Only politicians with ambition or an agenda choose to trudge through the snows of New Hampshire in the depths of winter. George Pataki has been there five times in recent months, and he isn’t playing coy about the purpose of all these visits. “I have no doubt in my mind,” Pataki said in one of several interviews touting his interest in the presidency, “that I have the ability to run this country.”

Pataki is not likely to get the chance to prove that. Eight years out of office, the former New York governor belongs to a vanishing breed of moderate northeastern Republican. He has supported gun control and abortion rights. He has little national name recognition, less money and zero campaign infrastructure in place.

Pataki publicly flirted with a White House bid in 2008 and 2012, and it’s tempting to interpret his revived interest as a financial gambit. Parlaying the publicity of a campaign into a lucrative gig has become one of the ignominious traditions of presidential politics. But Pataki is serious about running, says spokesman David Catalfamo. And while he has little chance of contending in a crowded Republican field, he does have a connection that could make him a factor.

From 2013 until the end of last year, Pataki was a paid spokesman for a Washington-based advocacy group called the Coalition to Stop Internet Gambling. The organization, formed and funded by the Las Vegas billionaire Sheldon Adelson, is part of Adelson’s hefty wager that a national online-gambling ban would benefit his brick-and-mortar casinos, which include the Venetian and the Palazzo on the Vegas strip.

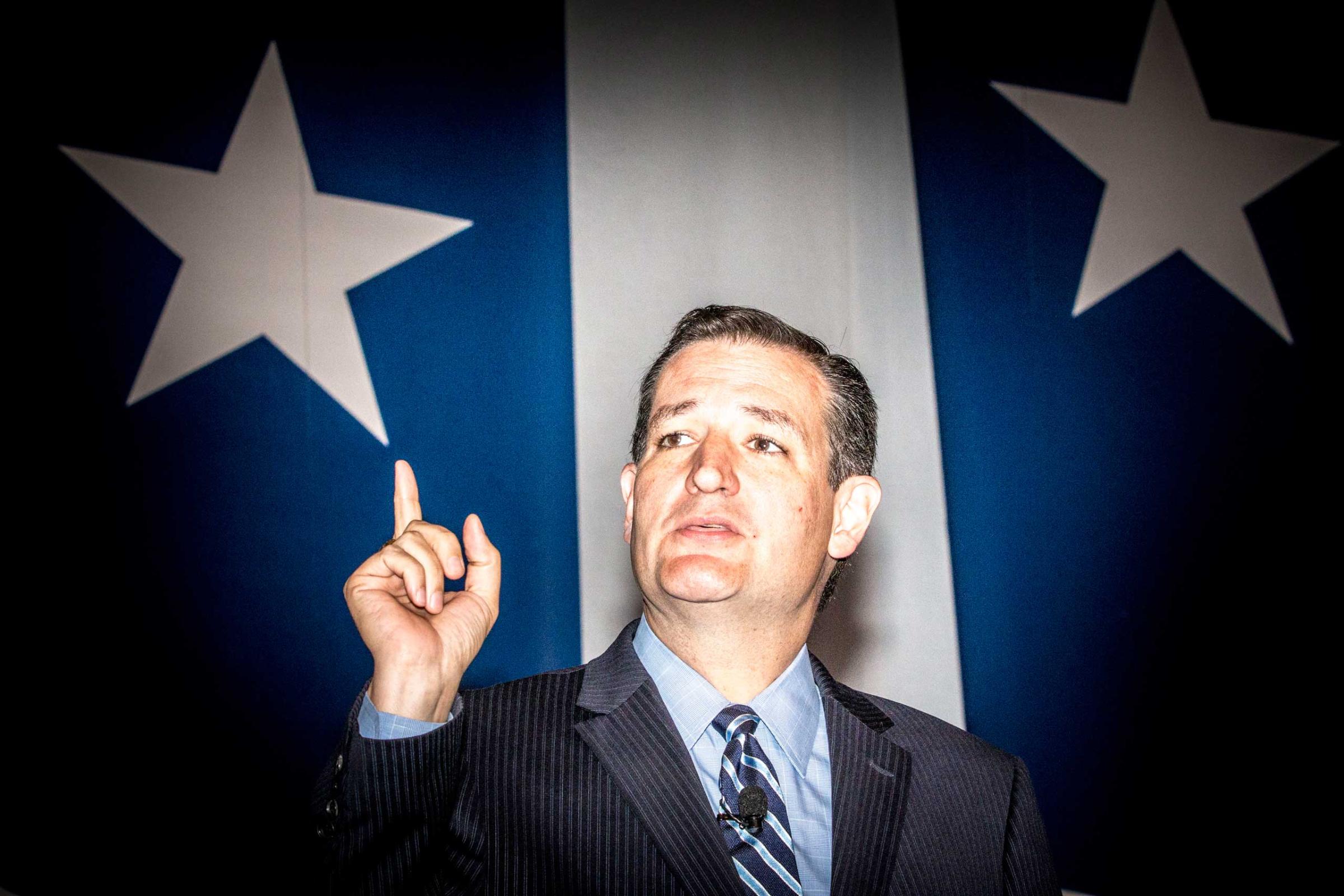

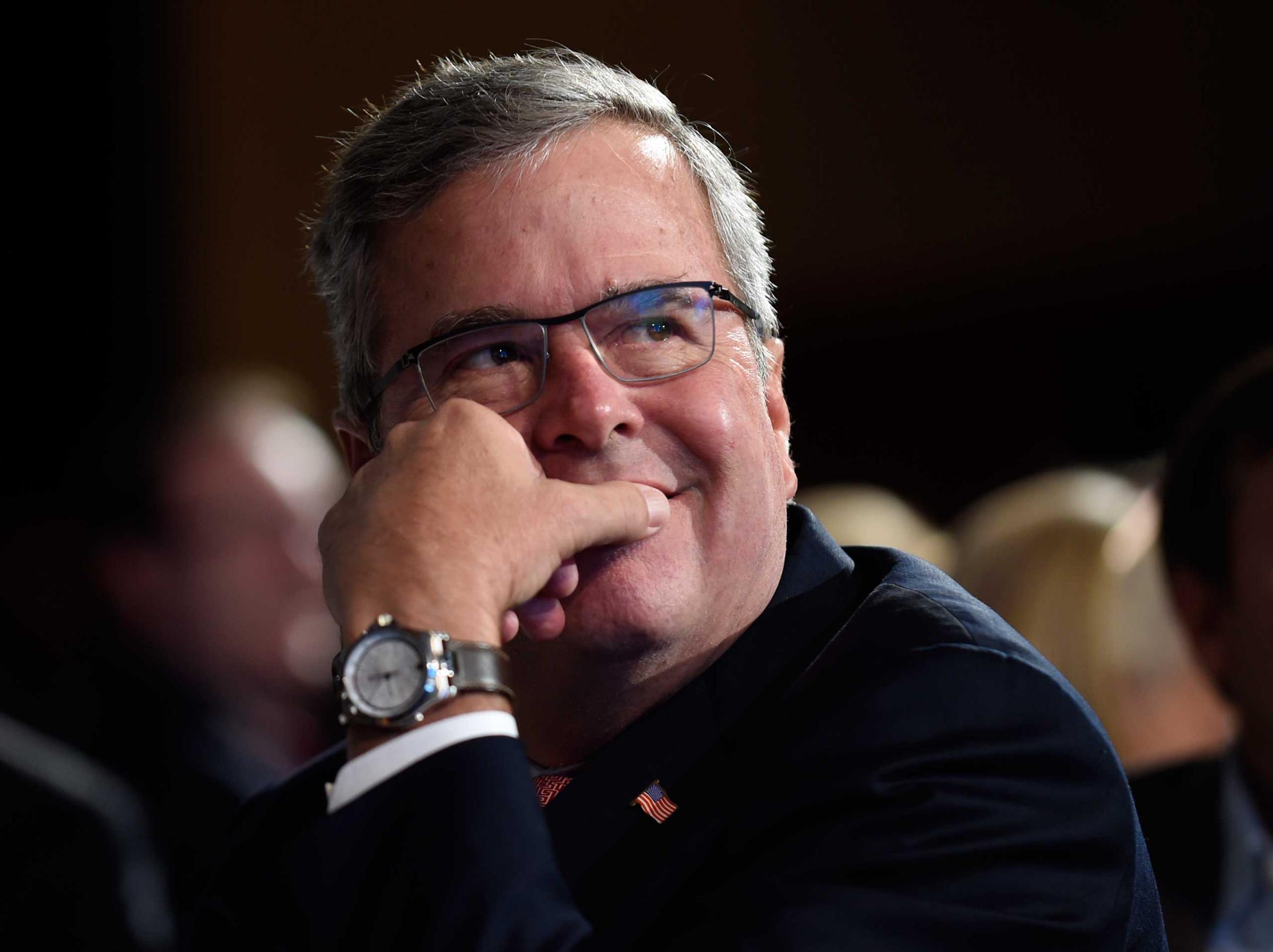

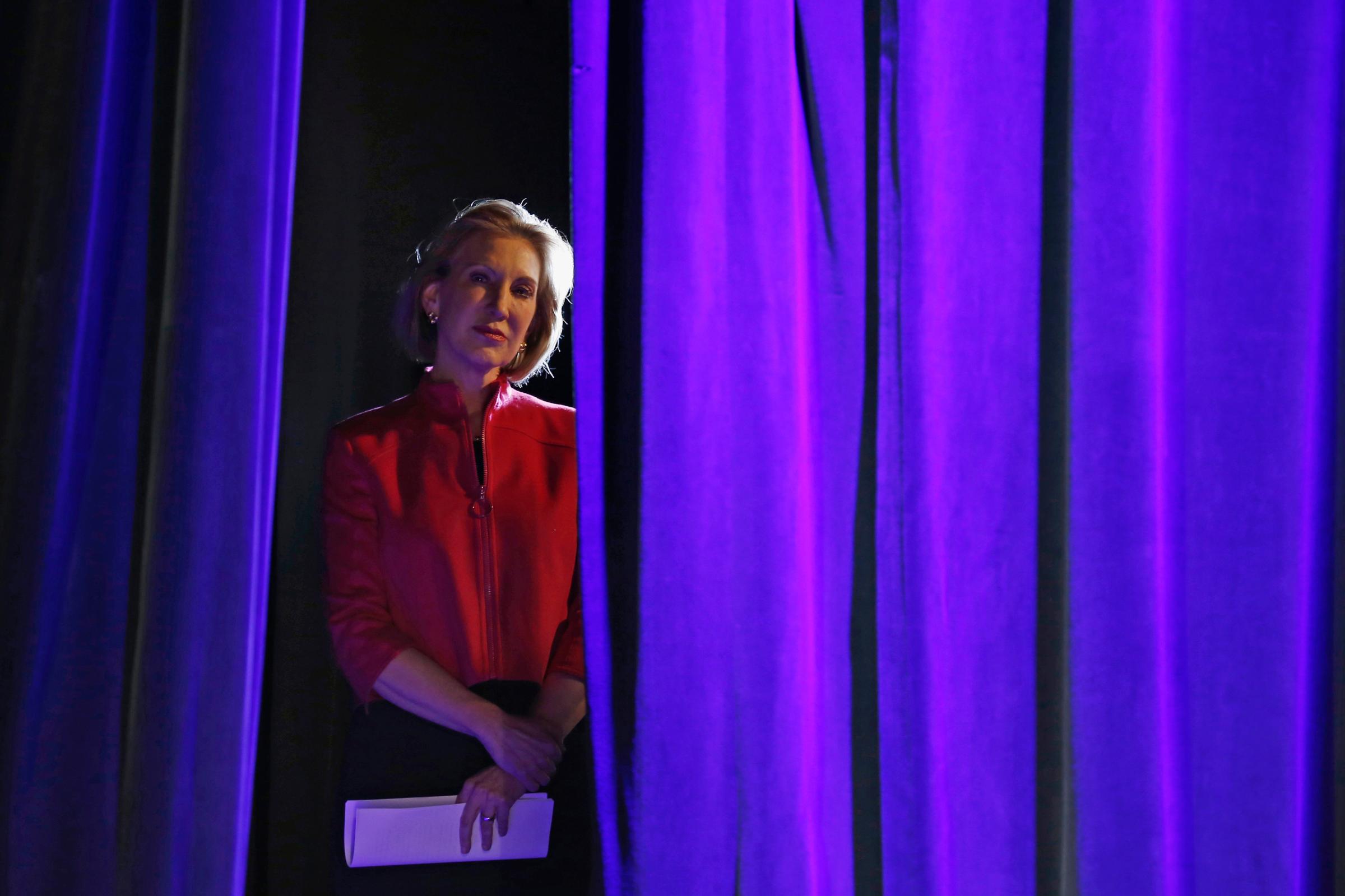

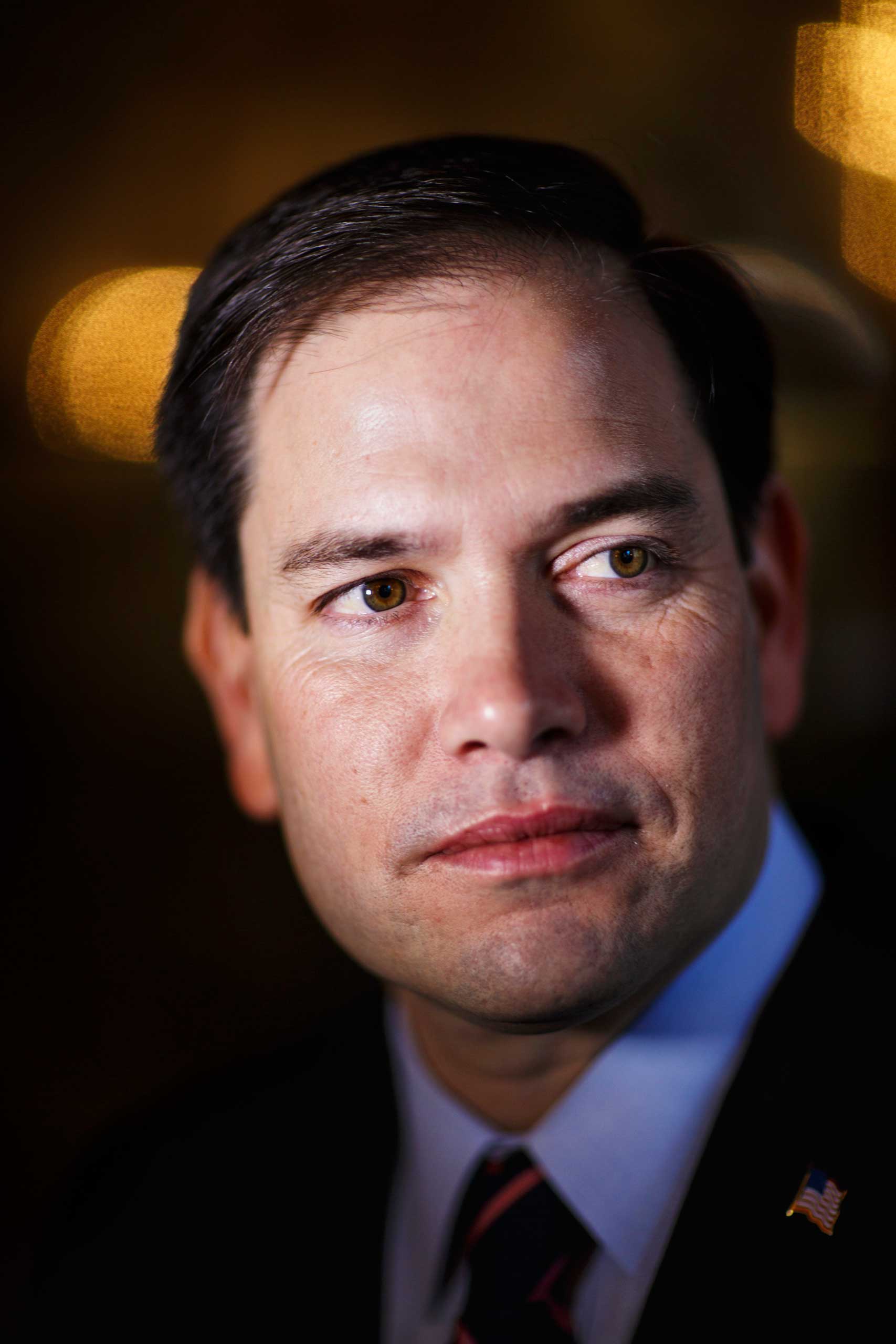

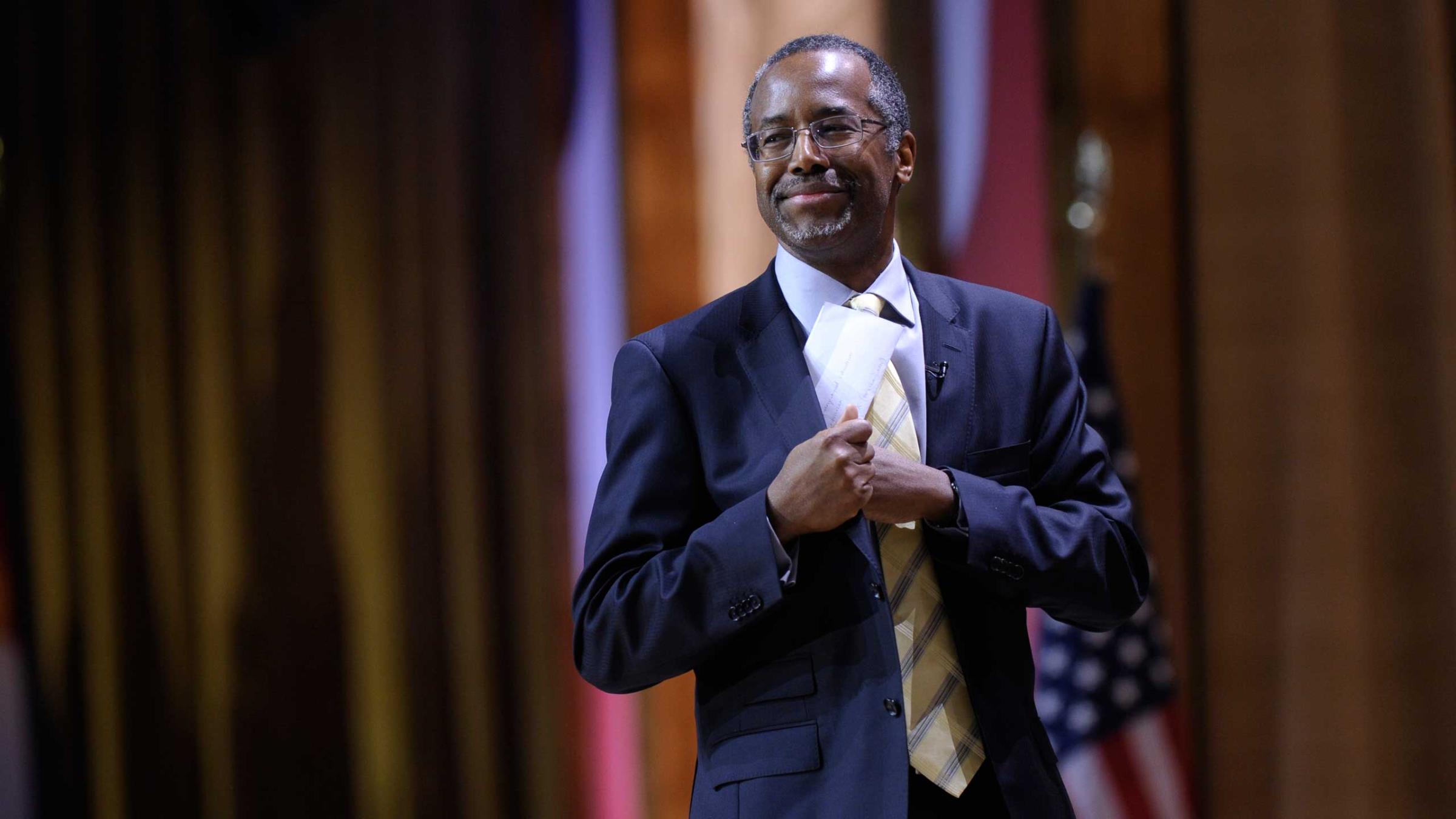

See the 2016 Candidates Looking Very Presidential

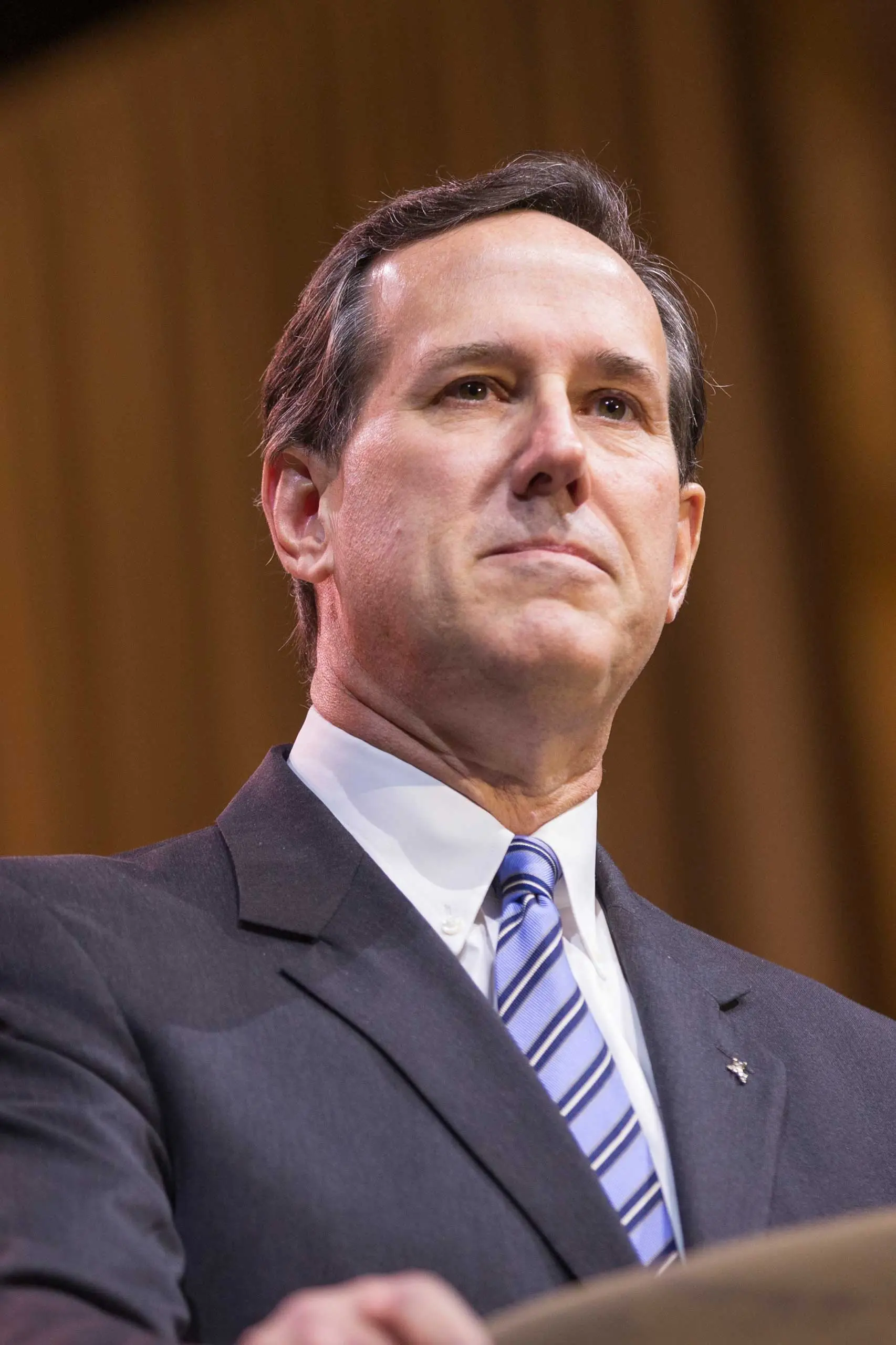

For Pataki, who supported many forms of legalized gambling as governor, an alliance with Adelson could prove lucrative as well. The evolution of campaign-finance laws have created a system in which a single benefactor is capable of sustaining a lean presidential campaign for long enough to grab the national spotlight. Wyoming businessman Foster Friess kept Rick Santorum afloat for long stretches in 2012, while Adelson—the single biggest donor of that campaign—forked over enough money to let Newt Gingrich spend months traveling the country to torture Mitt Romney.

Adelson has no plans to match the $150 million or more he shelled out four years ago, according to a source close to him. But is still expected to spend in support of his signature issues. A hawkish foreign policy devoted to the security of Israel remains his chief concern. But he has also lavished cash on Republican candidates and committees amid his push for a national Internet-gambling ban.

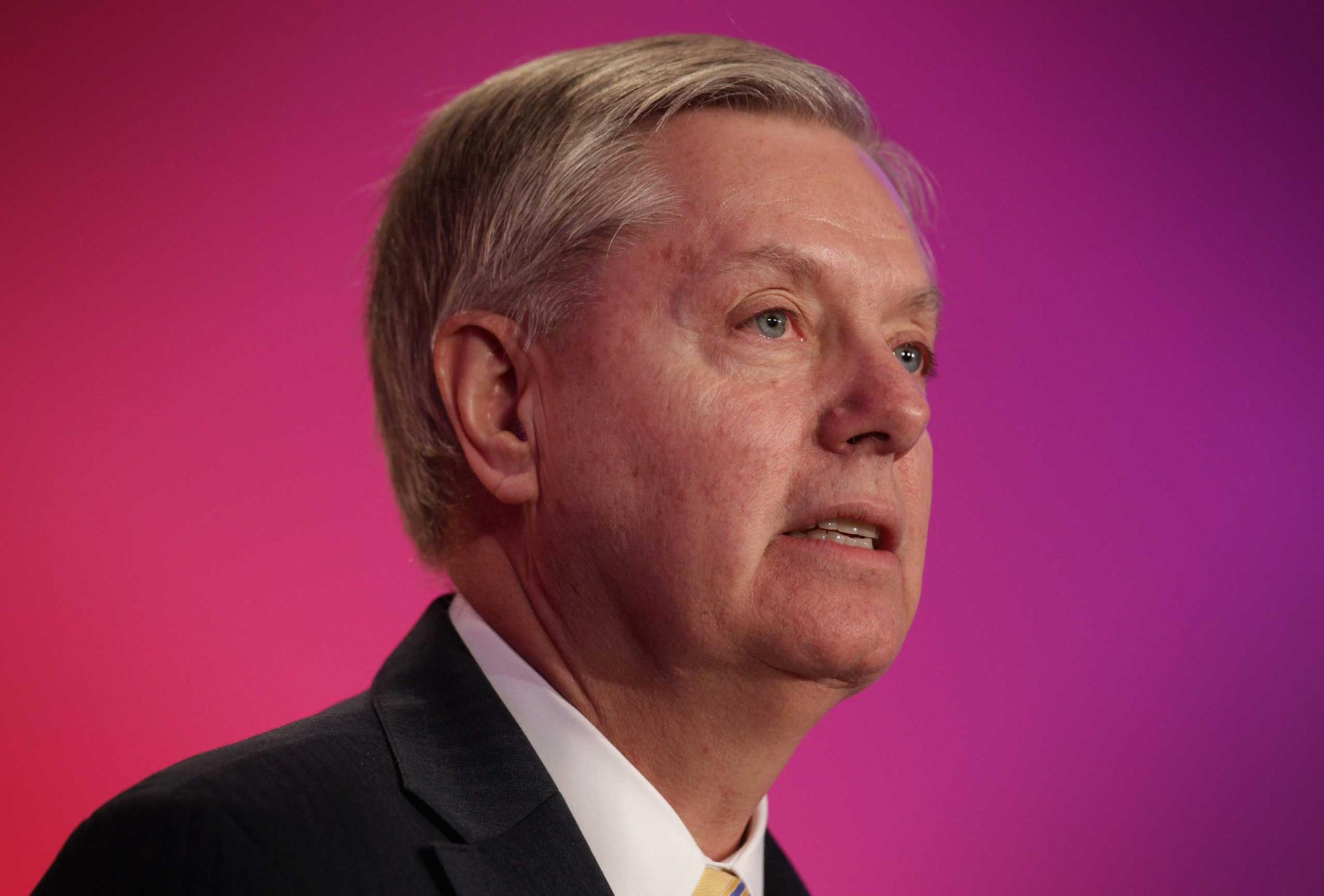

Pataki isn’t the only surprise candidate in the Adelson primary. Take Lindsey Graham, the Republican senator from South Carolina who is also publicly weighing a long-shot campaign for the GOP nomination. In March, Graham introduced a bill in the Senate that would effectively impose a national Internet-gambling ban. Graham will reintroduce the same measure this Congress, says communications director Kevin Bishop.

Graham calls online gambling a threat to public safety. “I think people in the criminal world and terrorist world could get a benefit from it,” he told TIME. But pushing the ban has also paid off for the South Carolina Senator, who reaped at least $31,200 in 2013 from Adelson, his wife and two daughters, according to public data compiled by the Sunlight Foundation.

The Adelson derby isn’t just for the also-rans. Last spring, a slew of top-tier GOP presidential hopefuls, including Jeb Bush, Chris Christie and Scott Walker, made pilgrimages to Las Vegas to speak at the Republican Jewish Coalition’s annual conference. It isn’t likely that Adelson will shower cash on a single favorite in 2016, as he did with Gingrich four years ago, but he’s willing to crack open his wallet to keep his issues at the forefront of the debate—and to make life difficult for candidates who don’t see eye to eye with him.

If support for Israel is Republican orthodoxy, gambling is more complicated. It is a rare issue that splits the GOP, pitting religious conservatives against states’-rights activists and libertarians. The prominent anti-tax conservative Grover Norquist told TIME in an interview that Congress should reject a national ban and let states decide the issue. “You don’t want the federal government coming in,” he says.

Adelson says he opposes online gaming on moral grounds. “ You would think the chairman of the world’s largest gaming company would pursue any aspect of gaming which could increase profits, right?” he wrote in an op-ed for Forbes in 2013. “Ordinarily that is true—but online gambling is ‘fool’s gold.’ Whether it is full casino gaming, poker only, or anything in between—this is a societal train wreck waiting to happen.”

That’s all a bit rich: from at least 2001 to 2007, Adelson’s company pursued the possibility of developing its own gaming website before abandoning the idea. And while it’s unclear whether Graham’s bill can pass Congress, Adelson is still changing the debate through donations to old allies and potential new ones. In 2014, he shelled out the individual limit of $2,600 to nearly every successful Senate Republican challenger, including Thom Tillis, Cory Gardner, Tom Cotton, Dan Sullivan, David Perdue and Bill Cassidy, according to CQ Moneyline.

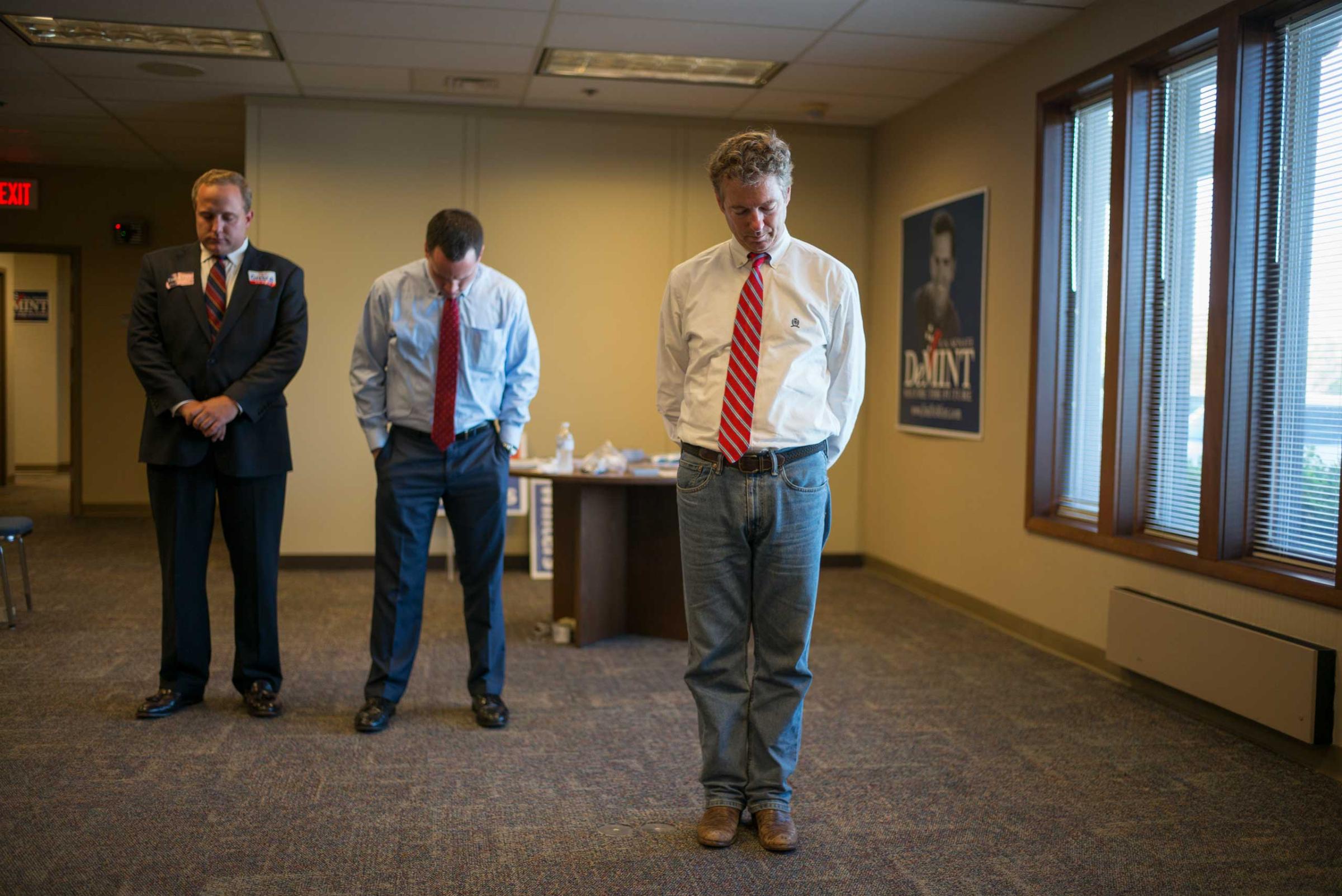

Photos: On the Road with Rand Paul

And sometimes he wields his influence in unseen ways. Late last year, Republican Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi circulated a letter to colleagues protesting Graham’s online gambling bill. Wicker, the new chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, argued a national ban would give the federal government regulatory powers that are reserved for the states. “We believe that a bill that encroaches on the long-standing authority of states to decide issues related to gaming is not the answer,” says the Dec. 3 letter, a copy of which was obtained by TIME.

The push was dropped, an aide to Wicker says, when it became clear the bill wouldn’t pass. But it also had the potential to strain relations with Adelson, who gave $13.2 million—more than any other GOP-aligned donor according to Politico—to help the party snag the Senate majority in 2014.

Pataki thinks he may have the background to whet Adelson’s appetite. The former three-term governor was running Albany during the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and is “ardently opposed to the President’s leading from behind strategy on foreign policy,” says spokesman Catalfamo. And Adelson isn’t the only potential benefactor with whom he rubs elbows. “He’s very friendly and has long relationship with a lot of folks who are billionaires,” says Catalfamo, including the billionaire Koch brothers and various Wall Street titans.

“People don’t remember who I am,” Pataki presidential told the conservative website Newsmax this month, “but we can remind them.” He certainly has a friend with the money to help.

With reporting by Zeke J. Miller

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com