For many, higher ed and binge drinking go hand in hand. While the phenomenon may never go away, advocates say the public health campaign might be outdated, and the prevailing message that consuming too much alcohol is a sexual risk could be falling on deaf ears.

A new study from researchers at University at Buffalo, State University of New York, found that talking about the link between alcohol and cancer may be one of the better strategies to get college kids to reconsider their upcoming binge.

In the study, 116 students between ages 17 to 24 answered whether they thought binge drinking could increase cancer risk, how great they thought that risk was, and how much they were going to drink that month. Among the 88% of participants who thought there was a risk of alcohol-related cancer, the students who said the risk was significant were less likely to binge drink.

About four out of five college students drink alcohol, and about half of them report binge drinking, according to The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Binge drinking can lead to injury, sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancy, high blood pressure, liver disease, brain damage, and even cancers, according to the CDC. In 2009, about 3.5% of cancer deaths in the U.S. were alcohol related, and women who binge drink can significantly increase their risk for breast cancer.

While some colleges have cracked down on drinking with zero-tolerance polices, others have gone alternate routes to keep their students safe. “The most popular method is harm reduction, where you concentrate on behaviors that cause the most harm, like getting behind the wheel, vandalism, and sexual assault, and you try to mitigate that,” says Barrett Seaman, author of the book Binge: What Your College Student Won’t Tell You. “Complete enforcement of the law doesn’t work and is counter productive.”

Colleges across the nation have come up with plenty of innovative methods. Here are a few:

Free bartending classes

The Yale College Dean’s Office offers free bartender training and certification to all undergraduates–no matter their age. The classes teach students how to properly mix drinks, while focusing on alcohol safety. Students learn how to serve a stiff drink, but also the liabilities and laws around serving alcohol. “If students mix good drinks with the proper proportion of alcohol at their parties, they’re less likely to end up overdrinking than if they’re pouring bad liquor into solo cups,” Yale’s Alcohol and Other Drugs Harm Reduction Initiative writes.

Give students money for parties

Some schools, like Harvard University, offer grants so students can buy items other than alcohol for their parties. The goal is to encourage safe social events and reduce high-risk drinking on campus. The money from a grant can go toward a unique and fun alcohol-free party, or toward food and alcohol-free beverages at registered alcohol events. At the very least, there’s something for non-drinkers, and a better chance students aren’t drinking on an empty stomach.

Designated driver perks

The University of Virginia started a “Savvy Fox” program for their annual Spring Foxfield Races, a boozy horse-racing event. Registered designated drivers get free non-alcoholic drinks all day, pizza, and other swag.

Let students party, with alcohol, on campus

While many colleges maintain a dry campus policy, others, like Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, allow students who are over 21 and have undergone special training to host on-campus parties with kegs. The college designates certain areas on campus where parties can be hosted, and expects the hosts to abide by school and state rules. The hope is that by allowing parties with alcohol on campus, students won’t need to go to a bar and then get behind the wheel to get home.

“Social norming”

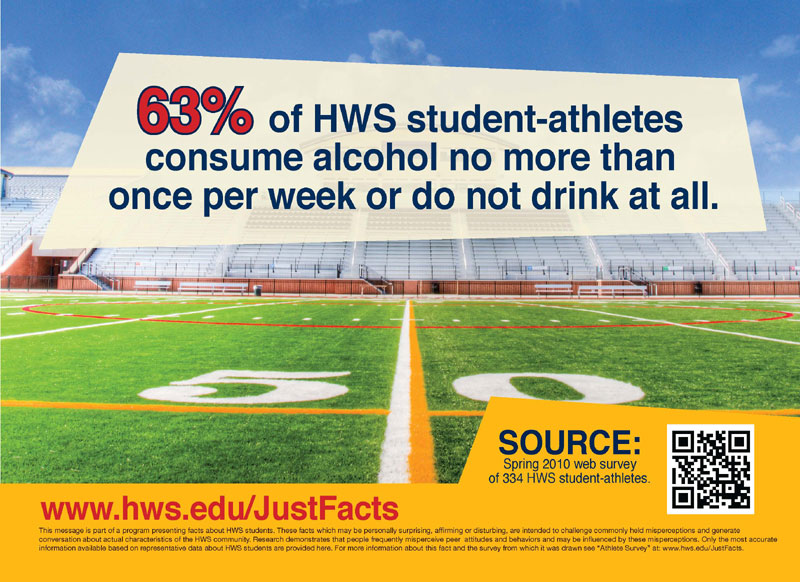

Professors H. Wesley Perkins and David Craig of Hobart and William Smith Colleges came up with “social norming,” based on the theory that the majority of people misperceive behavior norms and assume their peers engage in more risky behaviors than they actually do. To combat this, Perkins and Craig gathered data on the actual numbers of students who drink, smoke, and do drugs, and developed campaign materials that educate students on who is really partaking in such activities. The numbers are lower than people think.

“[This] works best on campuses where there is a significant disparity between student perceptions of how much their peers drink versus how much they actually drink,” says Seaman. “At larger universities, that disparity is likely to be wider than at small, tightly knit colleges where students can pretty much see how much and how often their peers are drinking.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com