Zócalo Public Square is a magazine of ideas from Arizona State University Knowledge Enterprise.

Most credentialed literary critics disdain it as a grandiose hyperbole, and creative writers tend to speak of it in jest. But for almost 150 years, all of us—writers, readers, cultural trend-watchers—have been obsessed with the idea of the “Great American Novel,” a piece of literature that somehow captures the gestalt of the whirling multitudes that make up our ambitious country at a crucial or defining moment.

What first drew me to the subject of the Great American Novel idea was the strange obstinacy of its persistence. After reading hundreds of candidates and thousands of critical commentaries on those books, it dawned on me that the leading contenders, as a group, offer us something uncannily close to a DNA scan of the American imagination.

We know precisely when the Great American Novel entered public culture as an idea with legs: Jan. 9, 1868, in an essay by a now-forgotten Connecticut novelist, J. W. DeForest. Writing just after the Civil War, DeForest argued that with the country now reunified, fiction writers should stop concentrating on its separate regions, as Nathaniel Hawthorne and James Fenimore Cooper had done, and take in the country’s expansive sweep and social tapestry so as to capture “the national soul.” Revealing his own Yankee provincialism, DeForest proposed that the closest approximation to date was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853).

Yet his essay was well timed. The novel was just coming into high fashion in the United States. The call for the Great American Novel was calculated to appeal to its audience’s acute sensitivity to the perceived gap between the country’s growing industrial might and its relative underperformance in the areas of art and culture.

All this explains the birth of the Great American Novel idea much better than its persistence, long after it became clear that American literature had nothing to apologize for. From 1930 through the 1990s, American writers garnered a disproportionate share of Nobel prizes, and U.S. literature became the dominant player in the English-speaking world. If anxiety about legitimizing our claim to culture were the whole story, by all rights the Great American Novel mantra should have long since disappeared.

One factor in its persistence: Even before the Revolution, the land that became the United States was widely seen in futuristic terms, as a project in the making, founded on the promises that would come to be enshrined in the Declaration of Independence (life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness), yet struggling ever since to make good on them. The overwhelming majority of the dozen or so Great American Novel candidates taken most seriously, from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Toni Morrison’s Beloved, have shunned flag-waving patriotism and concentrated on the gap between promise and delivery. American audiences proverbially love feel-good plots and happy endings, but not when it comes to assessing Great American Novel candidates (or when the Academy picks contenders for the Oscar for “Best Picture,” for that matter).

The nation’s geography and social tapestry has become so much more complicated than when the original 13 rebellious British colonies uneasily allied in the 1770s that it’s become an increasingly formidable challenge to pin down one “American” experience. All this has guaranteed the Great American Novel will remain a future prospect rather than an achieved result.

There are a certain number of specific scripts that have seemed especially promising for generating the 20 or so leading Great American Novel candidates. One is immortalization through multiple retellings of a particular novel’s plotline, like the saga of the embattled heroine of The Scarlet Letter. Another is the family saga that grapples with racial and other social divisions, often turning on a plot of love or friendship across the divides. Still another targets assemblages of characters who dramatize in microcosm the promise and pitfalls of democracy.

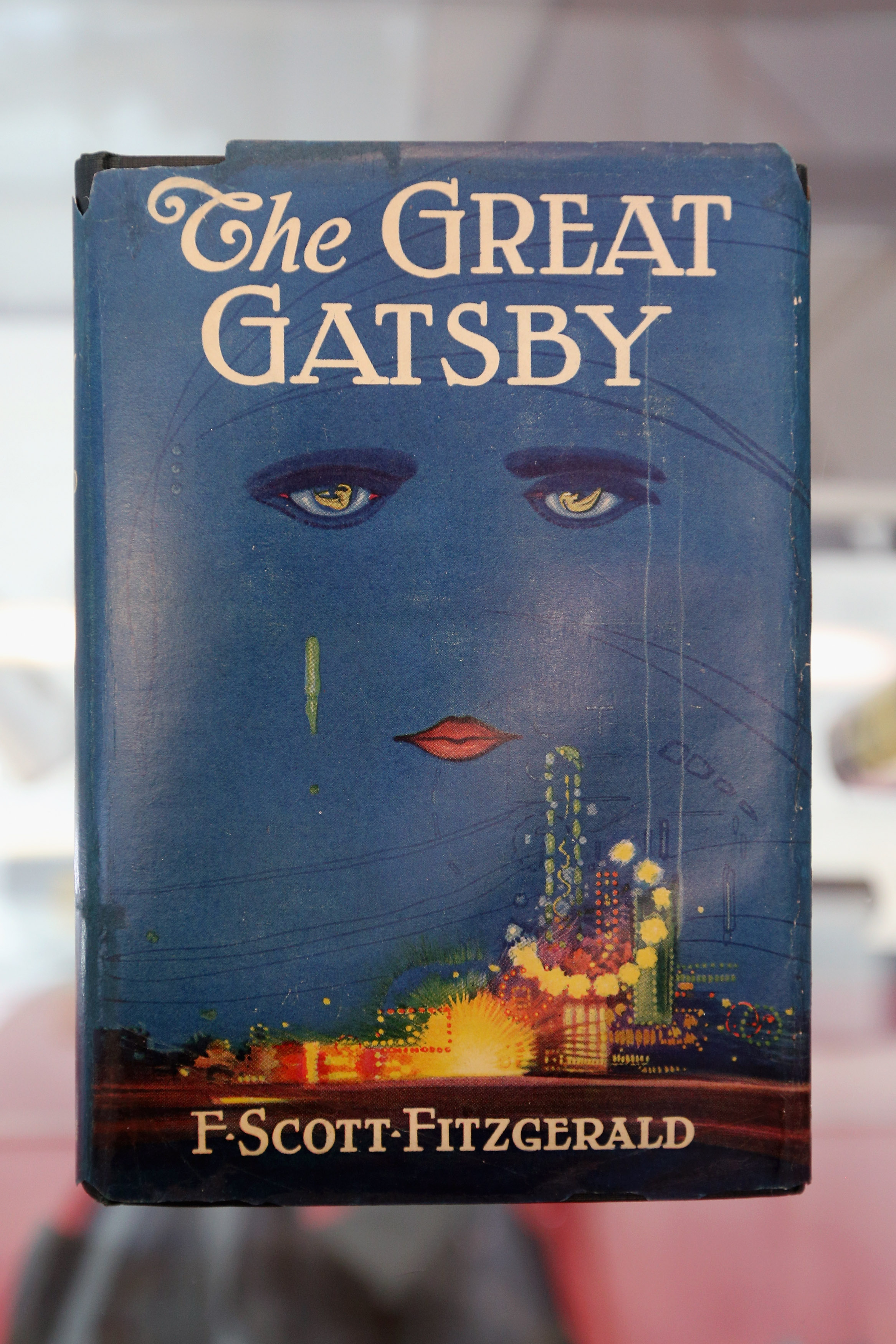

Perhaps the single most popular and durable script of all follows the life struggle of a focal figure who strives to transform himself or herself from obscurity to prominence. Favored candidates, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, unfold as inquests into the promise and perils of the homegrown culture myth of “the self-made man.”

Of course, most Great American Novel scripts are distinctive but not unique to U.S. literature, and the scripts change over time. Before 1930, the protagonists of American up-from novels were overwhelmingly white and American-born; since then, a far greater percentage have been immigrants and people of color.

Whatever that future may be, the vast and expanding field of American fiction isn’t just a haphazard centrifuge. Great American Novel talk reflects the core logics underlying the often sharp, surprising twists and turns of its long history. And key to the impetus that drives the seemingly unkillable dream is the myth of the United States itself as a culture of aspiration, even and indeed especially when those aspirations seem balked or betrayed.

Lawrence Buell is a professor emeritus of American literature at Harvard University. His latest book is The Dream of the Great American Novel. He wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a national conversation hosted by the Smithsonian and Zocalo Public Square.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com