If past years’ ratings are any indication, some 12 million Americans will tune in Monday night to the premiere of Season 8 of The Voice. Though American Idol has lost some of its luster through its 14 seasons and The X Factor’s ratings are on the decline, the TV-watching public is stuck on these shows like white on Ryan Seacrest’s teeth.

Long before Simon Cowell was a twinkle in his father’s eye, the Kelly Clarksons and Carrie Underwoods of the day were introduced to America by a man named Arthur Godfrey. Like The Voice, in which coaches can hear but not see competitors as they audition, Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts relied on the aural above the visual—it was, after all, a radio show.

When LIFE profiled Godfrey in 1948, his voice was ubiquitous on the American airwaves, reaching 40 million listeners each week. “By refusing to shut up while other entertainers are enjoying a late morning’s sleep or rehearsing their next week’s shows” Ernest Havemann wrote, “he has built just about the biggest audience of anybody on the air.”

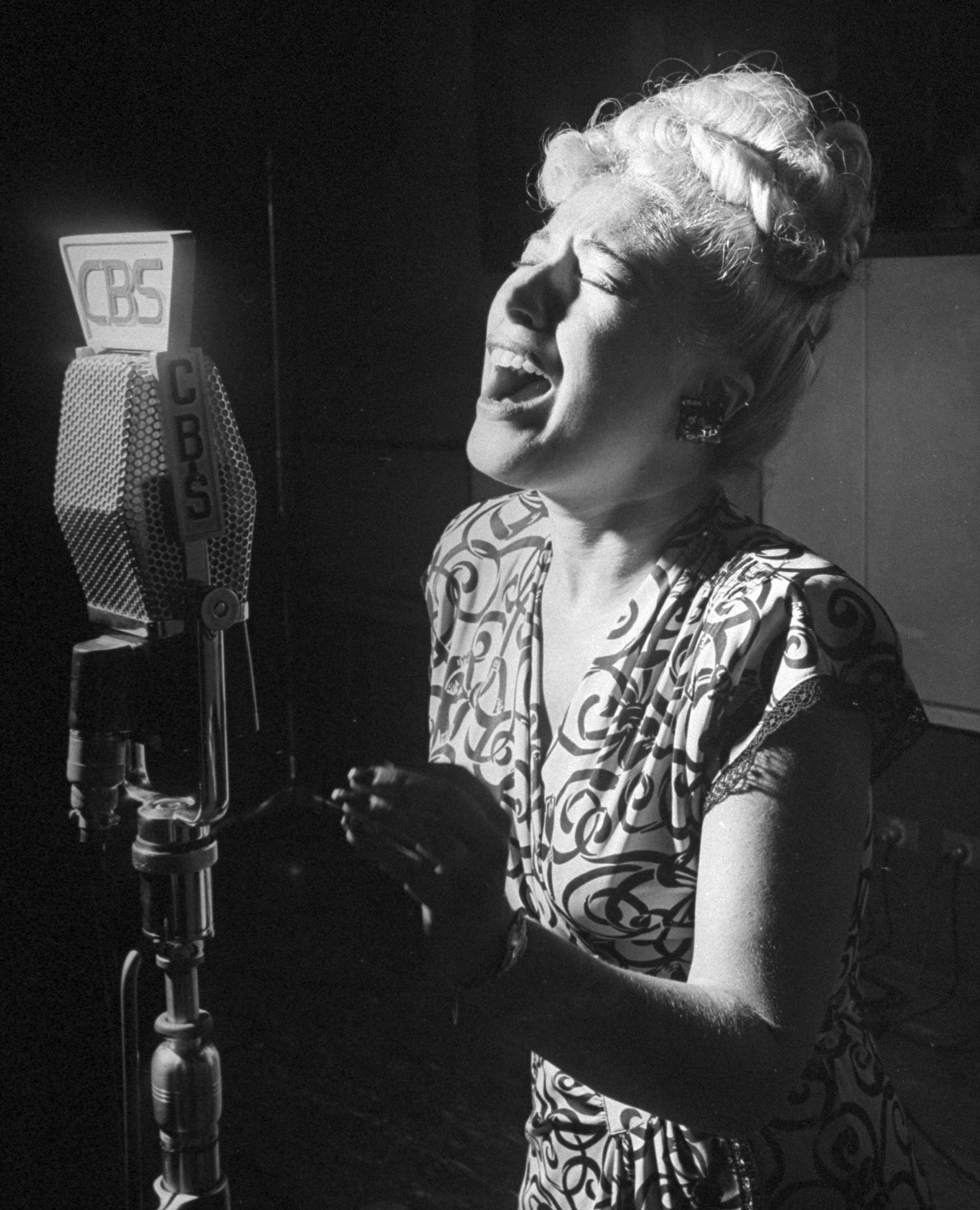

Talent Scouts, “a sort of amateur hour for young professionals,” ran for 25 minutes on Monday nights with the sponsorship of Lipton tea. During the show, the “scouts”—who could be anyone from a manager to a parent—brought out their “talent” to perform in front of a live audience. Winners were decided by an old-fashioned applause meter, with a new star declared each night as opposed to the current model of waiting until the end of the season.

“He will probably be on television very shortly,” LIFE predicted, and the prophecy soon came true: After two years on the radio, Talent Scouts became a regular show on CBS, requiring no changes other than allowing cameras into the studio Godfrey already occupied. The show reached number one in the Nielsen ratings during the 1951-52 season, and remained a top program until it ended in 1958.

In addition to emceeing, Godfrey offered input on decisions like wardrobe and song choice. Diahann Carroll, who debuted on the show as a teenager, said in an interview that “he had something to say about almost everything.” When Patsy Cline appeared in 1957 ready to perform “A Poor Man’s Roses” in a cowgirl outfit her mother had sewn for her, Godfrey advised her to ditch the country duds for a cocktail dress. He suggested she sing “Walkin’ After Midnight” instead. And after ten years of performing without a big break, Cline’s star was finally born.

Godfrey had a couple of misses during his years judging talent. He passed over a certain hip-gyrating Mississippi kid, for one thing. Mr. Presley, no worse for the rejection, would find his break somewhere else.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com