Recently, a Tumblr discussion of Agent Carter — the post-World War II Marvel miniseries currently airing on ABC — turned to the fact that the cast is predominantly white. Unsurprisingly, opinions ran strong. But according to some, there was no reason to get worked up: after all, life in 1940s New York was so segregated that — even in superhero-based fiction — no person of color would be present in the same working or living spaces as a white woman, unless they were a servant.

But, in reality, President Roosevelt’s desegregated Federal employment by executive order in 1941.

That’s why I started the hashtag #HistoricPOC on Twitter and Tumblr. I encouraged fellow users to post pictures of people of color (POC) throughout history. Whether they posted family photos or links to famous images, I wanted there to be an easily accessible visual historic record. It doesn’t matter if someone had any training in history; all that was required were photos and some idea of when they were taken. Users of the tag posted pictures of family members’ celebratory moments, important events and even some of the truly mundane aspects of day-to-day life. All of that history is relevant. All of it is important. All of it is proof that they were there too. We cannot erase the people who lived through the past from the spaces they inhabited, and it is incredibly important not to whitewash the past as that can only lend itself to racist myths about the roles of POC in creating and sustaining society.

At the time Roosevelt wrote Executive Order 8802 and established Fair Employment Practice in the Defense Industries, federal employment was not fully segregated despite the best efforts of some of his predecessors. People like Mary Church Terrell and W.E.B. DuBois had fought President Woodrow Wilson’s efforts to implement Jim Crow laws in the federal service. Black men (like Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and William Dawson) were in the House of Representatives at a time when current popular media — in a bizarre reflection of the Jim Crow mores that made Blackface more popular than Black people in many movies — would have you believe that the past was all white, unless the topic is the oppression of POC. There is more to our history than the pain of legally enfranchised brutality depicted in Roots, Selma, or The Help. To show only show those aspects of history might make a modern viewer think that the people of color of the past had no power to effect change. Nothing could be further from the truth: the roots of any liberation enjoyed by modern marginalized people can be found in the work done by those who came before us, who (whether we are taught it or not) stood up against oppression in ways that are still impacting us today.

Was the agency of Black people — the agency of all people of color — limited during Jim Crow? Absolutely. It is still limited by structural racism. However, a history that paints us as objects with no power is a false one indeed. Erasure is not equality, and we need to see what happened in the past, to know how we should engage in the present and the future. There is an old saying that history is written by the victors. It’s a great shorthand for the reality that what we think we know of the past is framed by the people teaching us about it, whether with a textbook that skims right over the details of life in between major events like slavery and the end of Jim Crow laws, or media that portray the past as the province of a particular ethnic group. The reality is most people only know as much history as they’ve been taught before the age of 18. After high school, any further study of history is largely optional; interests can be heavily slanted towards one area with no need to learn more about anyone or anything else.

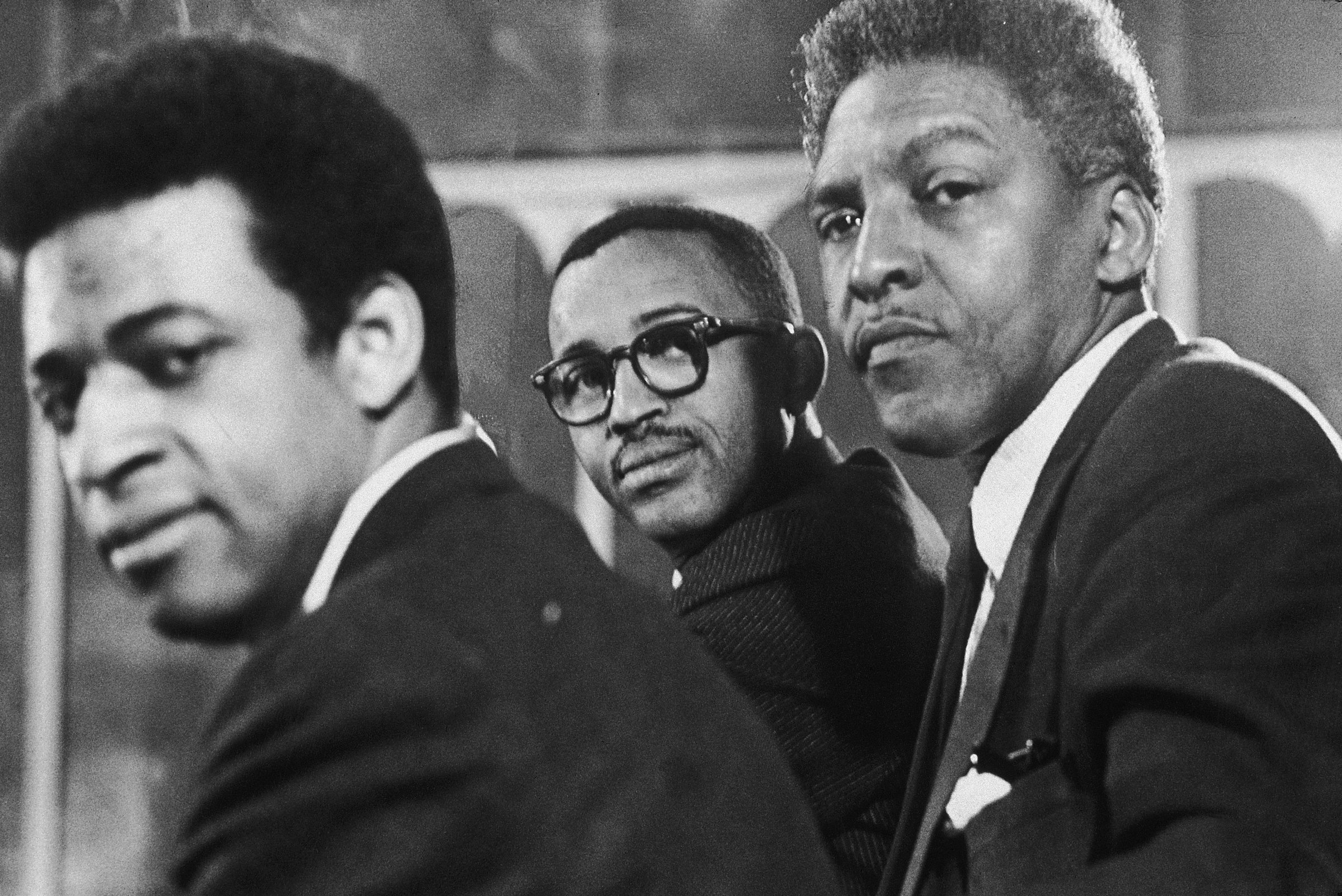

Thus, the fact that Martin Luther King Jr. was born only six months before Anne Frank escapes most people simply because the two icons are never situated in the same lessons. Others who were instrumental in changing the world are erased simply because they aren’t spoken of at all in textbooks. We may hear more about Rosa Parks than Claudette Colvin, but both were instrumental in effecting change. The same is true of Bayard Rustin, whose sexual orientation meant that even those who worked directly with him rarely spoke publicly about the importance of his contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. We may know that Josephine Baker danced in a banana skirt while never hearing that she was awarded the Croix de guerre (Cross of War), or that she was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by General Charles de Gaulle for her work with the French Resistance during World War II.

Because of how history is taught, we tend to think of it as discrete events, even though it is all interconnected. #HistoricPOC isn’t a comprehensive look at history, but an effort to use social media to bring out more facts that might otherwise be ignored. History was written by the victors, but now anyone can document the past, and because Twitter and other social media sites are being archived, the use of the hashtag can make that data more accessible to the casual researcher. To know your history — to really know it — is to be proud of where you came from, and to be equipped with a certainty that even the smallest of steps forward can make a long term difference.

As events unfold in the current fight against police brutality in marginalized communities, a truer representation of history can be inspirational — and, more importantly, it can show us how communities worked together to achieve common goals. There is no fairness in the workplace without the labor movement and the Civil Rights Movement making their individual and joint contributions. Nor does any movement happen solely because of the efforts of one person. Rosa Parks, Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X, James Boggs, Grace Lee Boggs, Josephine Baker, Ozzie Davis, Ruby Dee and Harry Belafonte are the names you might recognize, but there were thousands of people working together to make change happen. A history that erases the importance of money contributed by entertainers, domestic workers and policy players is one that dehumanizes and demeans their sacrifices. Respectability might make some historical figures more appealing than others, but as we are seeing right now in Ferguson, Ohio, Chicago, New York, and so many other places, respectability isn’t required to do good and meaningful work against institutional oppression.

#HistoricPOC is written by all of us who want to participate, about all of our ancestors — not just the ones who made it into the history books.

Mikki Kendall is co-editor of hoodfeminism.com, cultural critic, historian by training, and occasional feminist by choice.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com