As the glaring winter light filters through the sheer curtains that line his Upper West Side apartment, Bruce Davidson looks around his vibrantly adorned living room. He’s trying to decide between the tan zebra-patterned couch, the green sofa with leopard print throw pillows or one of the assorted seats that surround the oversized coffee table. He finally settles in a simple wooden chair and begins, “It’s a long story. I was stationed in France, and in my guts were pictures of miners taken by Robert Frank.”

The tale was prompted by a slight disagreement between the famed photographer and I. Flipping through his latest book, In Color, which compiles some of his best chromatic photos, I was so awestruck by those taken in Wales 50 years ago that I wished for a separate opus entirely devoted to them. Davidson claimed that there was not enough material to warrant a volume that could compare to his acclaimed Brooklyn Gang, East of 100th Street, Circus or Subway. However, with a bit of coaxing, he had plenty to say about his time and affection for the Welsh coal fields, a fascination that could be traced all the way back to his childhood in Oak Park, Illinois.

“When I was a teenager, my mother took us to the Field Museum in Chicago where there was an exhibition on mining,” he says. “In it, they had recreated a shaft. When the door closed, the walls started moving faster and faster as if we were descending into the depth of the earth. That scared the shit out of me.”

More or less at the same time, the impressionable young Davidson discovered the magic of photography. After witnessing a print appear in what looked to him like “plain water” at a friend’s house, he excitedly ran home and begged his mom for a darkroom. They emptied his grandmother’s jelly closet – barely a meter wide – and transformed it into what became his haven. On the door, he wrote “Bruce’s Photo Shop”.

In the years that followed, he landed an internship with a local commercial photographer who showed him how to make dye-transfers, before studying at the Rochester Institute of Technology, where he tried to court a classmate infatuated with the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. “I thought that if I took pictures like him, maybe she’d fall in love with me too,” he explains of his early influences. Despite his best efforts, she favored the English teacher and he went on to serve in the Signal Corps as a photographer.

“I spent my first year in the Arizona desert before being dispatched to Paris in 1956. There, my sergeant was Welsh. One day, I asked him where he would send his worst enemy. He promptly answered: ‘That’s easy: Cwmcarn in Wales. It is such a terrible place’. And so, I took a three-day pass to see it for myself. Because of how long it took to get there and fearing that I’d be declared AWOL if I didn’t make it back on time, I spent less than an hour in the village. I didn’t take any pictures. I just stood there, taking in the sights of the coal dust and the flesh, of the sweat and the danger. There was something beautiful about a life that was so horrible.”

It’s easy to assume that similar sensibilities drove him, upon his return to America, to chronicle the lives of the disenfranchised, the outcasts. Moved by the transient nature of the traveling circuses, he befriended acrobats and followed them on-tour. He was especially fond of Jimmy Armstrong, a lonely dwarf working for the Clyde-Beatty troupe. The following year, in 1959, after reading an article about gang street fights in Brooklyn, he turned his lens on The Jokers, a restless group of teenagers. “It wasn’t about them being violent individuals, but about the violence of their neighborhood, of a society that had nothing for them,” he says.

This approach is symptomatic of Davidson’s work: he seeks to translate a mood, rather than illustrate a situation. He (re)creates a world for the viewer who cannot go where he has.

At the time, he lived in a one-room garret in the East Village. The kitchen doubled as the darkroom, and a red bulb replaced the fridge light so that he could eat and print at the same time. Tight quarters didn’t stop him from hosting the likes of Diane Arbus, André Kertesz, Richard Avedon, John Gossage or several of his colleagues at Magnum Photos. Davidson had joined the agency in 1958, after impressing Cartier-Bresson – the same man he once sought to imitate.

When fellow comrade and Welshman Philip Jones Griffiths heard of Davidson’s longing for the rugged terrain of his homeland, he readily introduced him to one of his compatriots, the bard Horace Jones. “He was unlike any other poet, he was really rough. He was a little crazy, and I think that’s why Philip chose him for me,” Davidson lets out with a snicker. Thanks to his uninhibited and knowledgeable companion, he was able to tour the region and meet with miners at work, at home and in bars. He captured their grim reality in black-and-white, as well as in color, thus proving his proficiency in both.

“Color has always been in my mind. I even think of black and white as colors, it just happen to be limited to two,” he explains, comparing himself to a baseball switch-hitter able to swing both ways depending on the score. “In Wales, I shifted to color because it was the best way to show the contrast of blackened powder on the skin, the only way I could render the acid chartreuse gas coming out of the factories against the dull skies.”

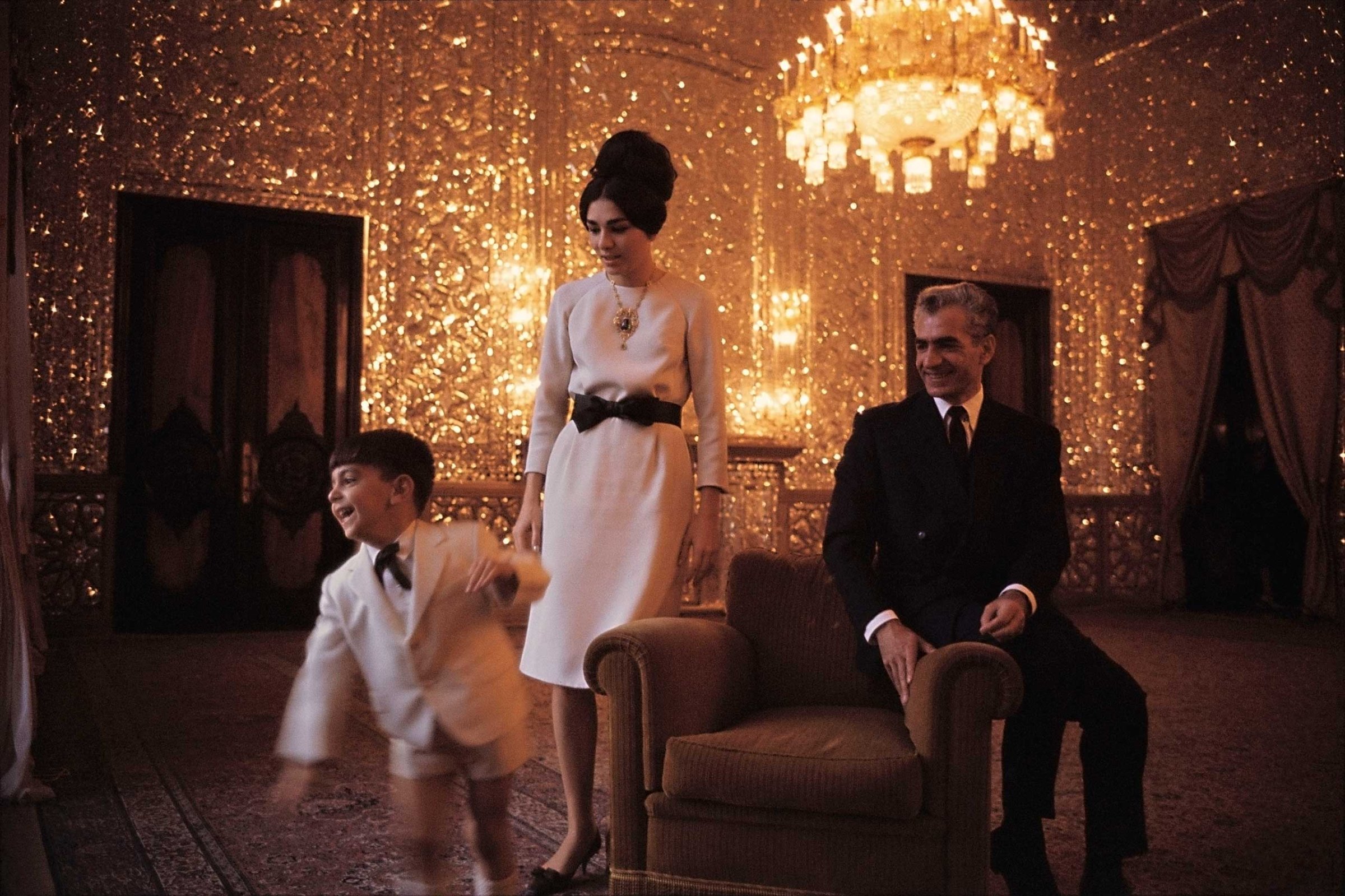

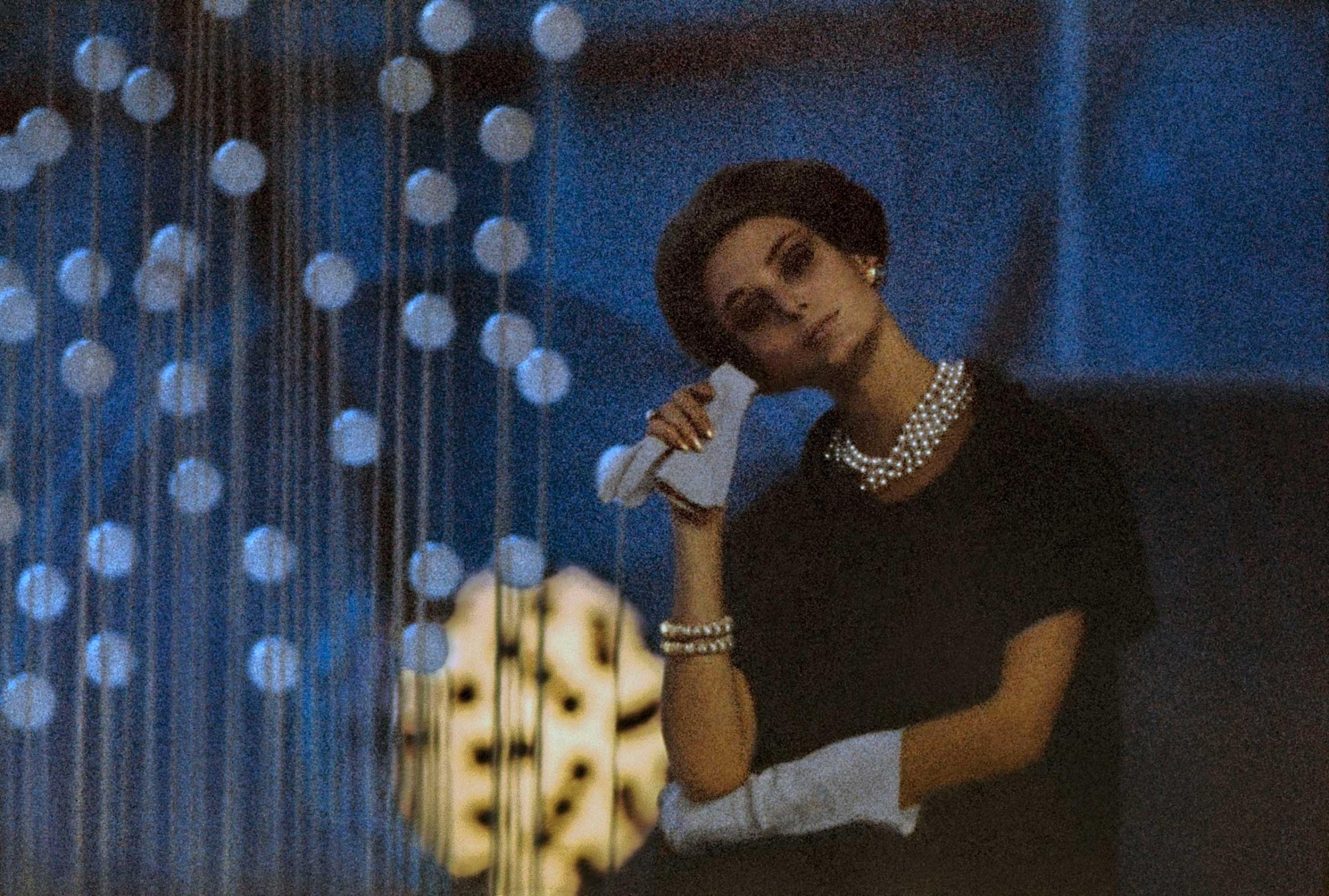

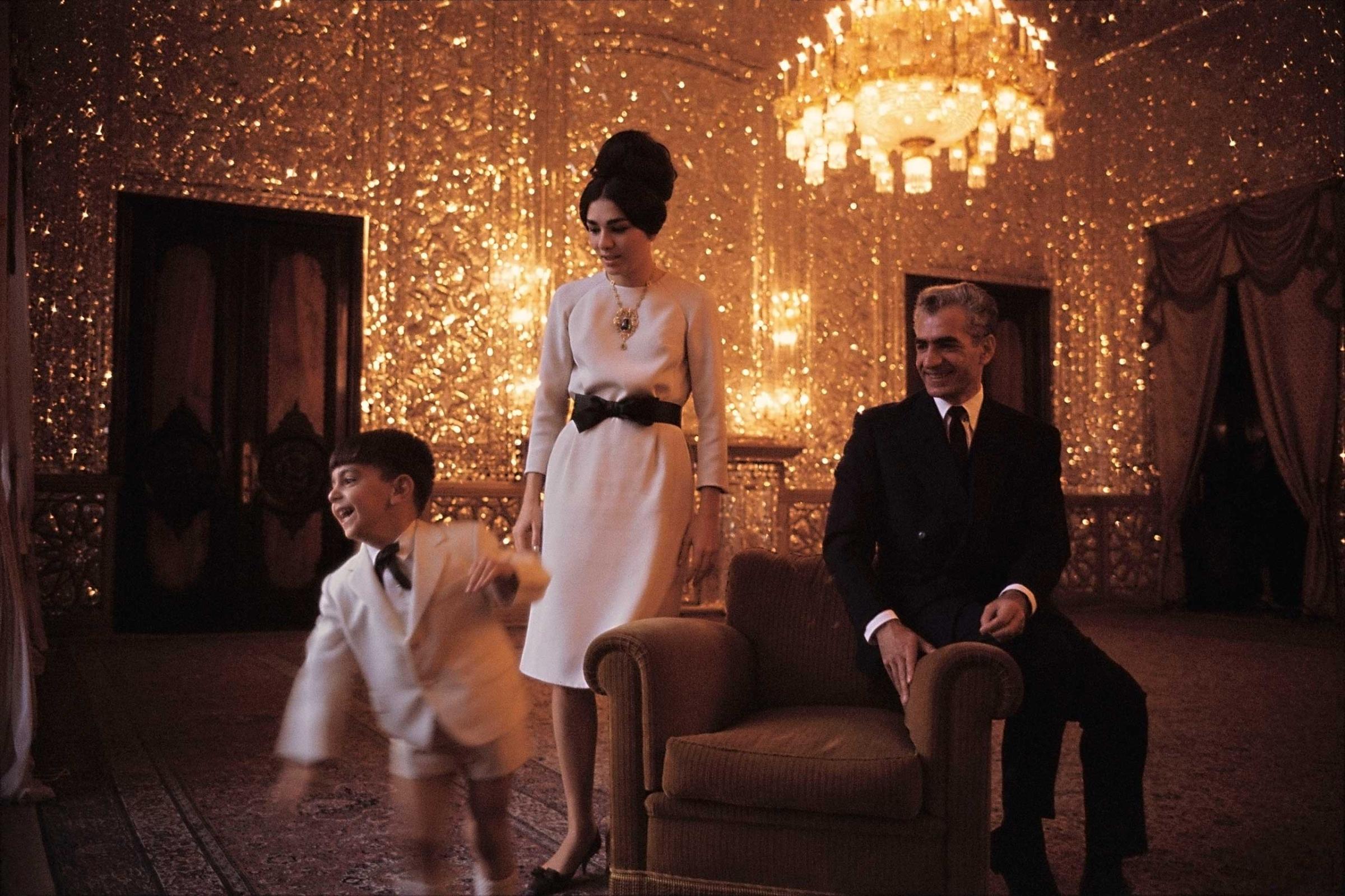

In Color makes clear that resorting to chromatic film was never an after-thought for Davidson, nor was it an exceptional one-off reserved to Subway, a series he produced in the 1980s. The book opens with photographs taken as early as 1957 and spans his entire career. It also brings to light the variety of styles he embraced, from anthropological studies à la National Geographic of faraway lands to romantic shots of his family’s vacations in Martha’s Vineyard, before closing with an outlandish look at Katz’s Delicatessen in New York City. “I just felt that no matter what, you have to make fun of Pastrami,” laughs the 81 year-old, who still aches to make new photos. As he said countless times before, and will repeat to anyone who asks, his favorite picture “is the one that comes next”.

Today, these are made with a digital camera, which gives him more leeway. “At my age, I can’t go running around through demonstrations. Not that I want to. I want to evolve into another realm of aesthetic reality,” he admits coyly. Nevertheless, he misses the delightful surprise of catching the first glimpse of an image in the ruby glow of the darkroom. He still has one, where he prays every morning and prints work from his archive when needed. It is in a nook pass the well-stocked kitchen. “I’m no longer allowed to eat in here,” he says with a wink. “Guess I’ve come a long way.”

Bruce Davidson is a photographer represented by Magnum Photos. His latest book, In Color, is published by Steidl.

Laurence Butet-Roch is a freelance writer, photo editor and photographer based in Toronto, Canada. She is a member of the Boreal Collective.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com