Writing in the New York Review of Books last year, Carl Djerassi declared that with the invention of the birth control pill, “sex became separated from its reproductive consequences” and “changed the realities of human reproduction.” Djerassi would know. The pioneering chemist, who died on Jan. 30 of complications from liver and bone cancer at the age of 91, was dubbed the father of the birth control pill after he created the key ingredient used in oral contraceptives.

The importance of his discovery — and the dogged research of numerous other scientists — can’t be understated. Today, a staggering 99% of American women of childbearing age report using some form of contraception at one time or another.

Yet while Djerassi’s discovery and other modern advancements have led to the ubiquitous use of safe and effective contraception, pregnancy prevention has a long and determined history. As Jonathan Eig writes in his book The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution, “For as long as men and women have been making babies, they’ve been trying not to.”

Proto-Prophylactics

Not that every historical effort was all that effective. Some methods are still used today, such as coitus interruptus — or “pulling out” — which was referenced in the Old Testament, but have never been a reliable form of pregnancy prevention. And other methods seem, by today’s standards, straight-up bizarre. In ancient Egypt, for example, around 1500 BC, women would mix honey, sodium carbonate and crocodile dung into a pessary — a thick, almost solid paste — and insert it into their vaginas before sex. (Crocodile dung was later found to possibly increase the likelihood of getting pregnant, due to its effects on the body’s pH levels.) In ancient China, concubines are thought to have used a drink of lead and mercury in order to prevent pregnancy. (Possible side effects: sterility, brain damage, kidney failure and death.) In the year 200, the Greek gynecologist Soranus advised women to abstain from sex during menstruation, which he mistakenly believed to be their most fertile time of month. (Not true.) He also recommended that women hold their breath during intercourse, followed by sneezing afterwards to prevent sperm from entering the womb. (Just silly.) In 10th-century Persia, women were told to jump backwards seven or nine times after intercourse to dislodge any sperm, as those were believed to be magical numbers. And in the Middle Ages in Europe, women were advised to tie the testicles of a weasel to their thighs or around their necks during intercourse. (Really.)

Yet it wasn’t all a shot in the dark. Many researchers today believe that several archaic methods of birth control actually had the dual perks of being somewhat effective and not lethal. This is perhaps not so surprising considering that certain methods were passed along from one woman to another. For instance, the ancient Egyptians weren’t completely off the mark with their pessaries: some documents reveal that women would also use pessaries made with acacia gum, which was later found in 20th-century studies to have spermicidal effects. Several other plants used in the ancient world were later found to have contraceptive qualities as well.

Sex Ed Books Through the Ages

And it wasn’t just plants. A cave painting that researchers believe could be 15,000 years old, found in France, depicts what some think is the first illustration of a man wearing a condom. The condom also shows up in legends that date back to 3000 BC, in which King Minos of Crete — son of Zeus and Europa — would use goat bladders for that purpose.

Later, the European doctor Gabriel Fallopius, for whom the fallopian tubes are named, suggested a linen version, prompted by a syphilis epidemic that spread across the continent in the 1500s. In Giacomo Casanova’s memoirs, written in the late 18th century, he takes credit for inventing a primitive version of the cervical cap, when he describes using partly squeezed lemon halves during sex. (A painting of the Italian writer also exists where he appears to be blowing into a condom-like prophylactic, but researchers believe that Casanova’s covers were for protection from venereal disease, not pregnancy.)

Condoms turned another technological corner in the year 1844, when American manufacturing engineer Charles Goodyear patented the vulcanization of rubber, which he had invented five years earlier. The move led to the mass-production of rubber condoms and the appearance of rubber cervical caps. It would be several decades before cervical caps — and later diaphragms — would catch on in the U.S., where the earliest rubber diaphragms were known as “womb veils.” Condoms caught on much more quickly. The first advertisement for the condom appeared in The New York Times in 1861, for a brand called Dr Power’s French Preventatives. The advertisement’s tagline read: “Those who have used them are never without them.”

Birth-Control Backlash

But just when it looked as if contraceptives were taking off — becoming not only safe and effective, but also more widely available — an American post inspector named Anthony Comstock began crusading against obscenity. His campaign led to the Comstock Act, passed in 1873, which banned the spread of information about contraceptives in the United States — even from doctors.

The 20th century would eventually see the most advanced and revolutionary development of birth control in history, but at the start of the century the phrase “birth control” wasn’t part of the common parlance. Margaret Sanger — a determined nurse and activist who would revolutionize reproductive rights in America — first coined the phrase in 1914 with the launch of a monthly newsletter called The Woman Rebel. The newsletter offered information about birth control and was a flagrant challenge to the country’s obscenity laws. It wasn’t long before Sanger was indicted for breaching the obscenity laws and fled the country to avoid trial. By 1916, Sanger was back and opening the first family-planning clinic in the U.S. It was shut down within a week and a half. Five years on, Sanger founded the American Birth Control League, which would later become the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Neither legal restrictions, nor religious condemnation—during the 1930s, Pope Pius XI declared that using birth control was a “grave sin”—could actually stop women from trying to prevent pregnancy. In 1935, TIME reported that “[d]espite furtiveness, commerce in contraceptives has become big business. More than 300 manufacturers today are engaged in it…. Three ‘feminine hygiene’ manufacturers last year spent $250,000 advertising in general magazines alone.”

Some advertisements for products marketed to women emphasized their “feminine” uses, with obvious euphemisms for contraceptives. Throughout the 1920s, even Lysol was advertised as a product that could “protect your married happiness” with a series of terrifying ads, depicting desperate women trying to keep the family harmony—so desperate, in fact, they were willing to use a household cleaner as a douche. Lysol didn’t have any contraceptive qualities—and could actually be quite harmful when inserted into the body—but that wasn’t the impression given by the company‘s marketing campaign. Another household product that many believed could prevent pregnancy was Coca-Cola. (Unsurprisingly, it did not actually prevent unwanted pregnancies: though later research suggested that a douche of cola did kill sperm, it didn’t work fast enough.)

In 1937, headway in Sanger’s fight was made when the American Medical Association officially recognized birth control as a legitimate part of doctors’ practice. A year later a judge lifted the federal obscenity ban on birth control, though laws against contraception remained on the books in most states. America went from 55 birth control clinics in 1930 to more than 800 in 1942.

The Pill Arrives

By the 1950s, Sanger landed on a better way to serve that demand. She approached biologist Gregory Pincus — who had something of a reputation as a Dr. Frankenstein-like character, due to his experiments with in-vitro fertilization of rabbits — and asked him to conduct research on the use of hormones for contraception. Unbeknownst to Sanger and Pincus, a scientist in Mexico City had already had success creating a progesterone pill, synthesized from wild yams, which could block ovulation. That scientist was Carl Djerassi, then just a twenty-something but already the associate director of research at the pharmaceutical company Syntex.

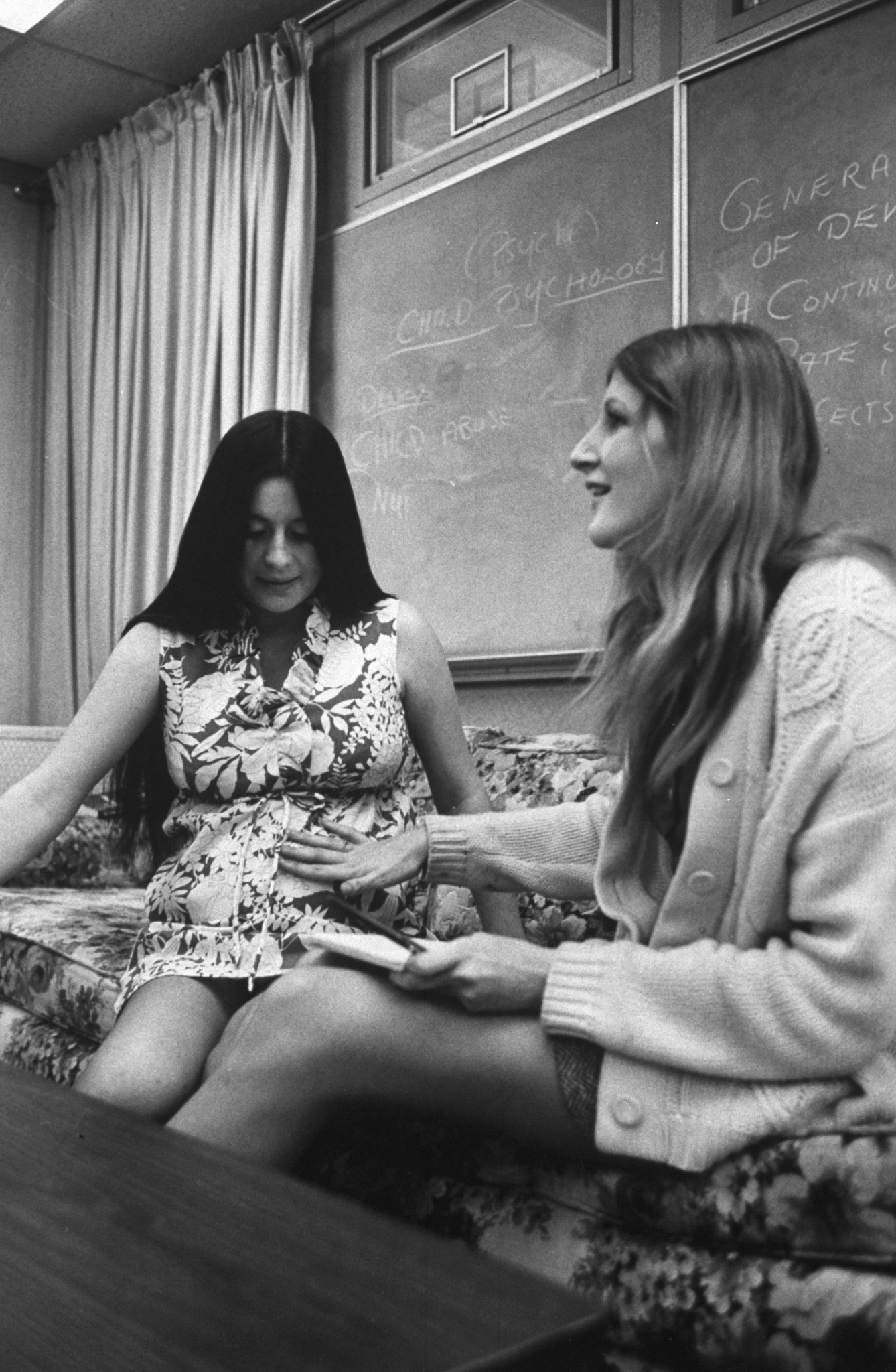

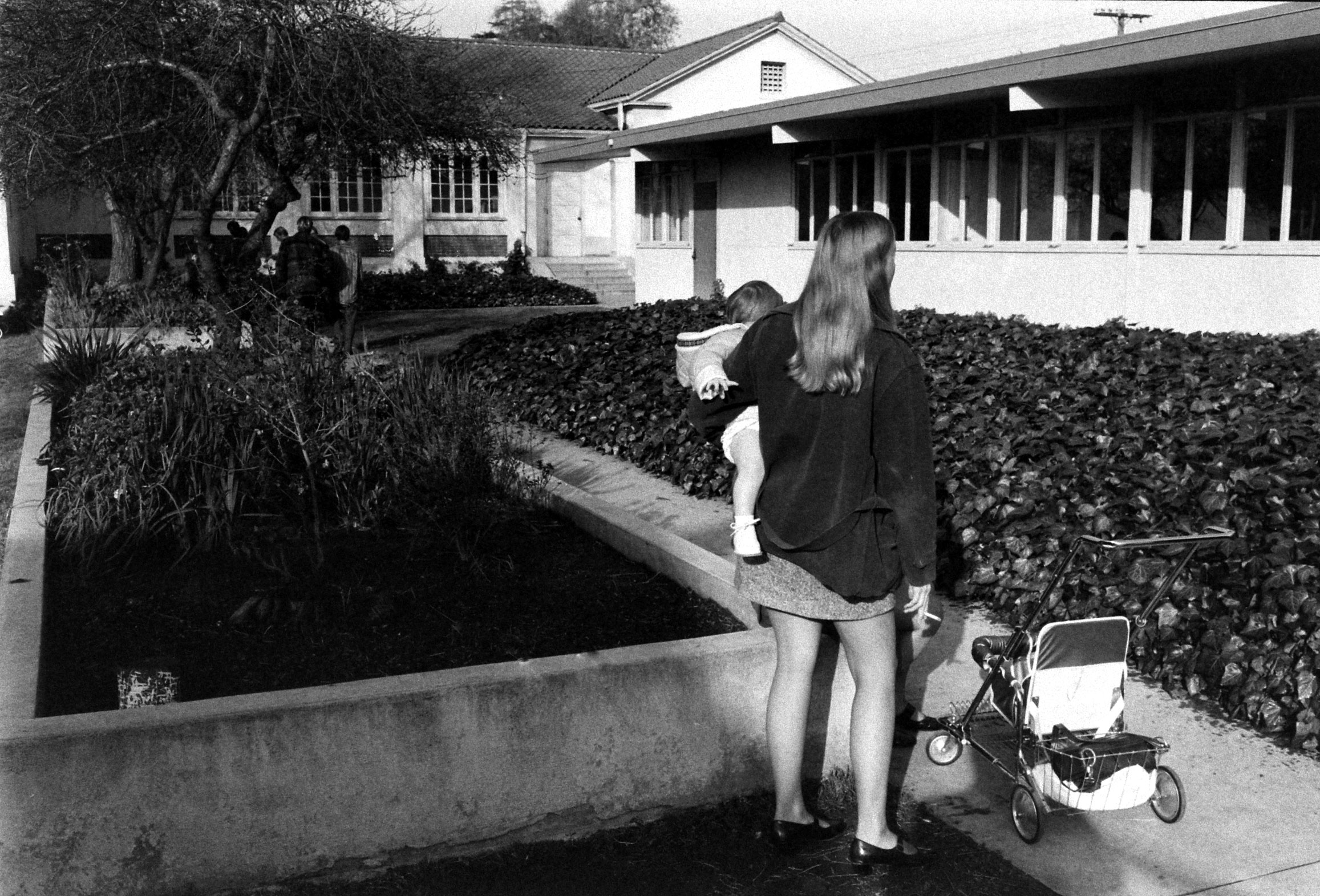

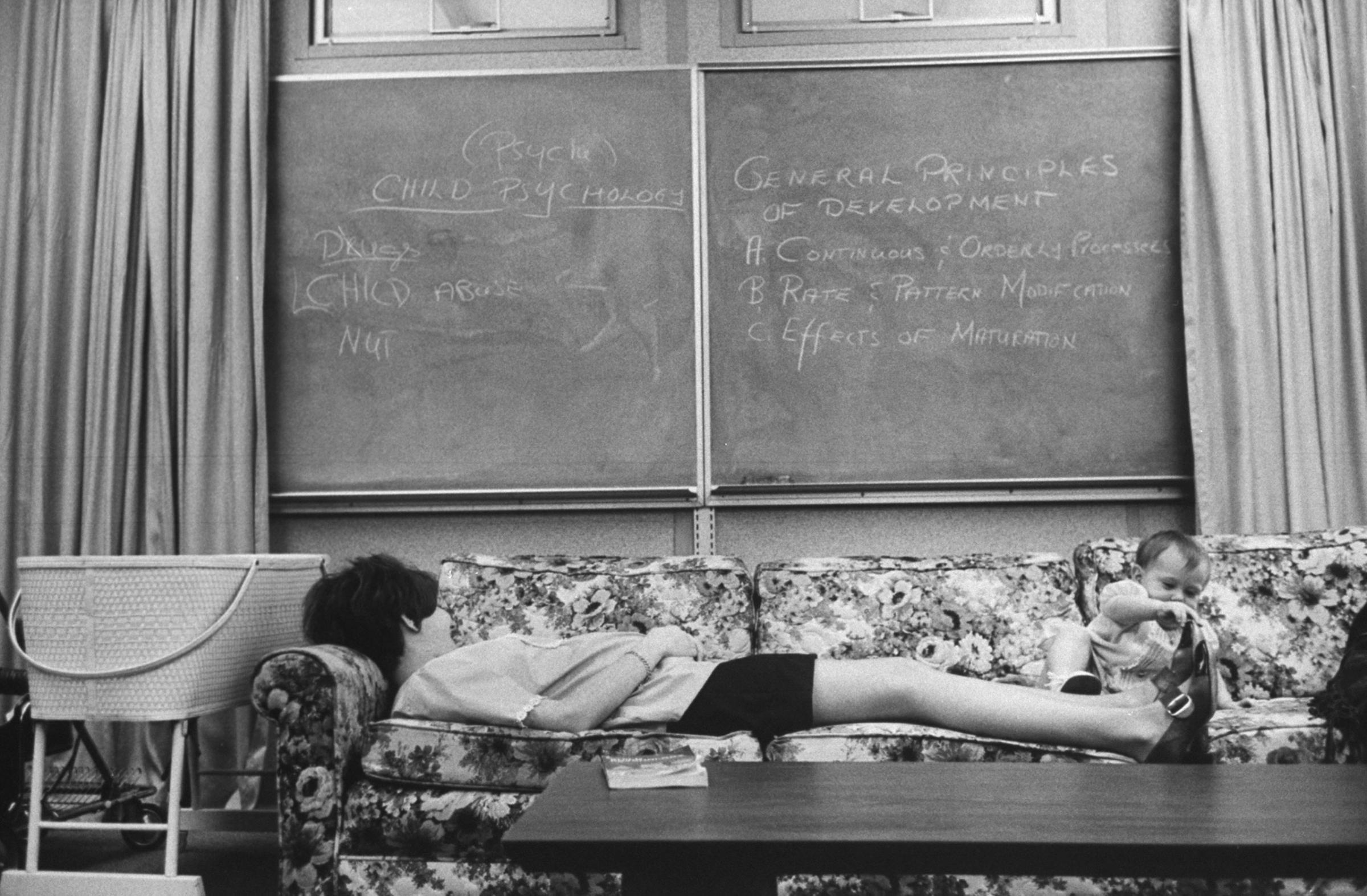

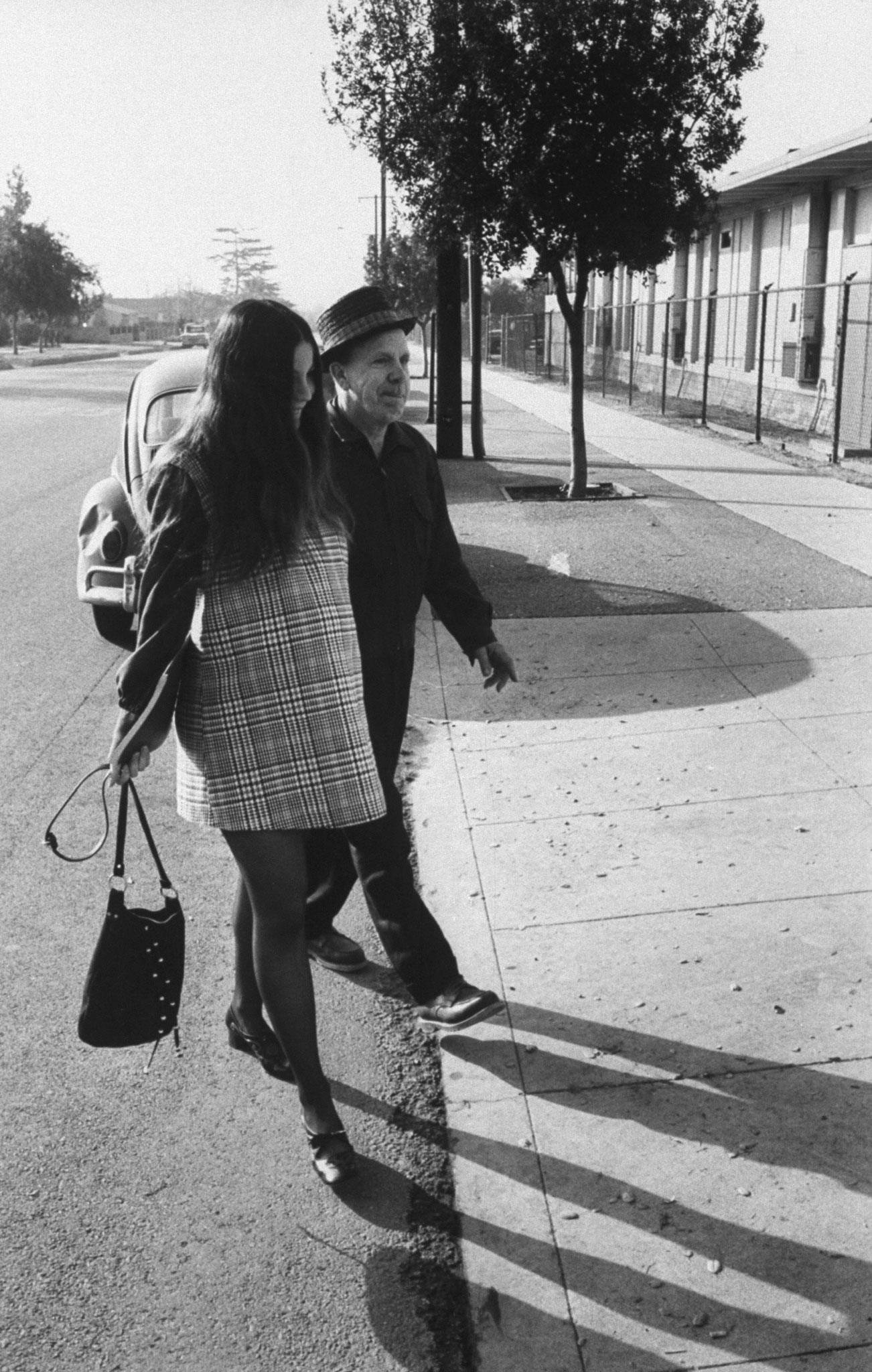

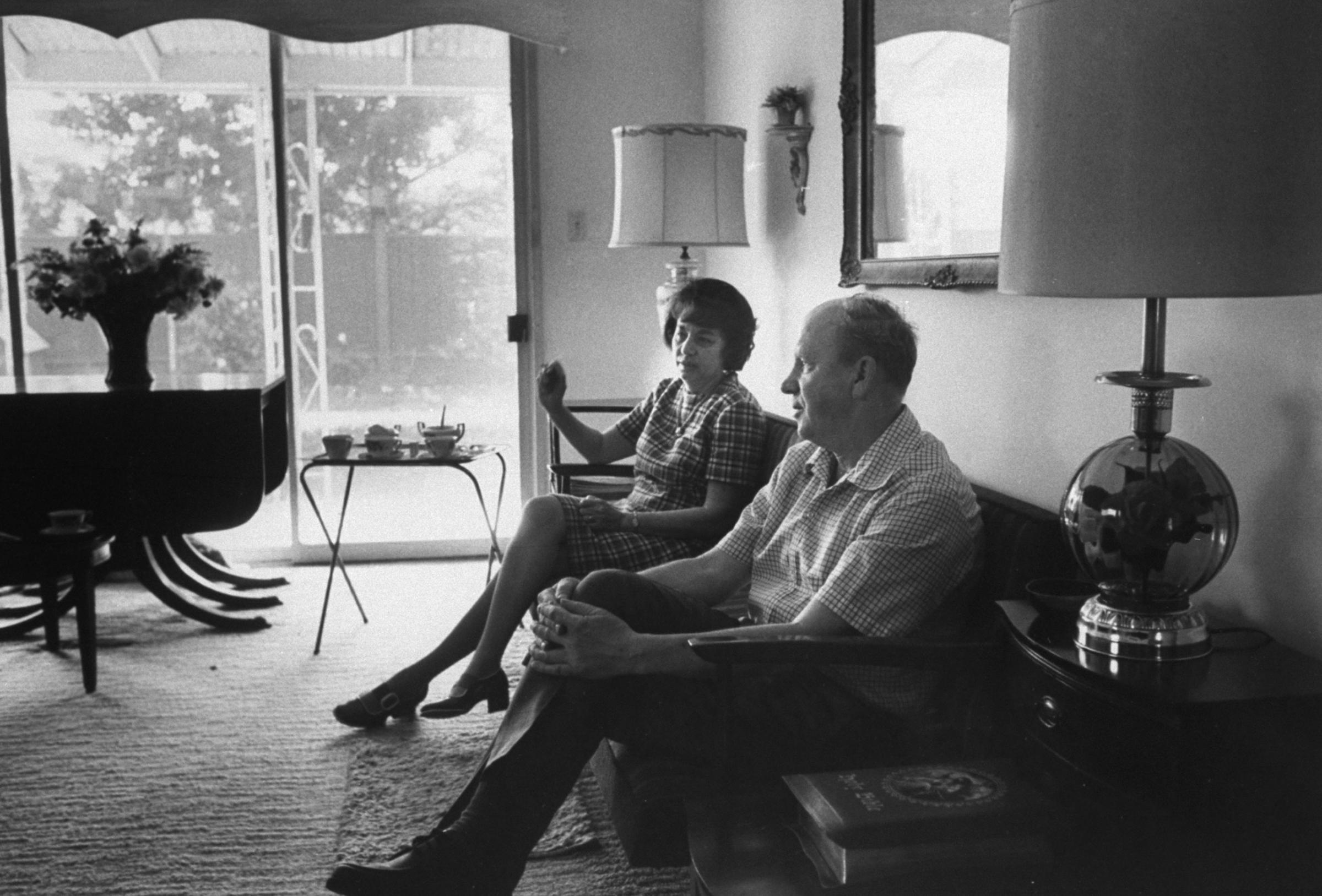

Fighting Teen Pregnancy: Portrait of a Radical High School Program, 1971

With funding from Katherine McCormick, a wealthy widow and dedicated feminist, Pincus had also begun developing and testing a synthetic hormone and found that it could suppress ovulation in animals. A gynecologist named John Rock then began testing the hormone on women. In 1956, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the hormone pills for menstrual disorders, such as irregular periods or PMS. Promoting birth control was still illegal in many states, but as TIME winkingly noted in 2010, the late ’50s tellingly saw “a sudden epidemic of menstrual irregularity among women across the U.S.”

Then came the landmark date, marking the biggest change to America’s contraceptive potential in history. On May 9, 1960, the FDA approved Enovid, an oral contraceptive pill released by G.D. Searle and Company. By 1965, almost 6.5 million American women were on “The Pill,” the oral contraceptive’s enduring vague nickname, which is thought to have stemmed from women requesting it from their doctors as discreetly as possible. That same year, the Supreme Court struck down state laws that prohibited contraception use, though only for married couples. (Unmarried people were out of luck until 1972, when birth control was deemed legal for all.)

Even by 1966 the Pill’s effects were apparent. That year, TIME wrote, “No previous medical phenomenon has ever quite matched the headlong U.S. rush to use the oral contraceptives now universally known as ‘the pills.’” Indeed, by the time 1973 rolled around, a whopping 70% of married women between the ages of 15 and 44 were using some form of contraception.

The Pill was an international revolution as well. In 1967, TIME reported that despite the Pill’s necessarily strict routine, uneducated women could still manage: “[The] latest reports show that illiterate women who can’t count can still take their pills on schedule. In Pakistan, Denver’s Dr. John C. Cobb got dozens of them to do it, simply by starting them on the night of the new moon. In semiliterate Taiwan, where IUDs have won wide acceptance, more and more women are switching to the pills. The number of users outside the U.S. is about 5,000,000, and the figure is rising.”

Not that the Pill was without critics. The fact that its rise coincided with second-wave feminism and the sexual revolution meant that many people pointed to the contraceptive as the trigger that changed society. (Many researchers have pointed out that cultural views on sexuality and women’s roles were shifting well before the Pill was introduced.) Some African-American leaders were especially critical of the Pill, claiming that it was being peddled in their community for the purpose of a “black genocide.” But nothing stopped the Pill from catching on. Today, more than 100 million women around the world use the Pill in order to prevent pregnancy. And that’s not counting the women using other safe and effective forms of birth control, from DepoProvera and the NuvaRing to the contraception patch and the intrauterine device (IUD), which is considered by many health care experts to be one of the best forms of birth control available.

The Future of Birth Control

Yet access to safe and effective birth control still isn’t a universal privilege. A report from the Guttmacher Institute in 2012 found that around 222 million women in developing countries want to use birth control but aren’t currently able to access modern contraceptives.

Even in the U.S., there has been a political push to restrict access. The rise of “conscience clauses” has also meant that hospital employees, pharmacists and employers with religious views on birth control can refuse to fill prescriptions or cover employees’ coverage for contraception.

History — both ancient and more recent — has shown that women (and men) will risk their lives or reputations for effective birth control. Restricted access to contraceptives doesn’t necessarily mean that women won’t be able to prevent pregnancies, but, like the ancient Egyptians and Chinese, they just might resort to methods that could be harmful. That hasn’t changed, but thanks to the dogged determination of activists, such as Sanger, and the pioneering research by scientists and physicians, such as Djerassi, that level of risk seems like the most preventable thing of all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com