This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Not so long ago (2011) the world was declared officially free of the cattle disease, rinderpest. As with the 1980 eradication of human smallpox, the basic weapon was vaccination. The rinderpest virus and measles virus are very similar, perhaps diverging from a common ancestor about 1,000 years back. We’ve had effective measles vaccines for around 50 years and the world could, and should, be rid of measles. But, apart from the problem of getting vaccine into war zones and other problems in very poor nations, we are nowhere near doing that. Why is that so?

The latest outbreak associated with visitors to Disneyland is just one of continuing, sporadic events all over the advanced world. Measles is very infectious. Classically, a young, unvaccinated person is taken on family vacation to a country where the virus is actively circulating, contracts the disease and brings it back to spread rapidly in (often) an “alternative” school where there are many other unprotected children. Such schools are often the choice for intelligent, well-educated parents.

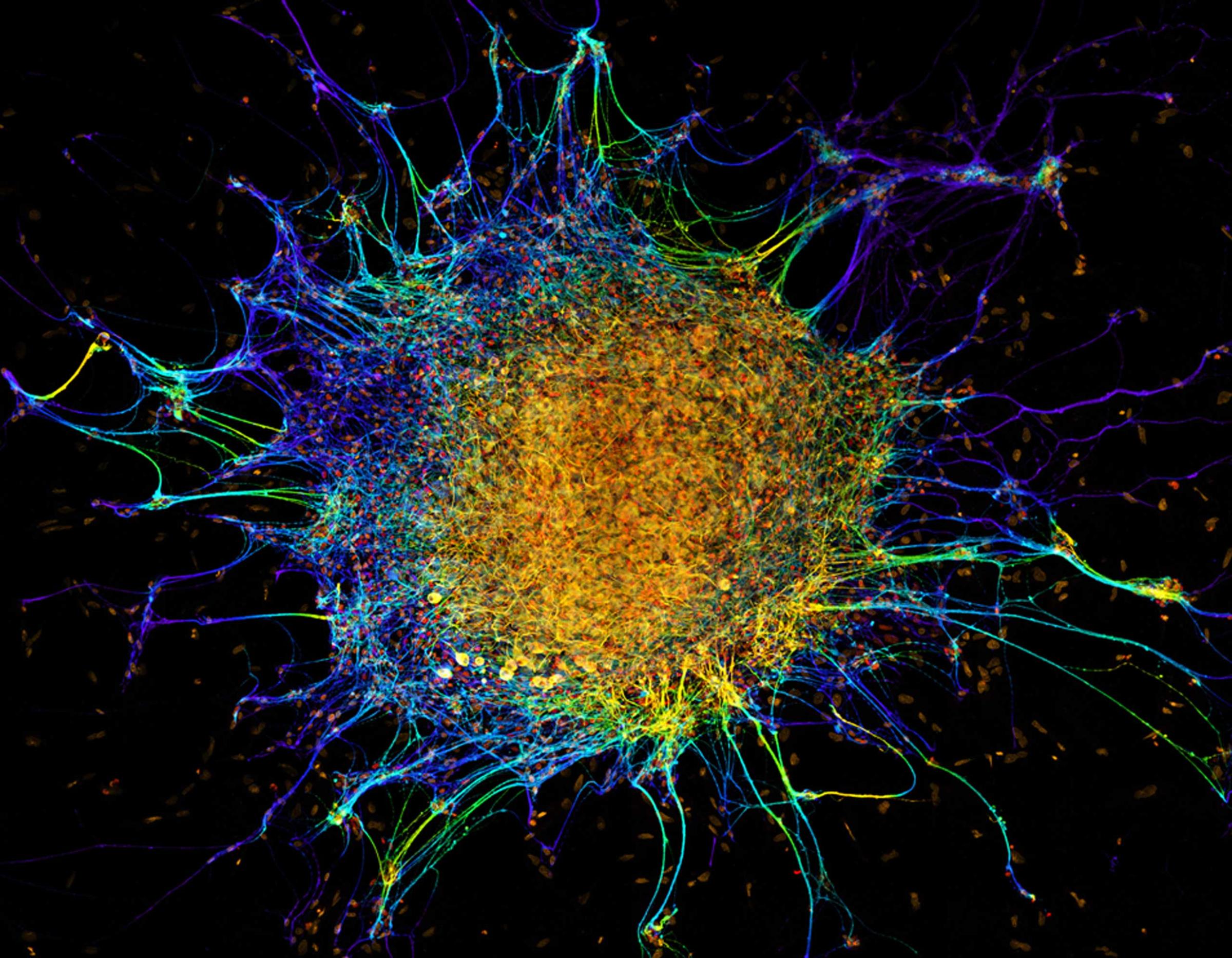

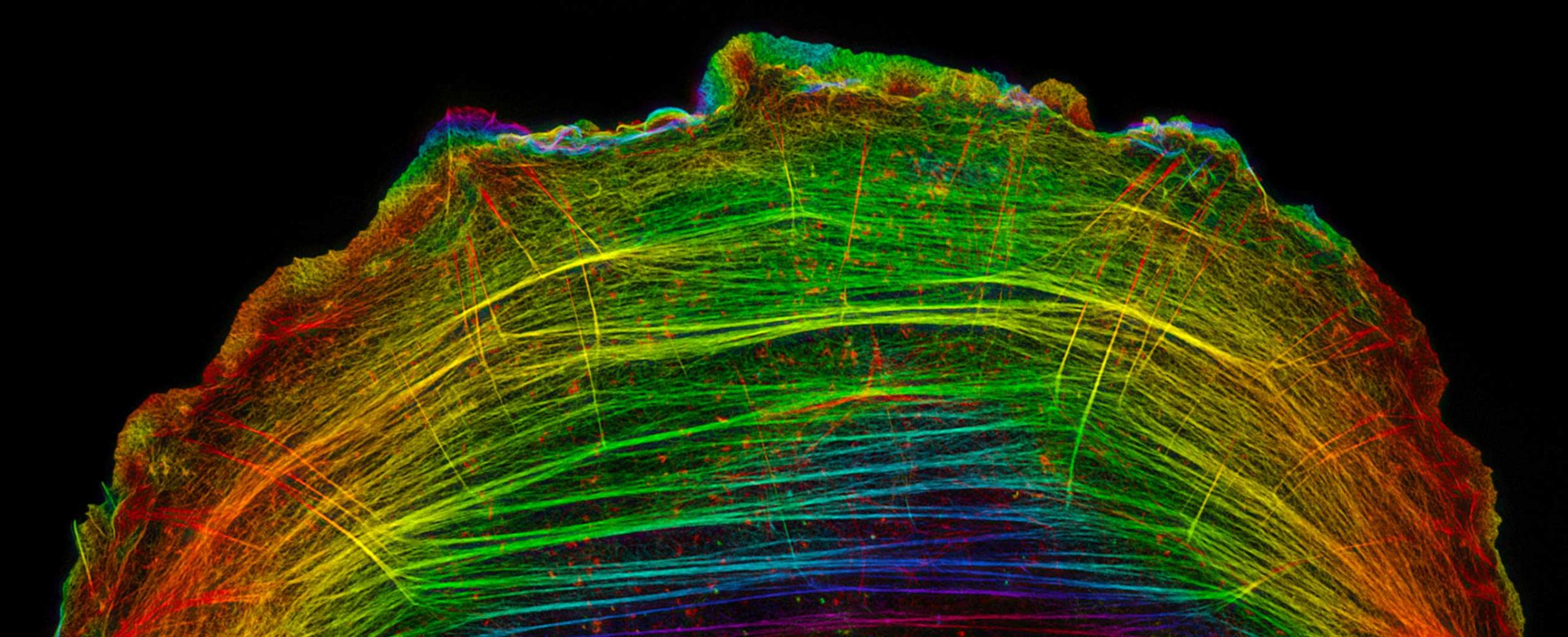

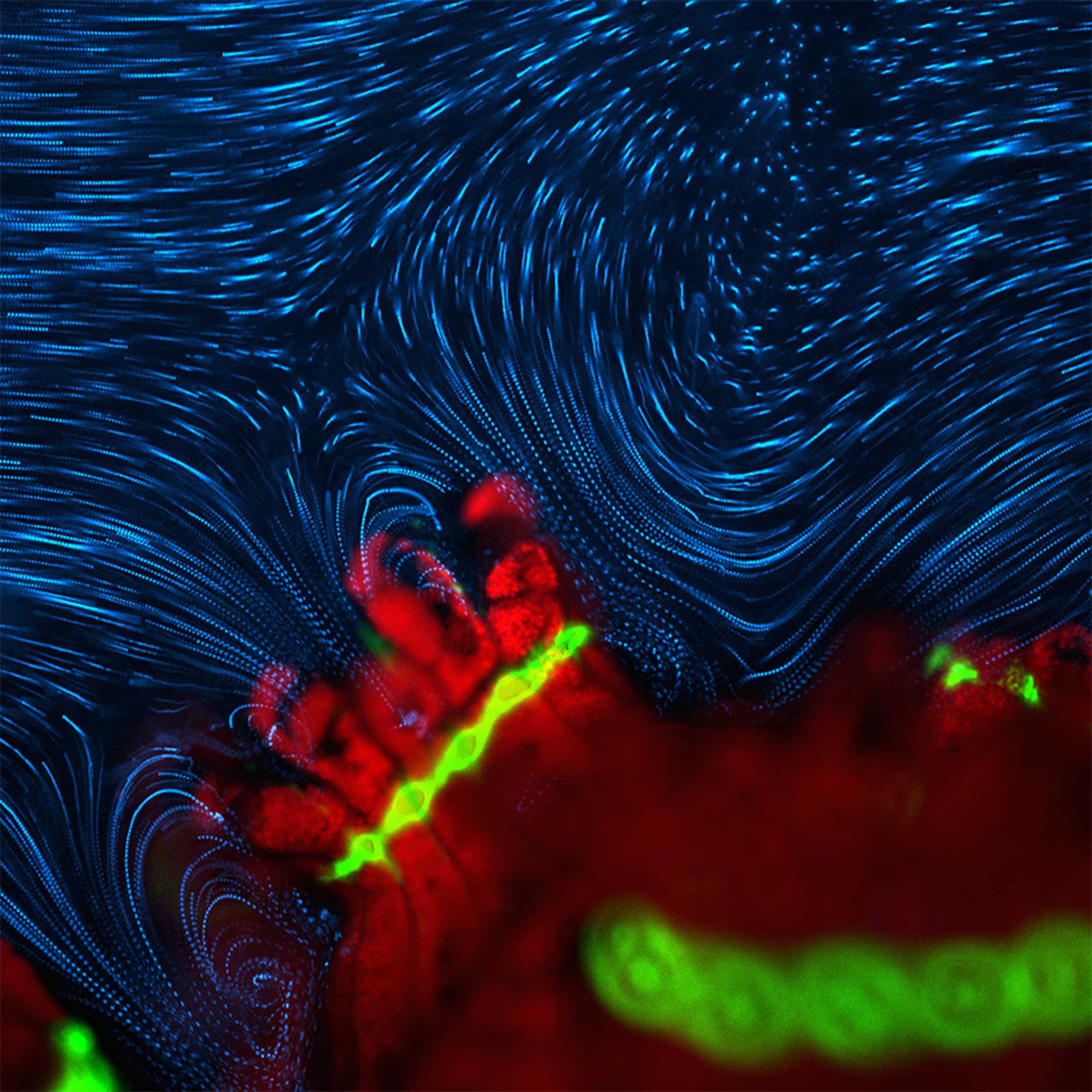

What’s happening with measles is a good example of the maxim that: “partial knowledge is dangerous.” In the main, people have a very limited understanding of infectious diseases. Viruses grow in cells and kill them. One virus particle is enough to initiate a full cycle of replication in what becomes a “factory” producing millions of progeny that are, in turn, released to go on and infect other cells. With influenza, the disease that I study, the successive cycles of infection, cell loss and inflammation are limited to the respiratory tract. That kills if the lung damage is sufficiently severe. With measles, though, the virus travels the body and can end up in any tissue.

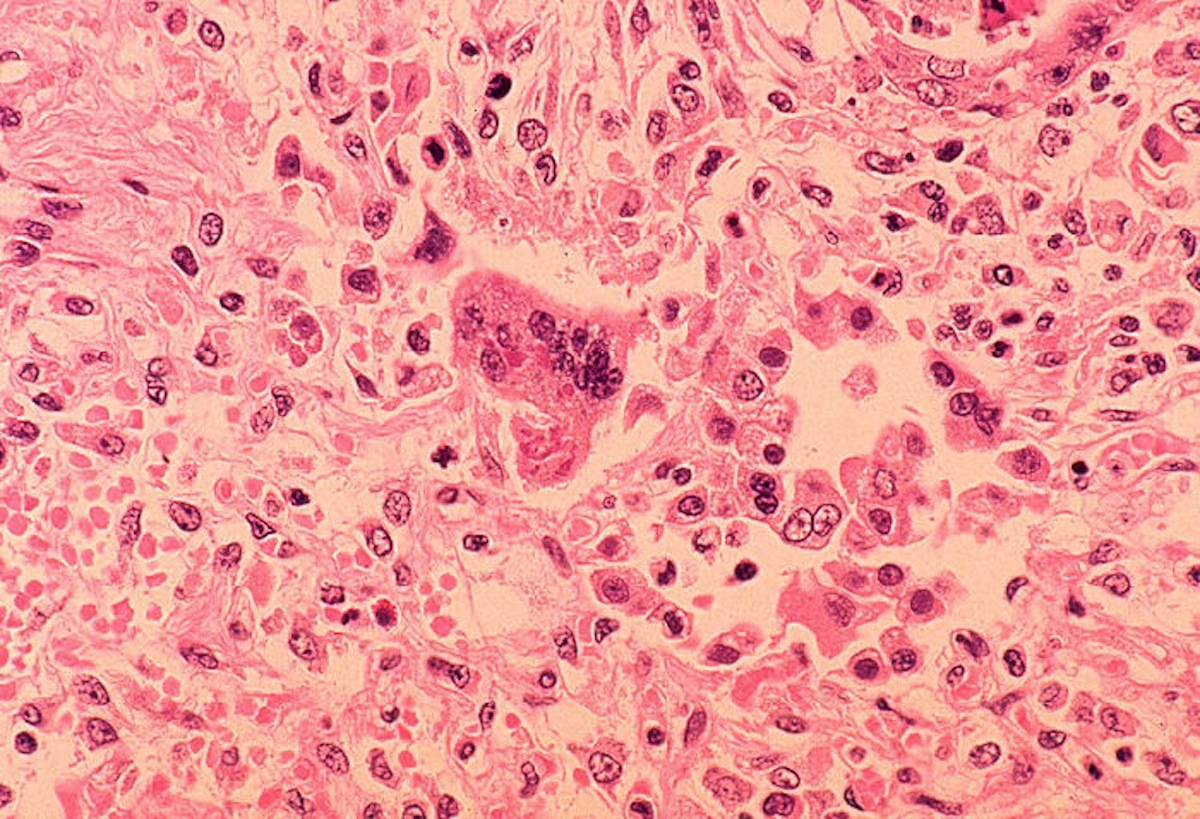

Most 1st world citizens and doctors who are under 60 have never seen a case of measles. Those who do know anything about this disease understand that the kids get prominent skin spots. Each one of those red “lesions” reflects a focus of virus growth. The measles virus invades via the oropharynx, multiplies there and is then disseminated via the blood. The effects in the skin are obvious, but we don’t see what’s happening in the lung, the brain, the middle ear and elsewhere. The measles sequelae can include long-term hearing problems, persistent lung damage and (fortunately rare) the terrible disease subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). In SSPE, a defective measles virus “hides out” in the brain, then suddenly re-emerges in adolescence. A fit teenager can suddenly go into a coma and die. SSPE disappeared with the widespread use of the measles vaccine. Nobody wants to see it return.

The measles vaccine is an “attenuated” virus strain that undergoes limited replication, infects few cells and does not disseminate widely via the blood. Given that the recommended immunization schedule has been followed, it provides long-lasting immunity.

So why does this vaccine get such a bad rap with some parents? Apart from a tendency of “empowered” adults to disregard medical advice and say “I will decide what is given to my child,” there are claims that injecting the measles, mumps rubella (MMR vaccine) is associated with the development of autism. This appeared in a 1998 paper by Andrew Wakefield and 12 others published in the prestigious British journal, The Lancet. The data set was just 11 cases, and the correlation was with MMR, not with the measles vaccine as such. There has been no confirmation, despite massive, international efforts to replicate the Wakefield et al findings. Major issues have been identified with the original Lancet paper, which has been retracted by the authors, excepting Dr. Wakefield. Apart from the tragedy that children are now needlessly contracting measles, the claim distracted those who are seeking a cause for autism, particularly some in the patient advocacy groups.

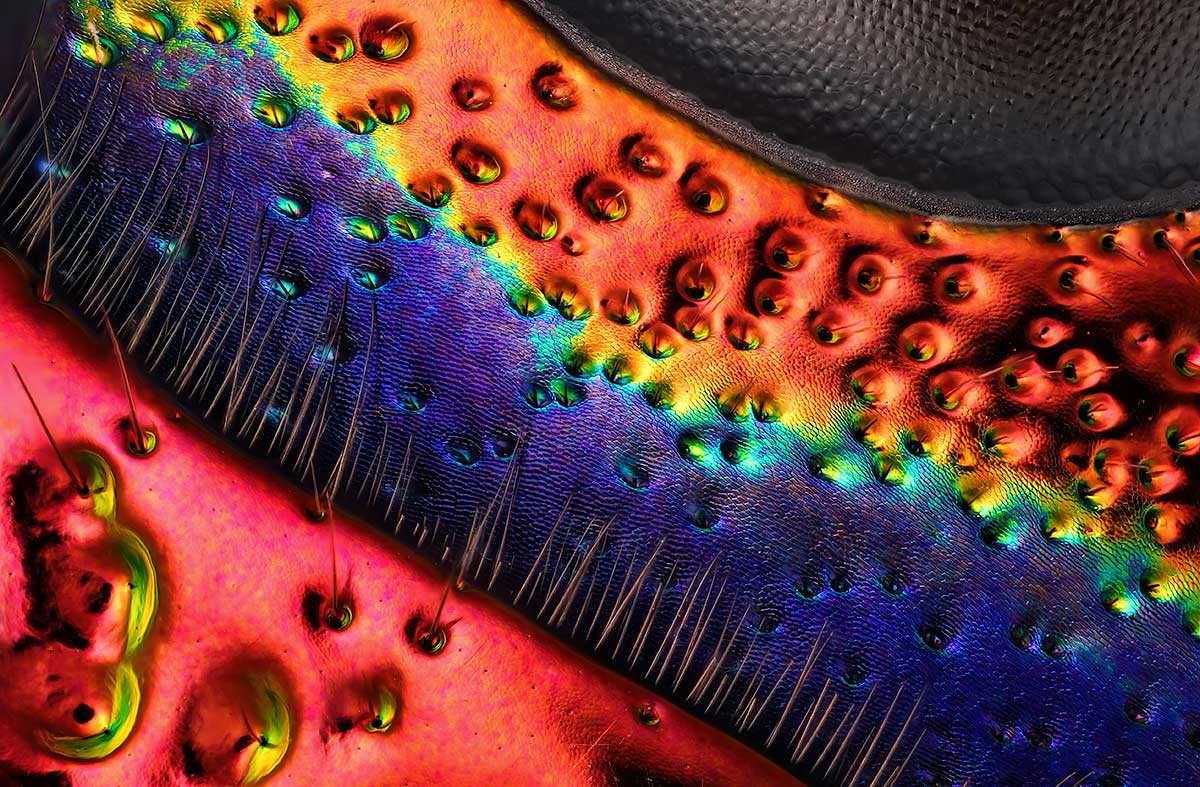

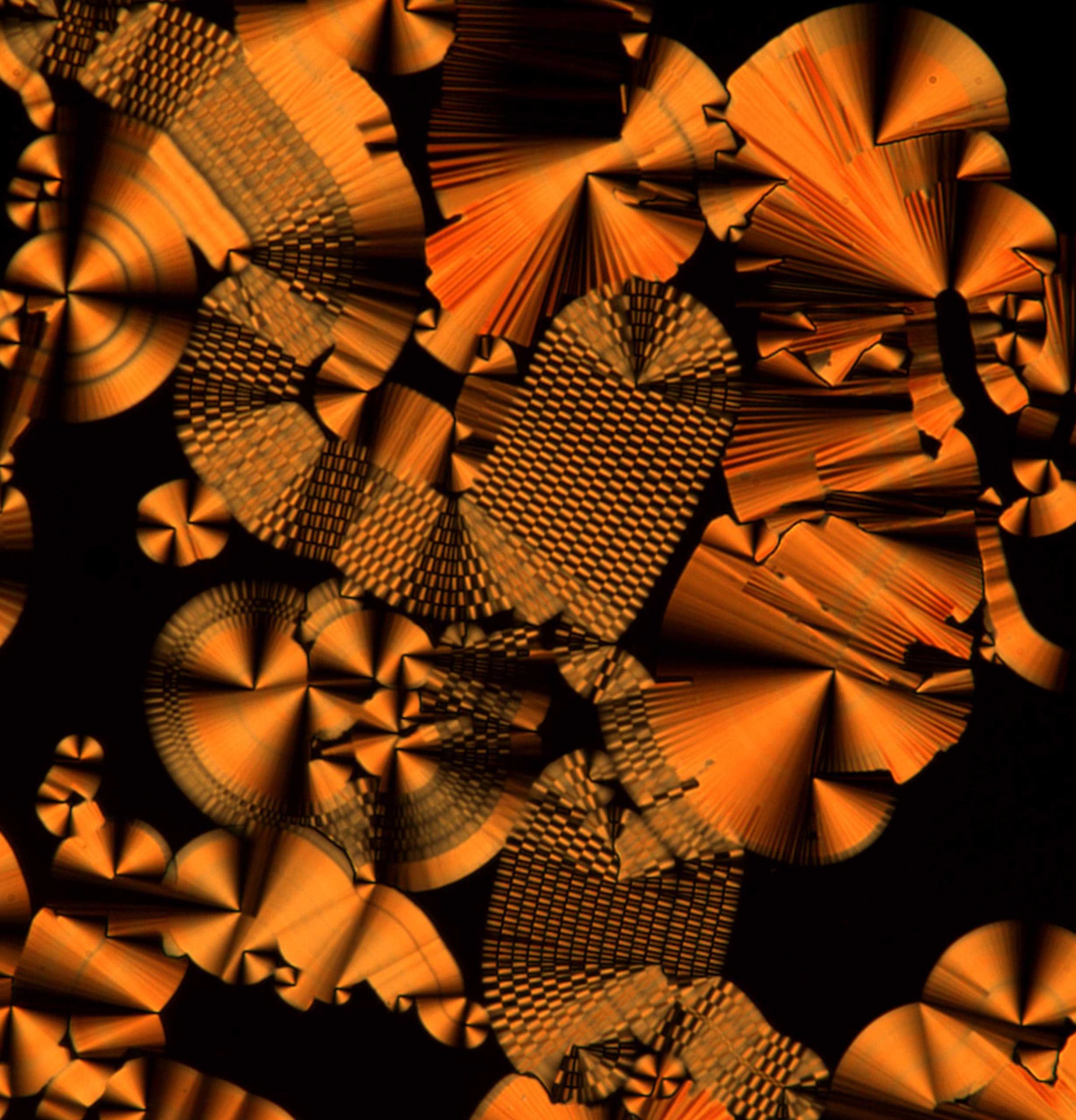

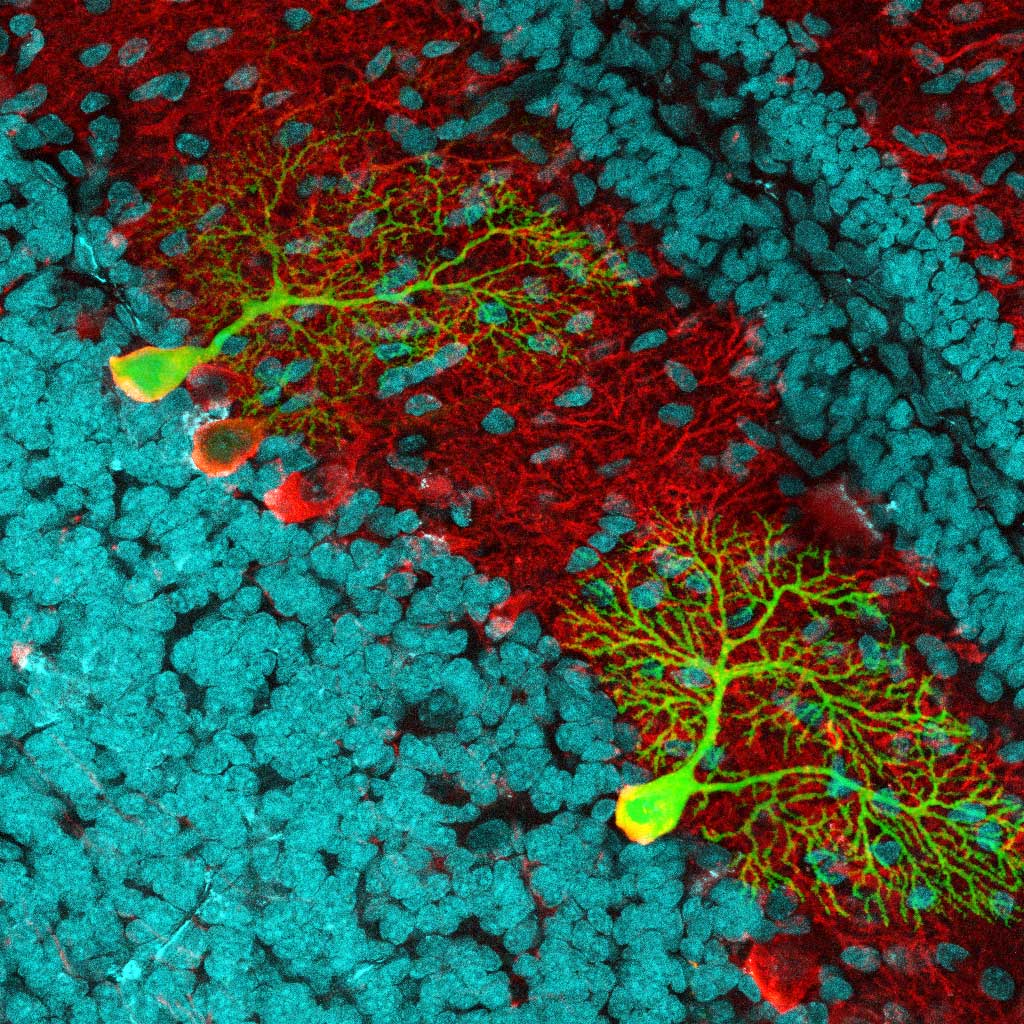

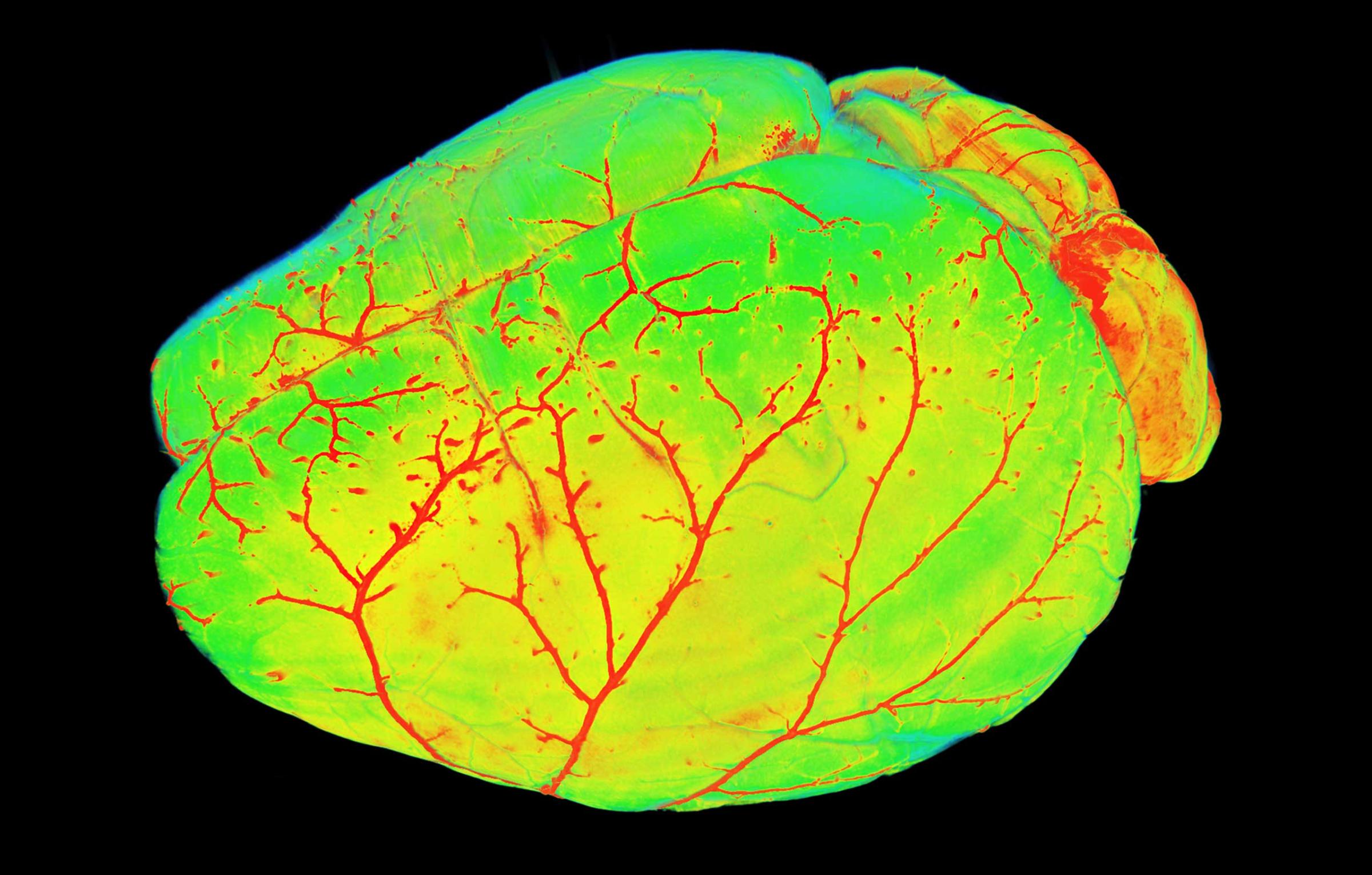

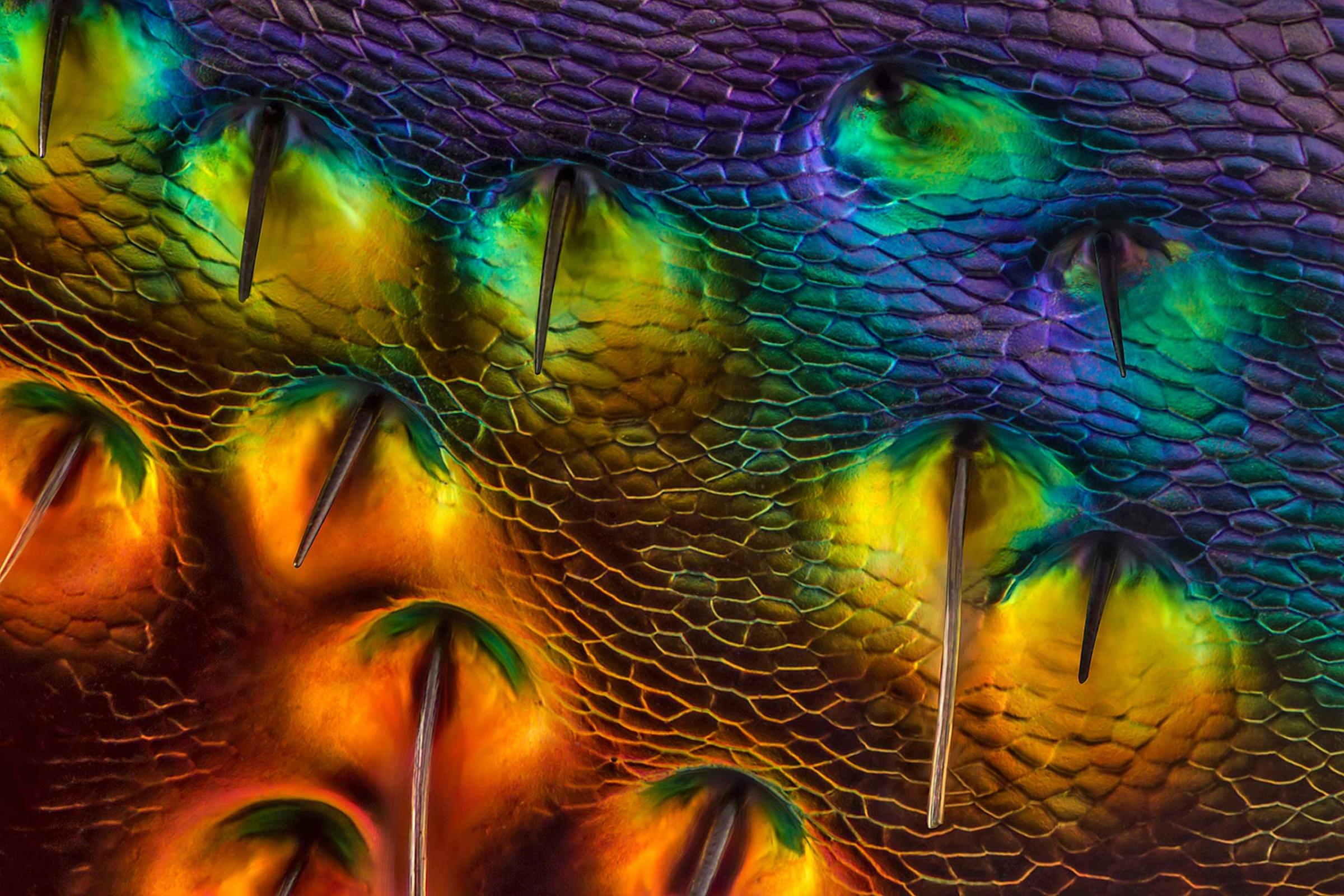

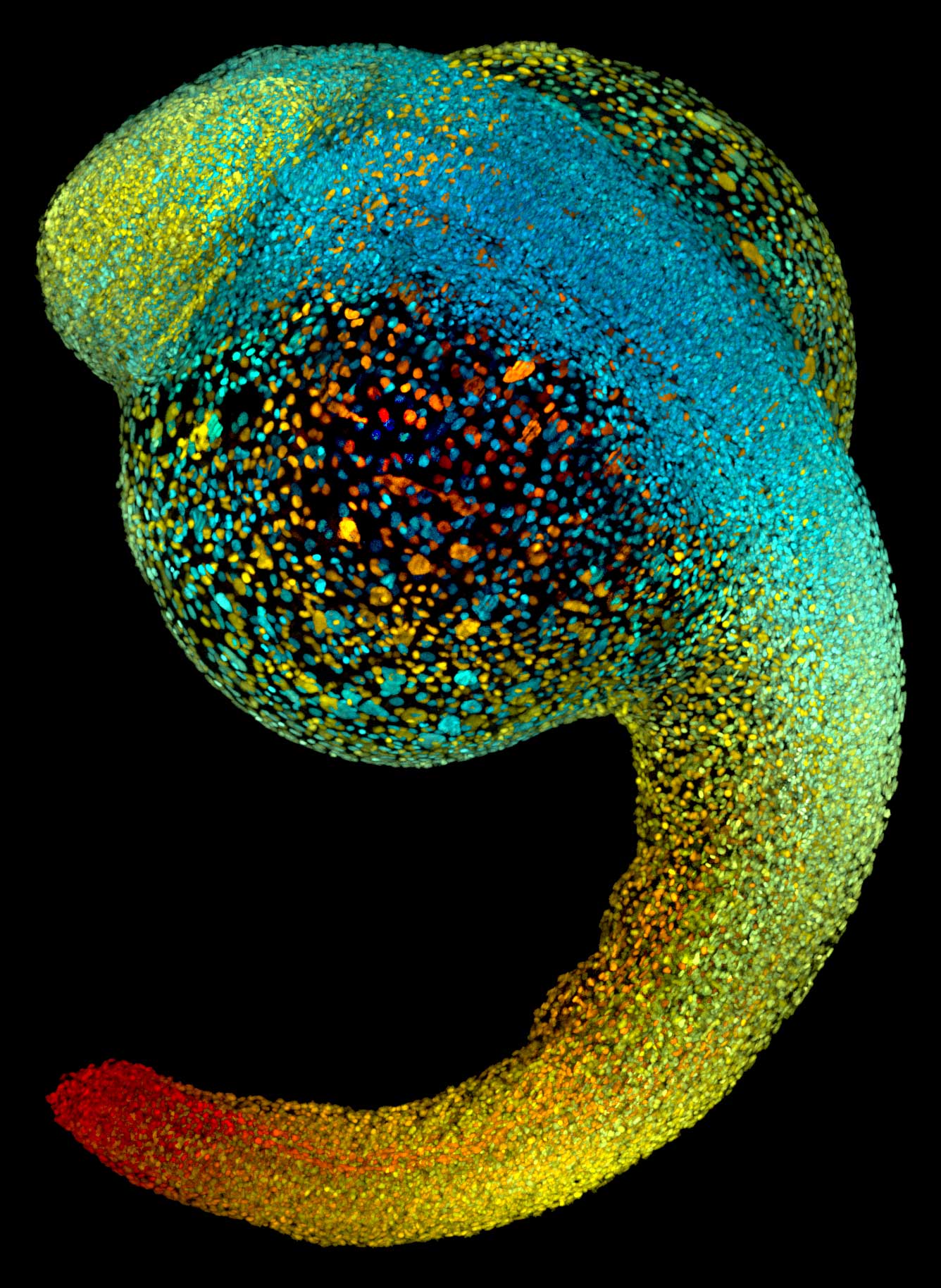

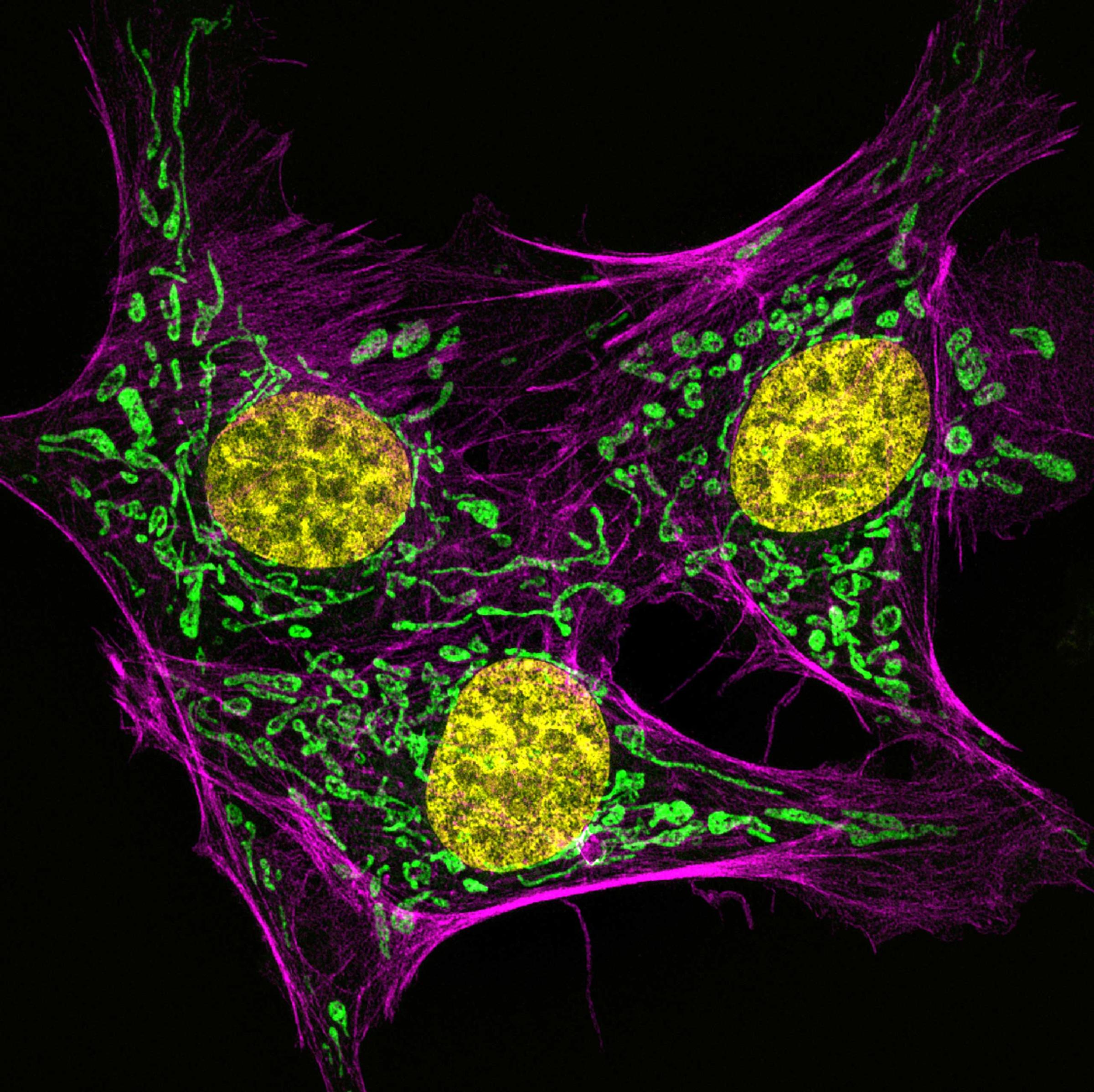

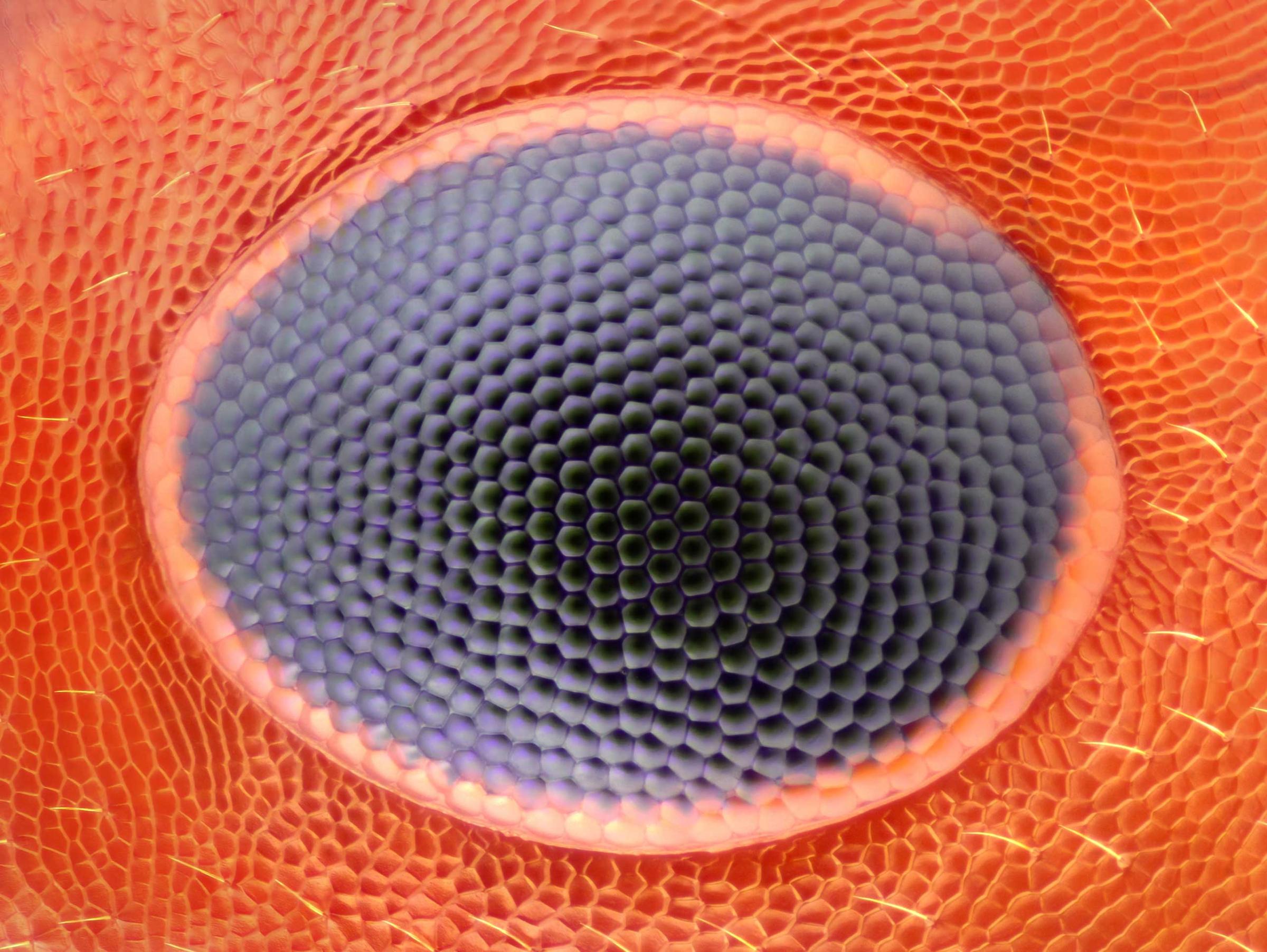

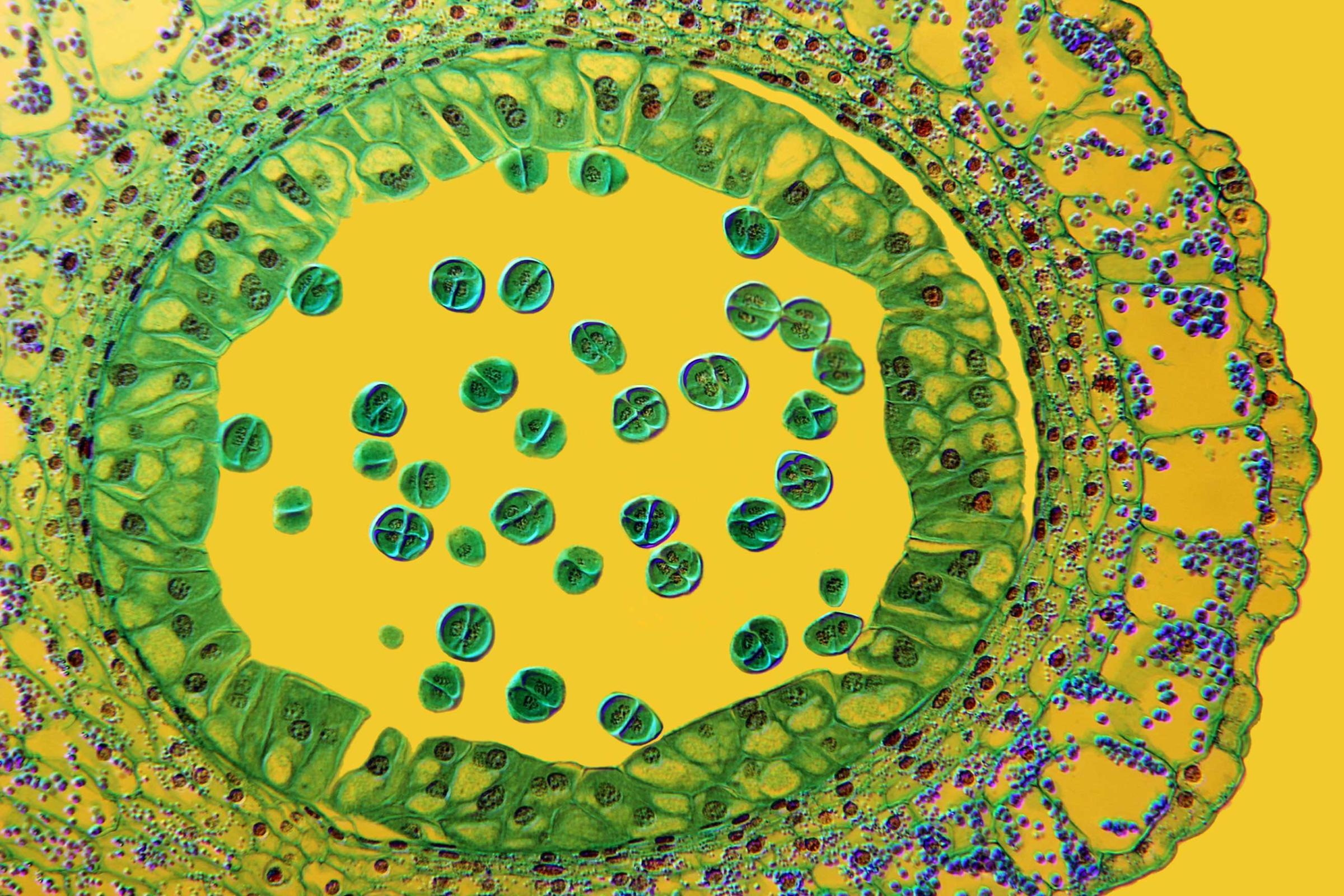

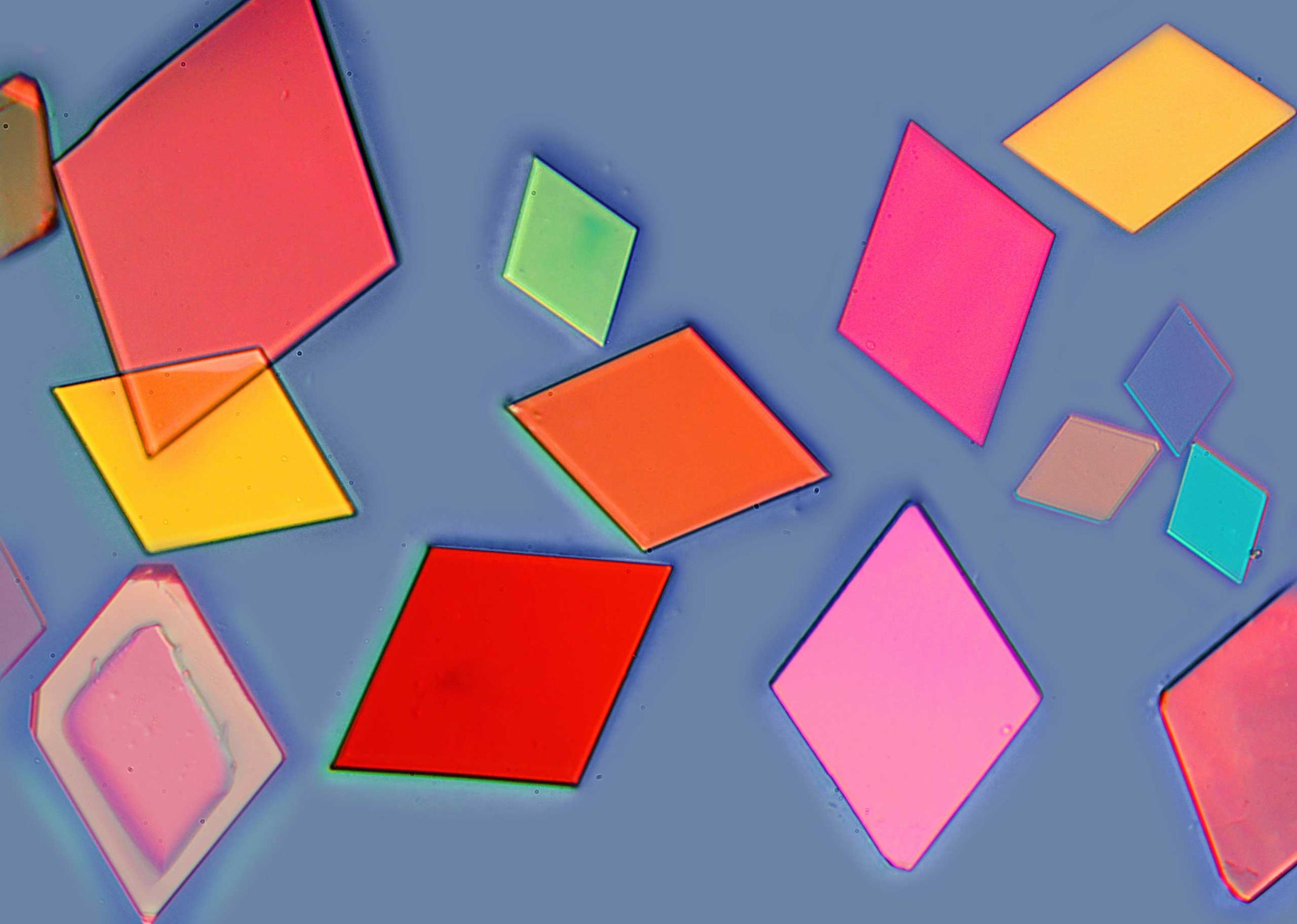

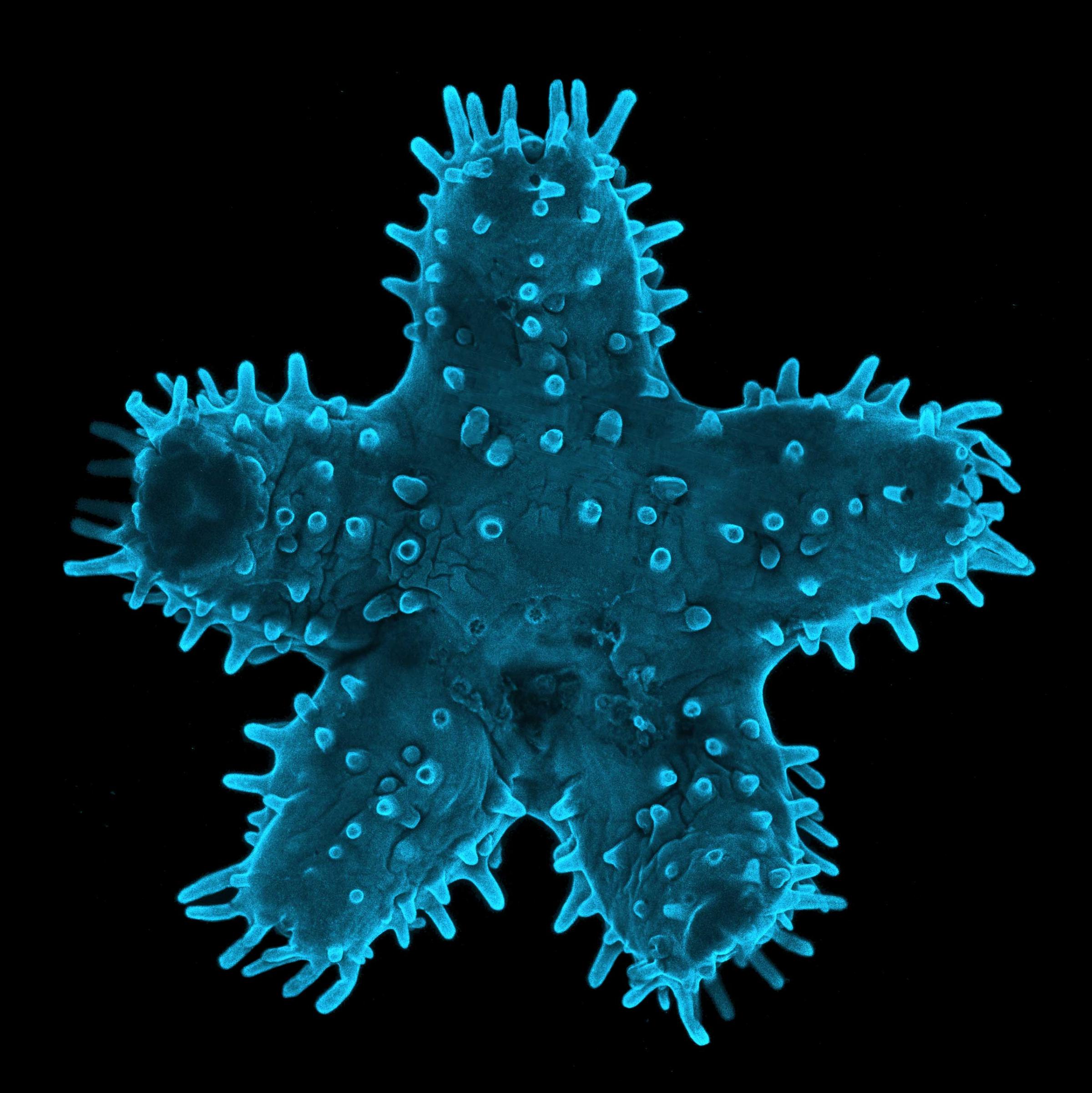

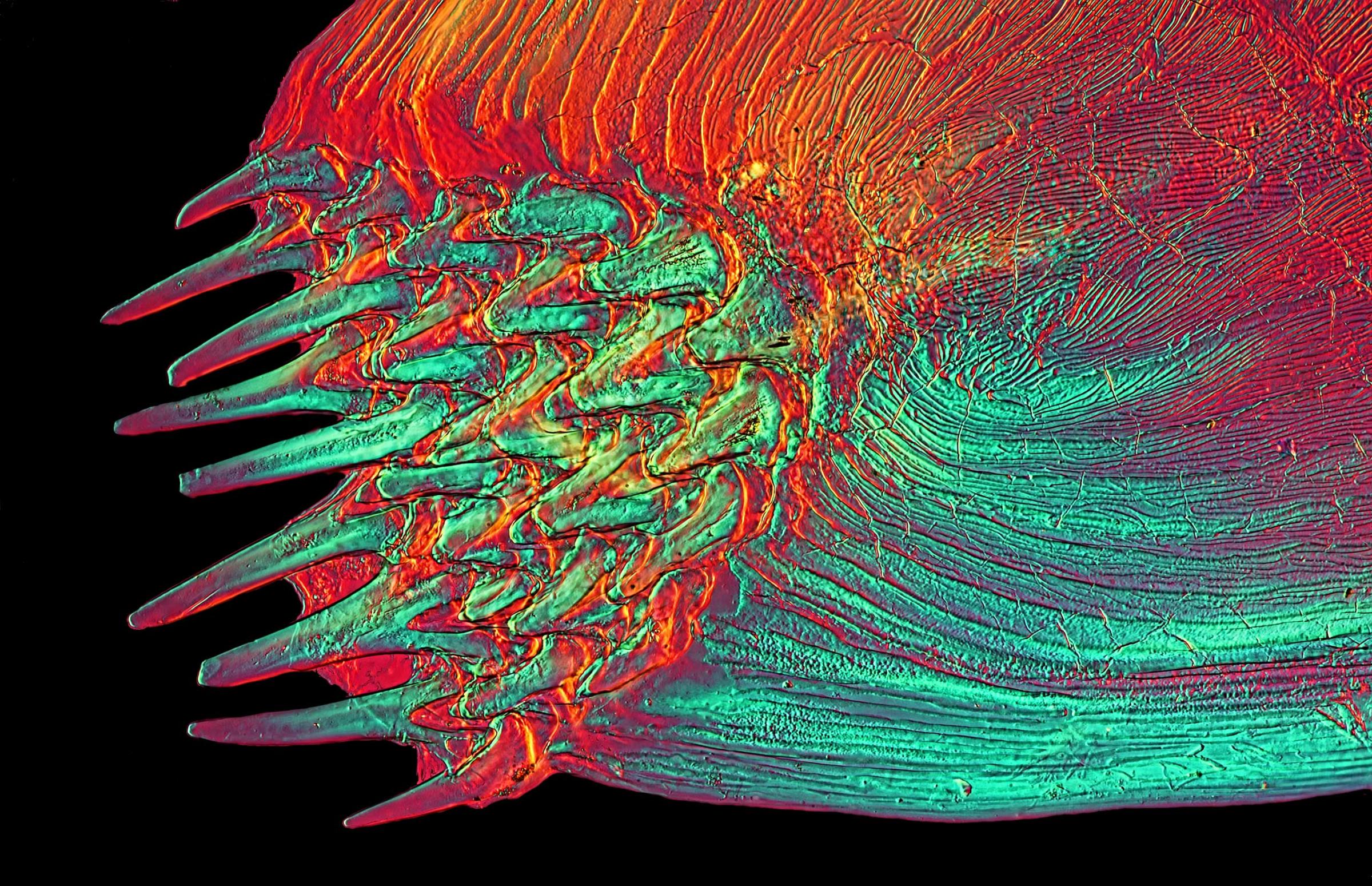

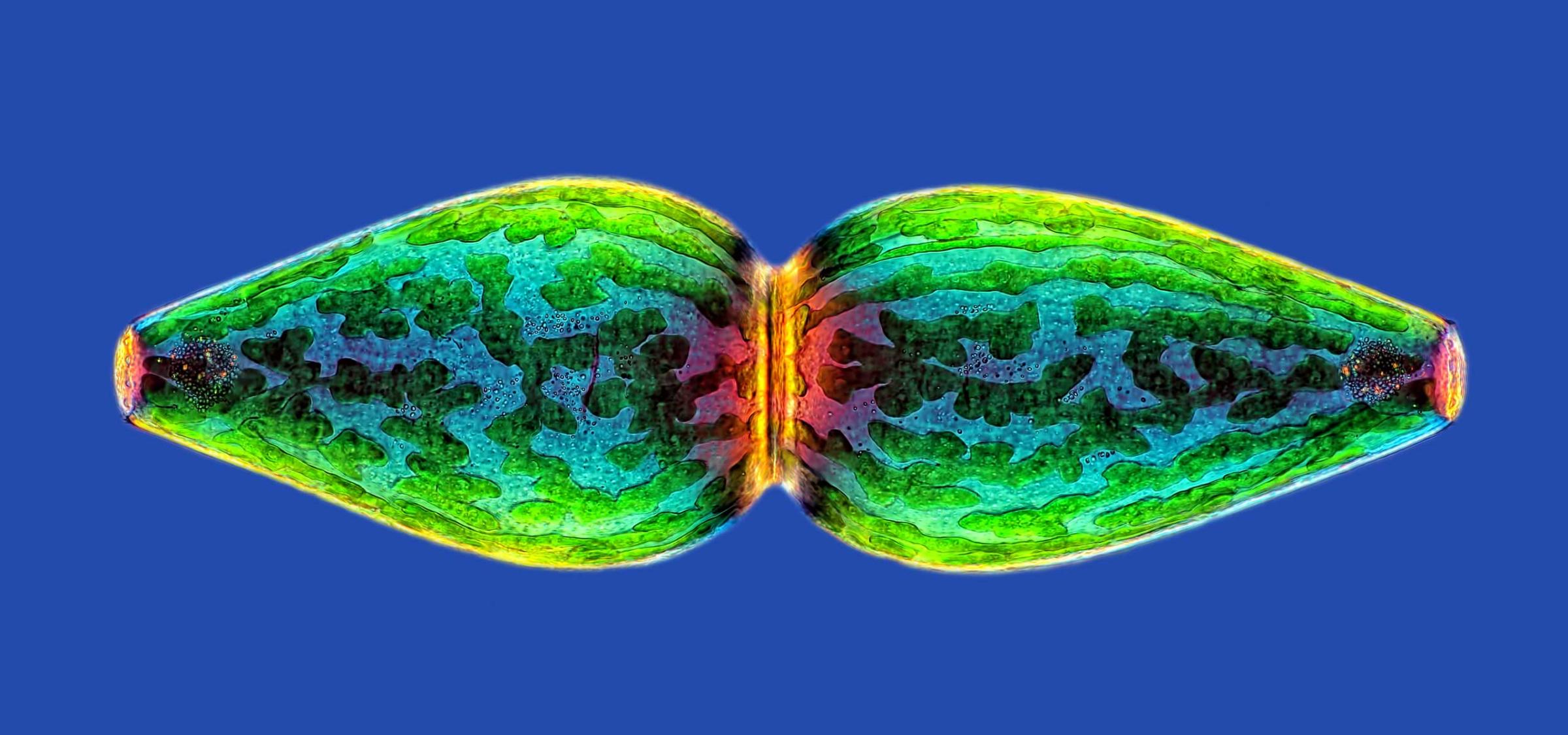

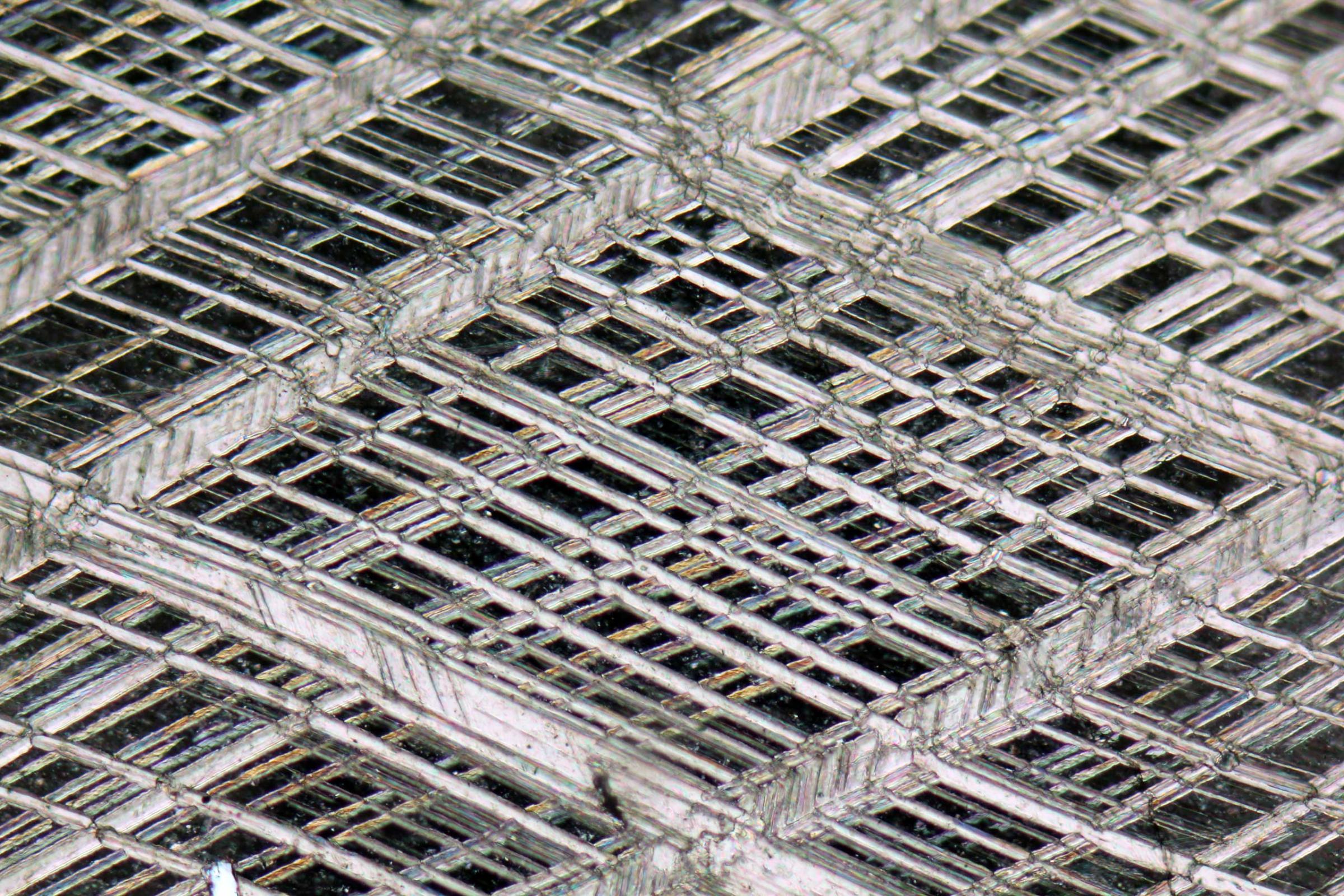

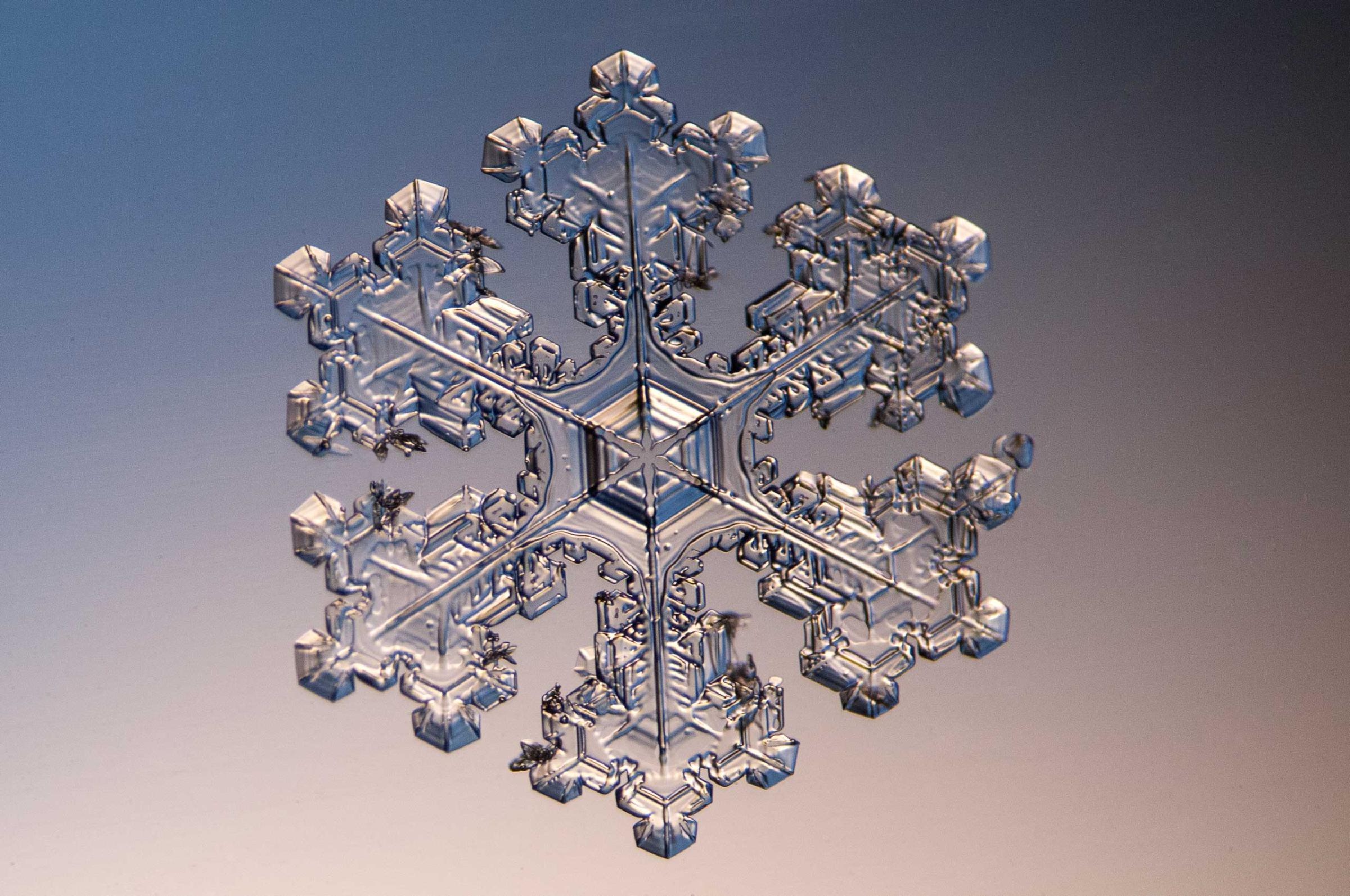

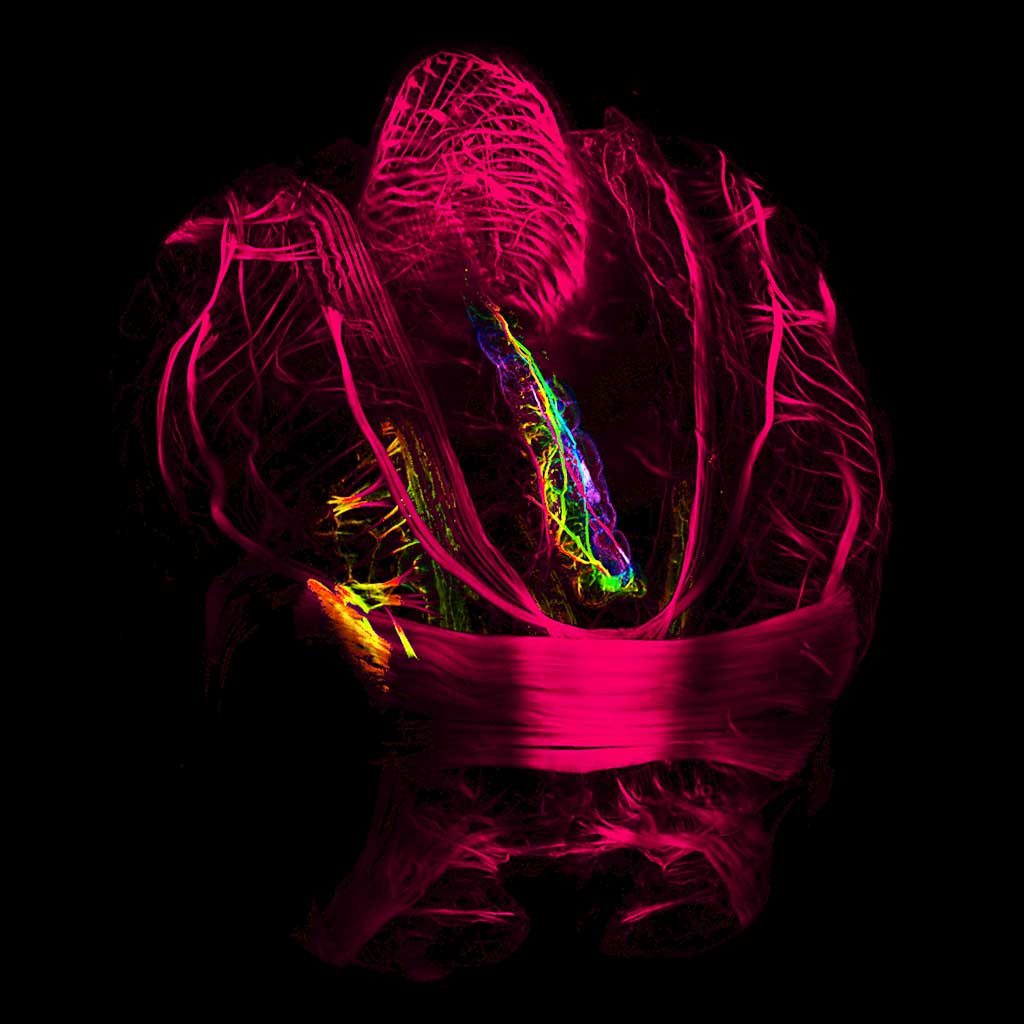

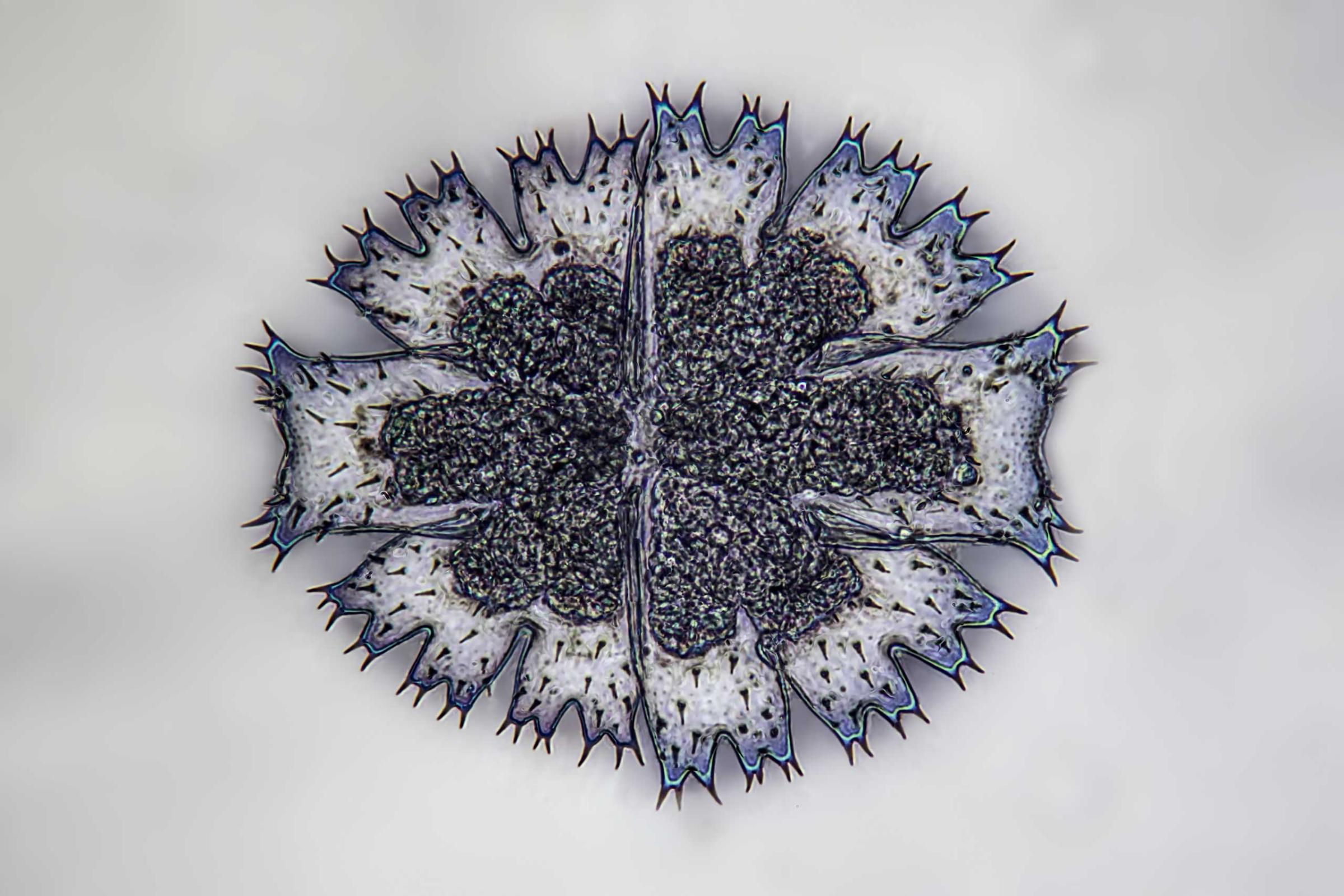

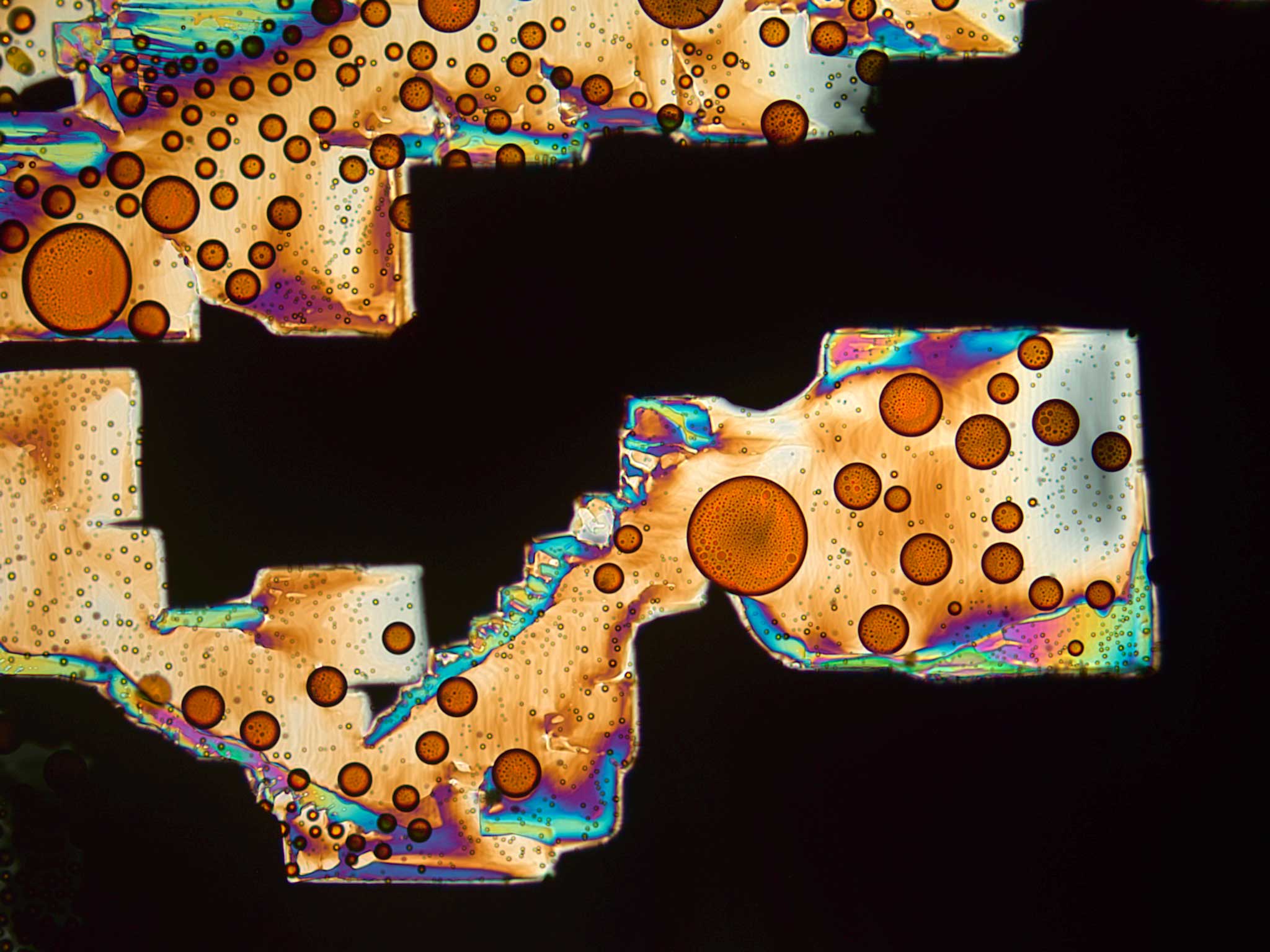

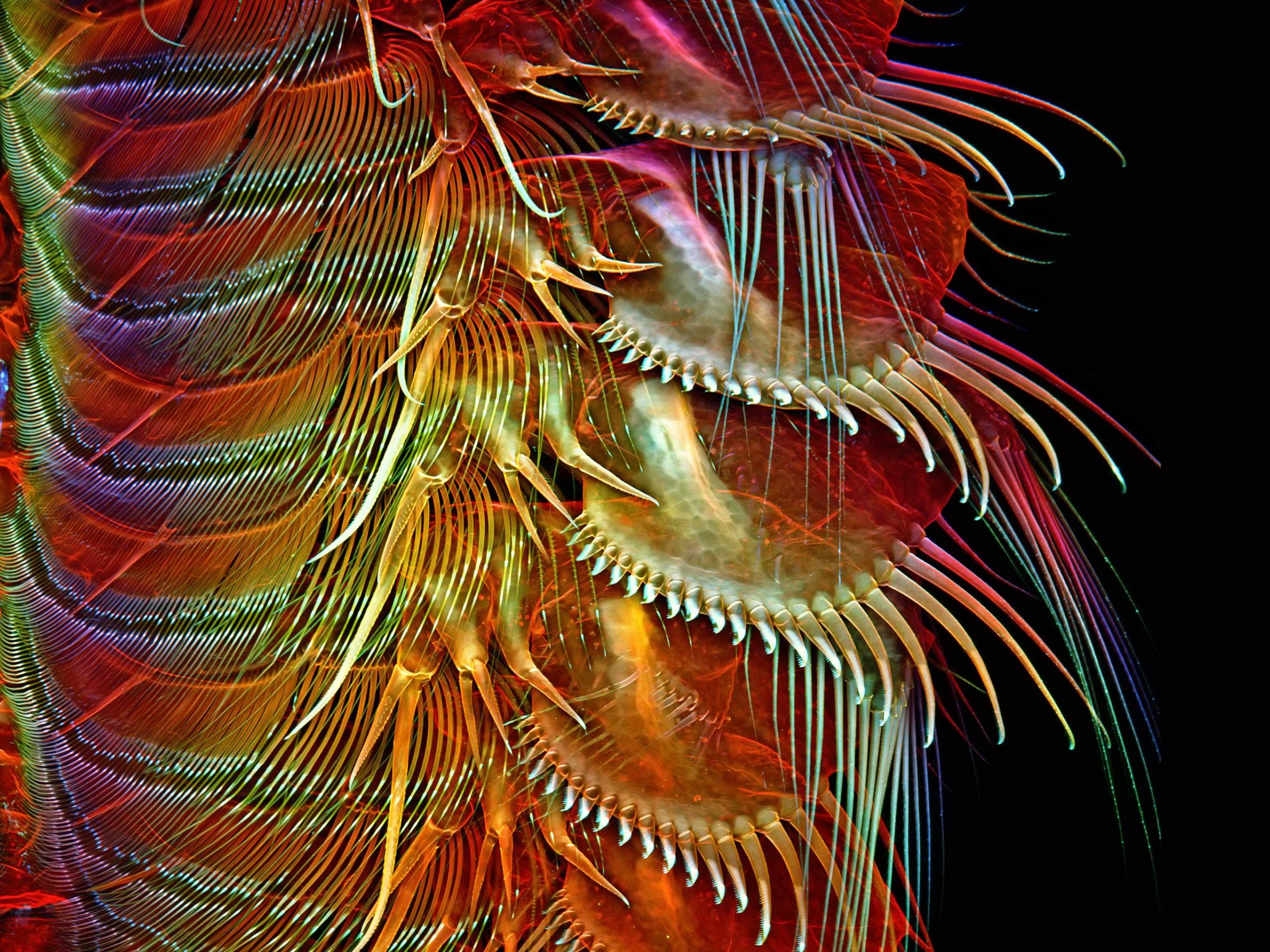

See 40 Stunning Images Captured Through A Microscope

Why was this underpowered Lancet study so readily accepted? The thought that you might cause your child to develop autism is obviously horrific, and the problem with autism is that it often emerges around the age that children are receiving the standard vaccines. Listening to people arguing this case, it’s obvious that people will connect anything bad that happens to their kids back to vaccines given weeks, or even months previously. And the fact of the matter is that vaccination, like any medical procedure, has to be looked at through the lens of relative risk. There was a recent situation in Australia where an influenza vaccine was too “reactogenic,” causing fever and convulsions in a few very young children. The vaccine was quickly withdrawn and replaced by a safer product, with the event being thoroughly investigated by the US FDA and by the relevant Australian authorities. There were similar issues way back with whooping cough vaccines, which have been replaced by much “cleaner” products, though they are less effective in the immunity sense.

If, in reading this, you want to find out more, go online and watch the excellent NOVA documentary: Vaccines: Calling the Shots. Made by the Australian film-maker Sonya Pemberton, it first aired “down under” as Jabbed and was modified for a US audience. Then, I did my utmost to write an easily understood chapter on infection and immunity and how vaccines work in my recent (2013) Q&A book, Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know.

We all realize that parents want to do their best by their kids. That involves, though, not believing what some dubious and ignorant “celebrity” says on TV, but doing your utmost to understand the evidence and find out what is real. There is no virtue in ignorance, especially in deliberate ignorance that can compromise the wellbeing of children. Measles is highly infectious, and vaccination is a collective responsibility. According to the World Health Organization, some 145,700 children died of measles in 2013, with most fatal cases being in babies who are too young to be vaccinated and/or those with poor nutritional status. Who would want to be responsible for killing a vulnerable child?

Peter Doherty shared the 1996 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for illuminating the nature of the cellular immunse defense. He is a member of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Melbourne, Australia. You can find him on Twitter @ProfPCDoherty

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com