The first review of a Nirvana recording was bad. I recall it saying that we were like Lynyrd Skynyrd but without the flares. That was a comparison that was bound to upset us. Lynyrd Skynyrd had some good songs (check out the heavy riff on “Saturday Night Special”), but there were other connotations beyond the music. Lynyrd Skynyrd was culturally different than us. The line in the sand was drawn as we opposed the 1970s redneck ethic. The rebel flag of the Confederacy, central in southern-fried rock imagery, was also an icon of “hair metal” of the 1980s. So even if a band like Lynyrd Skynyrd rocked, it had to be held at arm’s length, so as not to contaminate our own ethics and sensibilities. Nirvana’s anti-establishmentarianism was rooted in the punk rock of the seventies and eighties. We had our own symbol of rebellion, the circled “A” for anarchy: The cheerleaders wearing it in the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video are not sporting fashion; the display was a conscious statement of values – albeit tied to established power mediums.

Establishment rock needed storming in 1992, and our album Nevermind led the charge. Virtually overnight there was a new musical regime as the bands that drew from the well of seventies hard rock became displaced by bands tied to punk. Yet while there was musical change, many things stayed the same regarding the music business. What if we’d adopted principled independent positions, like the bands Pavement or Fugazi, who refused to sign with major labels? Would we ever have been plugged into the major distribution networks dominating at the time? I don’t think so. Nirvana’s revolution was in heavy rotation on MTV – a subsidiary of some corporation. Our own label, DGC, was a business division emanating from Matsushita, a colossal Japanese industrial firm. Yet look at band interviews during the Nirvana boom, where we dutifully promote our fellow subterranean bands. We knew we were in the belly of the beast and wanted to effect social change through the power of music. And I feel we got the message through. There seems to have been an impact other than other bands picking up the musical dynamics we knew so well. After Nevermind hit number one, rock music could be about having a social conscience – just like it was a generation earlier. That was a tangible effect. However, it is one thing to have a consciousness of issues and it is another matter to organize them into a movement. We were a rock band, not political organizers. We had roadies, so we didn’t even need to carry and set up our own gear anymore. We played the music but we didn’t organize the show.

After the music and crowds leave, who’s going to be there to clean up the glass and splintered furniture and start holding meetings?

More people in the U.S. now engage with politics through social media on the Internet than attend public hearings about local and state politics. Comments online are instant reviews by readers that can reach into the thousands on a single story. Who the heck reads this far into user comments? Public hearings, on the other hand, might have one or two people watching actual lawmakers do the people’s work. Engaging government is where practical social reform can occur – which is why we have so little practical reform! Instead we have notions of subversion like the recent Occupy movement. It held promise as a group brimming with a passion for reform getting out and actually trying to do something. Regrettably it turned into a bunch of people running blind down dark alleys. I recognized this early on, so I never endorsed Occupy. It must have been a relief for many of those taking to the streets to get things off their chest – and a lot more fun than sitting in on a boring public hearing.

The people who attend hearings are mainstream types who probably listen to Céline Dion – hardly the kind of subversive music that primes storming the barricades. In the year 2000 I watched images of the fall of Slobodan Milosević on cable news channels. The Serbian parliament was stormed by protesters and I fell out of my chair when I heard a song blaring among black smoke billowing from the windows – it was “Smells Like Teen Spirit”! I thought, “Now this is a great music video!”

Organizing requires submission to a group, not subversion. Remember that another term for “band” is “group”: The band works together to make its sound. With political association, instead of drums and guitars, the group elects officers and passes action resolutions, all while following the rules of Robert’s Rules of Order. In Let’s Talk About Love, Carl Wilson makes the point that you can’t think you’re a hipster in politics, because it is about human lives. The truth is that someone with a self-image as a subversive needs to work with a mainstreamer Céline Dion fan to meet reform goals. That doesn’t mean you have to listen to Dion’s songs or that they need to embrace your own subculture. But you do have to listen and work with others – just like a good band does.

Look at it this way: Imagine that an alternative cultural movement succeeds in storming a capitol building – after the music and crowds leave, who’s going to be there to clean up the glass and splintered furniture and start holding meetings regarding the people’s business? The answer will always be found among the kinds of folks willing to spend long hours in meetings, and most of those people are more like Céline Dion fans. That’s not saying that rock fans who’d prefer to attack buildings can’t be involved; this is part of the journey to the end of taste. But who is the gatekeeper to the new legislature? If the message is that Céline Dion fans need not apply, that reeks of oppression. Just like The Who sang: “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss”.

Don’t call me a sellout because I seem to conform to established political norms. I am the chair of the only group in the United States promoting proportional representation. I am a currently unaffiliated voter who has stood up for political association, which is suffering under a state monopoly over party nominations. I am an active member of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, a non-partisan group with deep roots in the nineteenth century. I play a lot of accordion. This all is decidedly unhip, I guess. I could claim that these political endeavors are all totally subversive; but admitting that could blow my cover, so I won’t. Wilson nails it with, “what liberal critics label subversive seldom pertains to practical social reform.” I engage in practical social reform.

Subversion is a cool look, but without action it is nothing more than a pose. Of course some hipster can kick around Céline Dion, but this kind of thing is too easy in the course of the care and feeding of a smug self-image. I do my own thing, because as Dion sings, “My Heart Will Go On.”

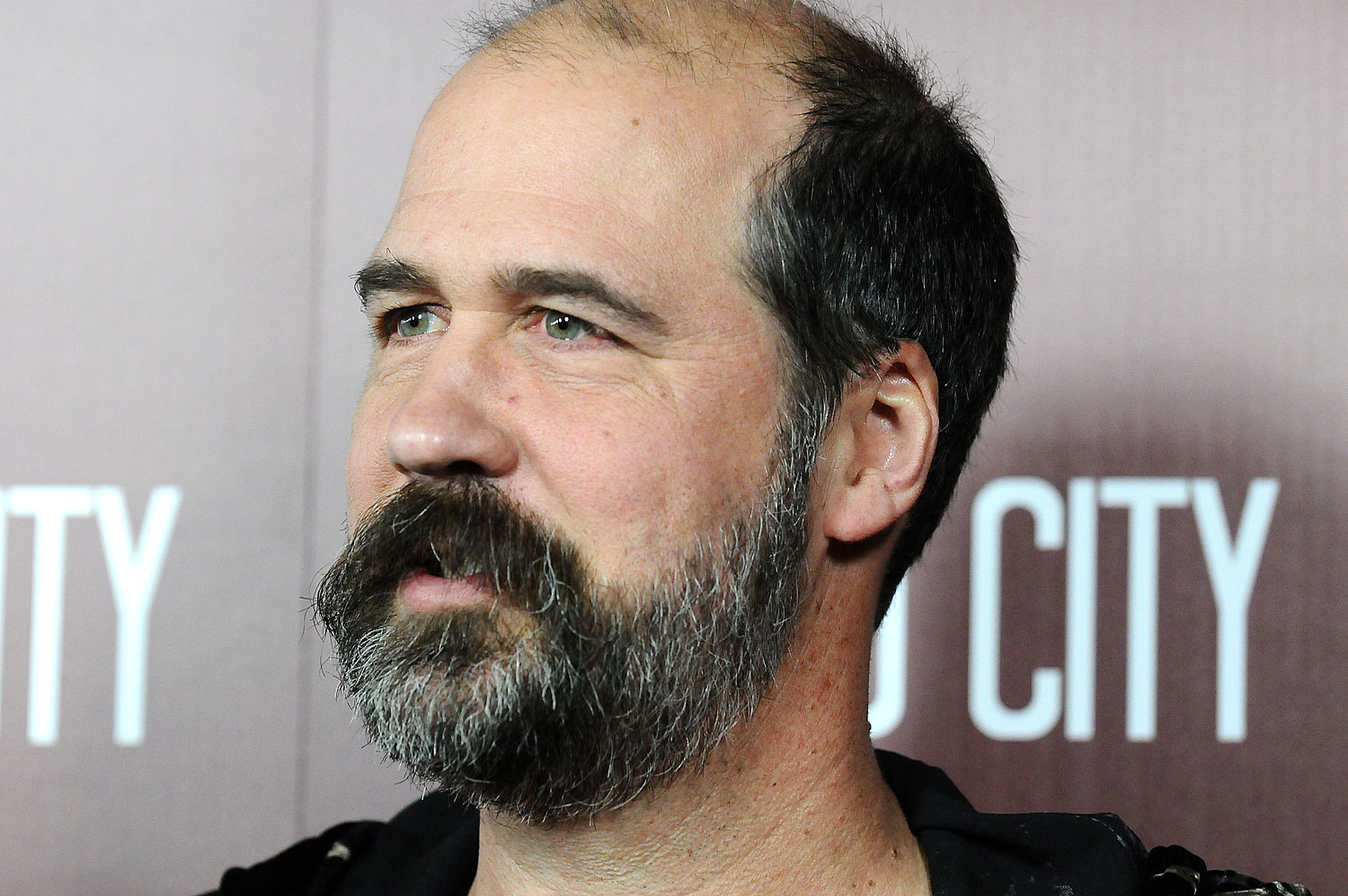

Krist Novoselic is the former bassist for Nirvana. Excerpted from Carl Wilson’s new book, Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste (Bloomsbury).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com