Food doesn’t have laws — like physics or math — but if it did, “everyone loves cookies” would surely be an indisputable truth. In fact, it’s along that line of thought that “Internet cookies” got their name, because they are all about sharing information — and cookies were made for sharing.

For example, imagine that a website asked your web browser if it would like a cookie. “I would love a cookie!,” it would likely respond, because that’s pretty much what you say whenever someone offers you a tasty treat. On a diet? Just hit the gym — it’s only a cookie, and you can burn it off whenever you want.

But now imagine another website saying, “Have a cookie.” These cookies are not optional, and even worse, you’re not able to throw them out, ever. That, essentially, is a “supercookie,” a web-tracking technology that privacy advocates want eliminated from the Internet.

Overall, cookies are intended to enhance and personalize your Internet experience, and sites from Amazon to Yahoo use them to tailor the web to your liking. “Traditionally when you’re using cookies on the web, it’s primarily for maintaining some site information,” says Satnam Narang, senior security response manager at Symantec. For instance, cookies can save your username on a website so you don’t have to type it in every time you go to log in. Advertisers also use cookies to take note of what products you search for, so they can serve relevant ads to you as you traverse the web. But you can also erase cookies through your browser settings, or turn them off so that they don’t get saved to begin with. Your web browser’s “private mode” is another great way to get around them, because cookies are not saved when this feature is enabled.

Supercookies, however, operate in a completely different way than standard web cookies. Instead of being a small file that gets saved by the web browser, a supercookie is a string of code injected into the data you’re downloading. Called a “unique identifier header,” this code cannot be deleted or wiped clean, because it is not a file.

“There’s no way for you to wipe that cookie away,” says Narang, “because it’s injected into your network traffic.”

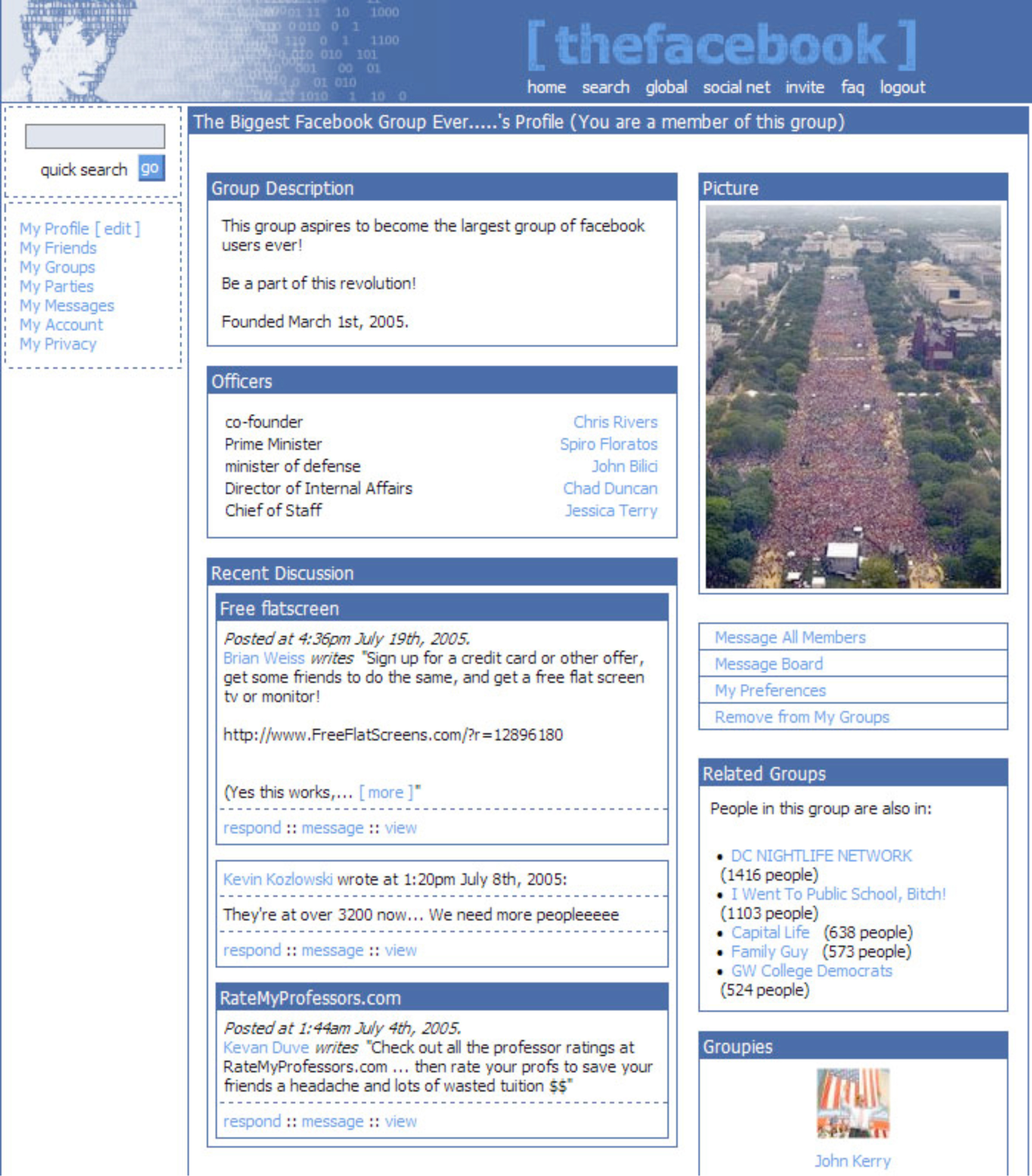

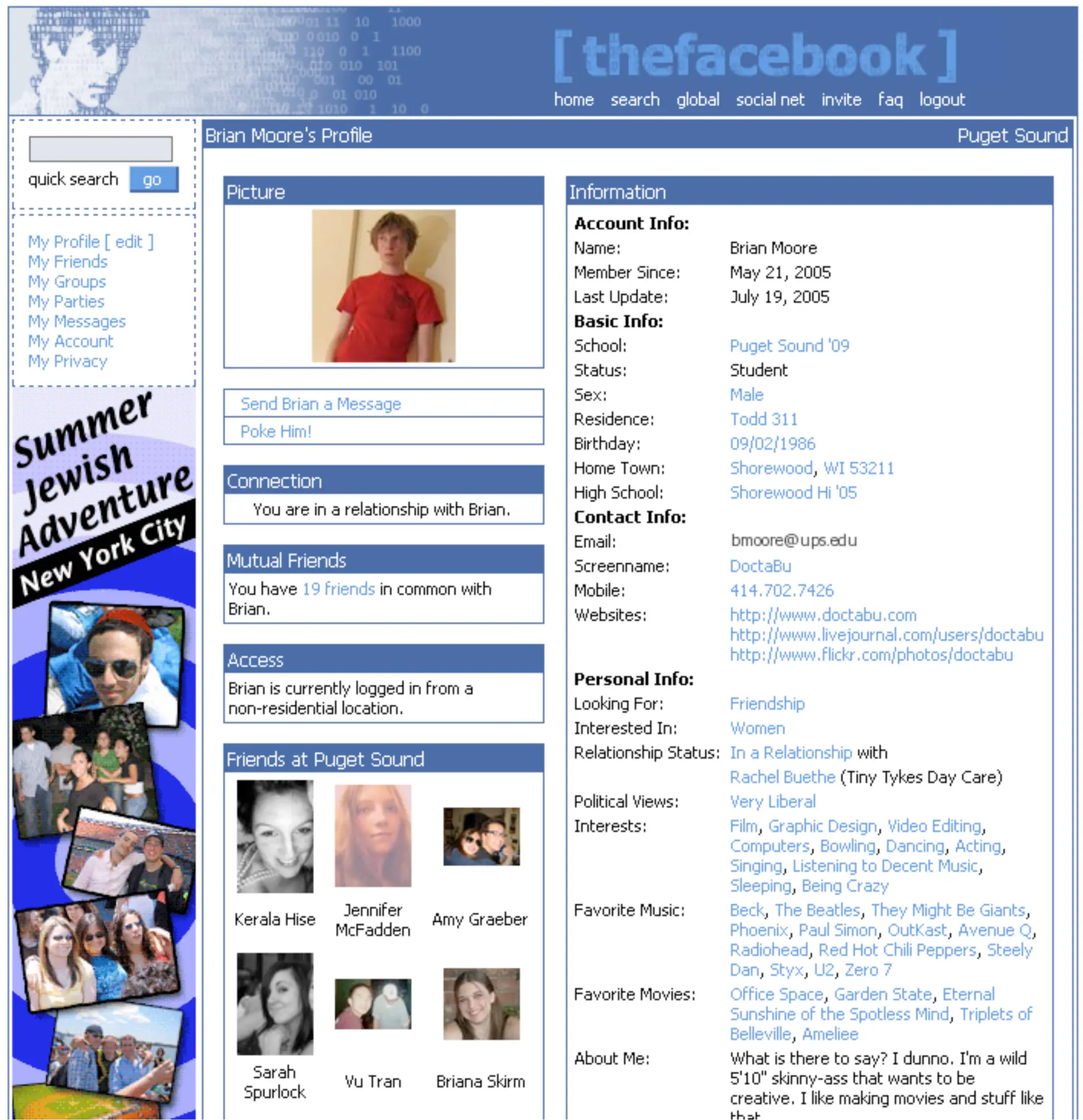

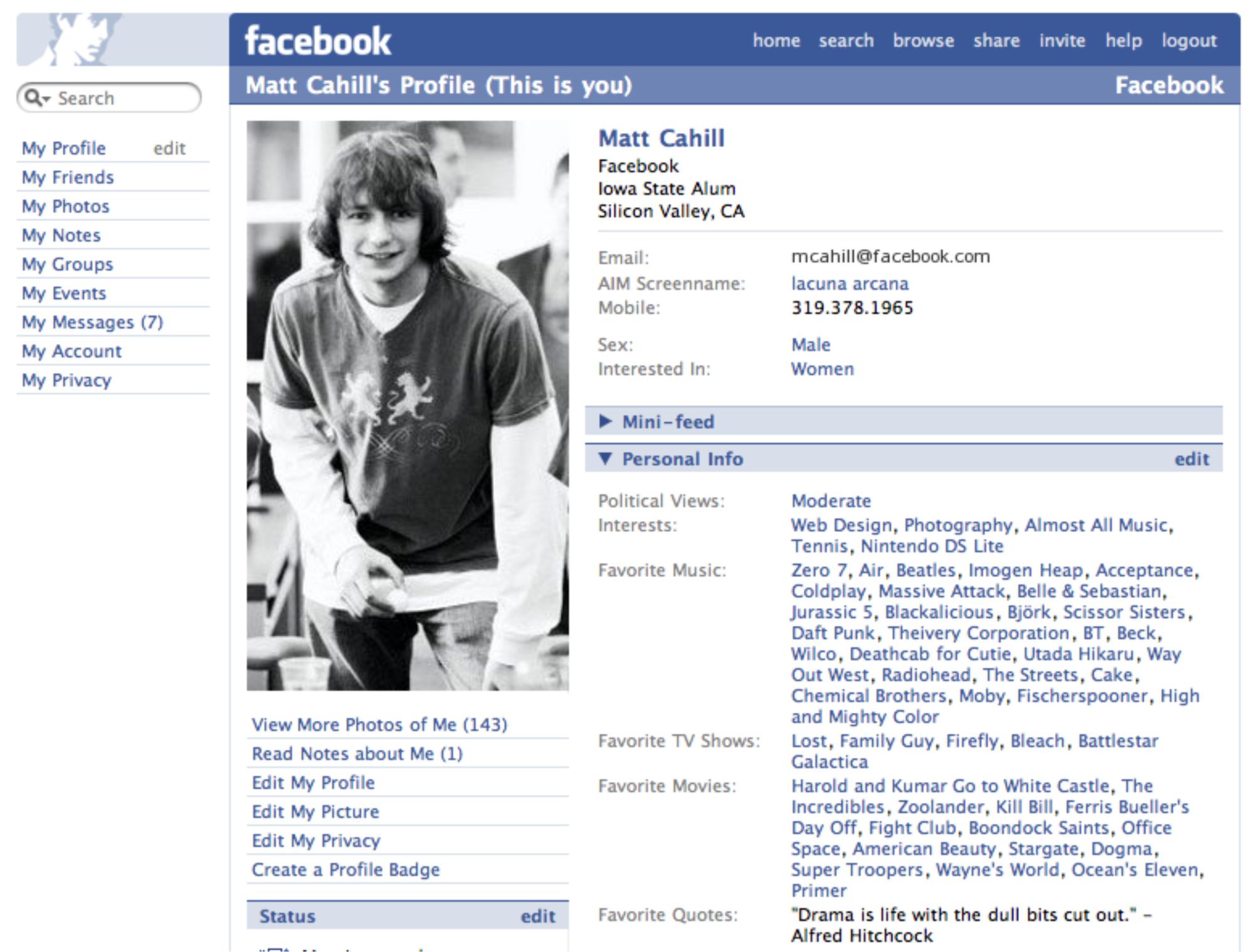

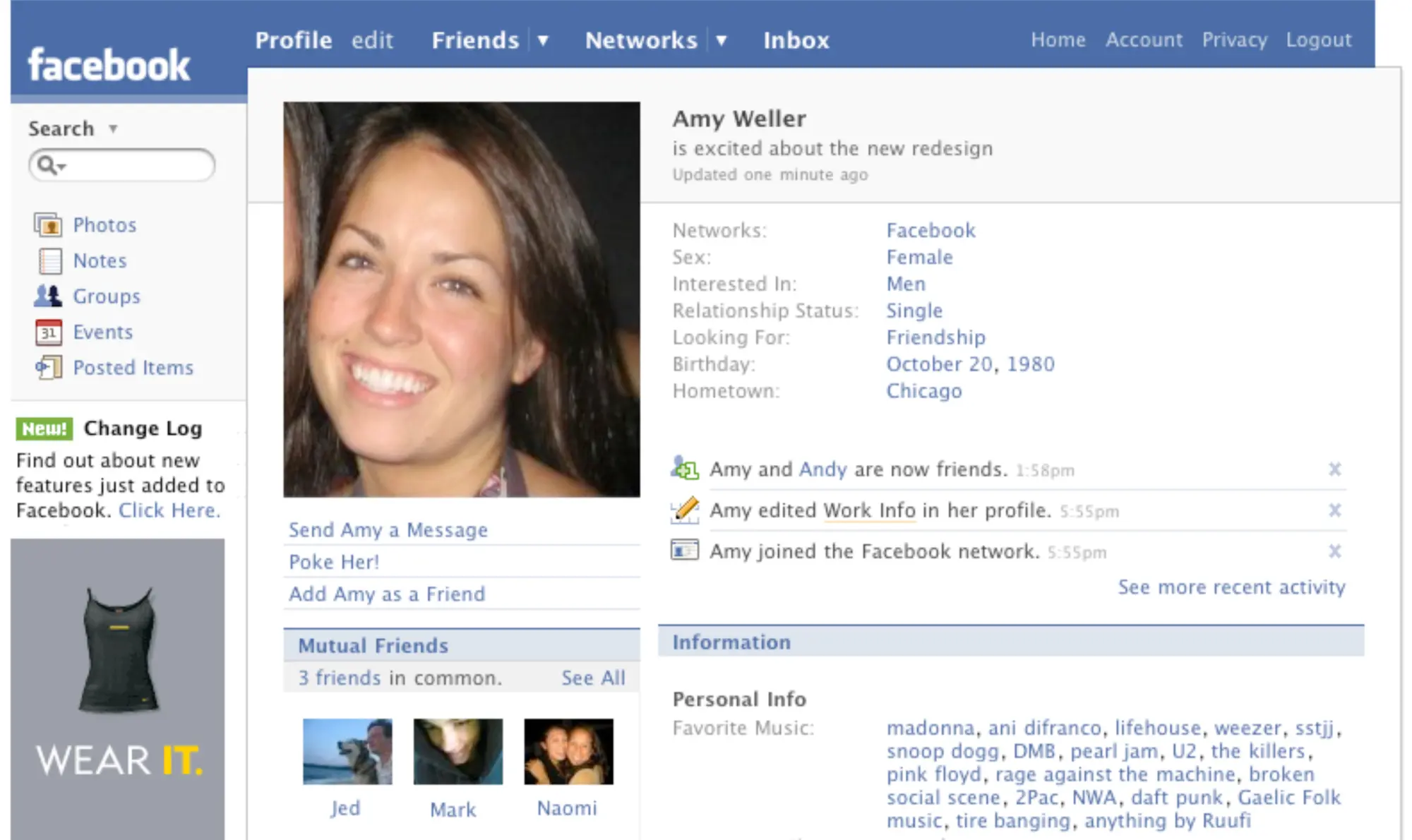

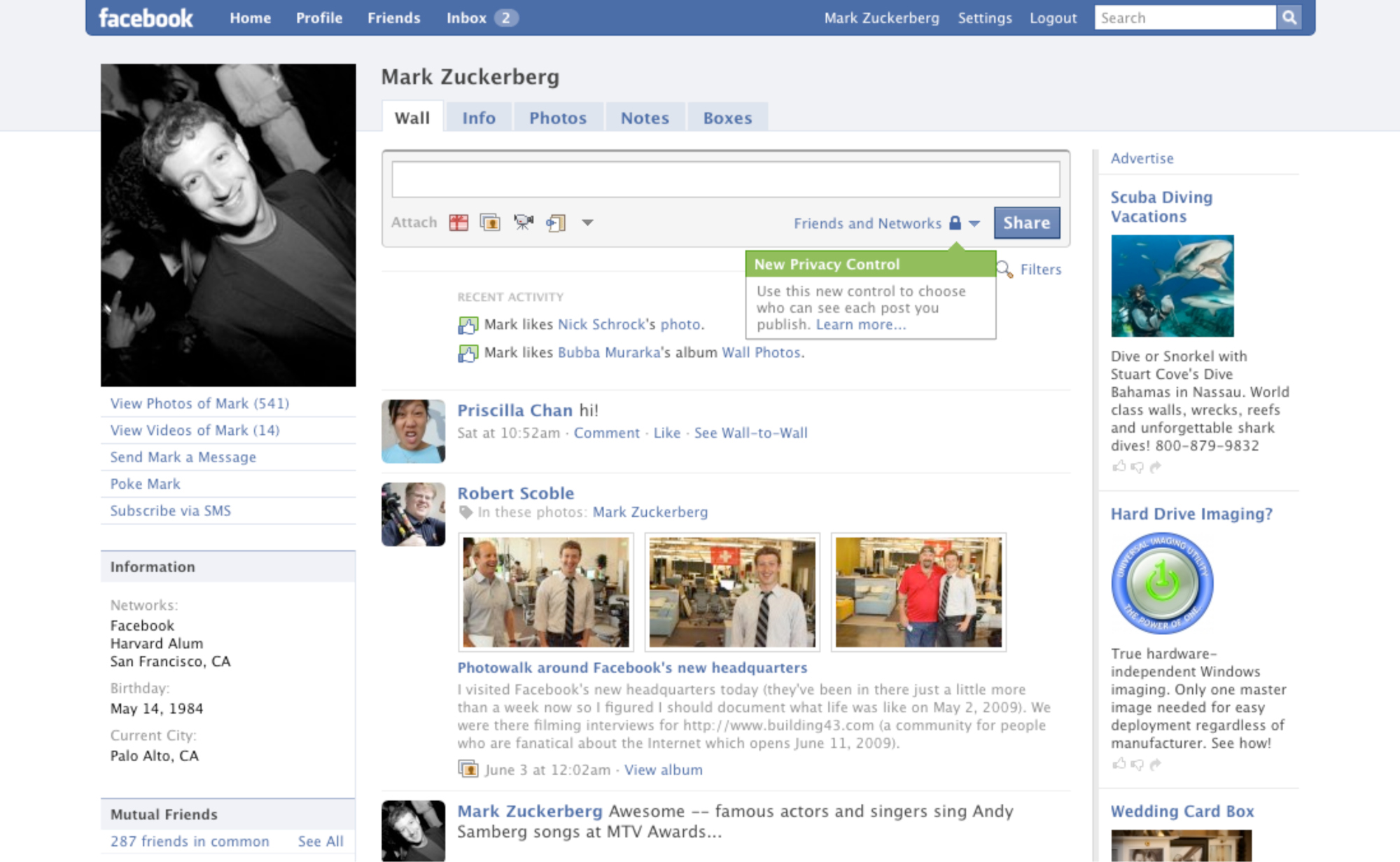

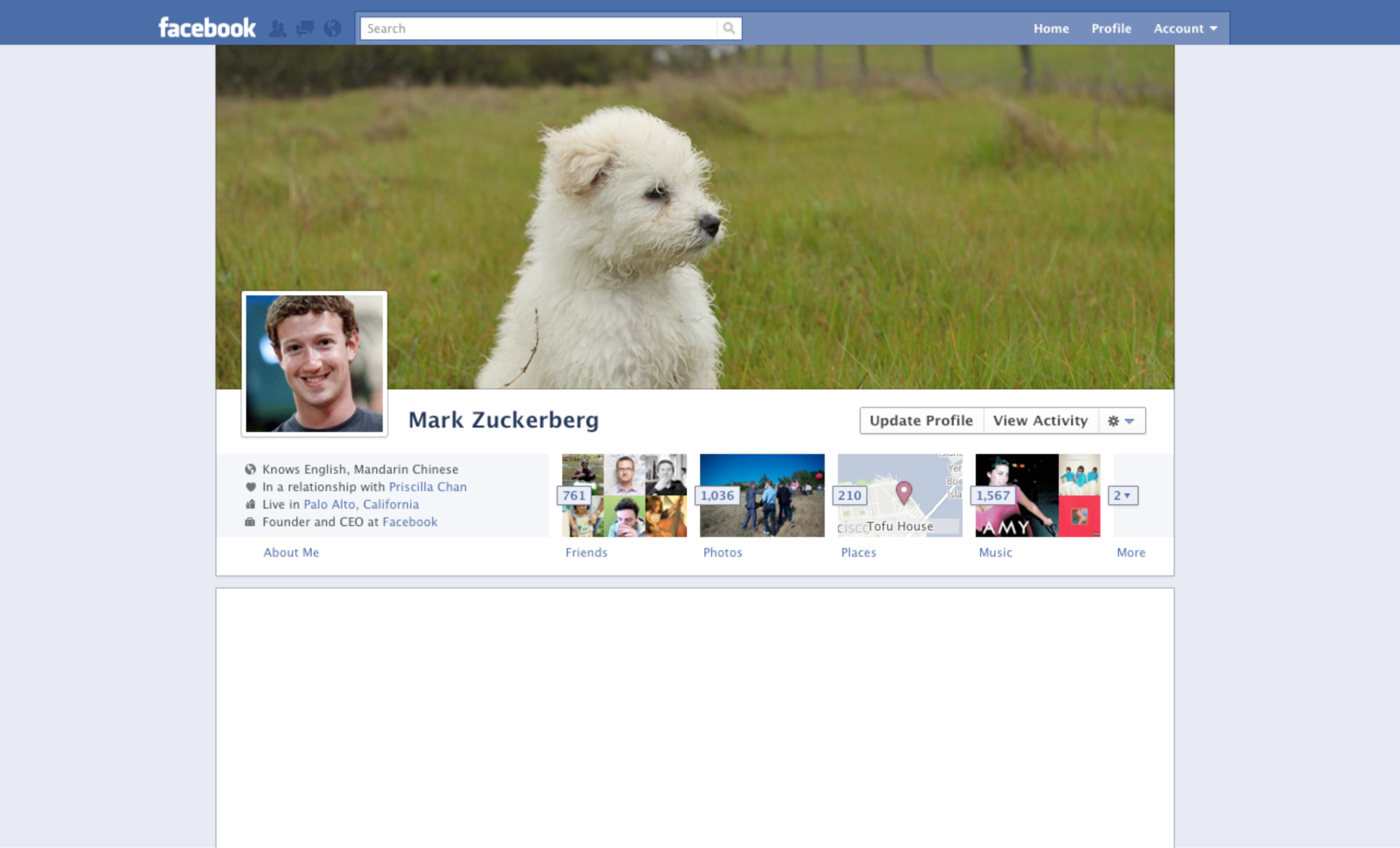

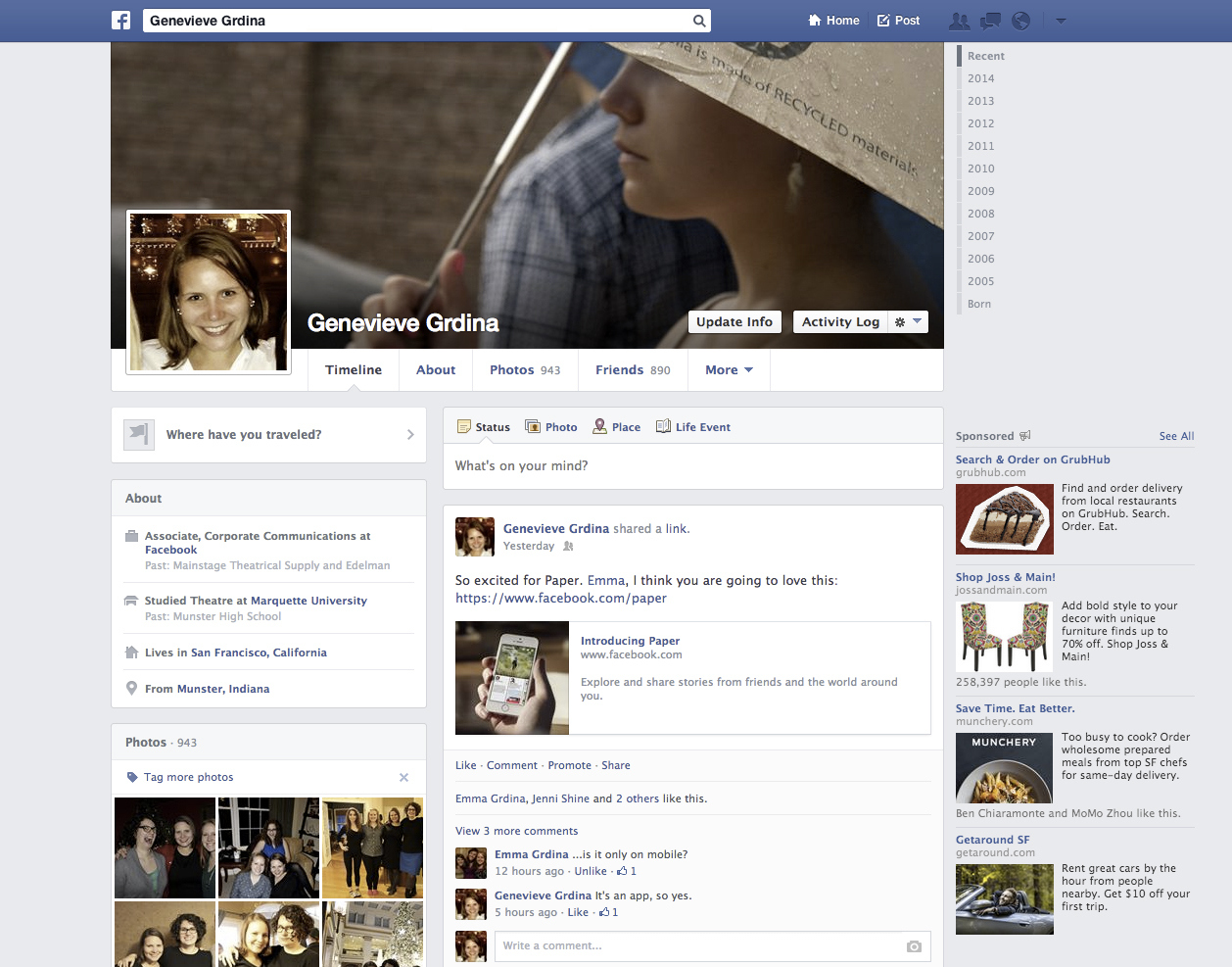

This Is What Your Facebook Profile Looked Like Over the Last 11 Years

Everyday web users wouldn’t know the difference between a cookie and a supercookie until they tried (and failed) to delete their browser-based cookies — and that is what has privacy advocates so alarmed. “Even if you wipe a cookie away, the fact that your ID header (or supercookie) still exists, they’re able to correlate those two separate instances of traffic,” says Narang. “They’ve already profiled not only the cookie, but that unique identifier header.”

Even if you’re browsing in private mode, websites can still monitor the websites you visited using supercookies. “The whole purpose of using private mode is because you want to just browse the website and not have anything saved,” says Narang. “You’re saying, ‘I don’t want you to save any information about me,’ and (with supercookies) that is not being respected.”

Supercookies were first revealed in 2011, when researchers at Stanford University and the University of California at Berkeley noted that sites like MSN and Hulu were using them. At the time, Congress began looking into the technology. In November 2014, The Washington Post revealed that Verizon and AT&T had been injecting supercookie code into their network traffic. AT&T stopped using the technology shortly thereafter, providing its subscribers with this opt-out link (click on the link with your AT&T smartphone, not your computer’s web browser). But it wasn’t until Monday — and more pressure from lawmakers — that Verizon agreed to let its subscribers opt-out of the online tracking. Its opt-out solution should be made available soon.

But keep in mind, however you have used these two mobile networks to access the web, whether it has been on a smartphone, through a tablet, or with a laptop connected to a hotspot, your online activities have been tracked, and will continue to be followed with supercookies until you opt out on each device. Talk about leaving a bad taste in your mouth.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com