When The Feminine Mystique hit bookstores on Feb. 19, 1963, more than a few readers dismissed author Betty Friedan’s claims as dangerous. “If most mothers followed her advice, divorce and juvenile delinquency would increase tremendously,” read one letter to the editors at LIFE. “By the time American women have been indoctrinated by Betty Freidan and Simone de Beauvoir, they’re ready to commit mass suicide,” read another.

To these readers, Friedan’s identification of “the problem that has no name”—the elusive sadness of housewives whose lives revolved around vacuums and burp cloths rather than self-actualization—represented a threat to the social order. To Friedan, it was long past time to name the source of so many women’s unhappiness so that steps could be taken to address it.

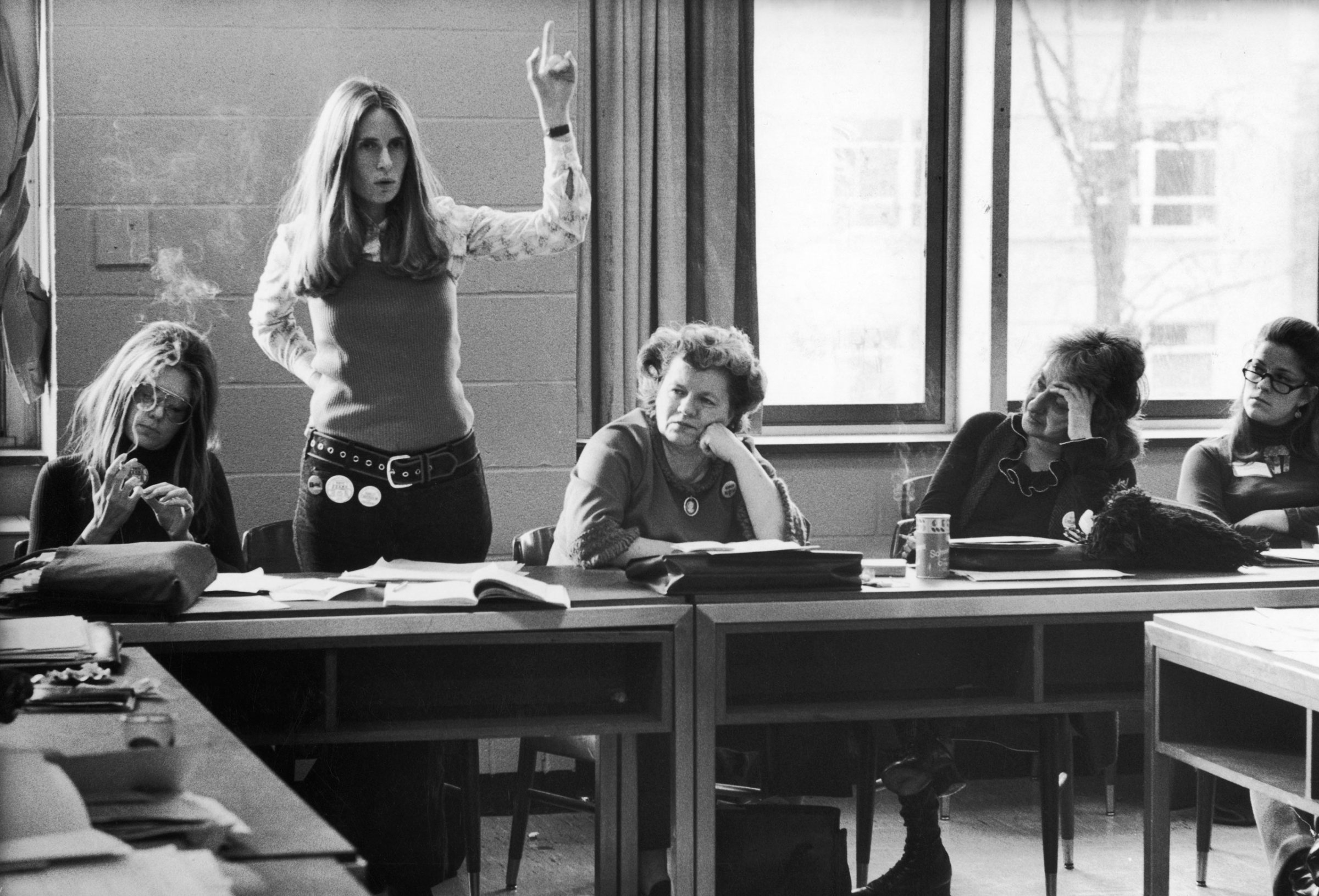

The words “anger” and “angry” appear frequently in reviews and reactions published in response to the book. LIFE called Friedan an “Angry Battler for Her Sex,” and the book, “an angry, thoroughly documented book that in one way or another is going to provoke the daylights out of almost everyone who reads it.”

While it’s tempting to write off these characterizations as dismissals of the author as hysterical or unserious, Friedan herself owned that anger. It was one of the many forces—along with a desire to reframe the guilt so many mothers and housewives felt about wanting more–that drove her to write the book in the first place.

In an interview with LIFE in November 1963, after the book had been marinating in the minds of the American public for six months, Friedan took the opportunity to respond to her critics, many of them women. She called out those who saw the book as a call to action they weren’t prepared to take:

I guess a lot of women don’t like my book because they feel threatened by it. Perhaps it’s because they don’t take themselves seriously, won’t work to the limit of their ability. For them it’s easier—they can always say what a great actress or writer they could have been if only they’d kept at it, but of course they gave it up to make a home. They don’t subject themselves to the decisions and actions it takes to get started.

She identified what she deemed an insecurity among working women who took issue with the book:

Capital C Career Women seem to resent my book, maybe because I say that all women should try to do what the Career Women are already doing. Maybe they’re finding they’re not so special. Maybe they don’t want others muscling into the act.

To the men who jokingly lamented an equivalent “masculine mystique”:

Masculine mystique? Sure there’ve been a lot of jokes. My husband was the first to crack one. There’s some truth in it. Why should men be all that strong? This man’s-world-woman’s-world bit is for the birds. Men aren’t barred from growing as women are. Yet men are victims of the feminine mystique too because it keeps them from knowing women as human beings.

To those who believed subscribing to her worldview required a gargantuan effort and guaranteed a miserable, sexless existence:

You don’t have to choose a joyless celibacy if you want to use your brain. You needn’t make huge decisions, you have to make the right little ones—like studying for the exam instead of going to the movies and writing in the morning instead of getting an early start for the beach.

Dismantling the feminine mystique, Friedan said, need not begin as an international movement. It could—and should—begin in the very same home that cultivated the mystique in the first place. “You have nothing to lose,” she reassured skeptics, “but your vacuum cleaners.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com