Social Media can be an effective tool for a president wanting to stay in touch with his citizens. It can also be a potent, and public, amplifier of criticism, as South African President Jacob Zuma learned to his dismay this week. In advance of his annual State of the Nation address Zuma invited the public to suggest themes using the hashtag #SONA2015. The most tweeted topic? His resignation:

“Pay Back the Money” is likely to echo through the chambers of Parliament as well, when Zuma takes the stage on the evening of Feb. 12. For the past three years his office has been embroiled in the so-called “Nkandlagate” scandal, in which he has been charged with using $21 million in public funds to remodel his homestead in the rural town of Nkandla. The renovations were billed as “security upgrades” but included a private military hospital, a helicopter landing pad and the installation of a swimming pool. Zuma says that he was unaware of the improvements being made at his residence.

Zuma has avoided Parliament since August, when a rabble-rousing minority party, the Economic Freedom Fighters, heckled him from the stage with questions about when he would repay the money. The speaker of the house was forced to close down the question and answer period and eventually called in the police to subdue the wayward parliamentarians.

The EFF has vowed to repeat their performance at the State of the Nation address, raising fears that security will be called in once again, this time broadcast primetime on national television. South Africa’s Sunday Times newspaper reported that parliamentary security staff had been sent to self-defense classes in preparation for the address. (Parliamentary officials stated that the training was routine.) Meanwhile, the opposition Democratic Alliance has pitched a snit of its own, refusing to attend the traditional post-speech gala cocktail party on the grounds that at a cost of $382,000 it is a waste of taxpayer money. The deputy speaker of the National Assembly responded that he would bill the DA for empty seats, because it was too late to recoup the catering costs.

What would be a yawn-worthy event in any other circumstance has riveted the nation, says Frans Cronje, head of the Institute of Race Relations, South Africa’s oldest think-tank. “For the first time South Africans will watch the state of the nation address. This will beat anything else on TV.” One newspaper has even published rules for a drinking game to go with the speech. The pomp and pageantry of the annual address easily lends itself to ridicule. Complete with a red carpet, paparazzi and parliamentarians dressed to the nines (last year one minister showed up in a pilot’s uniform, even though he didn’t have a license), it is “the closest thing South Africa has to the Academy Awards,” says John Endres, CEO of the Johannesburg-based Good Governance Africa policy group.

But the circus-like atmosphere of this years’ address obscures some of the country’s deeper realities, few of which are likely to be covered in depth during the president’s speech. South Africa’s crippled power utility is struggling to meet demand after 20 years of neglect, resulting in rolling blackouts that are likely to last for several months. The power shortage has hobbled investment and curtailed growth in Africa’s most industrialized economy. On Tuesday the Rand fell to its weakest level in 13 years. While the overall unemployment rate decreased slightly last year, the country’s youth unemployment rate shot up to 52.6 percent, the highest in the continent, according to a new report by Good Governance Africa. “South Africa’s youth remain trapped, dependent on hand-outs and unable to improve their lives,” said Karen Hasse, a GGA researcher. “Without better education and business-friendly policies to encourage economic growth and employment, the country’s youth face a hopeless future.”

Zuma may touch on the power crisis and unemployment — it would be hard not to — but there is little he can do without fundamental policy changes, none of which appear forthcoming, says Cronje. “The government is running out of money to run the country. They can’t borrow any more because the debt to GDP ratio has doubled in five years, and they can’t reduce expenditures,” for fear of inciting unrest. Violent protests have become a near daily occurrence, over jobs, schooling, medical care and illegal immigrants. “For the first time since 1994 (the end of apartheid) we are seeing a real pick up in the hiring of riot control police officers.” The EFF spectacle in parliament is nothing compared to what South Africa has in store, he warns. “I wonder to what extent Zuma understands this or is interested in it. We are not seeing in his policies the types of moves that will draw investment to drive growth.”

Of course, state of the nation addresses are not where policy is made. In the case of South Africa, the occasion has become a platform for a populist party on the rise. “The EFF has nothing to lose,” says Enders, of Good Governance Africa. “They have been very smart at generating attention, and highlighting the weaknesses of the current system.” But what is good for the EFF, may not be so good for South Africa. “It’s a bit of a crisis, actually,” says Enders, speaking of the possibility that security forces may have to be called in if heckling gets out of hand. “Using the police to stop people from speaking in parliament is infringing on freedom of speech. But freedom of speech comes with rules that are meant to keep discourse civilized and allow the proper exchange of ideas. So what should be done if the EFF doesn’t follow those rules?” South Africa’s 2015 State of the Nation Address may be billed as spectacle, but it could turn into something much more serious.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the number of State of the Nation speeches Zuma has given. It is the 6th.

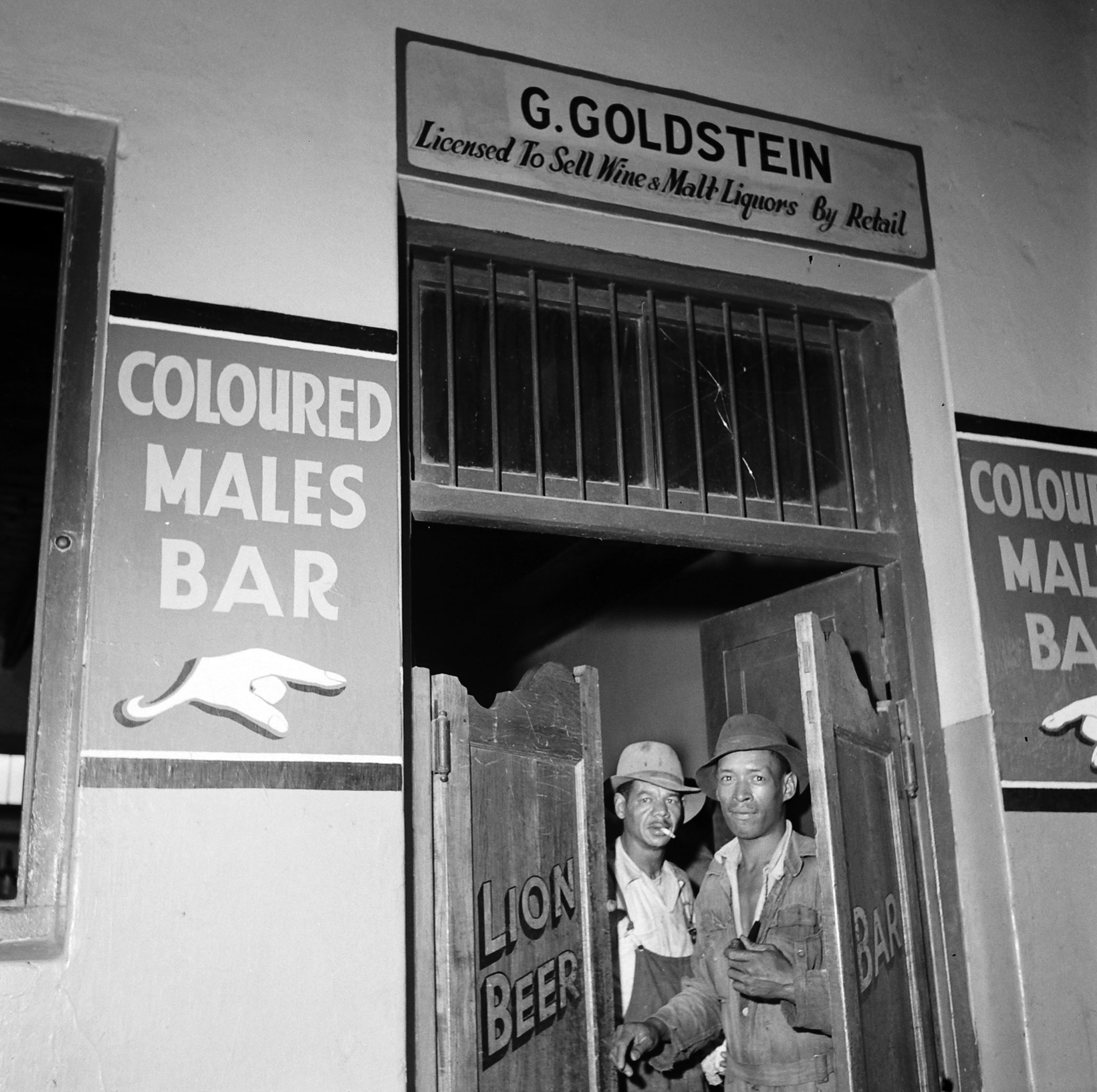

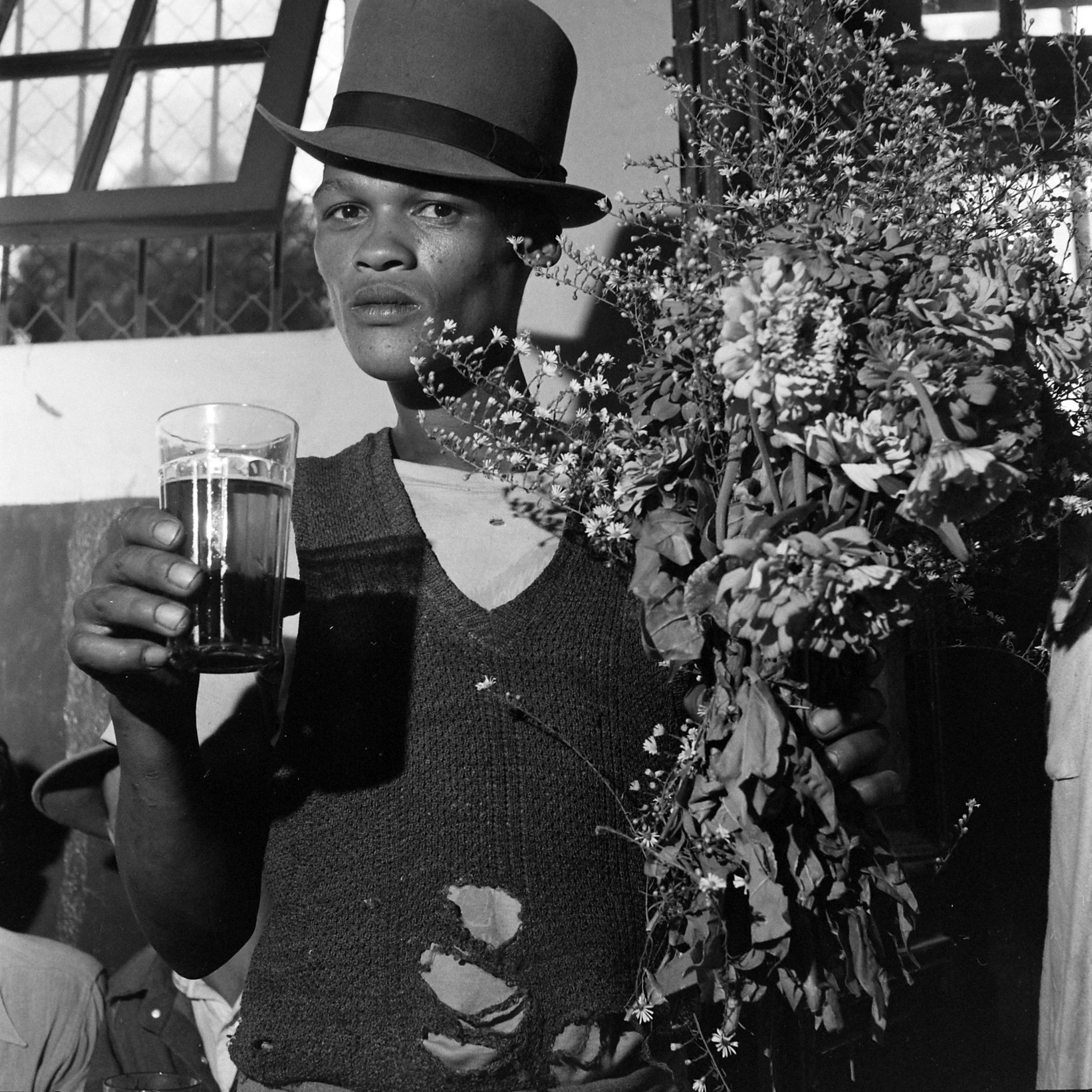

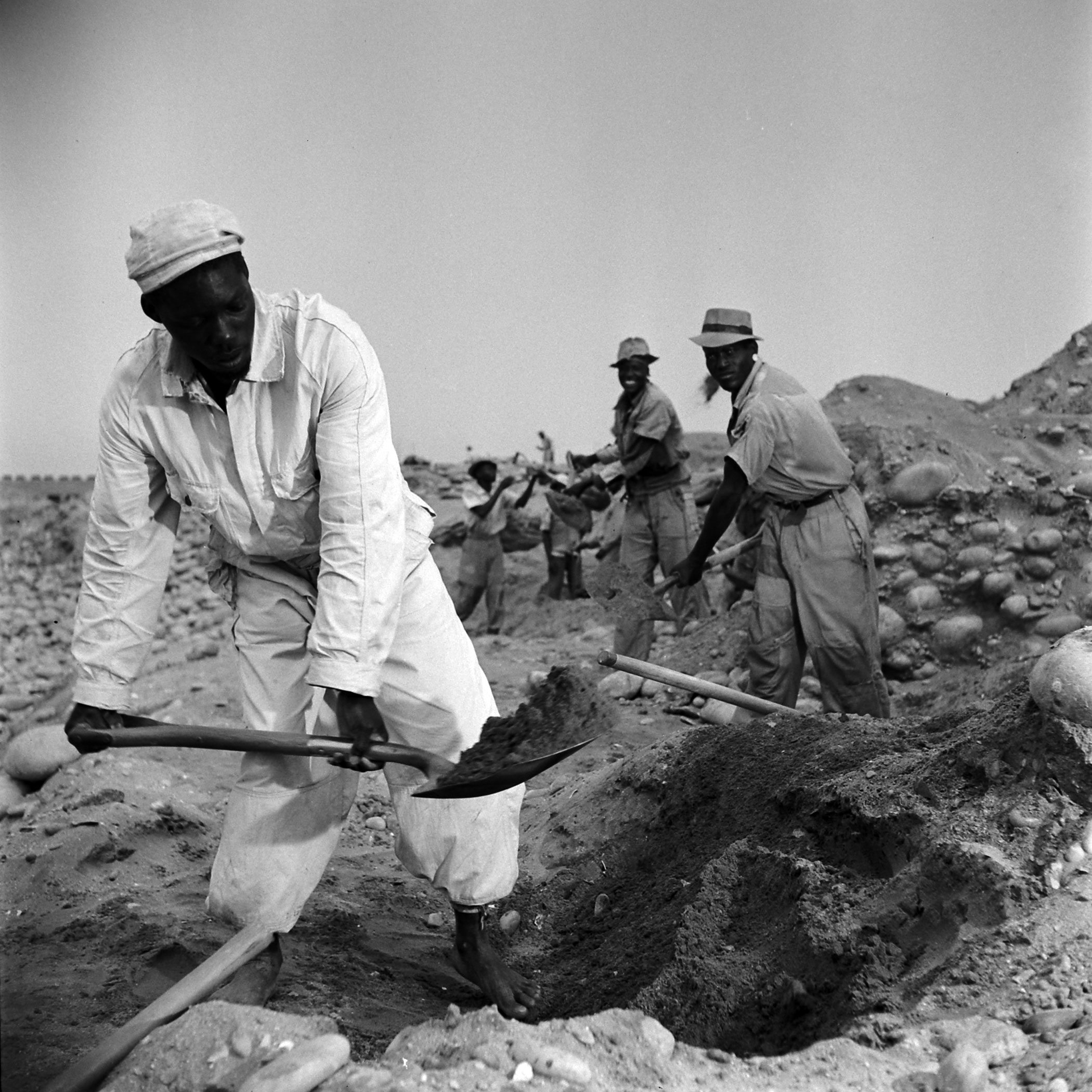

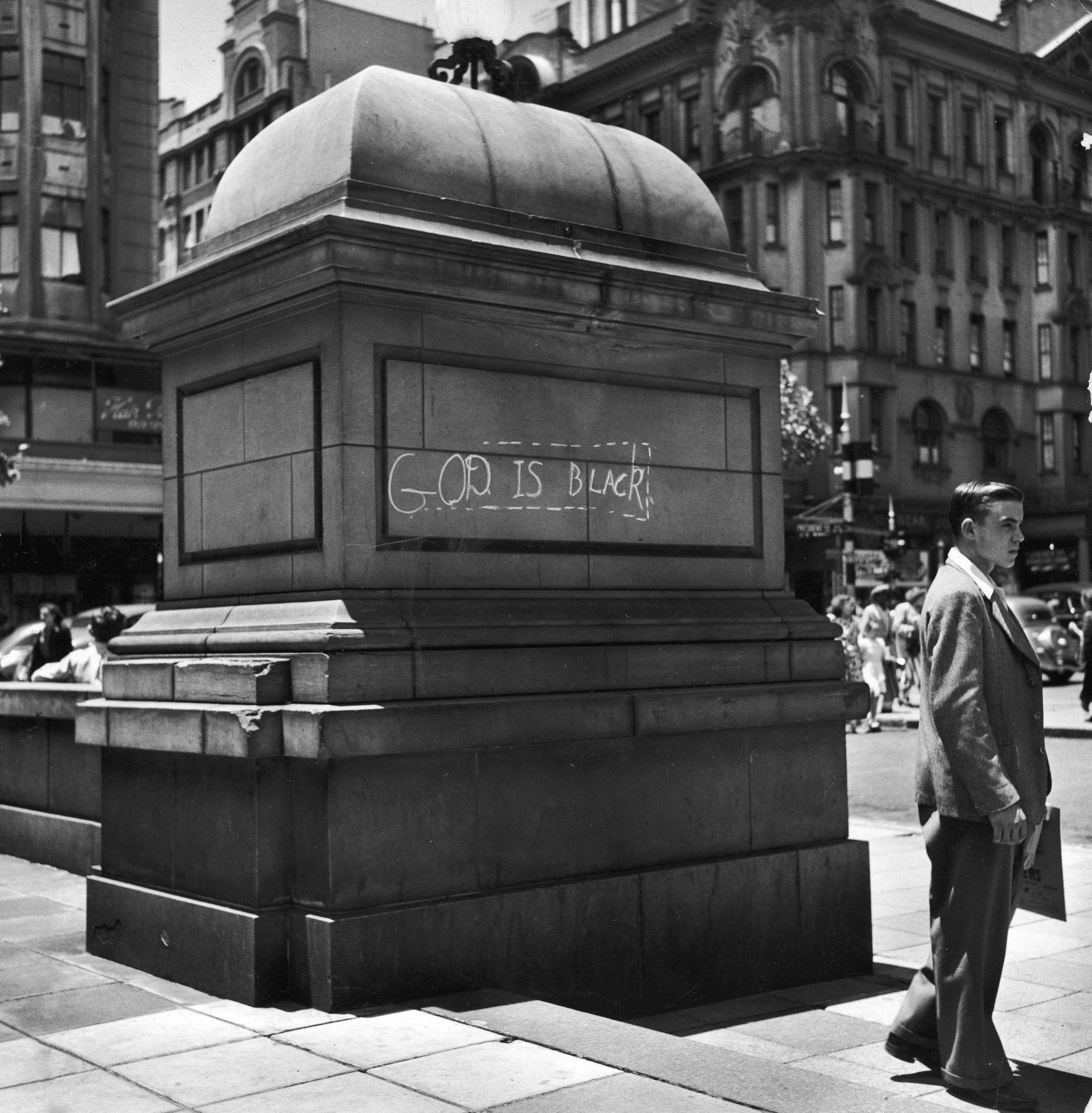

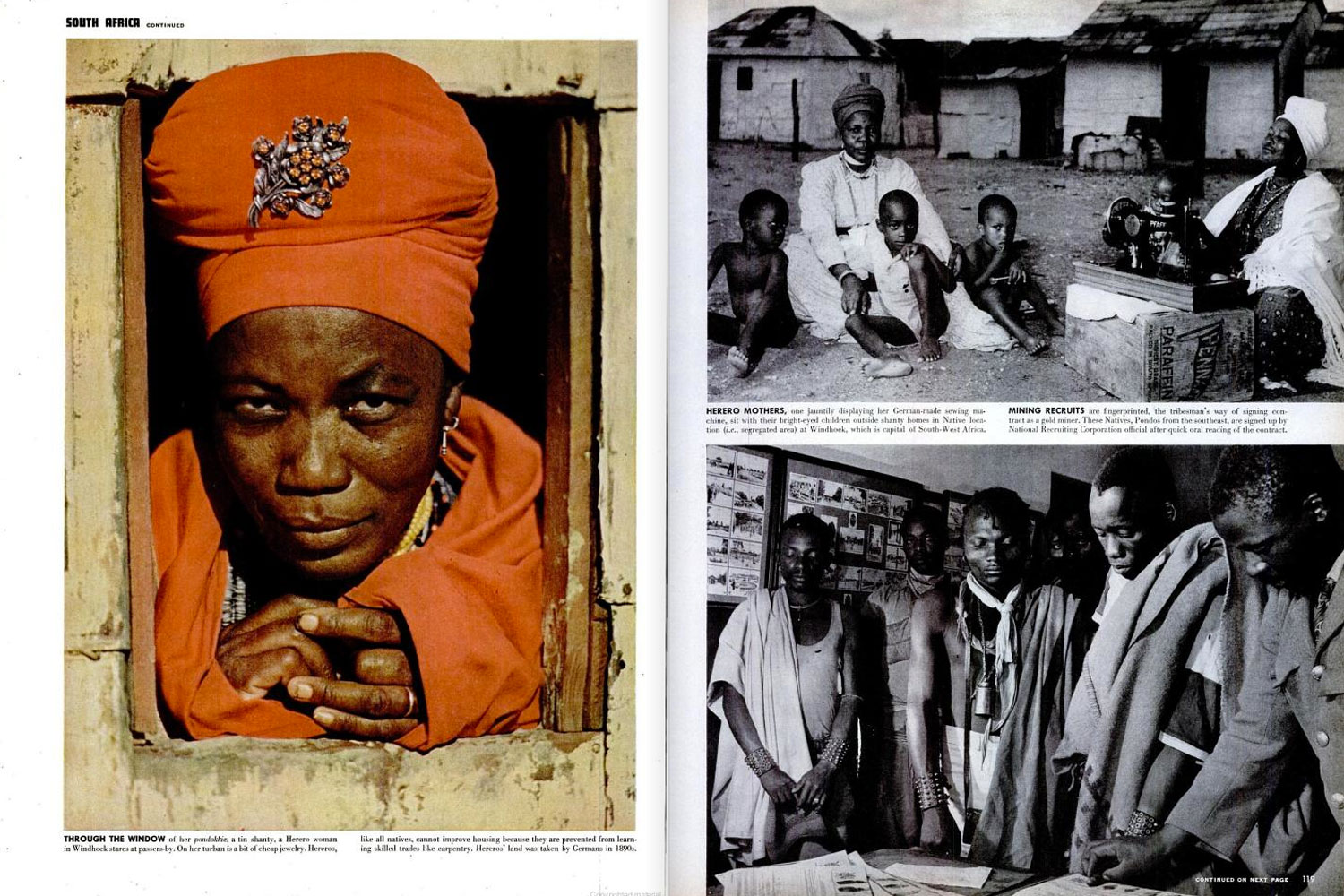

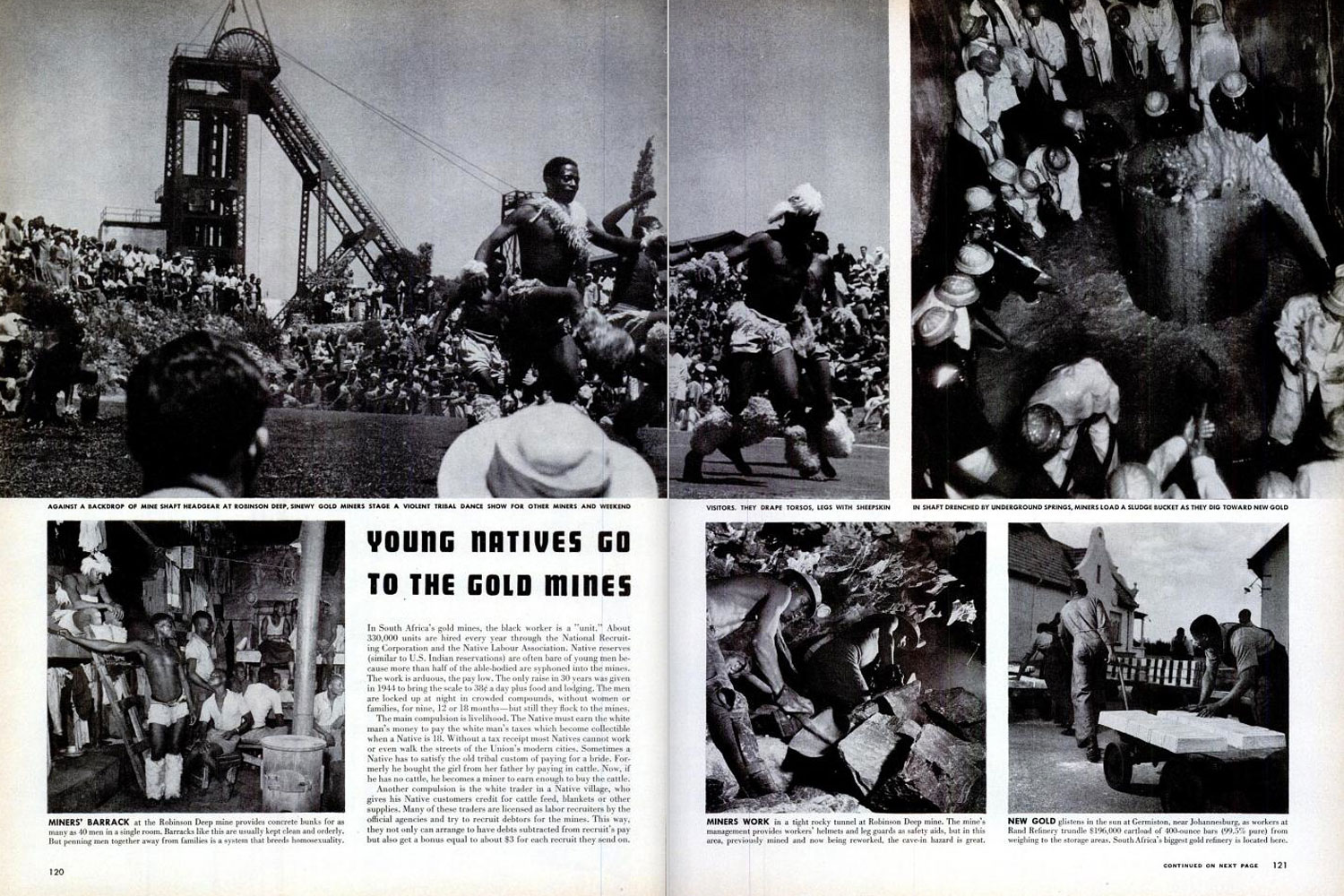

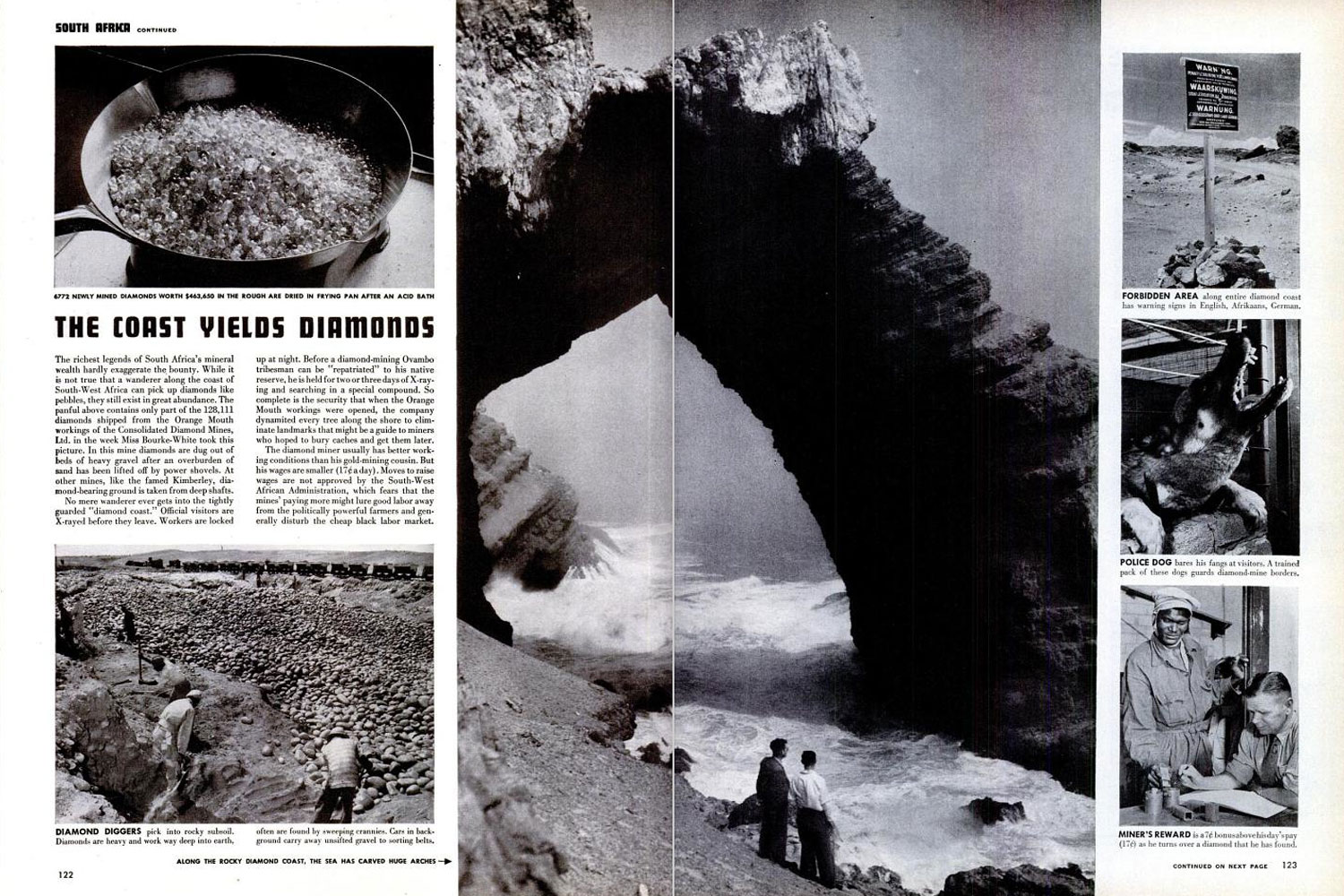

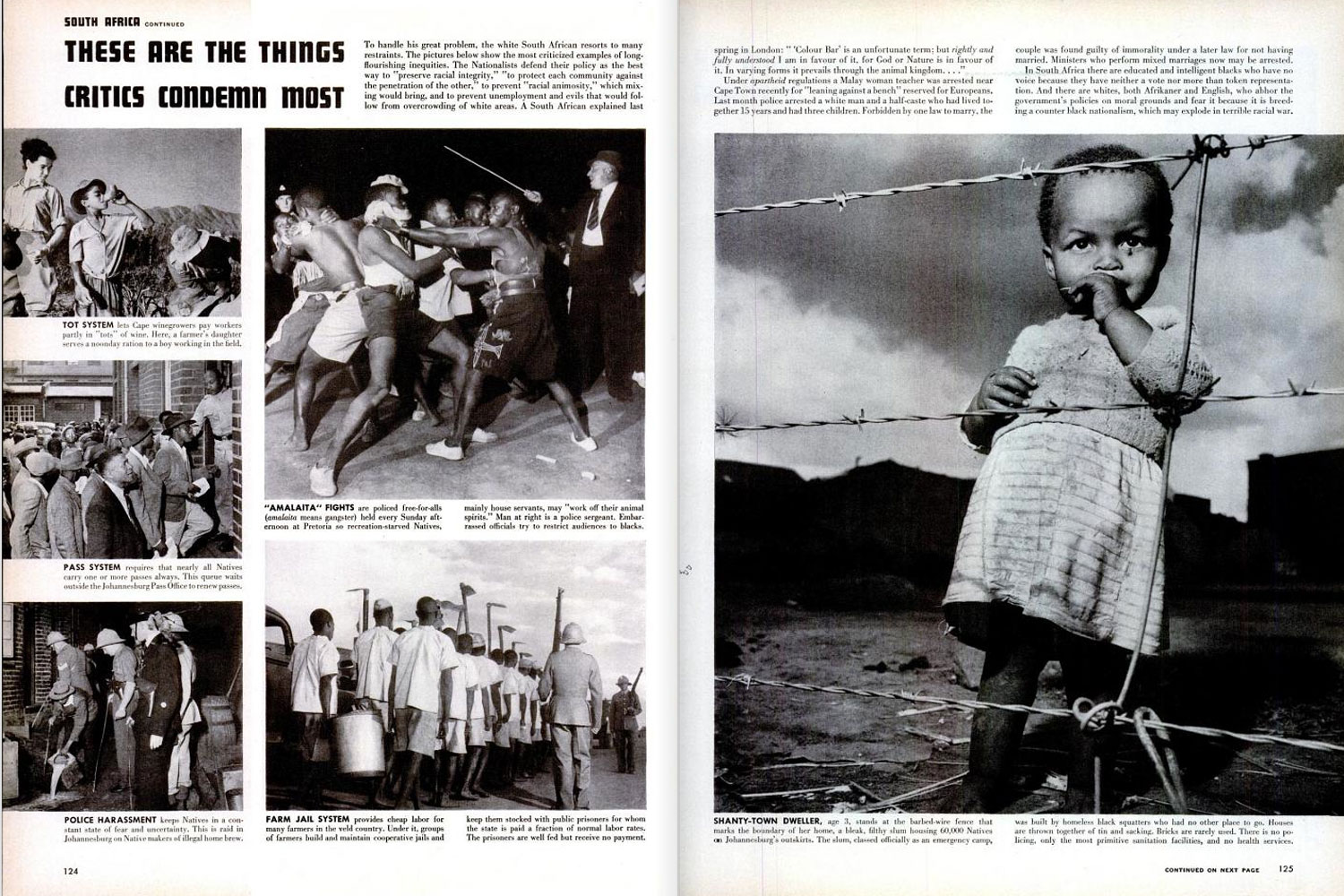

Read next: See the Photos That Gave Americans Their First Glimpse of Apartheid in 1950

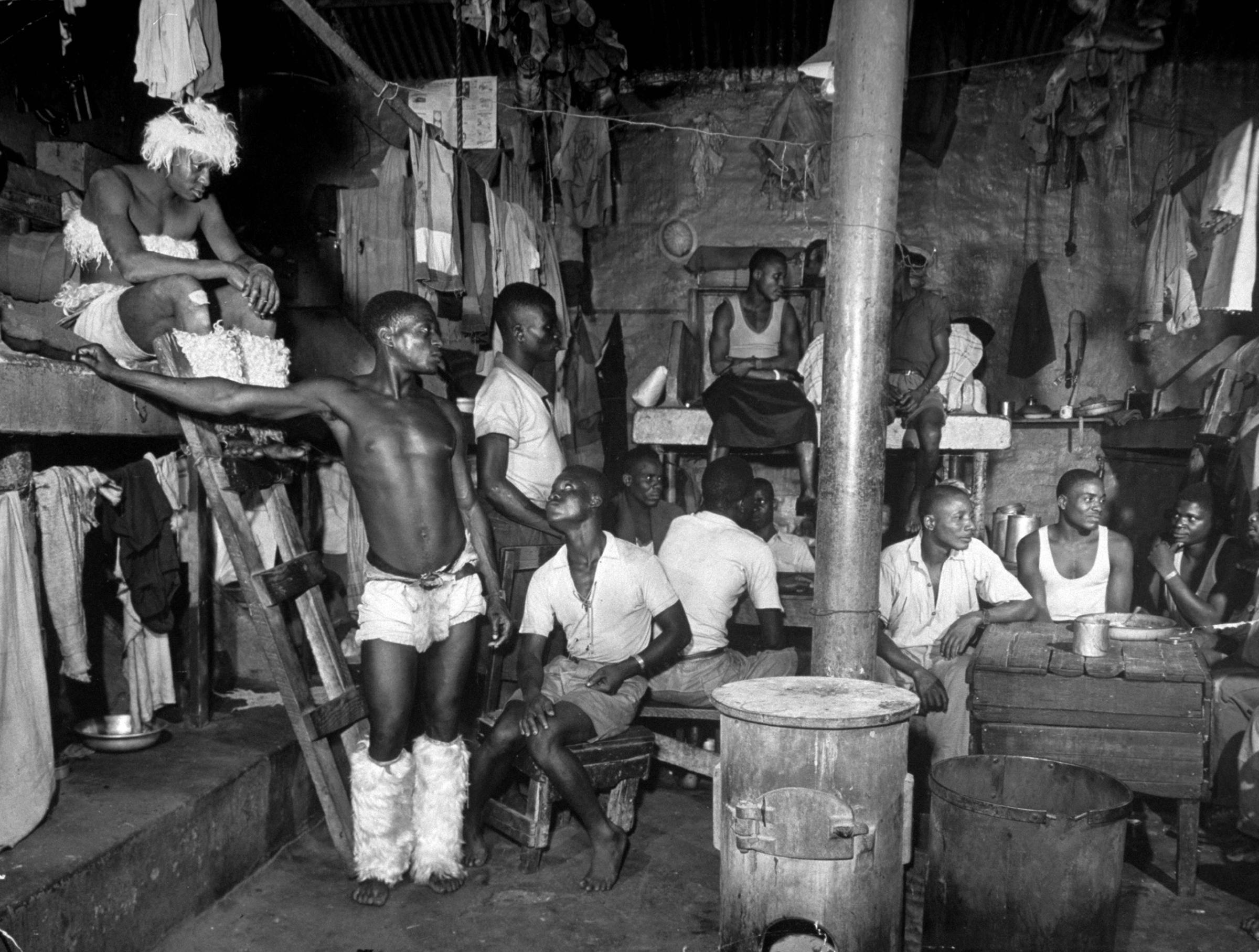

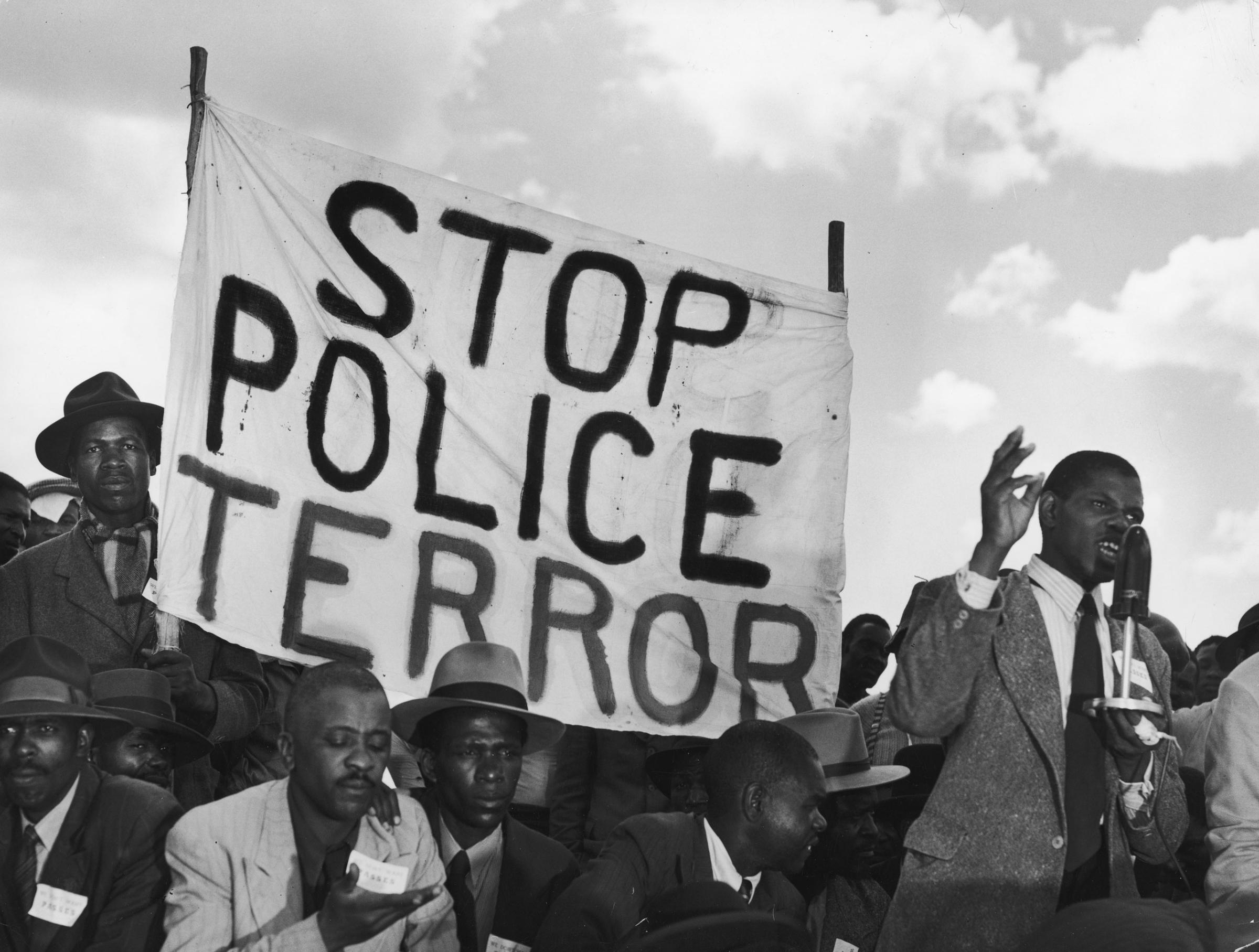

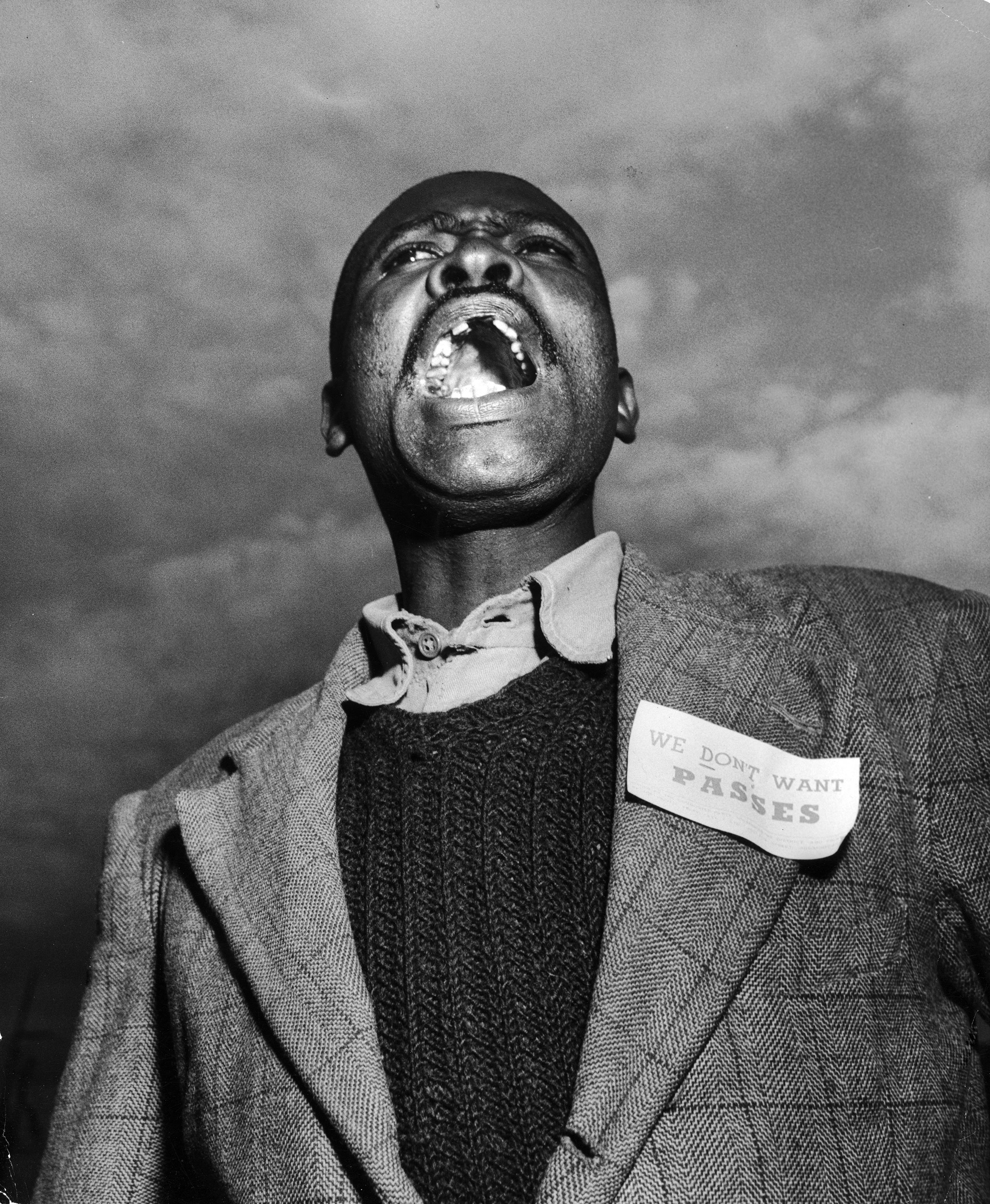

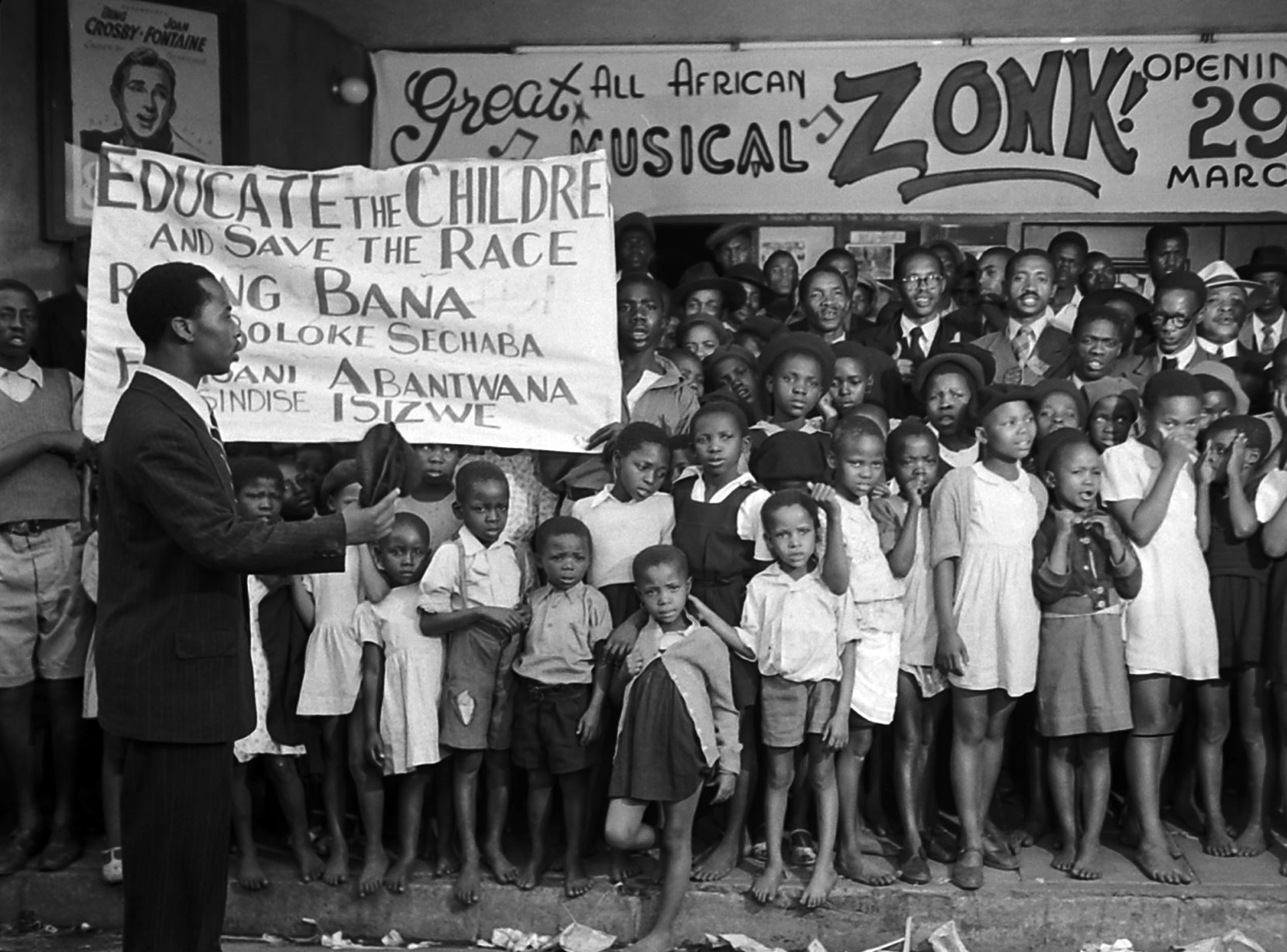

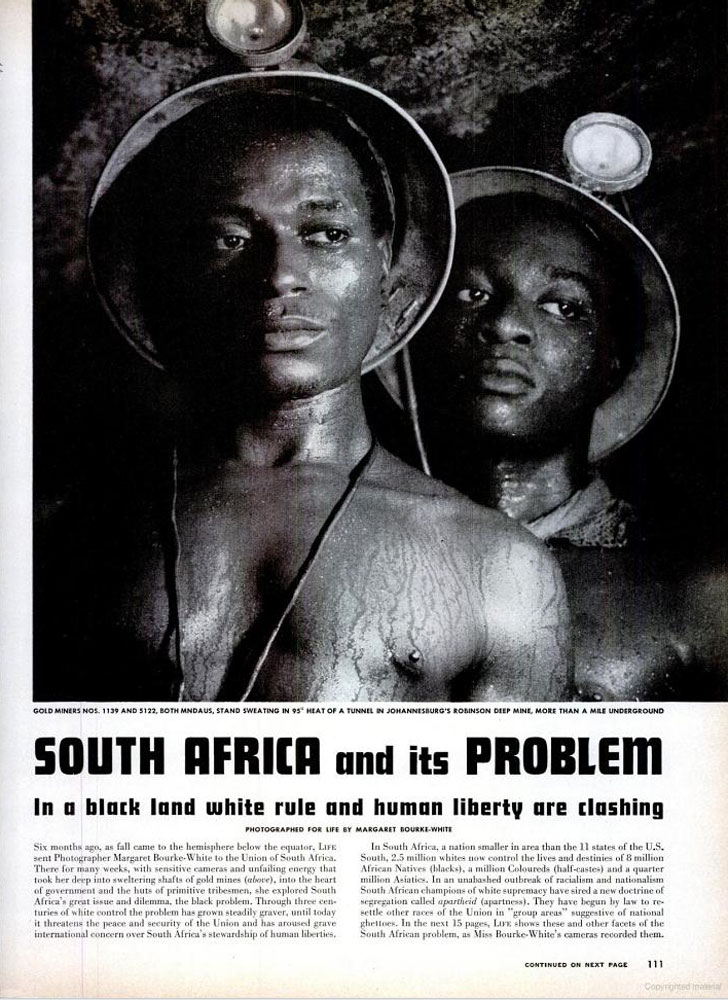

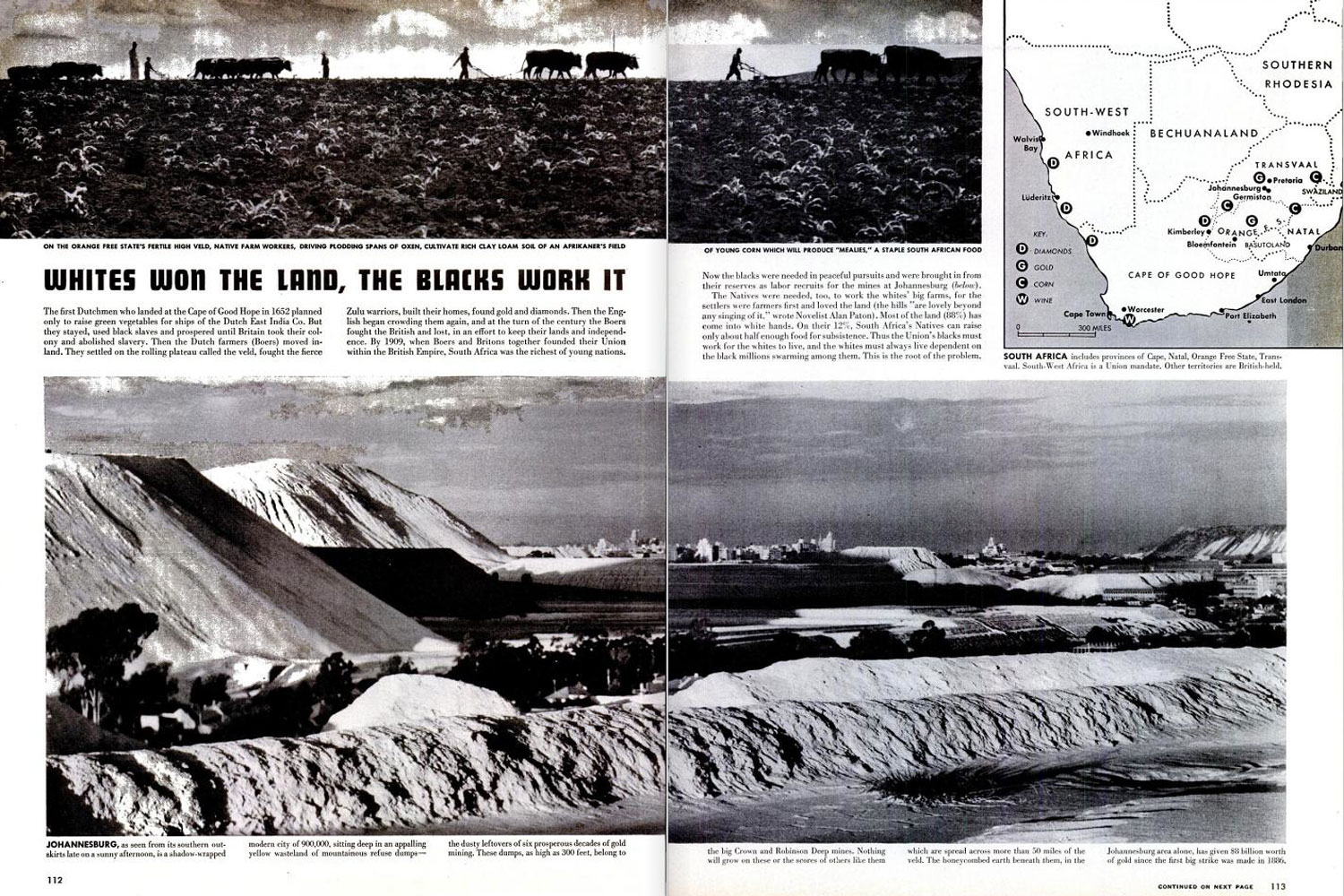

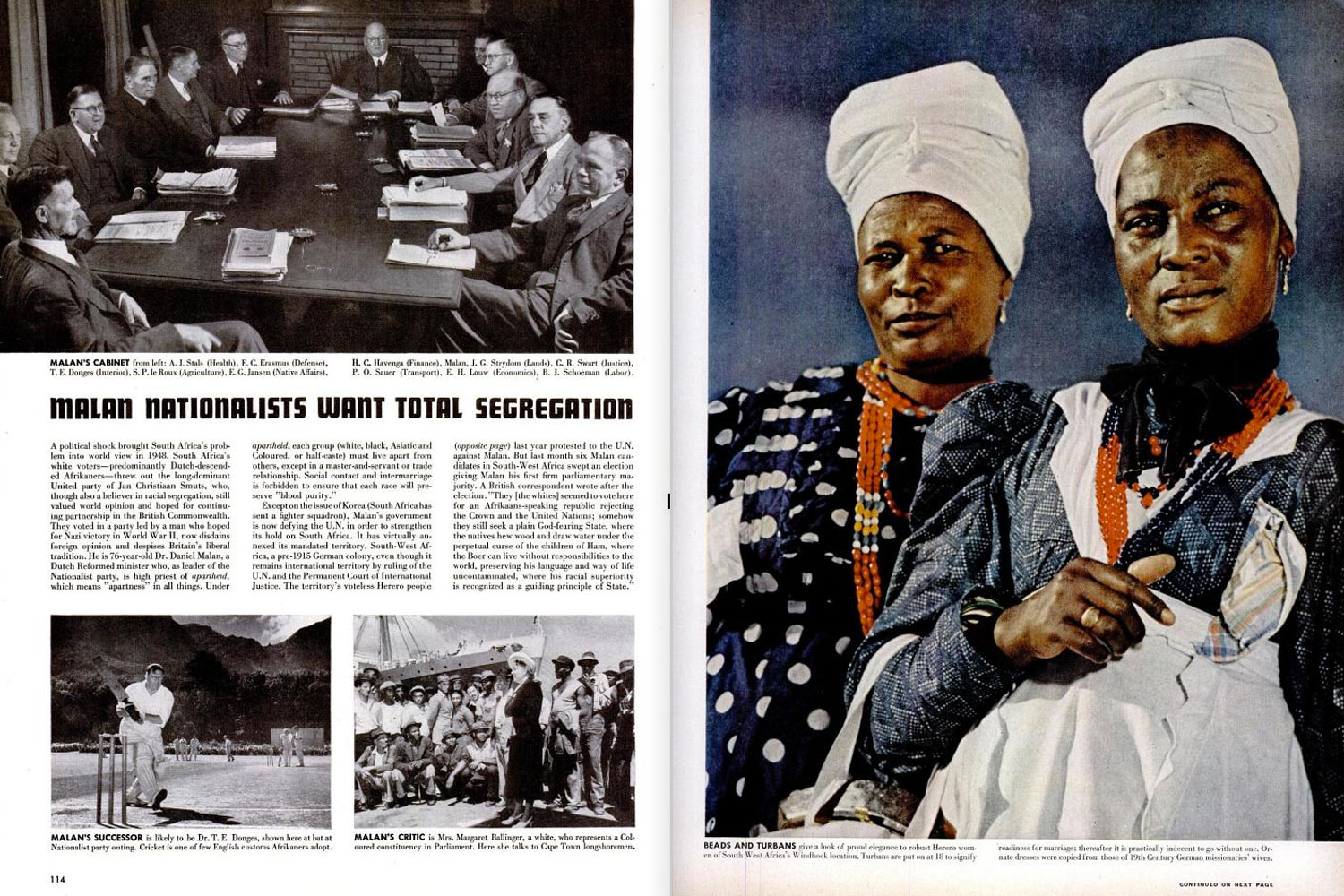

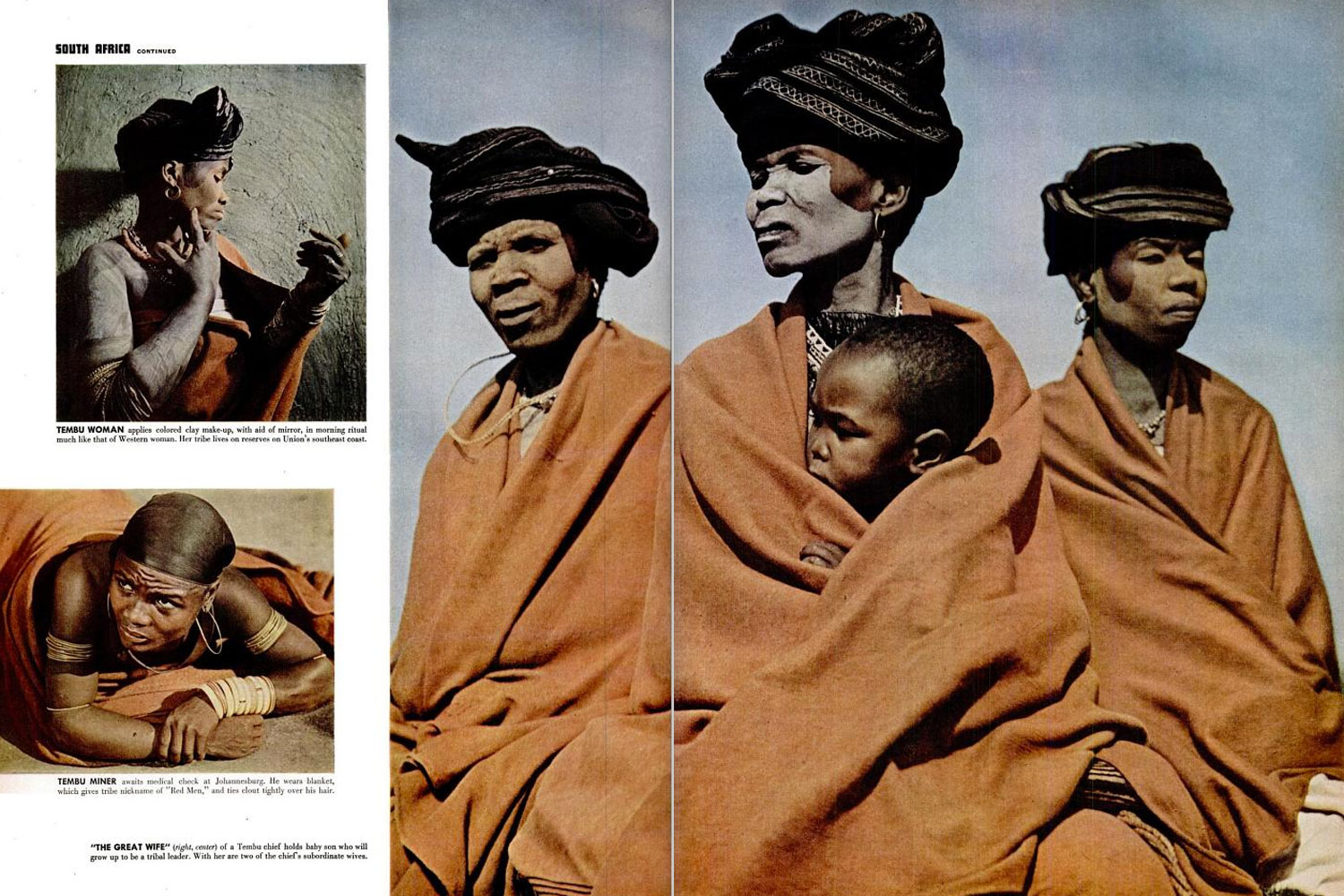

The Photos That Gave Americans Their First Glimpse of Apartheid in 1950

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com