The Imitation Game director Morten Tyldum is still surprised by how little he knew about the movie’s subject, Alan Turing, before taking on the project. “It’s sort of like if Albert Einstein was a little-known mathematician,” he says. “Alan Turing was one of the most important individuals in the last century, and he’d sort of been living in the shadows of history far too long. I think it’s impossible to not be fascinated or intrigued or outraged when you hear the story for the first time.”

Though The Imitation Game (like other some of the other biopics that stand a chance to win an Oscar this weekend) has come under fire for historical inaccuracies and not delving deeply enough into Alan Turing’s sexuality, the Oscar-nominated director says that emotional accuracy was very important to him while making the film. Though he left some of the best odd details he learned about Turing out of the film—”He was allergic to pollen, so he used to wear a gasmask sometimes in meetings without telling anybody why,” for example—Tyldum says the overall arc of the film is true to Turing’s life.

He spoke with TIME about the true story of Turing’s sexuality, suicide and odd habits.

TIME: How much do you think historical accuracy matters in a biopic?

Morten Tyldum: I think it matters a lot. It’s a huge responsibility when you’re dealing with real-life persons and real-life events to do it accurately. Of course, you have to compress a lot into two hours, and there’s no way you can be totally accurate. You have to convey the emotional accuracy—how did Alan Turing feel at this time?—and to do that, you sort of have to dramatize events.

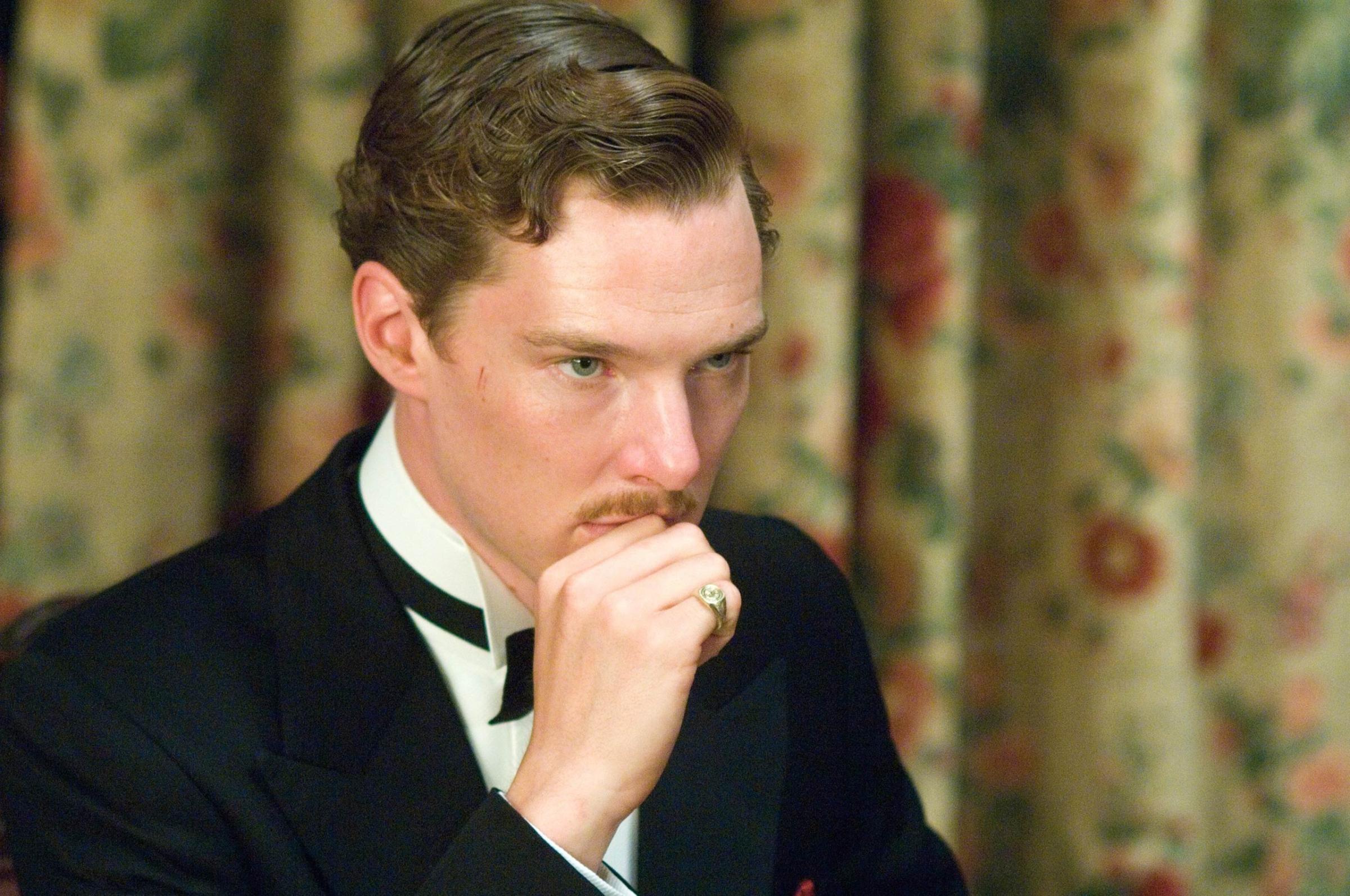

That’s why I wanted it to feel like a thriller. He was 27 years old when he came to Bletchley [Park, where the code-breakers worked]. Here was this man plucked straight out of Cambridge. And he ends up with all these incredible secrets being dumped on his shoulders and all this incredible pressure. It would be as if he was living in the middle of this wartime spy thriller, so that’s what we wanted to convey.

One thing people have been saying is it’s not accurate that the machine he built was named Christopher. Here’s the fact though: The machine was inspired by Christopher. We know this because he wrote letters to Christopher’s mom his whole life. We know that from his journals, his obsession about recreating a consciousness that he lost—Christopher. How do we communicate that onscreen without making it a lecture? By naming the machine Christopher.

Could you talk a little bit about the effort that went into re-creating all the details in the computer?

It’s based on the machine he built. It’s this incredible design with all of these colorful dials in red and yellow—that’s how it was. We also wanted to emphasize that it was more than a machine for Alan. So we added all this red cabling that was sort of like the blood veins of something that is alive.

Turing eventually went through chemical castration and then committed suicide. Do you know what happened to the other men prosecuted under this law?

I think prison was more common than chemical castration. What I do know is that this law had a huge impact on many male lives. I got a very touching email from a 92-year-old man who said, ‘I was wrongfully convicted by the same law as Alan Turing when I was young and thank you for shedding a light on this. I watched your movie in tears.’

Fifty thousand men are still alive who were prosecuted under this law. This law existed up until 1967. Can you imagine? And it was only for men, not women. It was known as the blackmail law because people had something on you they could use against you. That’s why the campaign is going on that all the 50,000 men who have been convicted should all be pardoned. Because there’s nothing to forgive, nothing to pardon. They never did anything wrong.

Why did you decide not to show Alan Turing’s suicide?

We shot Benedict being dead, and in many ways it felt melodramatic and unnecessary. To me, it’s all about his relationship to Christopher. So him turning off the light on the machine and saying goodbye to Christopher, then the movie is over.

At first, we were fascinated by the apple. Alan killed himself by taking a bite of this cyanide apple, and the rumor was that that’s where the Apple logo came from. It was this great link from the inventor of computer science to this device we all carry around in our pockets now. I shot the apple and Benedict lying there and all that. But the whole thing turned into a sort of Apple commercial. The other thing is, it turns out it’s not really true. Steve Jobs said he wished Alan Turing had been the inspiration for the Apple logo, but it was a coincidence.

The apple did come from Alan Turing’s fascination with Snow White, which we tried to get in but there wasn’t room for it. It was too hard to explain. The true story is actually that he watched Snow White when he was waiting for the interview with Commander Denniston at Bletchley Park—the one that you see in the beginning of the film. He took the train from London, and he was early and went to the village cinema to see a movie while he was waiting. He saw Snow White, and from then on, he was a little obsessed with the story of Snow White. That’s why he decided to kill himself with the bite of an apple—which is in many ways poetic, but it felt like too much to explain.

I wanted to show the last night they had together, which is also a true story, they made this huge bonfire and burned everything. I wanted to go from his goodbye to Christopher to that ending with the fire. It just felt right.

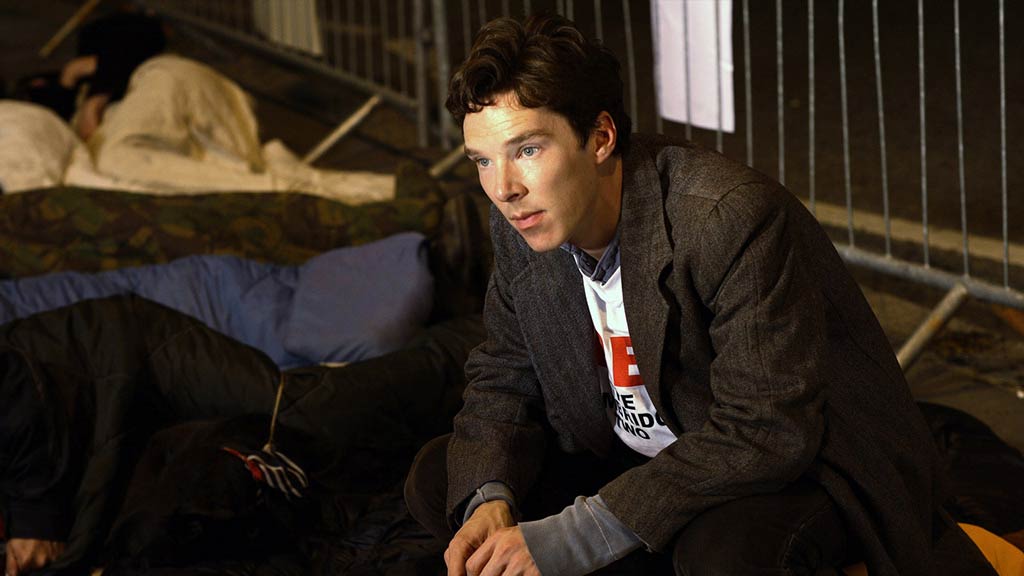

Read next: Benedict Cumberbatch Talks About Playing the Role of the Genius

Benedict Cumberbatch Roles You Didn’t Know About

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com and Diane Tsai at diane.tsai@time.com