When I was 12 years old, I became an avid reader, my bookshelves stuffed with paperbacks like Jackie Collins’ Hollywood Wives, Sidney Sheldon’s The Other Side of Midnight and Harold Robbins’ Dreams Die First. Much as I loved reading about groupies and spies and Hollywood wives, and drug addicts and murderers, I was not one of them. I hadn’t even French kissed. Though some of the girls at my school were already sexually experienced, in spite of my racy reading, I was not. I wasn’t much into boys, at least not ones who existed off the page of a juicy book.

I think about teen-reader me a lot when I hear about adults bemoaning the dark material in Young Adult books. (Interestingly, I rarely meet these folks; only read about them.) Because the concerns seem partially predicated on this idea that you become what you read. By that logic, I would’ve become a cocaine-snorting groupie years ago, or a lunatic or a murderous Russian. Because by 10th grade, it was Vonnegut and Dostoyevsky I was obsessed with. Partly because by this time, I’d become a wee bit pretentious. But partly because the kinds of books I would’ve loved to read weren’t being written yet.

The other concern with dark YA seems based on a worry that these intense stories—which sometimes deal with issues like self-harm and addiction and abuse and even death—could irrevocably damage fragile minds.

Huh.

I’m never all that sure what makes a book “dark” in the first place. It seems to vary with seasons, or the trends. Are dark books the ones that allegorically explore serious subject matter, like warfare (The Hunger Games) or the human capacity for destruction (Grasshopper Jungle)? Or at they the ones that reflect our actual world, including the capacity for human cruelty and kindness (The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian) or the messy stuff of human mortality (The Fault In Our Stars)?

Because if those books are dark, and that’s a problem, I’m confused. Are these not the same subjects young people are encouraged to engage in at school, by reading the newspaper, or canonical texts like The Iliad (warfare) or Macbeth (the capacity for self destruction) or To Kill A Mockingbird (kindness and cruelty) or A Farwell to Arms, all Emily Dickinson poetry (that messy morality business)?

But for a moment, let’s put the question of whether books are dark aside. For a moment, let’s just say that some YA is dark. And….so what?

Literature swims in the murkier waters of the human condition. Conflict and matters of life and death, of freedom and oppression—it is the business of books to explore these themes, and the business of teenagers, too.

New brain mapping research suggests that adolescence is a time when teens are capable of engaging deeply with material, on both an intellectual level as well as an emotional one. Some research suggests that during adolescence, the parts of the brain that processes emotion are even more online with teens than with adults, (something that will come as absolutely no surprise to any parent of a teenager). So, developmentally, teens are hungry for more provocative grist while emotionally they’re thirsty for the catharsis these books offer. Of course teens are drawn to darker, meatier fare. The only surprise about this is that it’s a surprise.

There may be another reason for the appeal. Adolescence is a time when teens are statistically more likely to come into harm’s way, and thus more likely to witness harm among their peers. According to the National Institutes for Mental Health, teens between 15 and 19 are about six times more likely to die by injury than people ages 10 to 14. Is it any wonder that they want books to help process what they’re experiencing around them, often for the first time?

That increased death rate, however, is a chilling statistic, particularly if you’re a parent. Seen through that lens—the fear of something terrible befalling a child—the wariness about dark YA begins to make more sense. Because if your child doesn’t read about death, about abuse, about rape, about suicide, then these terrible things won’t happen to him or her.

But that is a form of magical thinking, and no matter how well intentioned, it’s wrong. Because books don’t create behaviors. It’s possible they reinforce existing behaviors, but those behaviors are already present, not created by a novel. A novel won’t turn a bookish drama geek into a promiscuous drug abuser any more than it will turn a promiscuous drug abuser into a bookish drama geek, unless the seeds of those transformations were already planted.

What books can do, however, is reflect an experience and show a way out of difficult, isolating times. It’s why Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak has become such a touchstone, giving young women a voice to speak about sexual abuse, or Sherman Alexie’s Part-Time Indian has been a life raft for young people who can’t see their way out of existences straightjacketed by addiction and deprivation. I don’t believe that books, YA or otherwise, have the power to save lives. That’s a bit too grandiose for my thinking, but seeing your experience, your sometimes difficult experiences, reflected can be a powerful incentive to reach out and get the help that could indeed save a life.

I suspect that most teens who read and love “dark” YA have little in common with the struggling characters they relate to. Whenever I ask teenagers why they’re drawn to books like my novel If I Stay—in which the main character loses her family in a car accident—they overwhelmingly say the appeal is seeing an ordinary teen forced into an extraordinary circumstance. Reading about everyday fictional teens rising to the occasion (and, spoiler alert, in YA books they almost always do) allows actual teens to imagine themselves doing the same, within the lower-stakes conflicts and contexts of their own lives. This is empowering, and hopeful, words that I would use to describe many YA books. Even the dark ones. Especially the dark ones. These “dark” books may seem to be about death, about illness, about pain, but really they are about life. The kids get that, even if the adults sometimes, do not.

Some of my favorite “dark” YA books:

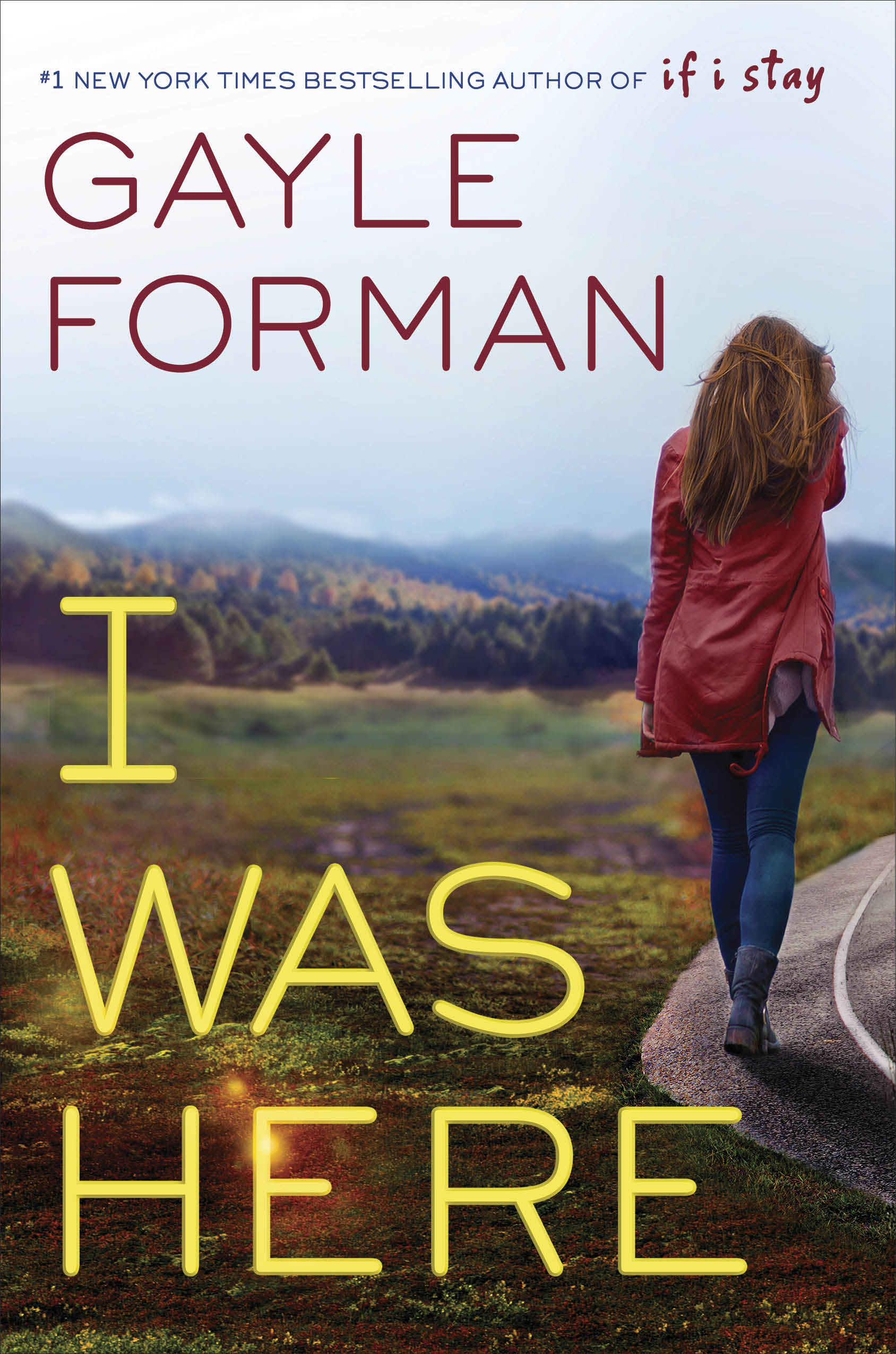

(Gayle Forman’s best-selling novel If I Stay was made into a motion picture in 2014. Her latest novel, I Was Here was published in January 2015. )

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com