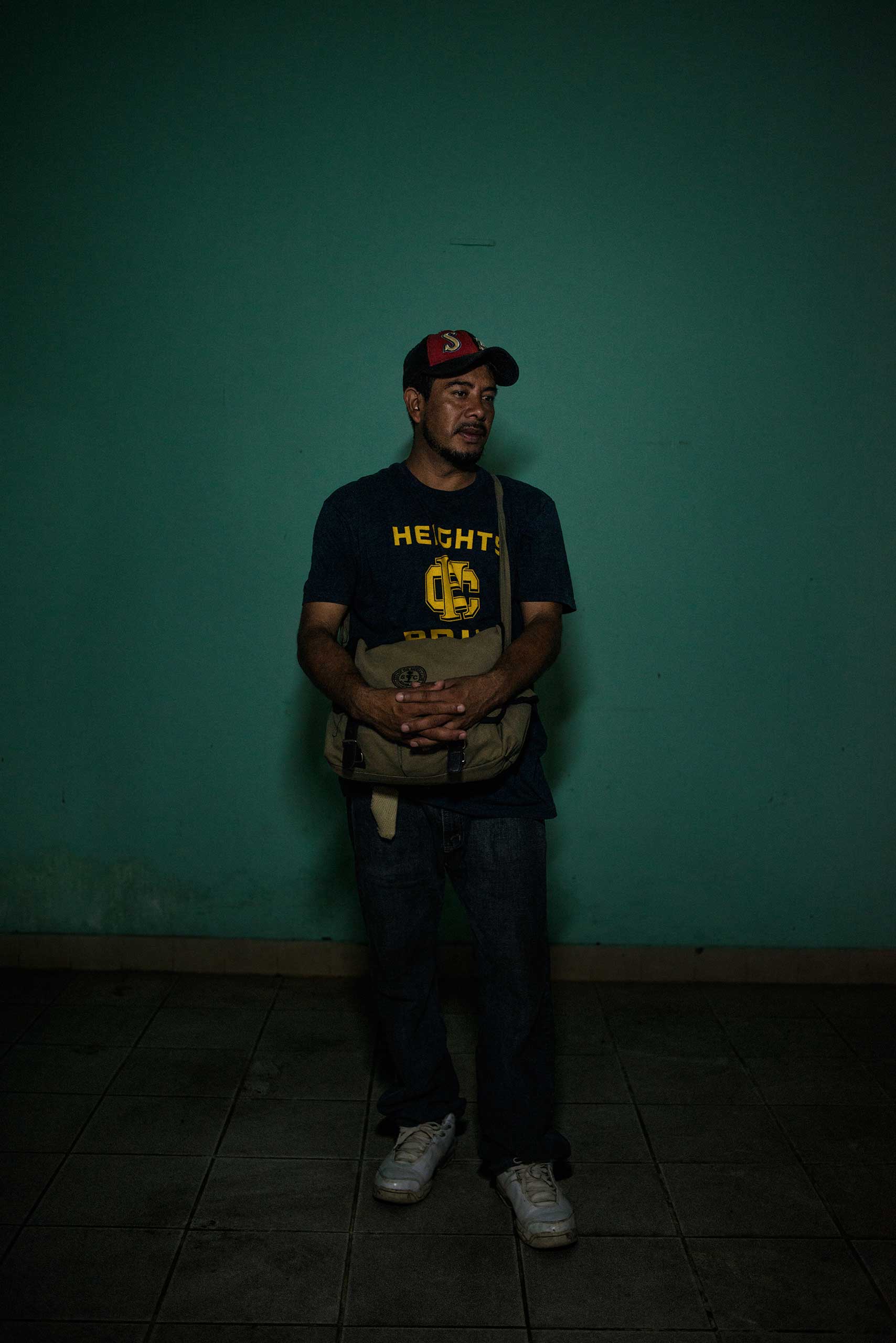

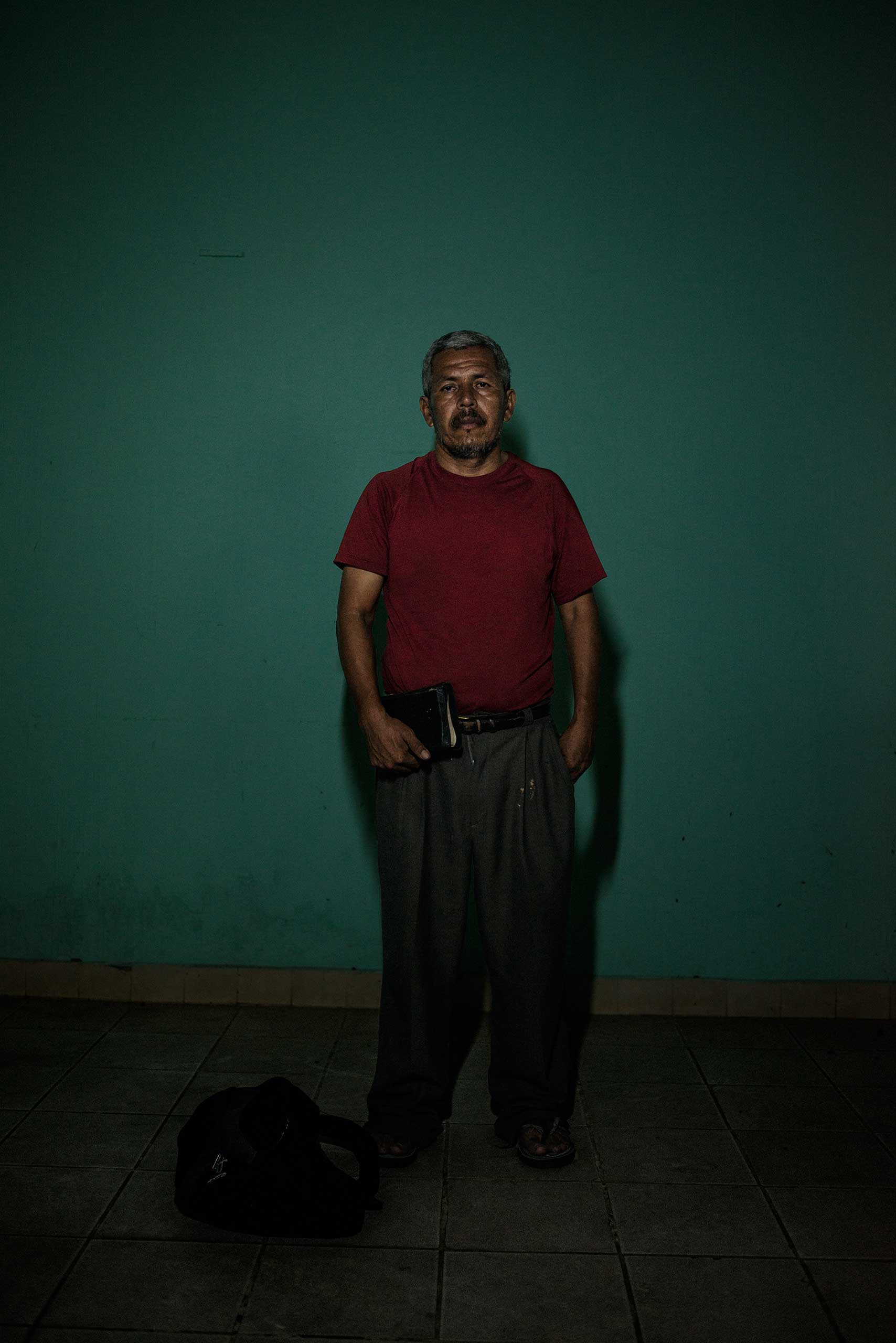

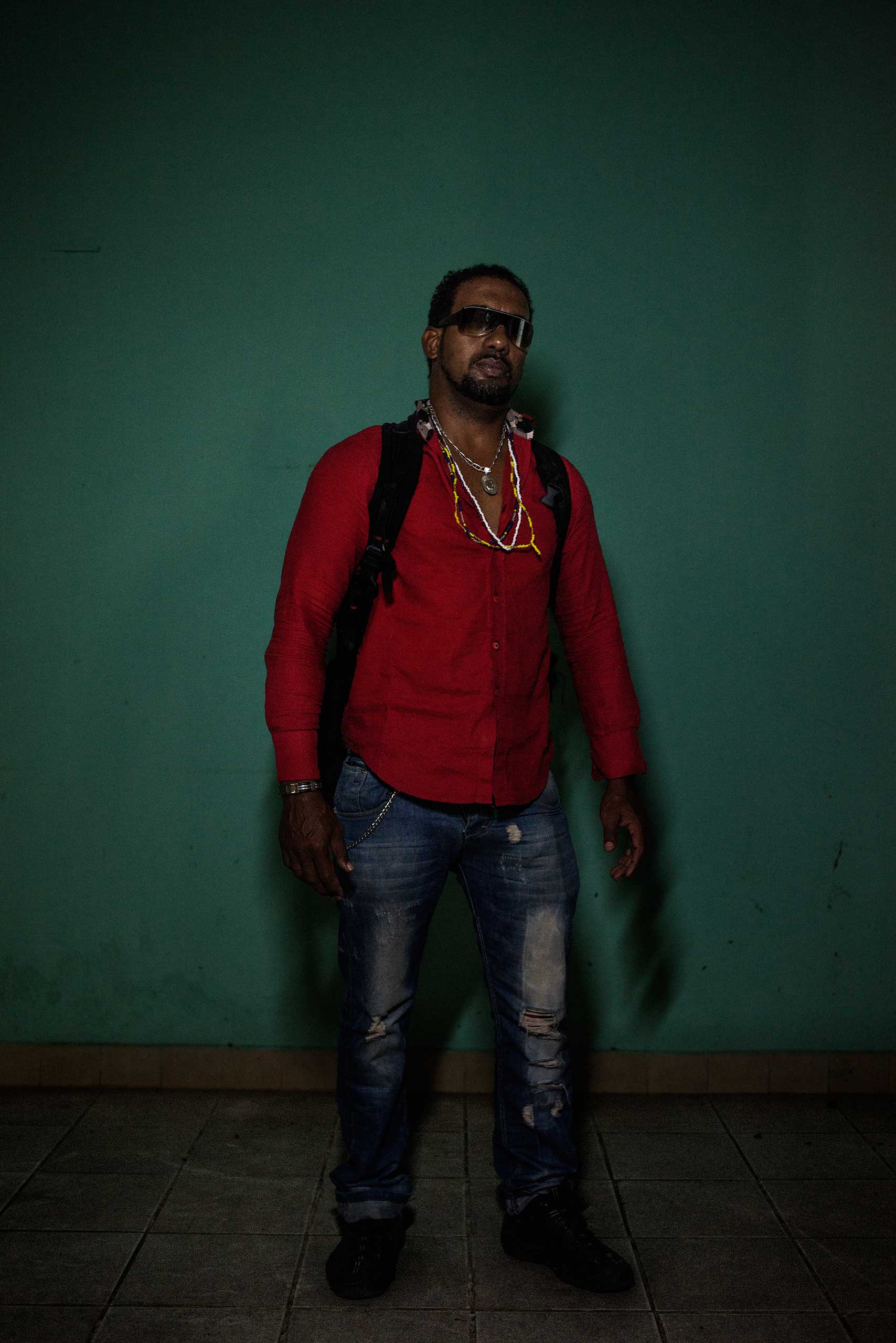

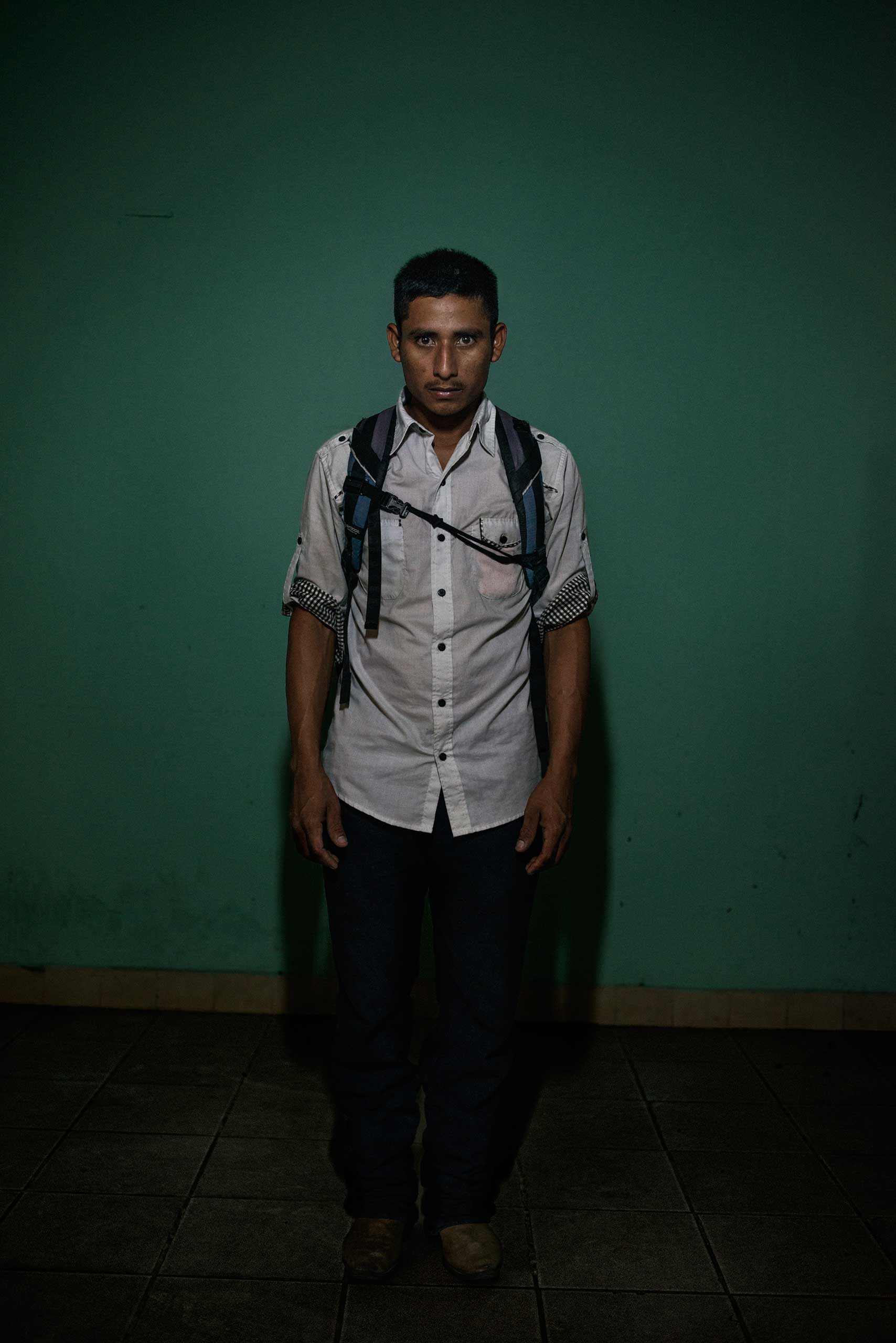

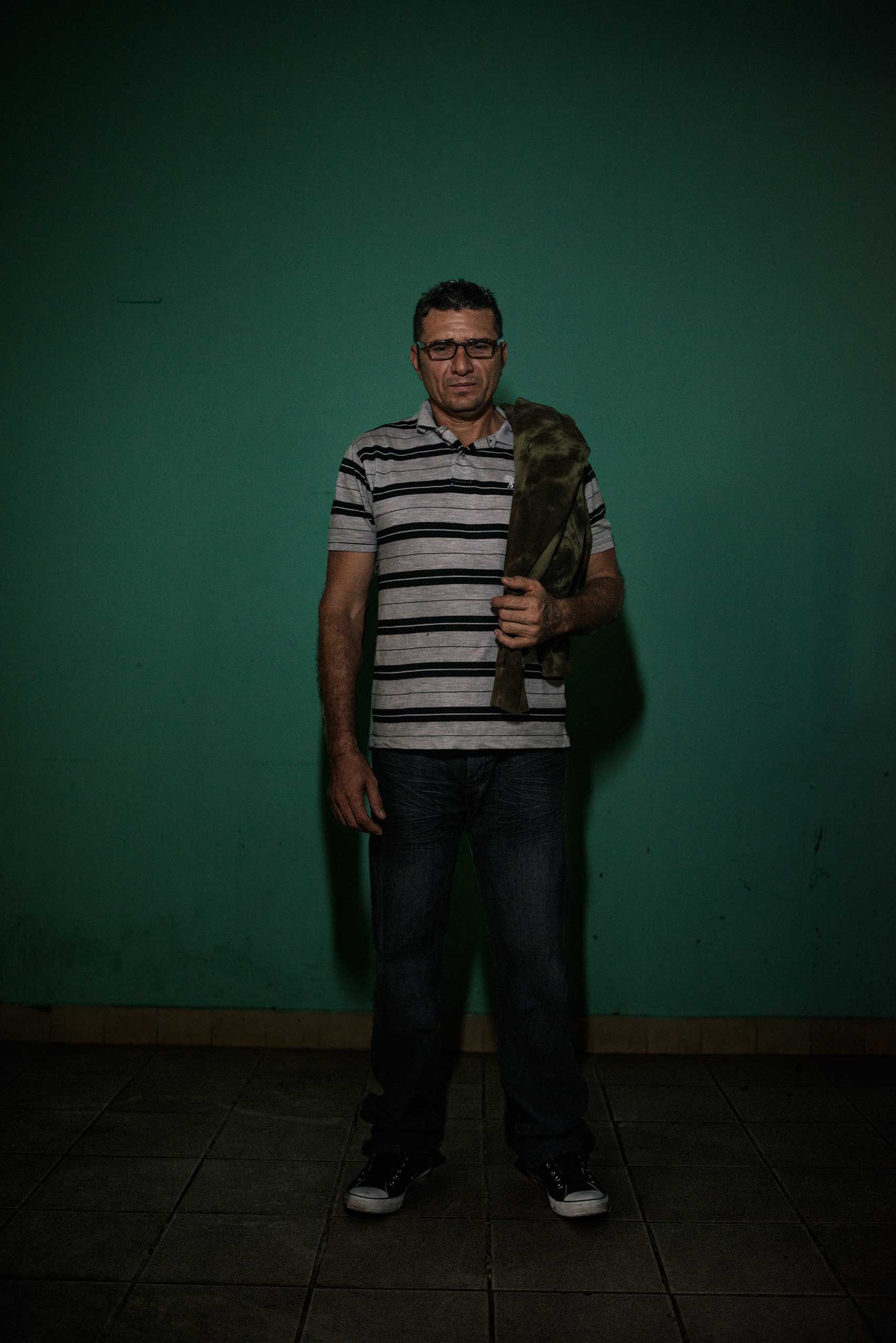

Photos: Documenting Immigration From Both Sides of the Border

Attorneys who have practiced in his court told Texas Lawyer on Tuesday that Hanen, who was a respected civil litigation attorney with one of Houston’s establishment law firms before becoming a federal judge in 2002, is a well-liked conservative with a libertarian streak.

The tumult paraded into Hanen’s Brownsville courtroom is a far cry from the hushed, lush surroundings of his early career. After graduating first in his class at Baylor Law School in 1978, Hanen, known to friends as “Andy,” went to work as a briefing clerk for one of the most esteemed figures in Texas judicial history, Chief Justice Joe Greenhill, the longest-serving justice on the Texas Supreme Court. Greenhill was a Democrat, but then so were the overwhelming majority of officeholders and Texas leading lawyers in those days. The two became close enough that Hanen was one of the speakers at Greenhill’s memorial service in 2011. After a year of clerking, Hanen joined Andrews Kurth, a powerful Houston-based firm whose alumni include former U.S. Secretary of State and Bush family consigliere James Baker.

Hanen began donating to Republican candidates in the 1990s, contributing small sums to U.S. Senator Phil Gramm. In 1992, President George H.W. Bush nominated him to the federal bench, but he was never confirmed. The younger Bush tried again with more success; in May, 2002, Hanen was confirmed to the bench of the U.S. District Court of the Southern District of Texas by a 97-0 Senate vote.

Since then, close observers say Hanen’s tenure has often been marked by a concern for signs of government overreach. “Sure, he’s a conservative, but he also has what might be called a libertarian bent, certainly with regards to property rights,” says Terence M. Garrett, a professor of government at the University of Texas, Brownsville.

In 2008, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security filed hundreds of eminent domain lawsuits in an effort to build the fence along the U.S.-Mexico border. Hanen has traveled to many of the disputed properties to look over the land and examine issues like access to water rights along the river. In January, Texas Lawyer noted Hanen had the most unresolved cases, some 136, on his docket in the district, thanks, in large part, to the DHS cases.

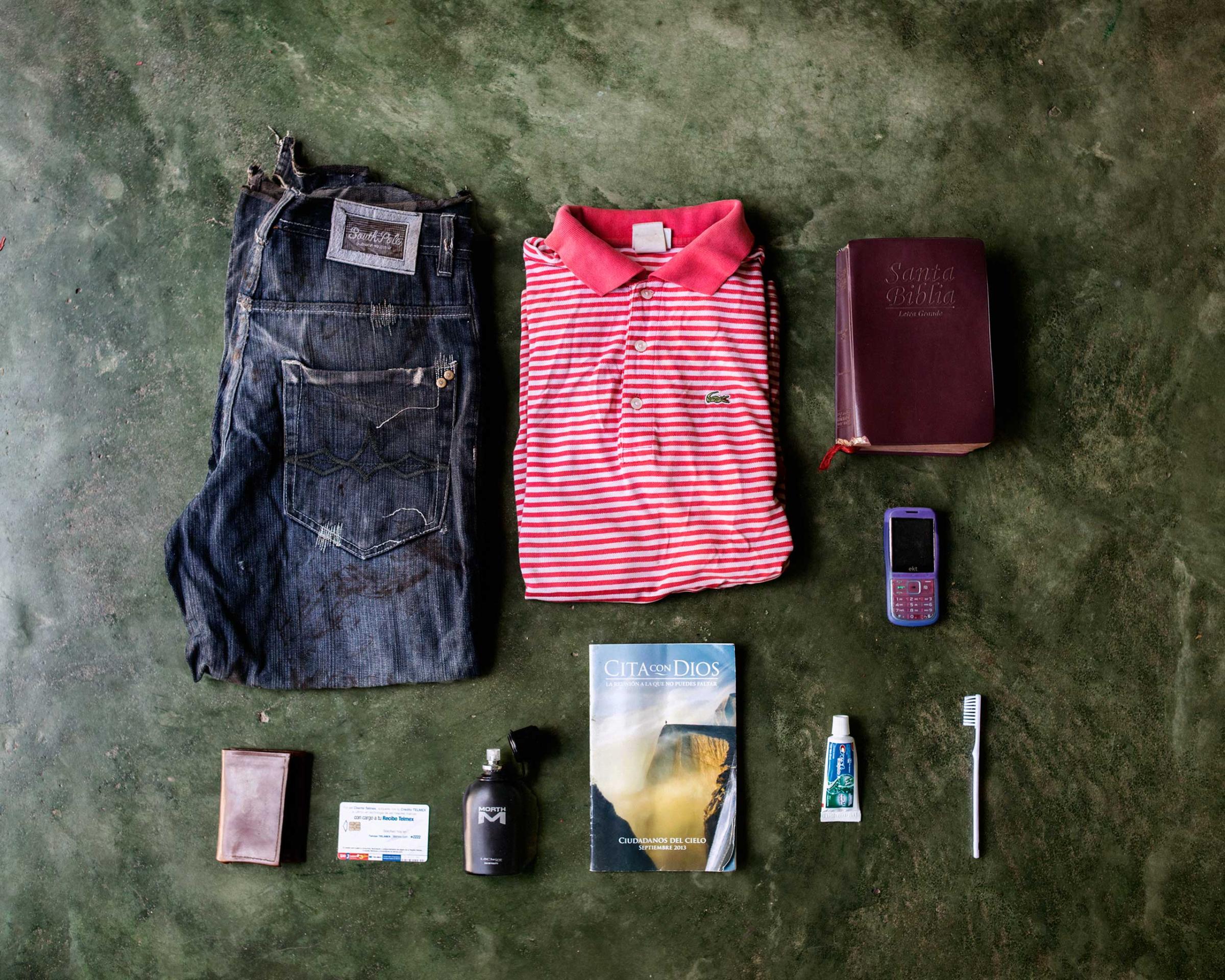

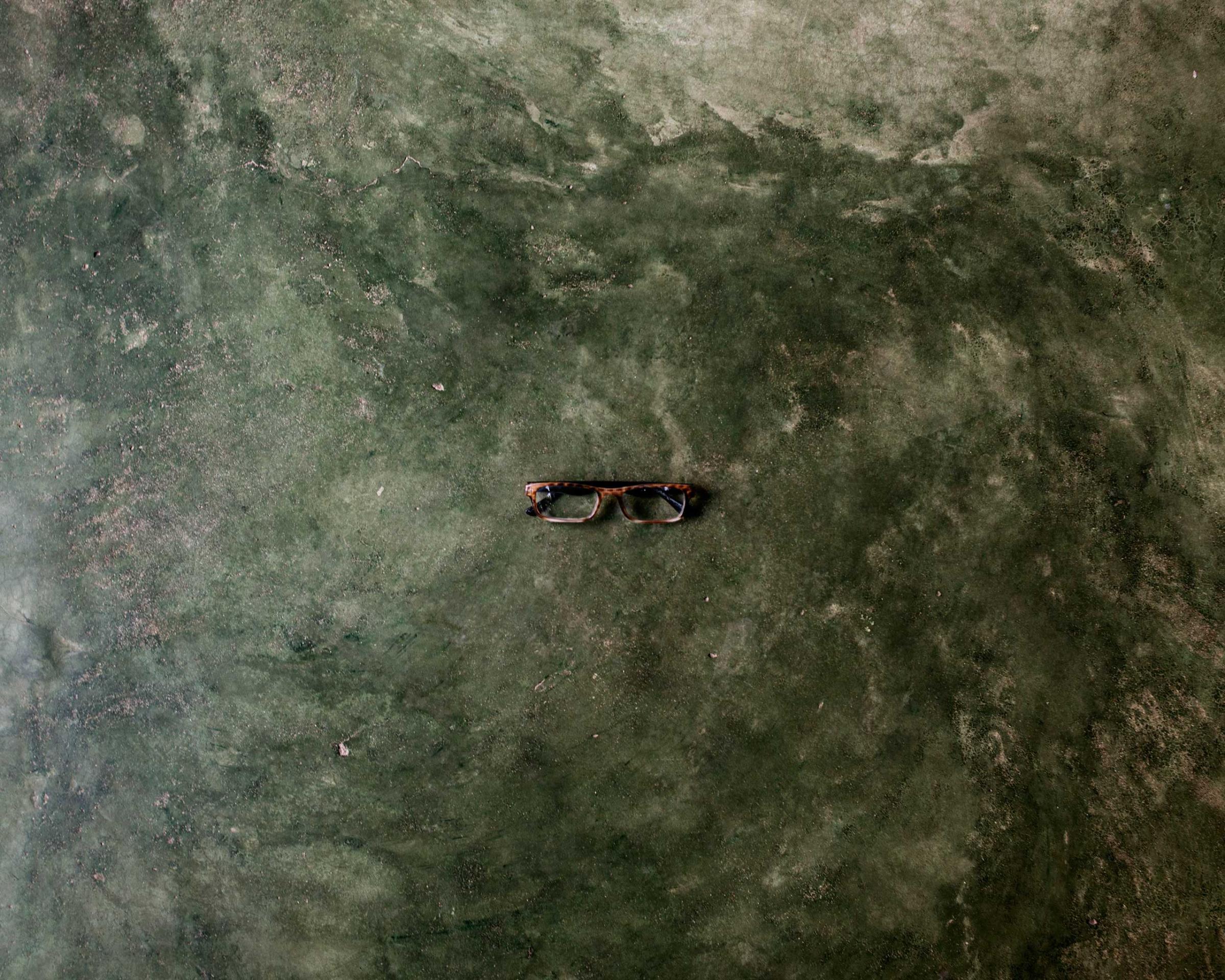

See What Illegal Immigrants Carry in Their Bags

In some of the cases, Garrett says, Hanen’s rulings slowed the agency’s rush to build the fence which, he adds, was an unpopular undertaking among Valley residents from both sides of the political fence. “He caused DHS to at least respect the law,” Garrett says. Hanen told Texas Lawyer he could move the cases along faster by ordering the landowners into court, but he had chosen not to: “The added problem is, as a judge, you could force these things to trial, but it’s not fair to the land owner. … To make them go to trial with a lawyer when they are in the midst of negotiating with the government would cost them more than they will ever receive.”

The realities of life in South Texas also have spilled over into other cases before Hanen, prompting him to castigate federal authorities in a California immigration case for releasing a Salvadoran felon convicted in his court, and criticizing DHS for what he characterized as completing the act of smuggling by reuniting children from Central America with parents in the U.S. illegally.

Those earlier rulings prompted supporters of President Obama’s immigration plan to charge the 26 states attorneys general suing to stop it were judge-shopping when they filed in Brownsville. Hanen responded by implying that his proximity to the border made him particularly well-suited to understand the stakes. “Talking to anyone in Brownsville about immigration is like talking to Noah about the flood,” he said in January.

Indeed, U.S. Border Patrol statistics illustrate the wave of arrivals. In fiscal year 2014, some 256,393 individuals crossed into the Rio Grande Valley sector in which Hanen works, accounting for 52.6% the total crossings along the entire southern border. From Oct. 1, 2014, to Jan. 31, 2015, some 6,434 “unaccompanied alien children” crossed in the Rio Grande Valley sector, down a little from the 7,198 in the same period a year earlier, but still the largest number along the southwest border running from Brownsville to Yuma, Ariz. And the Rio Grande Valley sector has the most drug smuggling cases and the second-most immigration cases involving abuse and other associated felonies, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

Still, not all of the judge’s focus is on the border. In 2013, Hanen sentenced a state district judge, a state representative, a local district attorney and several plaintiffs’ attorneys to prison in a large racketeering scheme. Joel Androphy, a Houston defense attorney who has known Hanen since they were both active in the Houston Bar Association, represented one of the convicted.

“He’s not looking to become famous, he’s looking to do the right thing,” Androphy told Texas Lawyer, adding that he might not agree with him, but “I would trust his judgment.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com