All across Liberia, streets are filled with the excited laughter of children returning to school after a six-month hiatus. The children, decked in the smart cotton uniforms of both public and private schools, line up in front of their classrooms to wash their hands in chlorine solution and wait to get their temperatures read by teachers wielding infrared thermometer guns.

Once inside they will pick up lessons abandoned in August, when an Ebola epidemic cut a swath through the country, infecting nearly 9,000 and killing at least 3,826. “The Ebola outbreak has had a devastating effect on our health and education systems and our way of life in Liberia,” Liberia’s Minister of Education Etmonia Tarpeh said in a statement. “We have managed to beat back the spread of the virus through collective efforts. Reopening and getting our children back to school is an important aspect of ensuring children’s education is not further interrupted.”

Ebola taught the nation to fear contact, to avoid unnecessary gatherings and to distrust a government and an international community that seemed both unwilling and unable to bring the crisis to an end. But with the start of school — deemed safe by the Ministry of Education, even though the virus has not been completely eradicated from the country — Liberians are regaining a sense of normalcy and can allow themselves to hope for a time when Ebola is little more than a bad memory. “It’s a good sign,” says school nurse Iris Martor. “We can’t let down our guard, but we can start thinking about the future again.”

Life Returns to Normal After Deadly Ebola Outbreak

Not all schools have opened. Some have yet to receive basic sanitation kits from the government and the U.N. Children’s Fund, and others are still being cleaned up and disinfected after having served as holding centers for the ill. Some, like Martor’s More Than Me Academy, which serves underprivileged girls from Monrovia’s West Point slum, won’t open their doors until March 2.

Schools have already reopened in neighboring Guinea, where the outbreak started in late 2013, and are expected to open in Sierra Leone, which has seen the highest number of infections, at the end of March. Of the three most affected countries, Liberia has recovered the quickest. It has seen just a handful of new cases every week since January, compared with an increase from 39 to 65 new cases in Guinea and 76 new cases in Sierra Leone in the week ending Feb. 8, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Still, it’s a dramatic decline compared with the hundreds of new cases every week during the peak of the epidemic in September and October.

On Monday, officials in the three countries announced that they had set a target of reducing the number of new cases to zero within 60 days. It is an achievable goal, but similar targets have been set in the past, only to be undermined by a sudden flare-up in unexpected areas.

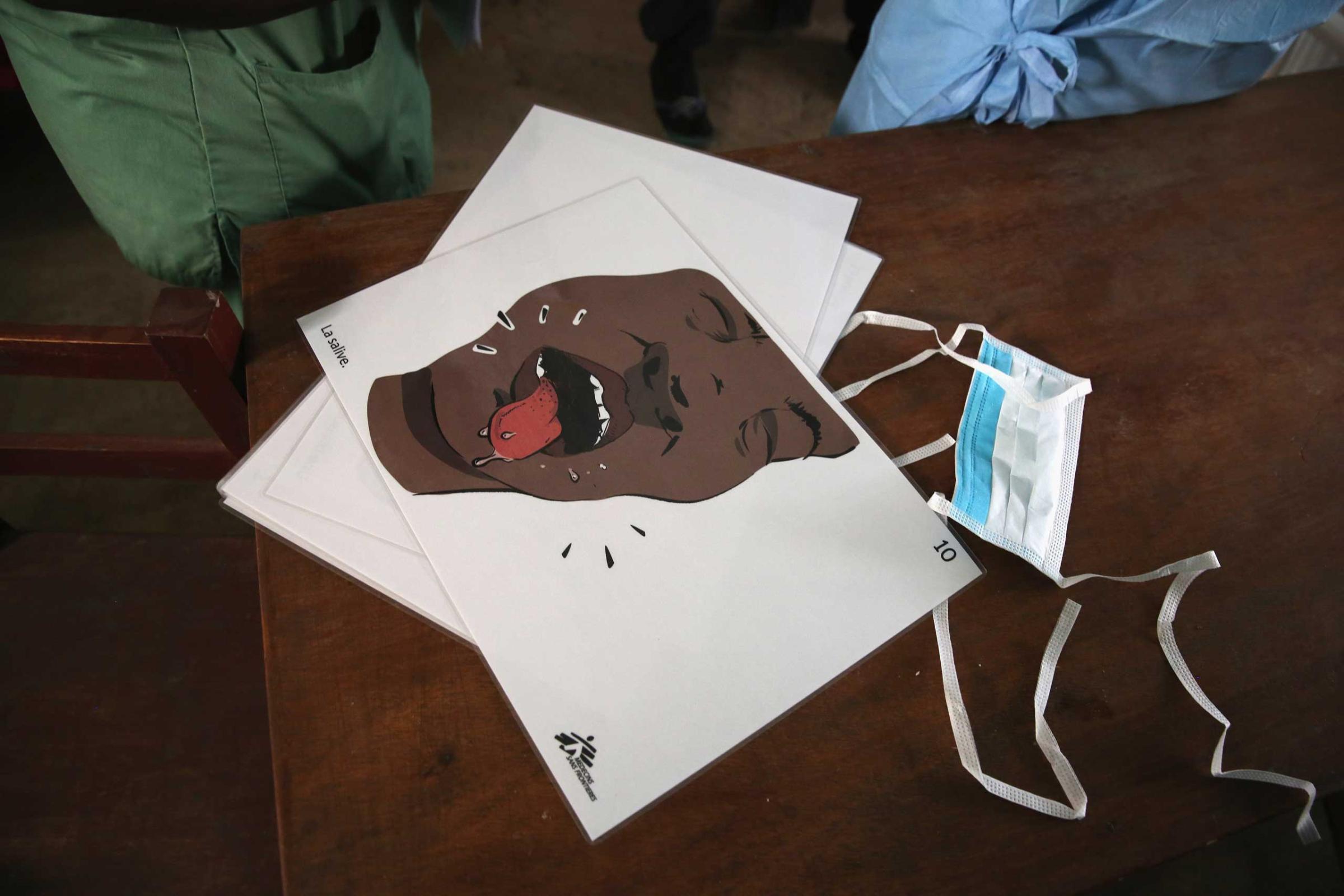

Ebola, which kills nearly half its victims, is spread through contact with infected bodily fluids. Practices like the washing of the dead are deeply ingrained in West African society; all it takes is one improperly conducted funeral for a new chain of transmission to start, undermining weeks of work. The WHO, in its most recent assessment, noted that Guinea reported a total of 34 unsafe burials last week.

Elsewhere in the country, village mobs attacked health workers from the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders, accusing them of bringing the virus. Sierra Leone was forced to quarantine a fishing community in the capital, Freetown, after the discovery of a cluster of five new cases. “We are very, very far from the end of the outbreak,” Iza Ciglenecki from Doctors Without Borders told reporters at a science conference in California on Saturday. For most illnesses, it is enough to get the number of cases down to a low rate for doctors to be satisfied they have an infectious disease under control. Not so for Ebola. Until the number of new cases stays at zero for 42 days — twice the maximum incubation period — no one can afford to let their guard down, not even the students washing their hands in chlorine in the schoolyard.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com