We live in the age of artistic authenticity, or at least of arguing about it. Was Selma true to LBJ? Was American Sniper true to the Iraq War? Was The Imitation Game true to Alan Turing’s experience as a gay man?

Now we have ABC’s Fresh Off the Boat, based on a memoir by chef Eddie Huang, who has said the sitcom strays from his true experience, though he produces the show and ultimately gave it his conflicted endorsement. (Huang himself is known for challenging assumptions about cultural “authenticity” through his work; he founded Baohaus, a New York City restaurant whose menu has included traditional Taiwanese pork buns and Cheeto fried chicken.)

I don’t know how authentically Fresh represents Huang’s childhood. (Huang himself wrote a long, nuanced essay on the experience for New York magazine, and you should read it.) I don’t know if it authentically represents the Asian-American experience, more specifically the Chinese-American experience, more specifically the Taiwanese-American experience. I don’t know how authentically it represents the experience of being an immigrant’s child. (Well, a little—my mom came to small-town Michigan from Morocco in her 20s—but only very little.)

But one thing I do know is that Huang’s story itself is largely about questioning the idea that there is a single “authentic” form of any experience. In Fresh, we meet 11-year-old Eddie (Hudson Yang) as his family’s moving from Washington, D.C.’s Chinatown to Orlando in 1995. He doesn’t fit in with his mostly white new classmates, yes, but he also doesn’t fit with either society’s or his parents’ expectations of what a young Asian-American kid should be. For one thing, he’s in love with rap music for its swagger and defiance: like Notorious B.I.G., he tells us in voice-over, he’s “just trying to get a little bit of respect in the game.”

Another thing I know: Fresh Off the Boat (premieres Feb. 4) is damn funny—but not only funny and not cheaply funny. Three episodes in, it’s the best broadcast comedy of the new season, a daring but good-hearted sitcom about the complexities of identity—about not only being different but also being different from the different.

Fresh immediately establishes a sense of place and stakes. The Huangs are taking a risk, moving to sunny, white Florida so that father Louis (Randall Park) can open a tchotchke-filled Western-style steakhouse (Cattleman’s Ranch, which everyone but Louis mistakes for a Golden Corral). Louis is relentlessly optimistic; mom Jessica (Constance Wu) is dubious and alienated among the rollerblading housewives and suburban American supermarkets. (“What is this store so excited about?” she wonders on a shopping trip.)

The Huang kids are more adaptable—well, two out of three are. Eddie briefly bonds with his new white classmates (over their love of Biggie) then is quickly shunned when he opens his lunch of pungent Chinese noodles. But his roughest conflict in the pilot comes with a black classmate, who doesn’t like being Eddie’s Friendship Plan B—”Oh, it didn’t go well? The white people didn’t welcome you with open arms?’’—and turns on him nastily: “You’re the one at the bottom now. It’s my turn, chink!”

It’s a stunning climax in a mostly light half-hour, and it feels like a mission statement. This is not going to be a show in which the stars “just happen to be Asian,” because it takes place in our world—20 years ago, but the world nonetheless—where nobody “just happens” to be anything.

Impeccable casting goes a long way toward pulling this off. Yang has immediate presence as Eddie, putting on a stoic, defensive scowl and wearing his Nas T-shirt like a coat of chain mail. But while this is very much Eddie’s show, the adults nearly steal it, particularly Wu, who gives a breakout performance.

Demanding, acerbic, ranging from passive-aggressive to aggressive-aggressive, Jessica would be an easy character to play as a simple “Tiger Mom” (a concept the voice-over references). But the comically agile Wu puts such spin on her line readings that she conveys much more about the character—her sense of humor, her vulnerability, her protectiveness. As Louis, Park is a counterpoint, but he’s more than the nice guy: they represent two sides of outsider life, assimilation vs. tradition, optimism vs. defensiveness, trust vs. guardedness.

Like the recent ABC comedies blackish and Cristela, Fresh shakes up the family-comedy format by focusing on a family of color, and it uses the specifics of the Huang family’s background to create a sense of place and point of view. But it also has something in common with recent ABC sitcoms like Suburgatory and even alien comedy The Neighbors—it’s an outsider comedy that gives us a new perspective on the majority. In the second episode, for instance, the NASCAR-obsessed neighbors try to explain the appeal of auto racing during a Daytona 500 party, and their mainstream culture ends up sounding as weird and alien as anything. This may be a fish-out-of-water story, but the joke is, mostly, on the water.

Producer Nahnatchka Khan (Don’t Trust the Bitch in Apt. 23) reportedly wrangled with Huang over the adaptation, but the result is a show with more voice after three episodes than most sitcoms have after three years. In the way of TV series like Freaks and Geeks, Fresh uses pop culture not just for reference humor or easy nostalgia but as a tool to develop character; Eddie’s attachment to O.G. ’90s rappers is not just a sight gag, it’s the way he projects a sense of self. The show has ideas, and it has a take.

It also has the burden of representation. Because there are so few series with Asian regulars—it’s the first Asian-American family sitcom since All-American Girl two decades[!] ago—Fresh is inevitably going to be scanned for stereotypes and generalizations. Seen through that frame, Jessica does sometimes evoke tiger-mom stereotypes, and Louis does recall pop-culture images of the nice, unthreatening Asian man. But they also recall a tradition of good-cop-bad-cop sitcom parents–say, Malcolm in the Middle‘s Lois and Hal–and at the same time, they feel like distinct, realized individuals.

(See, for instance, when Louis decides that he needs to hire a white greeter, played by Paul Scheer, to drum up business at Cattleman’s Ranch: the customers, he says, need to see a face that makes them say, “Oh, hello, white friend! I am comfortable! Nice, happy white face like Bill Pullman!” Is he accommodating? Does he want to be liked and accepted? Yes–but he’s also entirely aware and canny about how he’s being accommodating. He’s a small-businessman whose job is to solve problems–one of which is being a Taiwanese man selling cowboy food to white Floridians.)

That there aren’t more Asian, especially East Asian, stars on American TV is a problem–and, historically, an embarrassment. But it shouldn’t rope Fresh, a show that’s trying to tell a story about the messiness of multiculturalism, into responsible dullness. It’s to the credit of Khan, Huang and the rest of the team that–so far–it hasn’t.

I doubt any network sitcom is going to prove very true to Eddie Huang’s life, or any real person’s. But in a way, that may be fitting for a show whose themes are about combining authenticity with artifice–about how you get to Baohaus by way of Cattleman’s Ranch. “True” or not, Fresh Off the Boat could prove to be distinctive, funny and lasting–and yes, even important–if it stays true to itself.

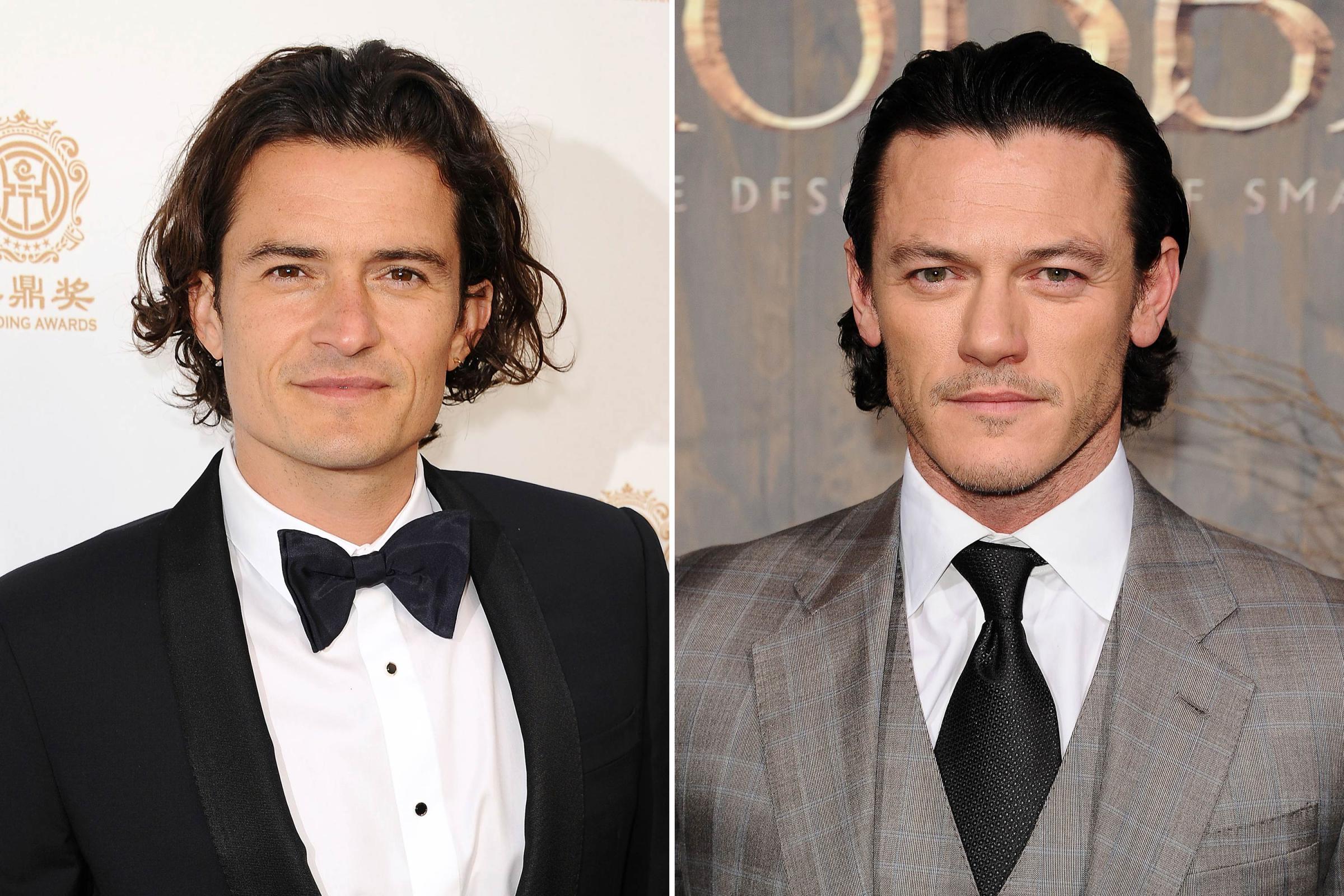

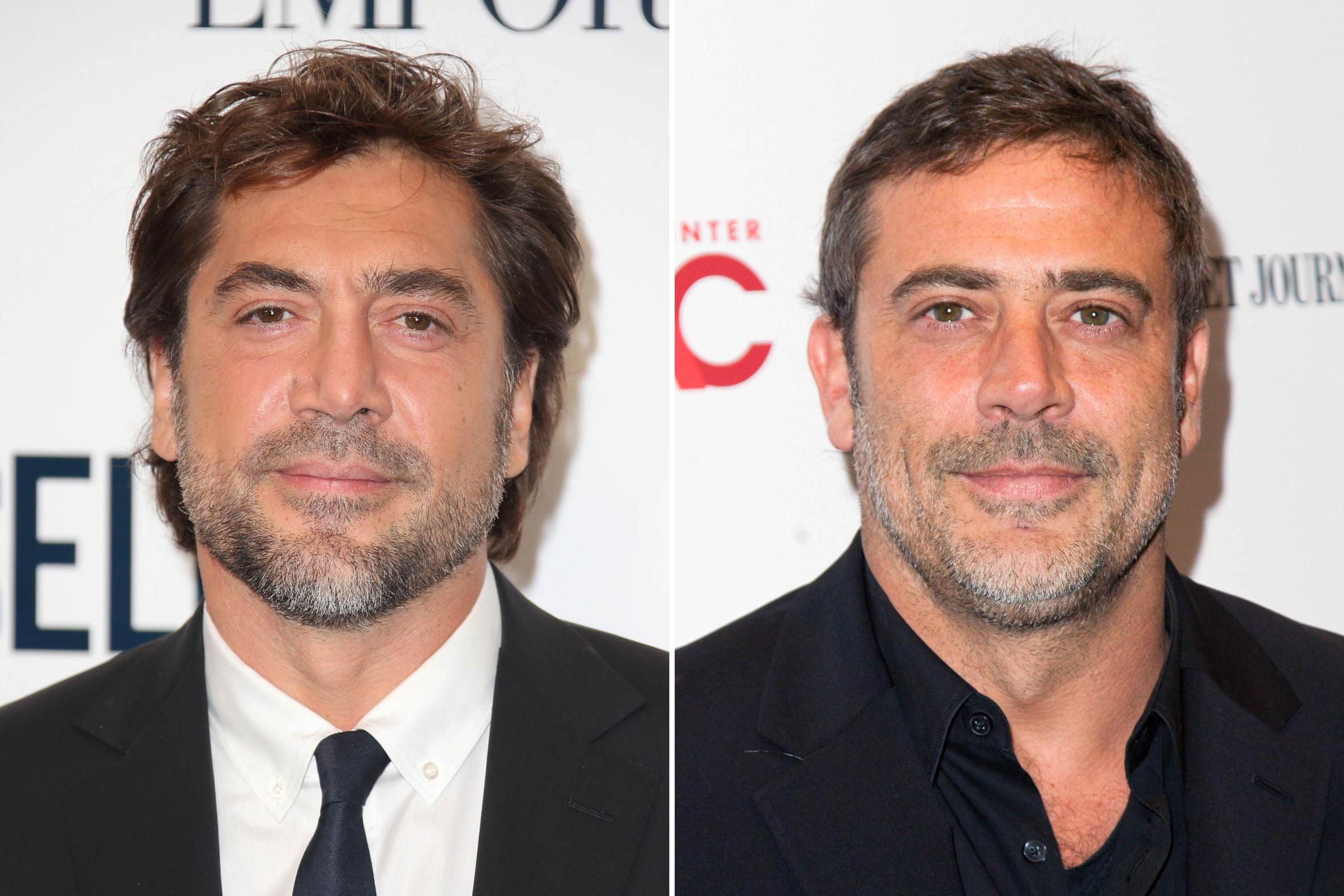

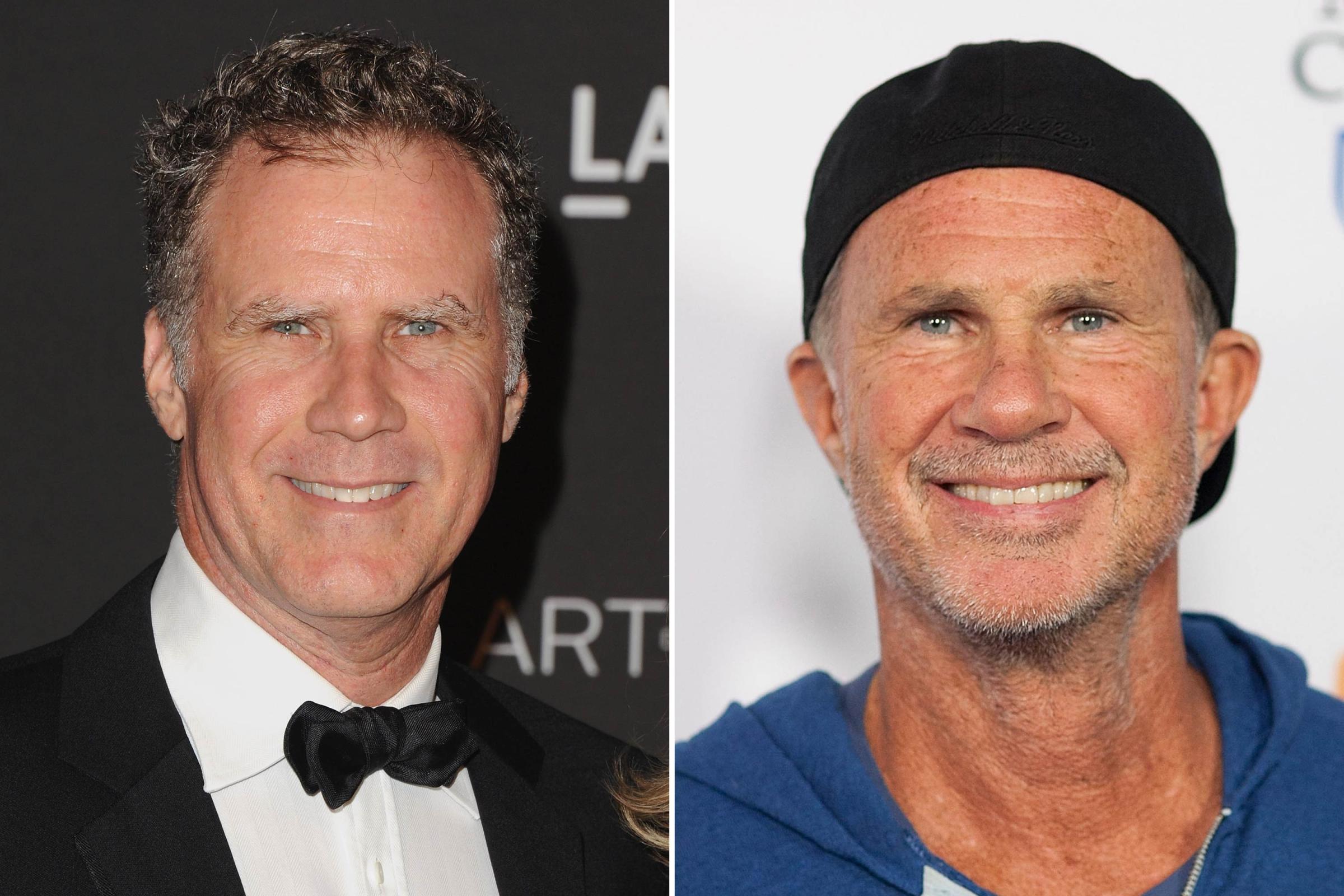

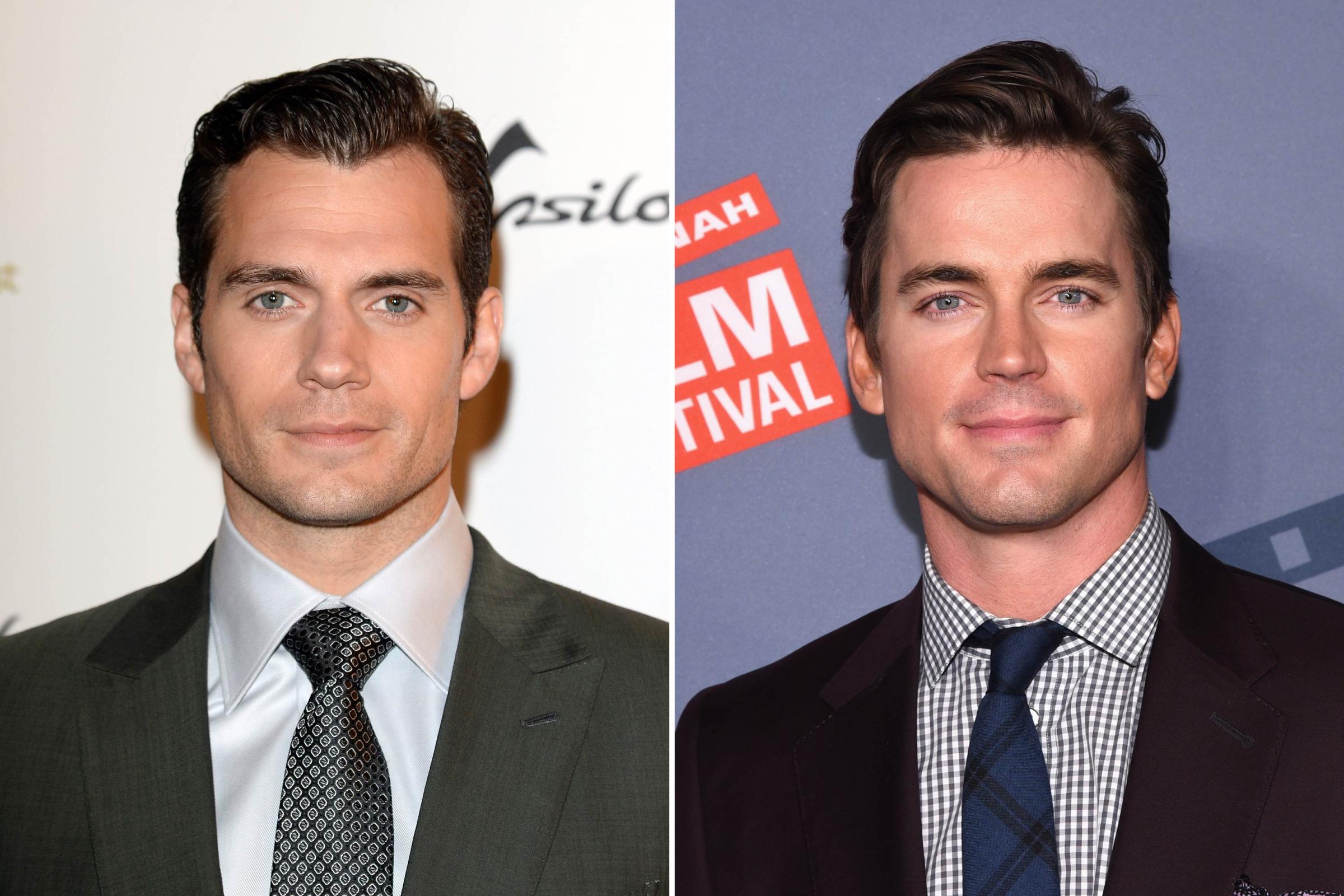

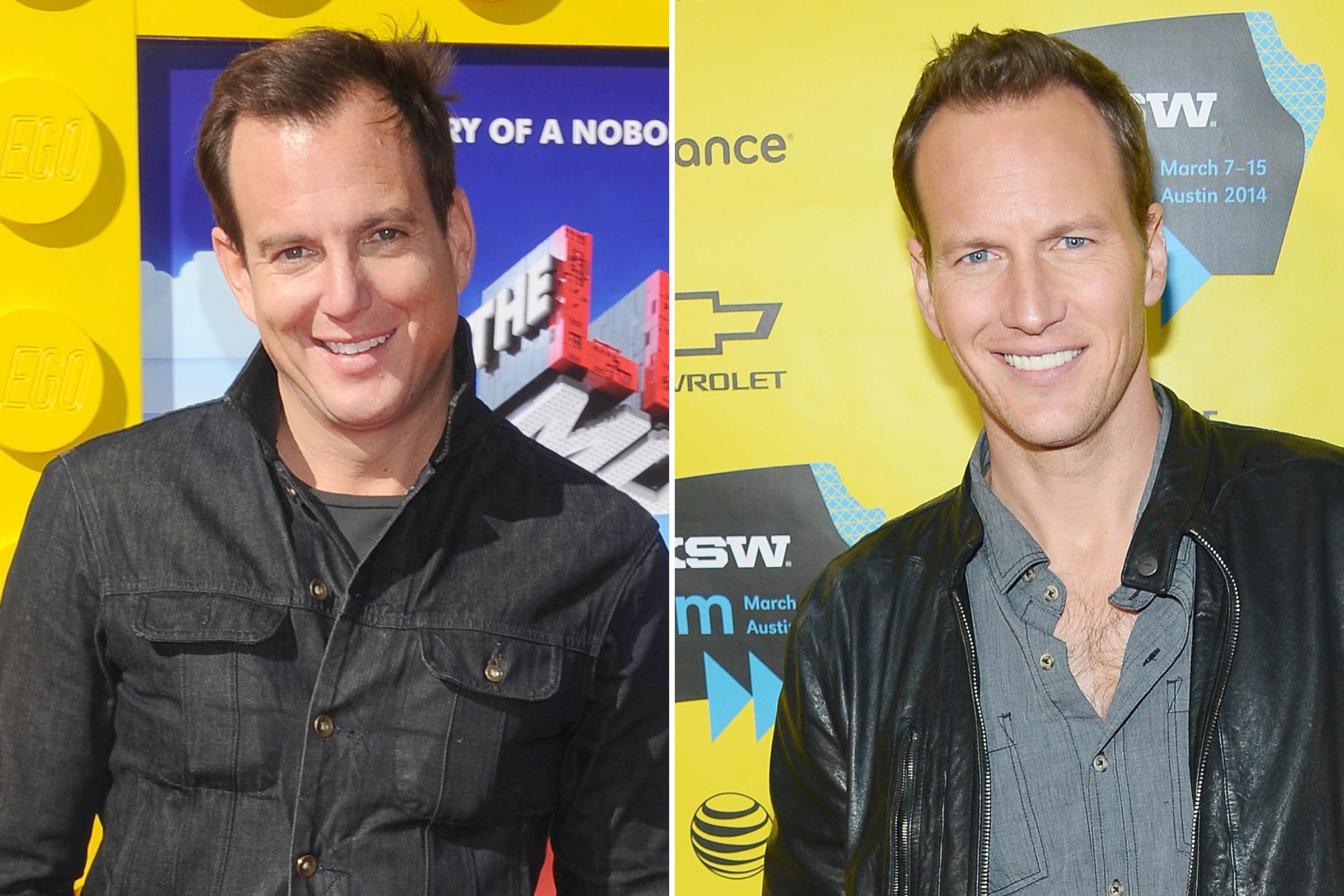

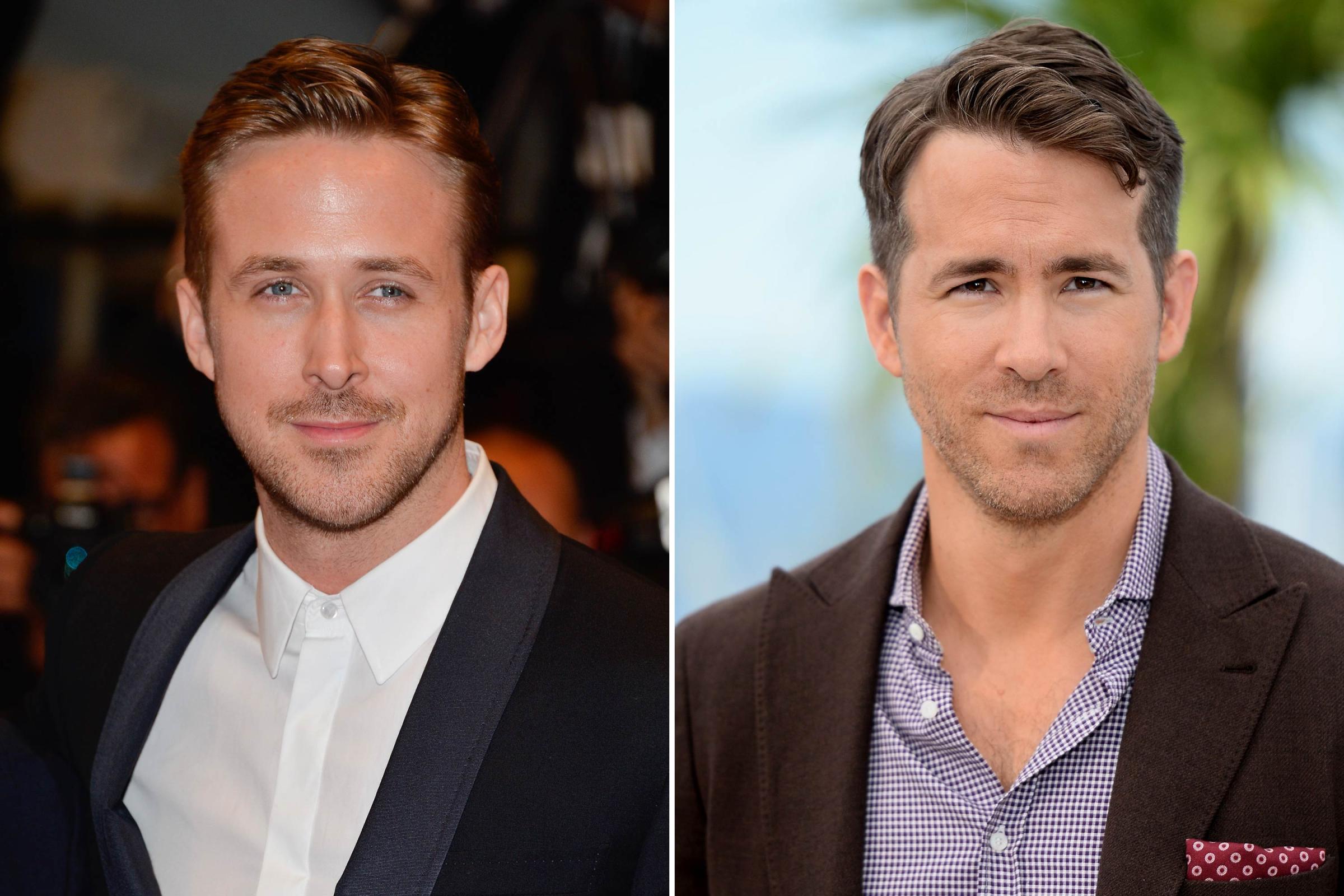

Celebrities Who Look Uncannily Alike

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com