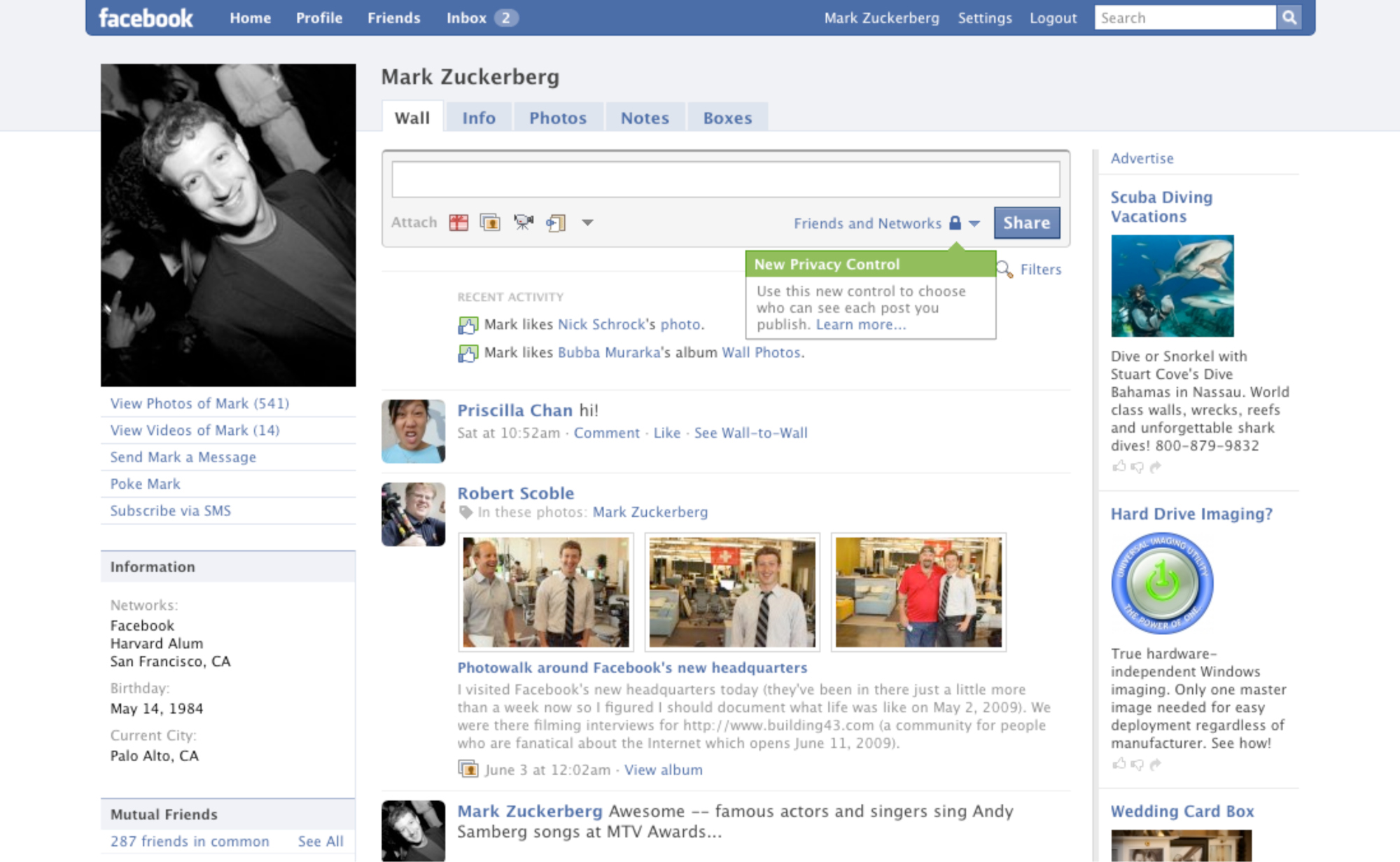

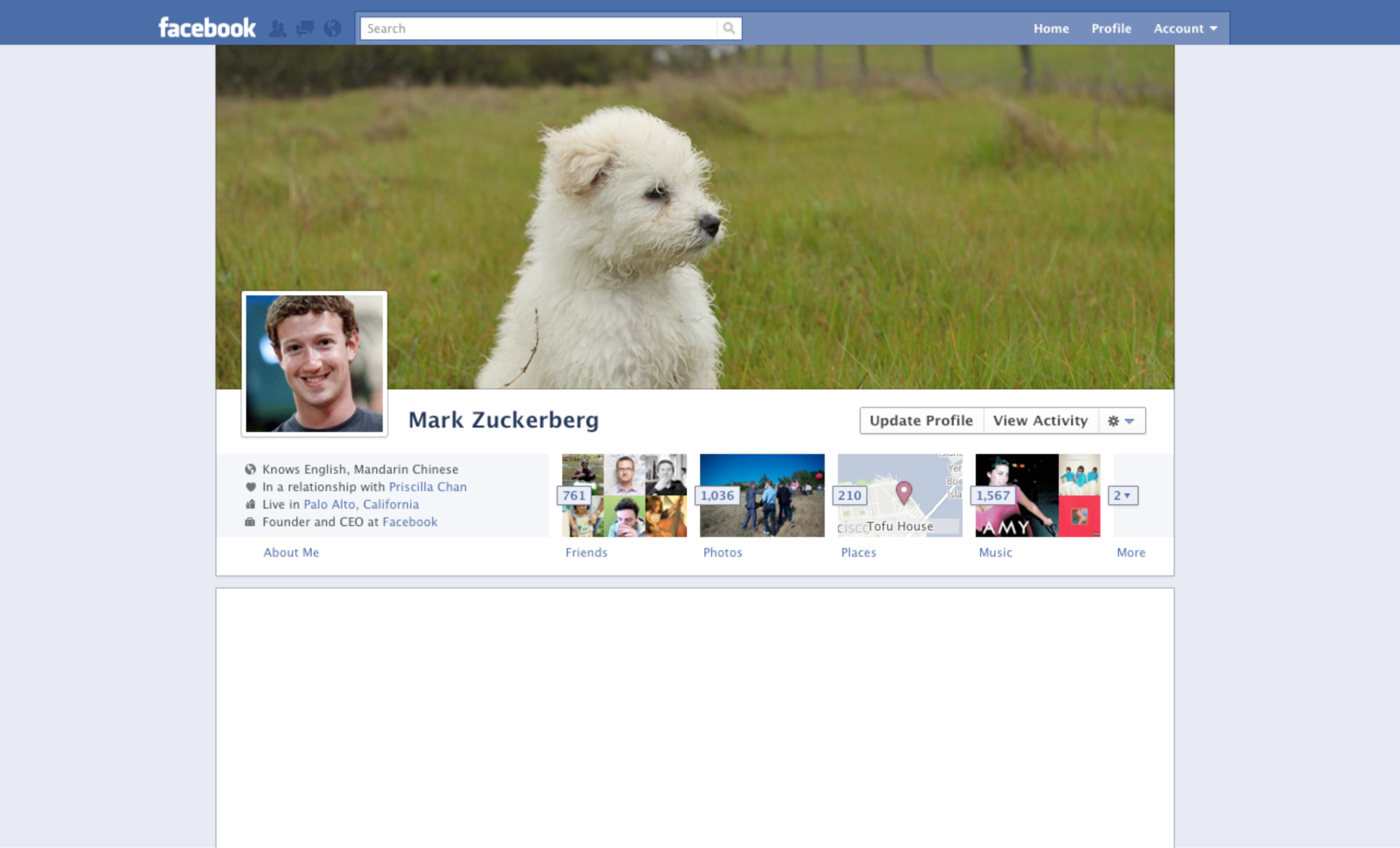

If you’re an early Facebook user like me, you remember when the site required that you had a college-supplied email address. For many users, those were the site’s glory days, a time when parents weren’t airing embarrassing throwback Thursday photos, people could post (nearly) anything they wanted, and there weren’t updates about the mundane nature of cubicle life.

This is the magic that new social network Yik Yak is trying to emulate, and so far, it has largely been a success.

A mobile, anonymous social network with apps for Android and iOS, Yik Yak launched in November 2013 and has been as hot as happy hour on college campuses ever since. “You can think of it as a local, anonymous Twitter or a local virtual bulletin board,” says co-founder Tyler Droll, who started the site with friend and fellow 2013 Furman University graduate Brooks Buffington.

On Yik Yak, users make text posts, also called “yaks,” that can be up- or down-voted by other “yakkers.” These votes help rank each yak: the higher the score, the more popular the post. Yaks can also be commented on, turning the posts into conversation threads. Every post or comment on the network is anonymous — users don’t even get a photo or avatar to distinguish themselves.

Buffington and Droll originally launched the network on their alma mater’s Greenville, South Carolina campus before it quickly spread to other schools. “People started sharing it at various spring break locations,” says Droll of the network’s 2014 surge. “We probably ended the spring semester at around 200 or 300 campuses.” Over the following summer, Yik Yak got even more popular, with college students heading home and telling all their high school friends about it. At one point in the fall, says Buffington, Yik Yak was effectively tied with Facebook for the amount of downloads.

Today Yik Yak is available on around 1,500 college campuses. “We’re starting to get a pretty good foothold into other English-speaking countries like Canada, the U.K. and Australia,” says Buffington.

This Is What Your Facebook Profile Looked Like Over the Last 11 Years

The bathroom wall

One problem for the service is that it’s being used where it’s not supposed to be — namely, at high schools. “I hate Yik Yak, but I can’t quit Yik Yak,” bemoans my 16-year-old niece. The site’s trash-talking nature is what she dislikes most, but she says she can’t quit it because she feels like she’ll be missing out on conversations her friends and classmates are having. In that way, Yaks can also be like a nasty note scrawled on the bathroom wall. One person wrote it, some people are talking about it, but everyone saw it.

Anonymous social networks can be especially perilous for younger users, because they can be a hive of cyberbullying, racist barbs and hate speech. For instance, in an online petition signed by more than 78,000 people calling for the app to be shut down, one former Yik Yak user outlined how she was encouraged to commit suicide by other anonymous people using the app.

Yik Yak has made efforts to keep younger users off the site by geofencing off grade school campuses in each country it operates, effectively blocking the service from being used in those locations. But once kids leave school grounds, they’re able to open the app — and that’s where parents need to step in and help their children make safe choices on the Internet.

“We try to keep anyone who’s not college age or older off the app, just because the way our app is set up it requires a certain level of maturity,” says Buffington. “Right now I’d say at least 95%, if not more, of our users are college-age kids.”

And while Yik Yak is artificially tethered to college campuses, the app gives anyone the ability to peek at the local buzz, especially if they use it in a dense, urban area where several colleges overlap. Or to check out what the conversation is on a particular campus, Yik Yak’s “peek” feature lets users browse yaks at schools worldwide. It’s a great way to reconnect with your old college. For instance, I wasn’t surprised to see Syracuse University students are still complaining about the epic staircase leading to the dorms on “The Mount.” Or you can use it to see the unfiltered reaction to news emanating from campuses worldwide. For example, someone from Dartmouth College recently posted, “If your [sic] going to ban hard liquor, have the decency to put a Chipotle in town.”

While a great many of its posts are about sex, booze, and syllabi, Yik Yak can also be a great tool for those looking to connect to their community, whether that’s through getting support for LGBTQ issues (yaks about coming out are generally met with encouragement, and the few disparaging comments are generally attacked themselves) or even addressing safety concerns.

“We’ve seen campus alert systems brake, and they used Yik Yak to get the word out about snow days and iced roads,” says Droll, who also points out that Florida State used Yik Yak to alert students of a recent shooting situation.

But don’t expect Yik Yak to stay in school forever. Though Huffington and Droll declined to provide details, they said they plan to take it off campus in the future.

“We’ve seen it work really well at airports and Disney World and just anywhere in the world there’s a collection of people,” says Droll. “Right now we’re focused on colleges and starting there much like Facebook did.”

So, mom and dad, when the time comes, please yak responsibly.

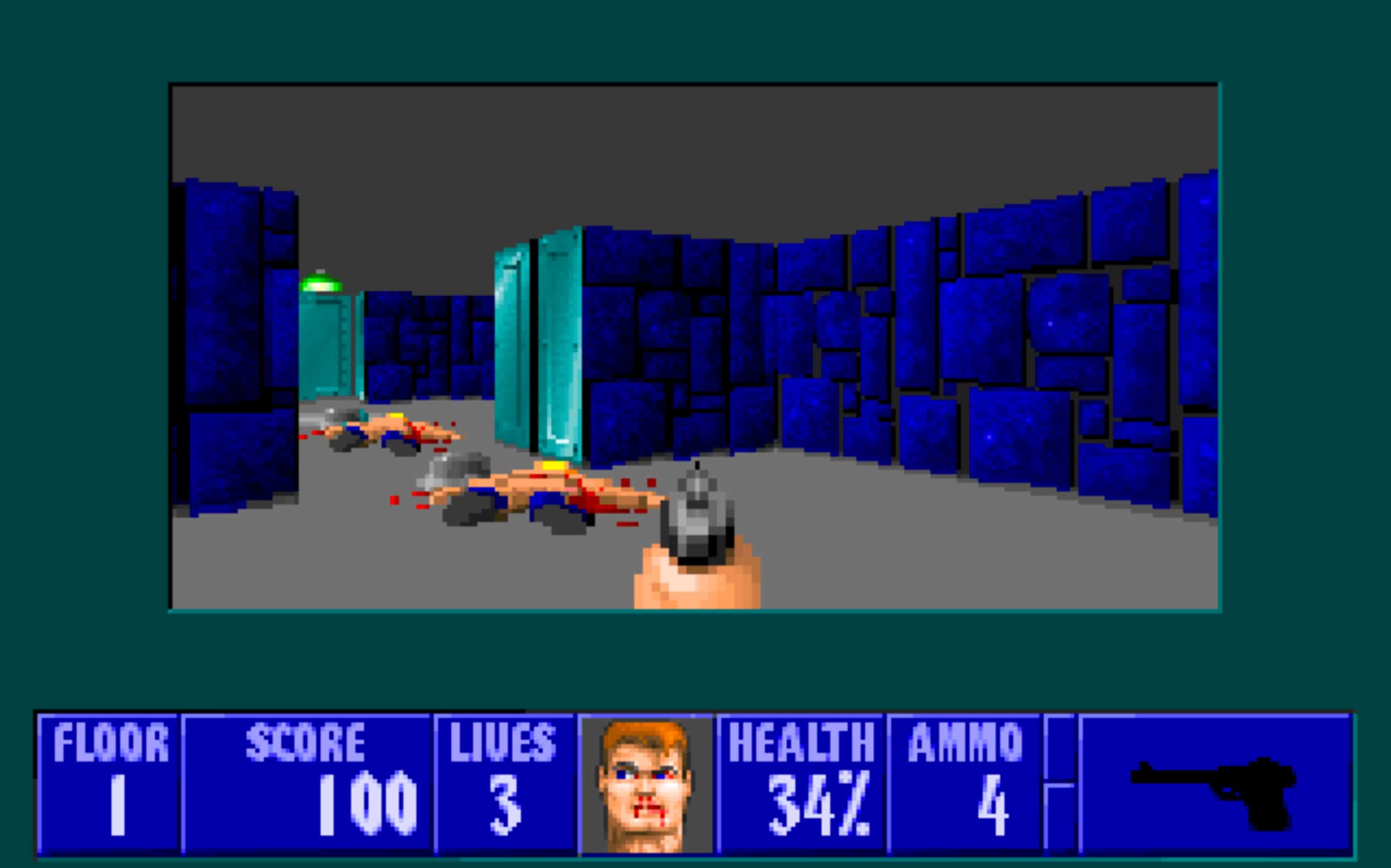

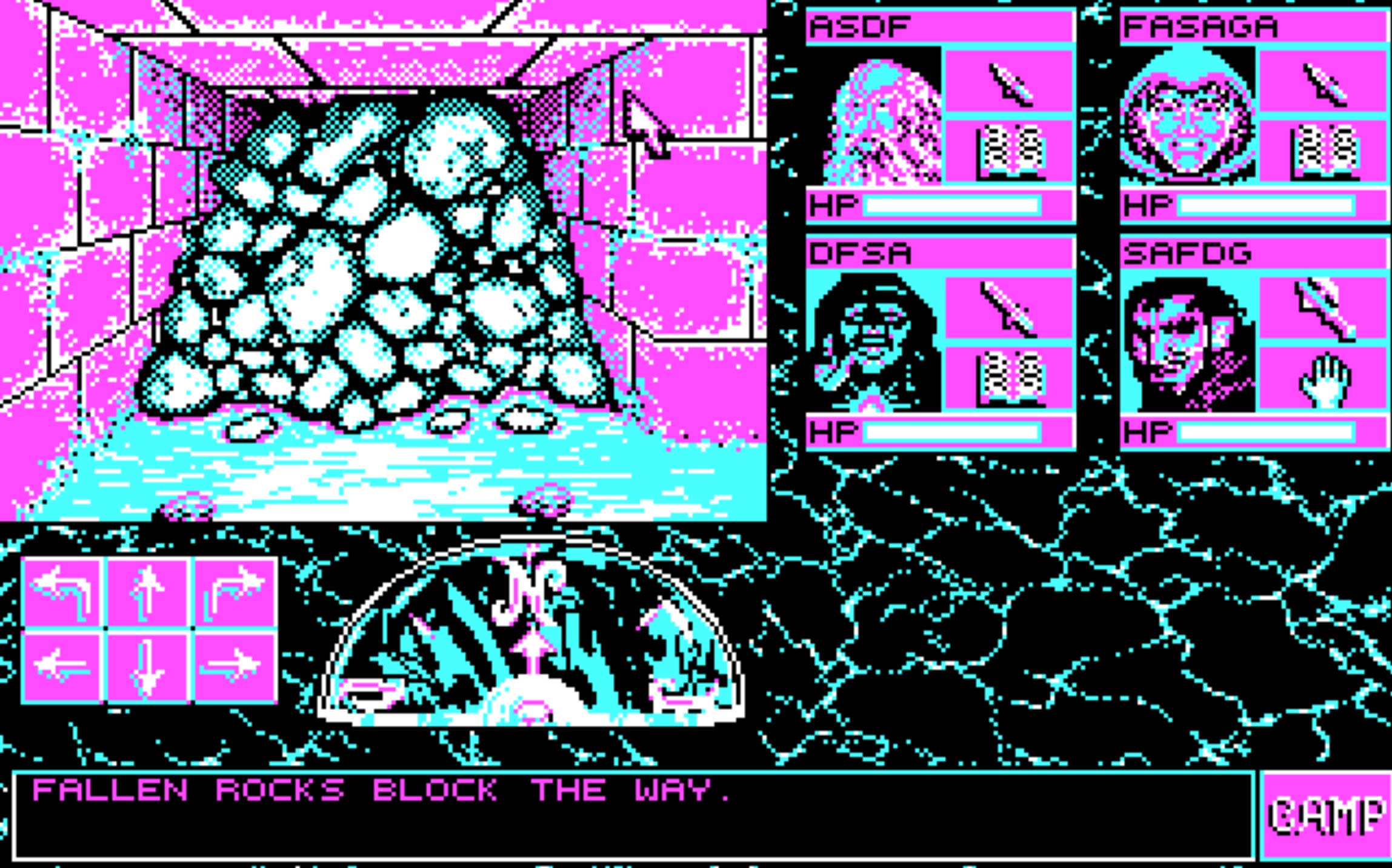

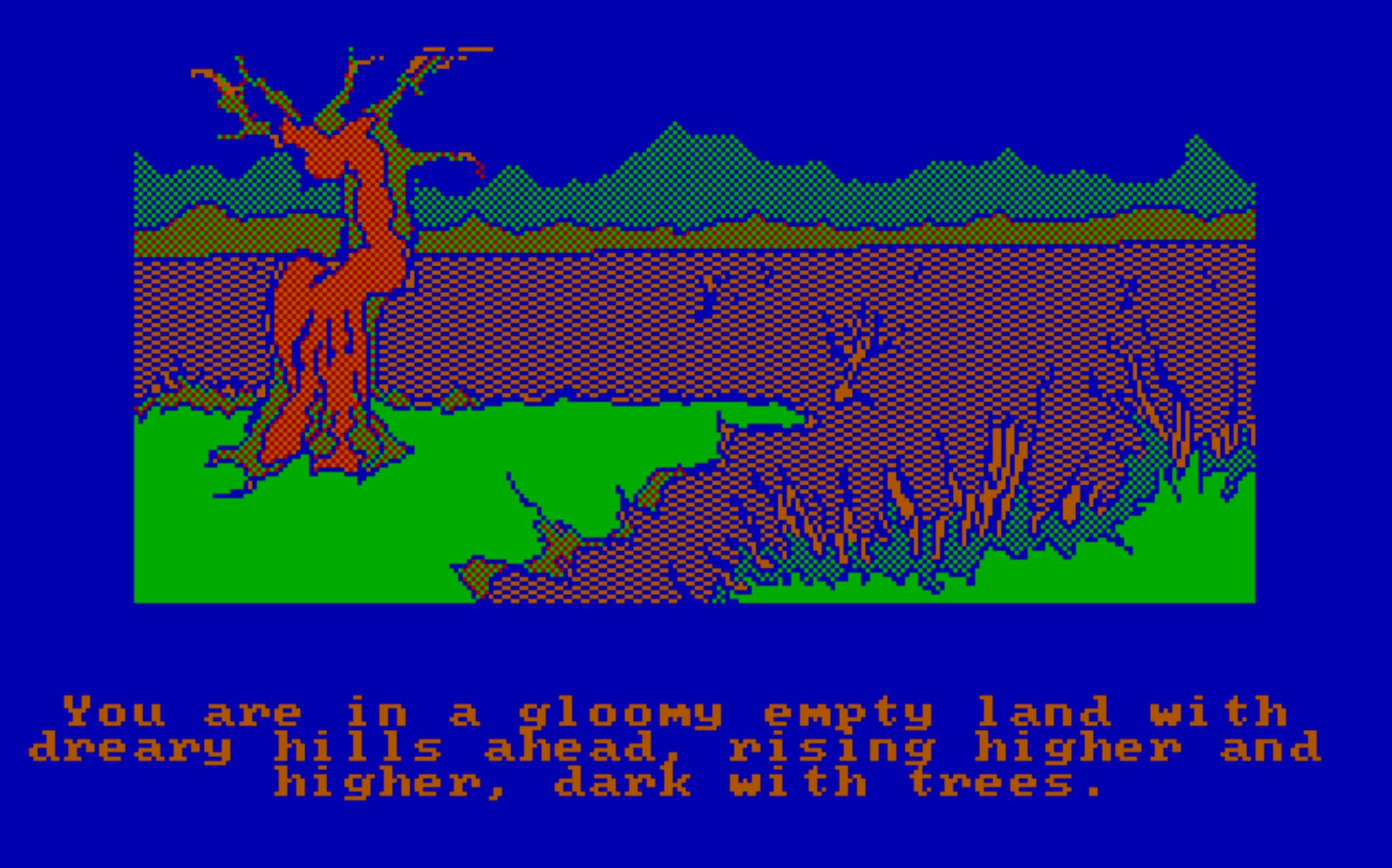

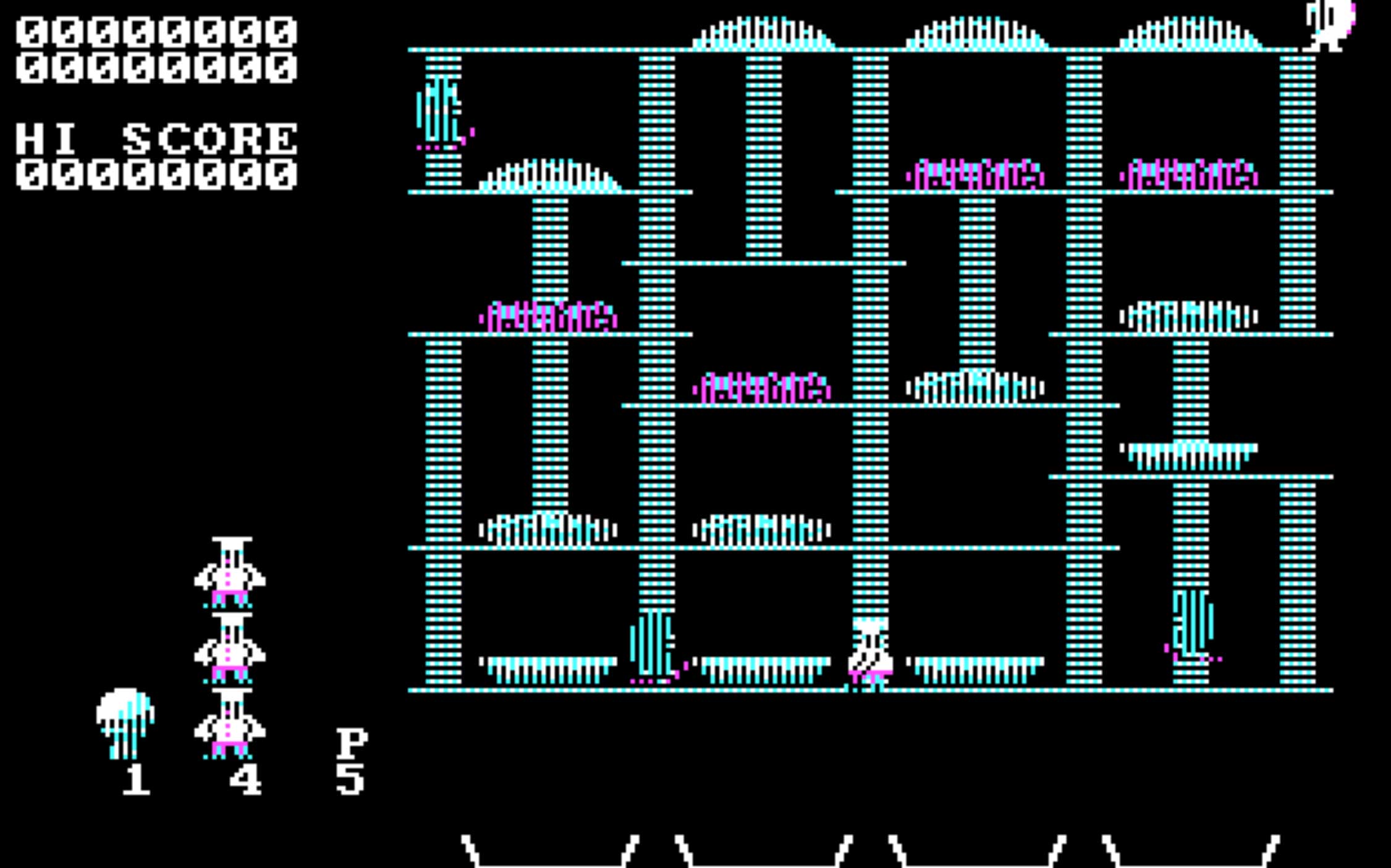

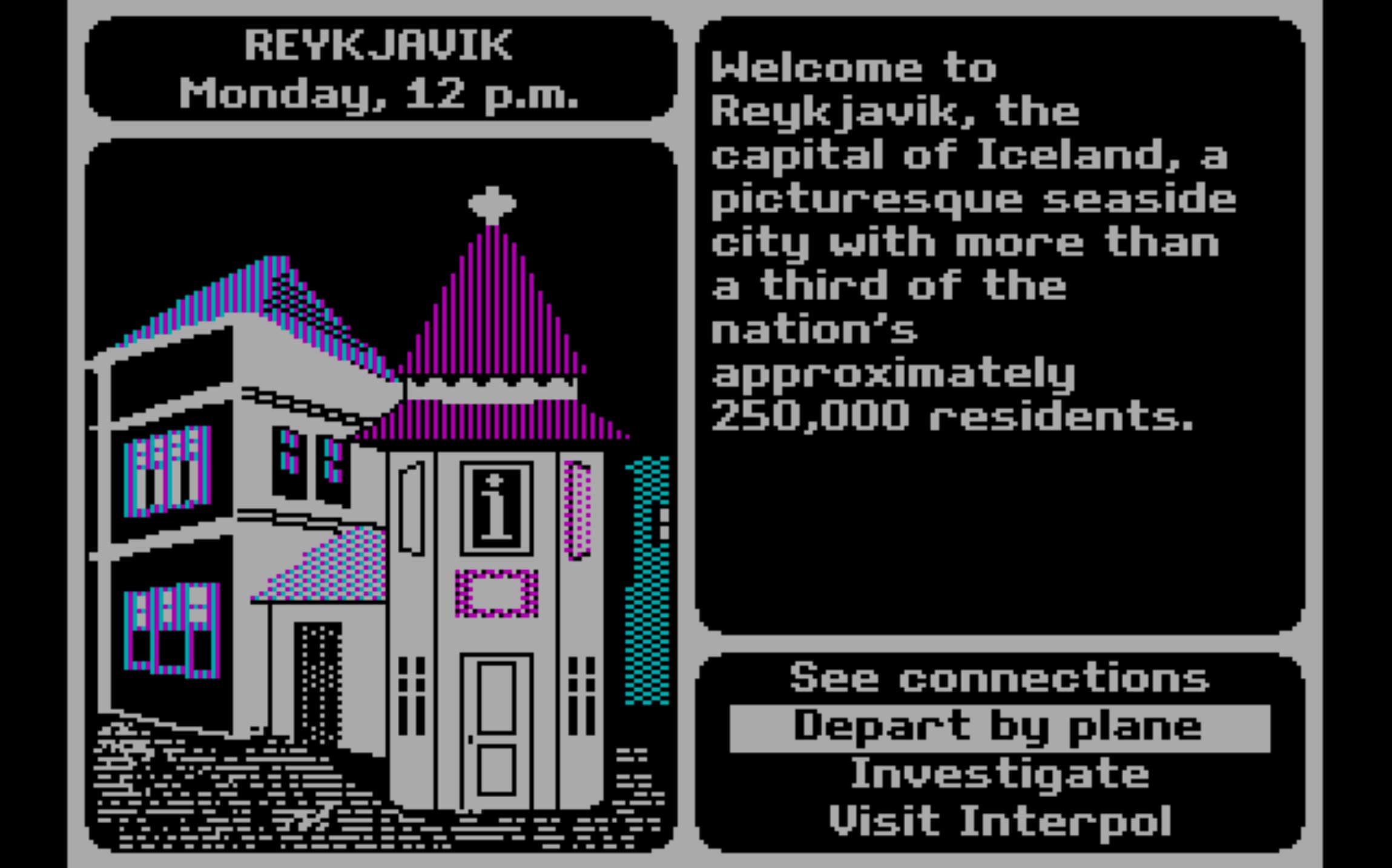

The 10 Best Classic PC Games You Can Play Right Now

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com