Correction appended Jan. 30, 2015

Give climate change credit for one thing: it’s endlessly versatile. There was a time we called it global warming, which meant what it said: the globe would get warmer. It was only later that we appreciated that a planet running a fever is just like a person running a fever, which is to say it has a whole lot of other symptoms: in this case, droughts, floods, wildfires, habitat disruption, sea level rise, species loss, crop death and more.

Now, you can add yet another problem to the climate change hit list: volcanoes. That’s the word from a new study conducted in Iceland and accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters. The finding is bad news not just for one comparatively remote part of the world, but for everywhere.

Iceland has always been a natural lab for studying climate change. It may be spared some of the punishment hot, dry places like the American southwest get, but when it comes to glacier melt, few places are hit harder. About 10% of the island nation’s surface area is covered by about 300 different glaciers—and they’re losing an estimated 11 billion tons of ice per year. Not only is that damaging Icelandic habitats and contributing to the global rise in sea levels, it is also—oddly—causing the entire island to rise. And that’s where the trouble begins.

Eleven billion tons of ice weights, well, 11 billion tons; as that weight flows away, the underlying land decompresses a bit. In the new paper, investigators from the University of Arizona and the University of Iceland analyzed data from 62 GPS sensors that have been arrayed around Iceland—some since as long ago as 1995, others only since 2006 or 2009. But all of the sensors told the same story: Iceland is rising—or rebounding as geologists call it—by 1.4 in. (35 mm) per year.

That’s much faster than the investigators expected, and other studies of the Icelandic crust show that the speed began to pick up around 1980, or just the time that glacier melt accelerated, too. “Our research makes the connection between recent accelerated uplift and the accelerated melting of the Icelandic ice caps,” said Kathleen Compton of the University of Arizona, a geoscientist and one of the paper’s co-authors, in a statement.

In some respects that shouldn’t be a bad thing: yes, an inch and a half a year is fast on a geologic scale, but in the modern, climate-disrupted world, a rising coastline might be just what an island needs to keep up with rising sea levels. The problem is, Iceland isn’t just any island, it’s a highly geologically active one, with a lot of suppressed volcanic anger below the surface. The last thing you want to do in a situation like that is take the lid off the pot.

“As the glaciers melt, the pressure on the underlying rocks decreases,” Compton said in an e-mail to TIME. “Rocks at very high temperatures may stay in their solid phase if the pressure is high enough. As you reduce the pressure, you effectively lower the melting temperature.” The result is a softer, more molten subsurface, which increases the amount of eruptive material lying around and makes it easier for more deeply buried magma chambers to escape their confinement and blow the whole mess through the surface.

“High heat content at lower pressure creates an environment prone to melting these rising mantle rocks, which provides magma to the volcanic systems,” says Arizona geoscientist Richard Bennett, another co-author.

Perhaps anticipating the climate change deniers’ uncanny ability to put two and two together and come up with five, the researchers took pains to point out that no, it’s not the very fact that Icelandic ice sits above hot magma deposits that’s causing the glacial melting. The magma’s always been there; it’s the rising global temperature that’s new. At best, only 5% of the accelerated melting is geological in origin.

Icelandic history shows how bad things can get when the ice thins out. During the last deglaciation period 12,000 years ago—one that took much longer to unfold than the current warming phase turbocharged by humans—geologic records suggest that volcanic activity across the island increased as much as 30-fold. Contemporary humans got a nasty taste of what that’s like back in 2010 when the volcanic caldera under the Eyjafjallajökull ice cap in southern Iceland blew its top, erupting for three weeks from late March to mid-April and spreading ash across vast swaths of Europe. The continent was socked in for a week, shutting down most commercial flights.

If you enjoyed that, there’s more of the same coming. At the current pace, the researchers predict, the uplift rate in parts of Iceland will rise to 1.57 in. (40 mm) per year by the middle of the next decade, liberating more calderas and leading to one Eyjafjallajökull-scale blow every seven years. The Earth, we are learning yet again, demands respect. Mess with it and there’s no end to the problems you create.

An earlier version of this story misstated the annual rate of land rebound in the coming decade. It is 1.57 in.

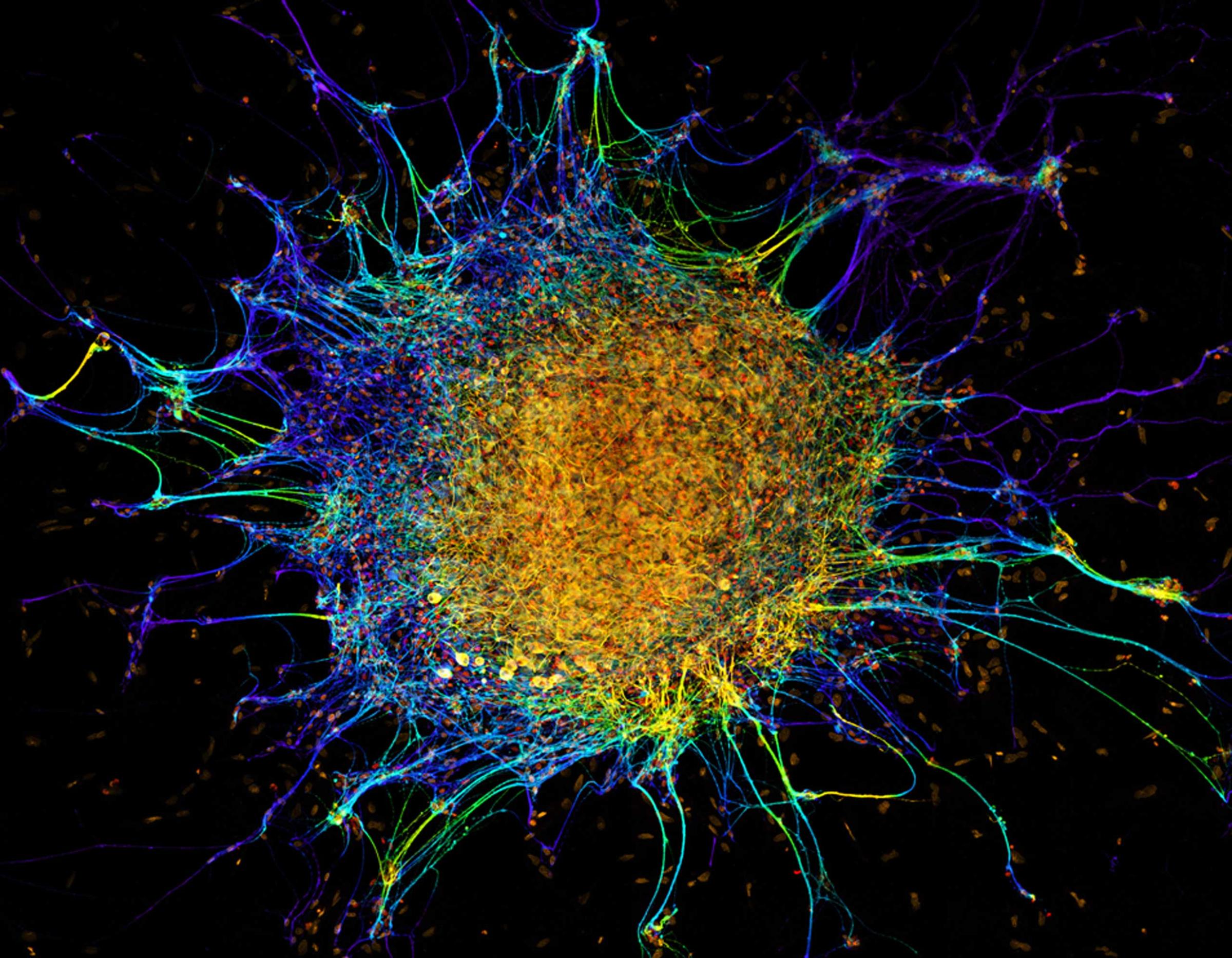

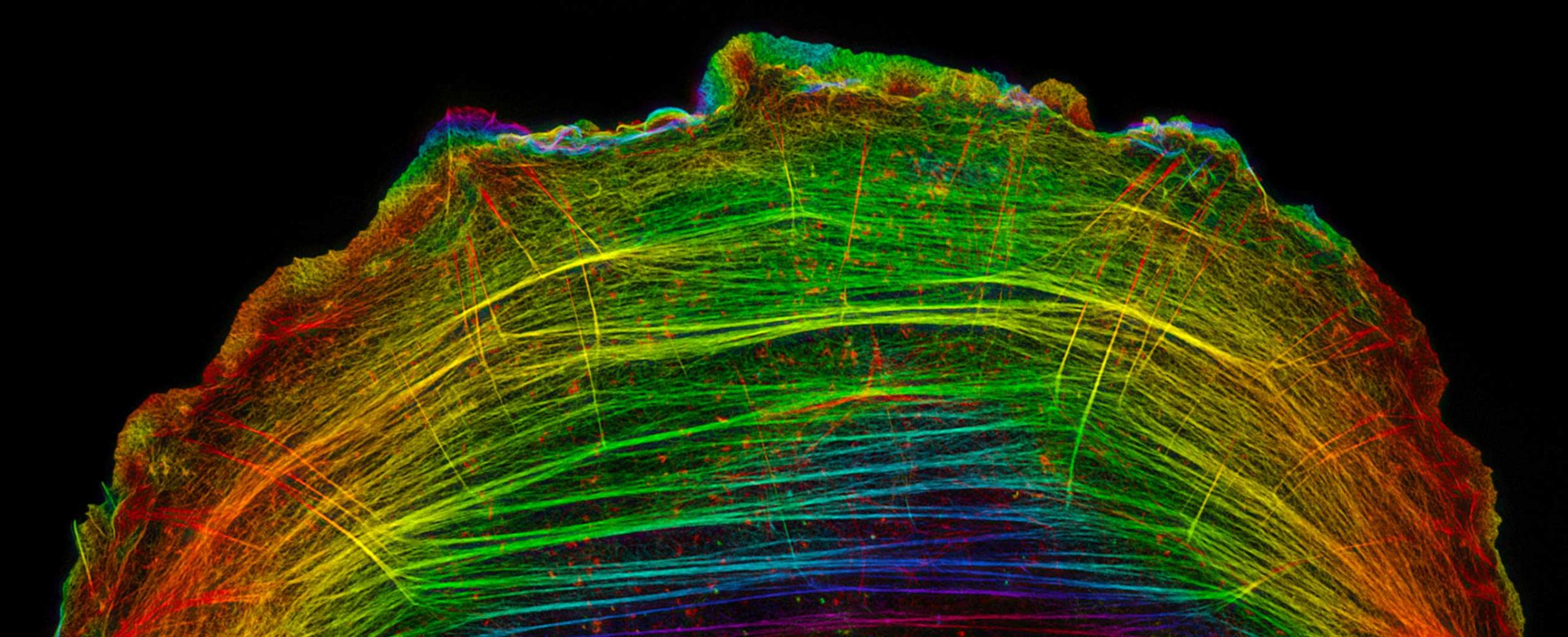

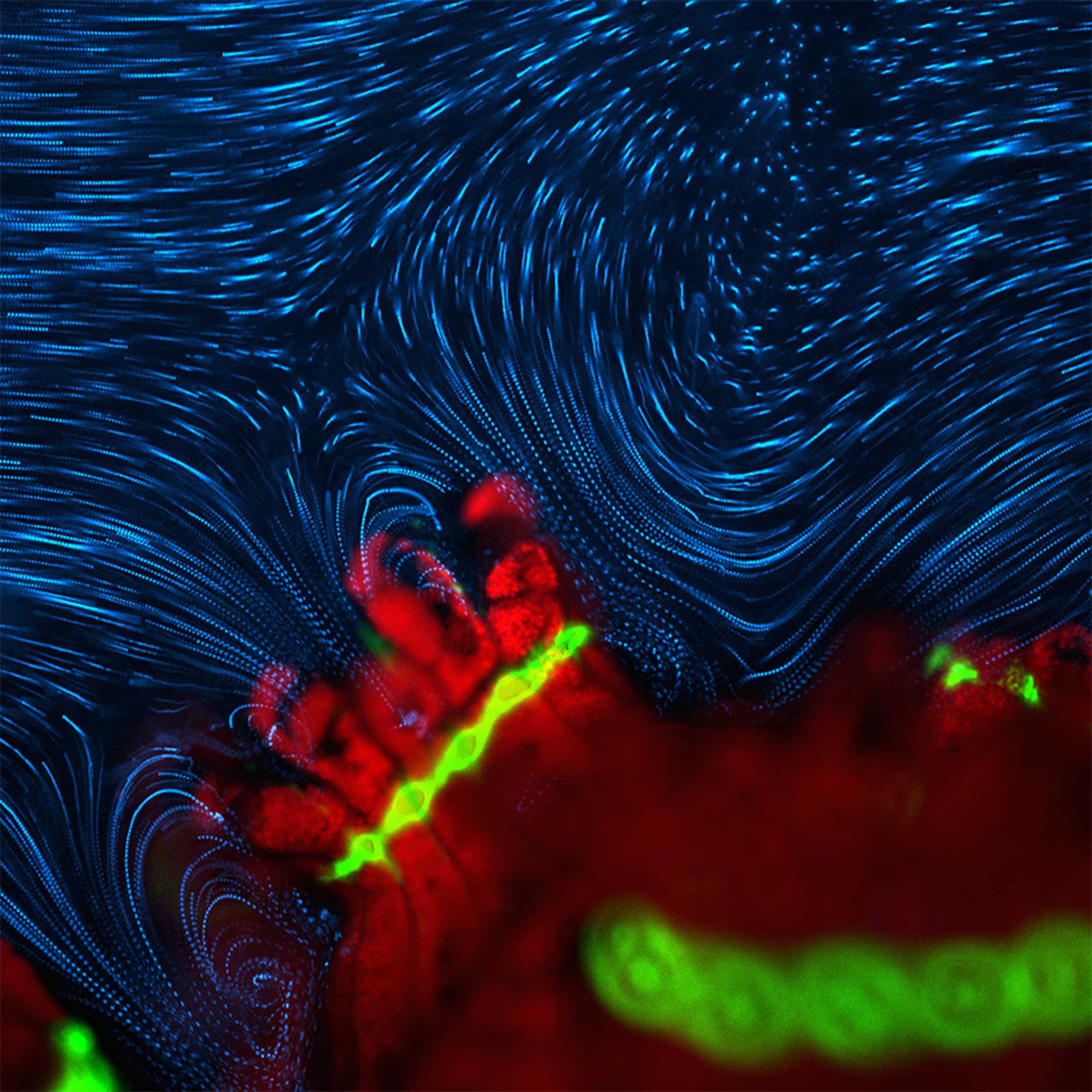

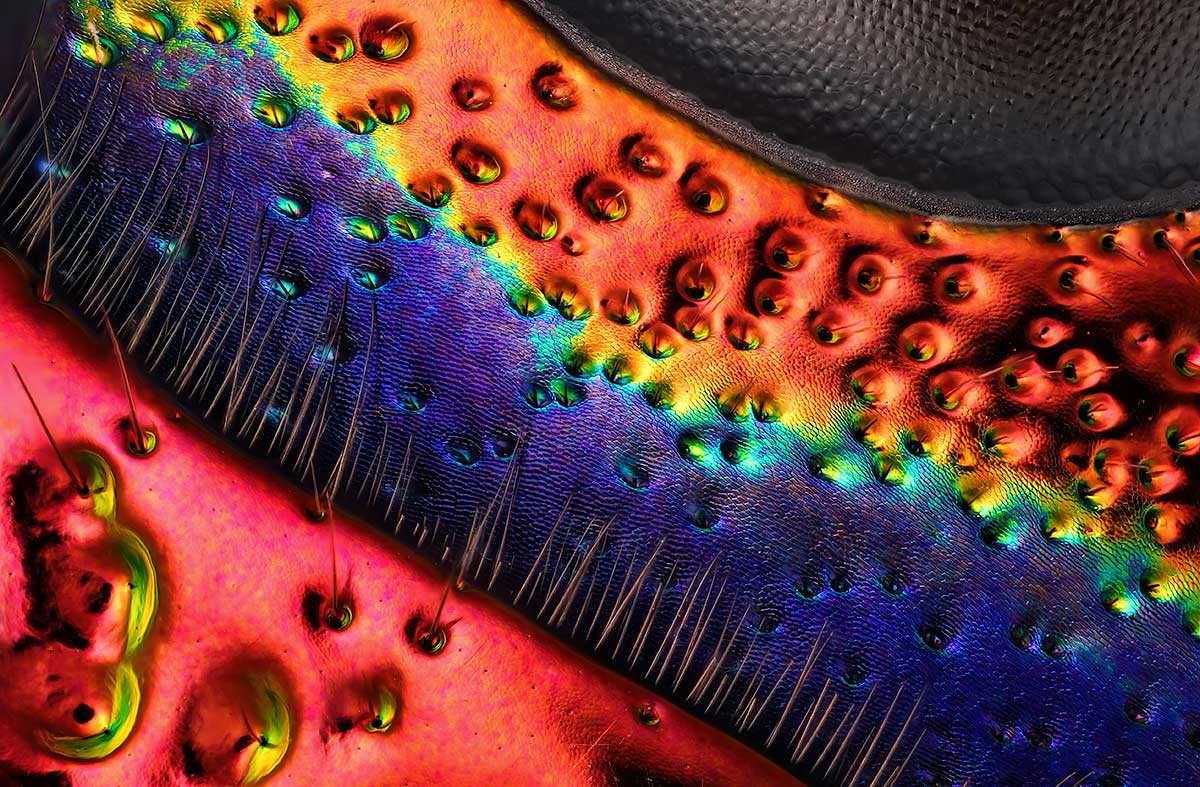

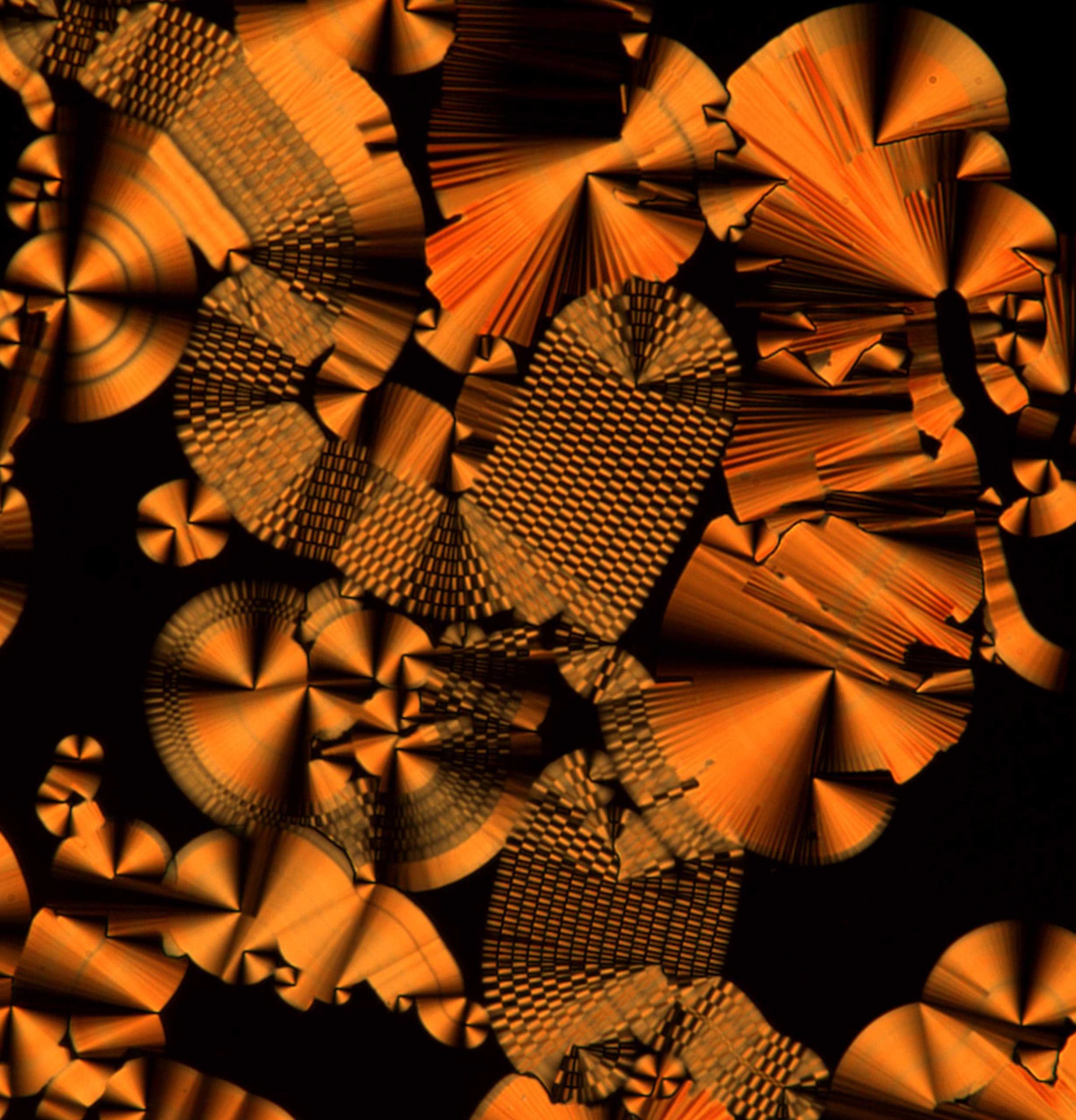

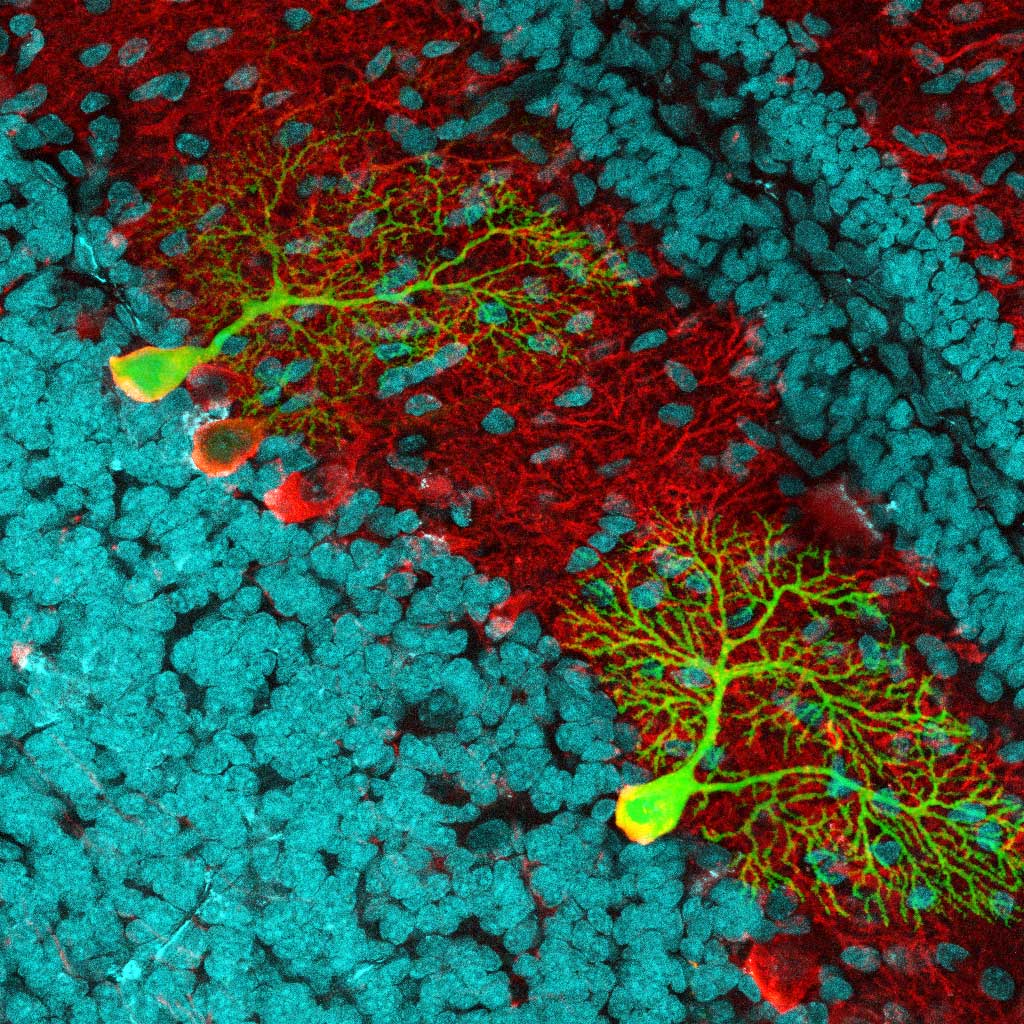

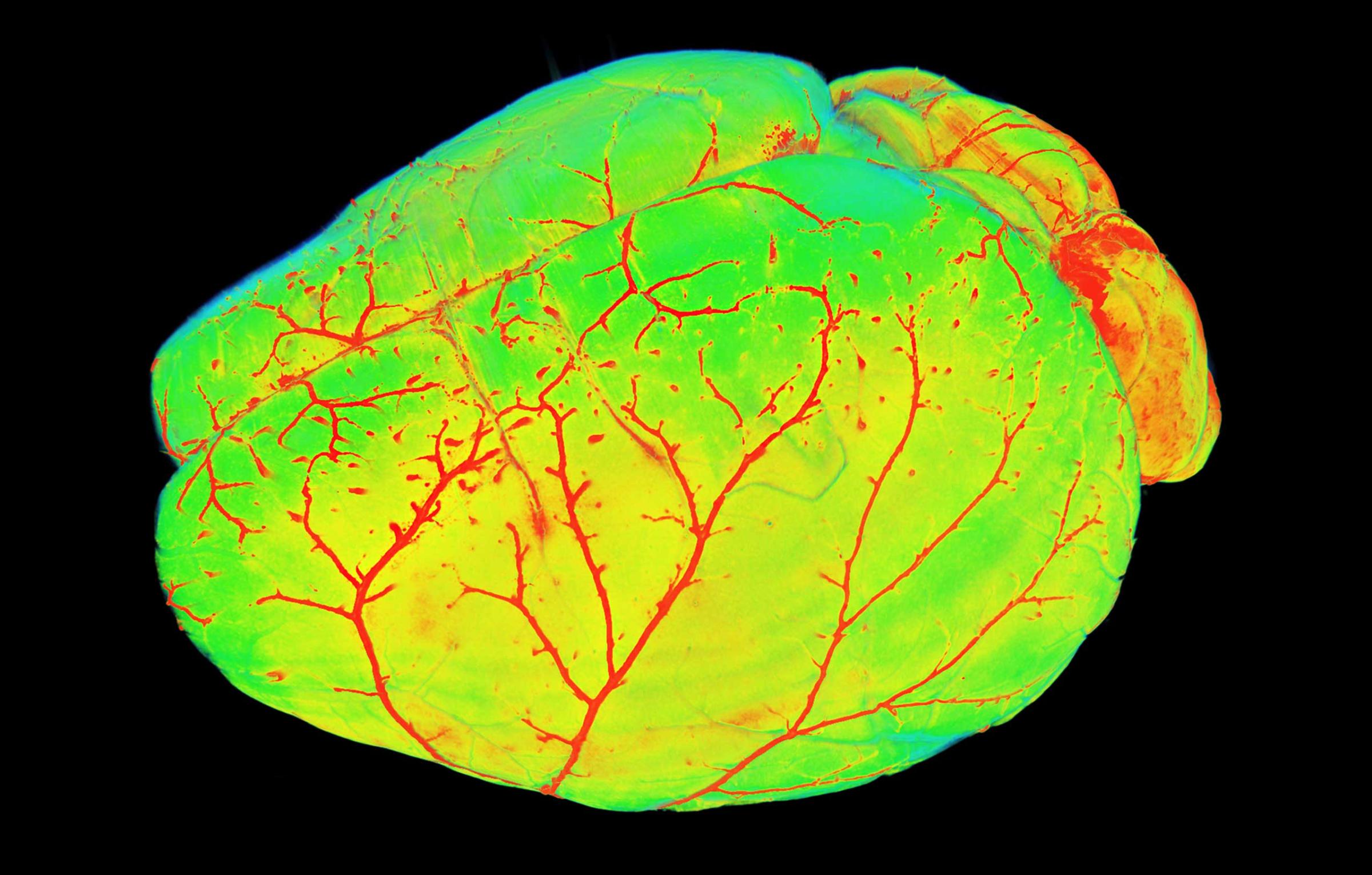

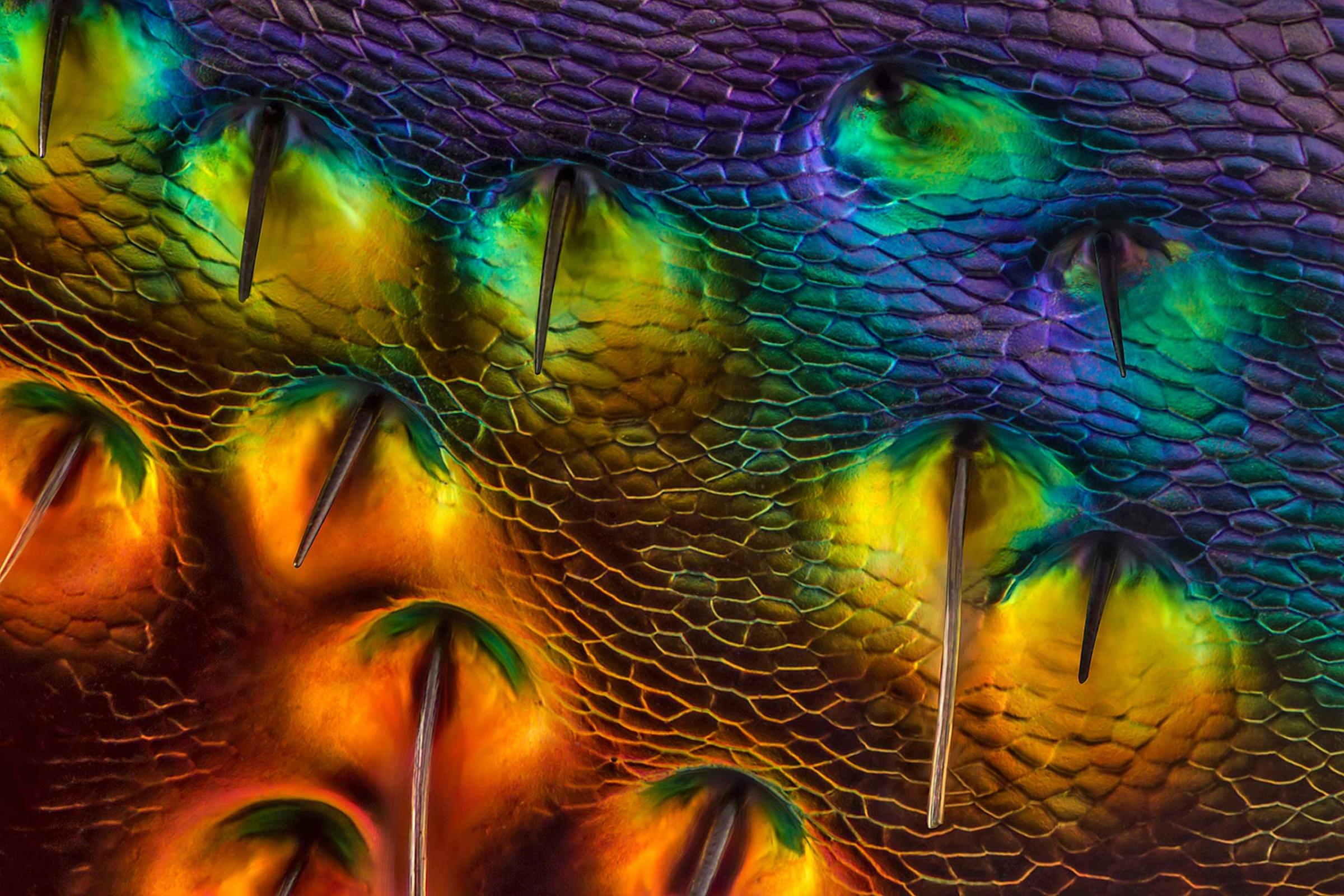

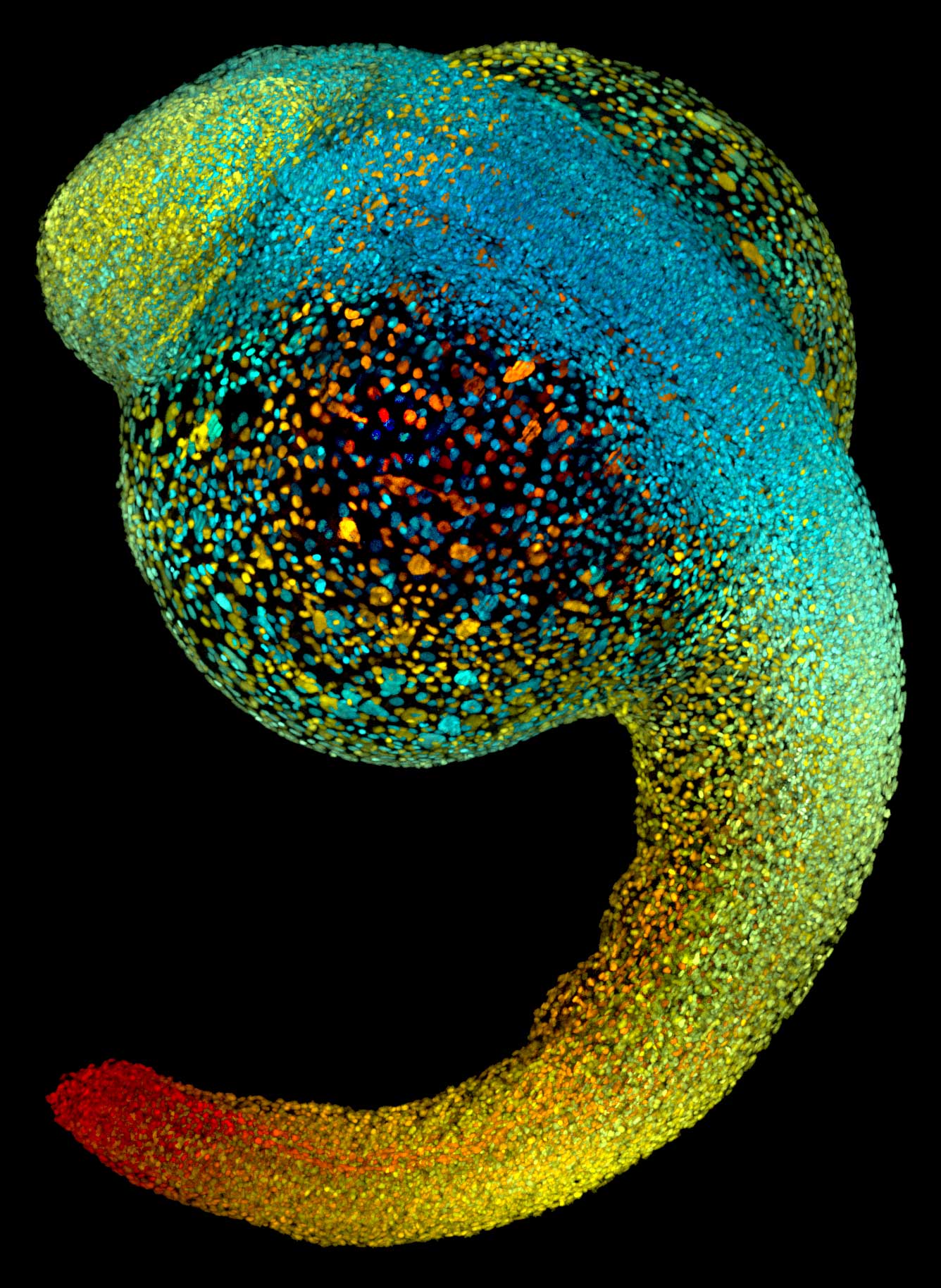

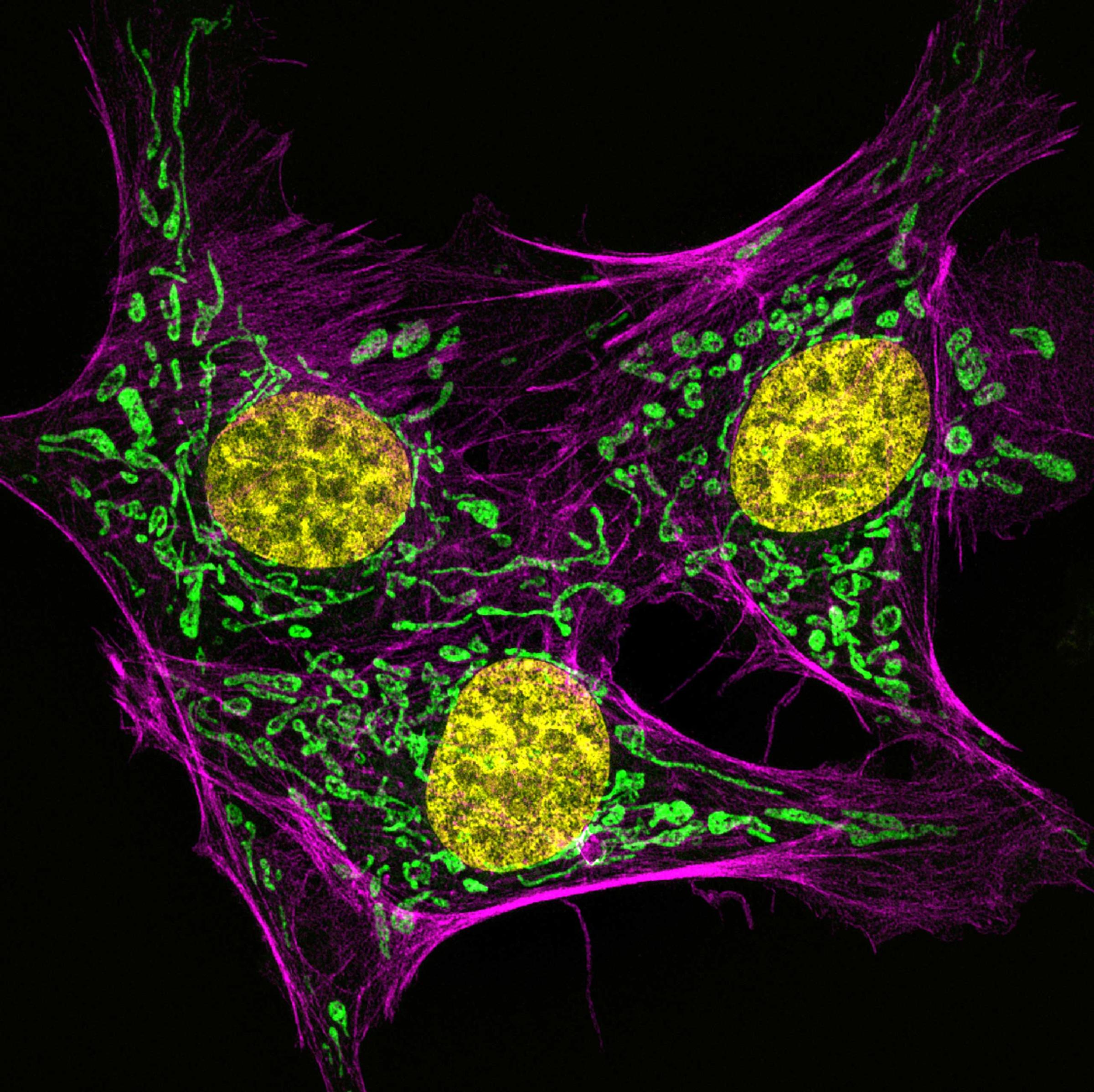

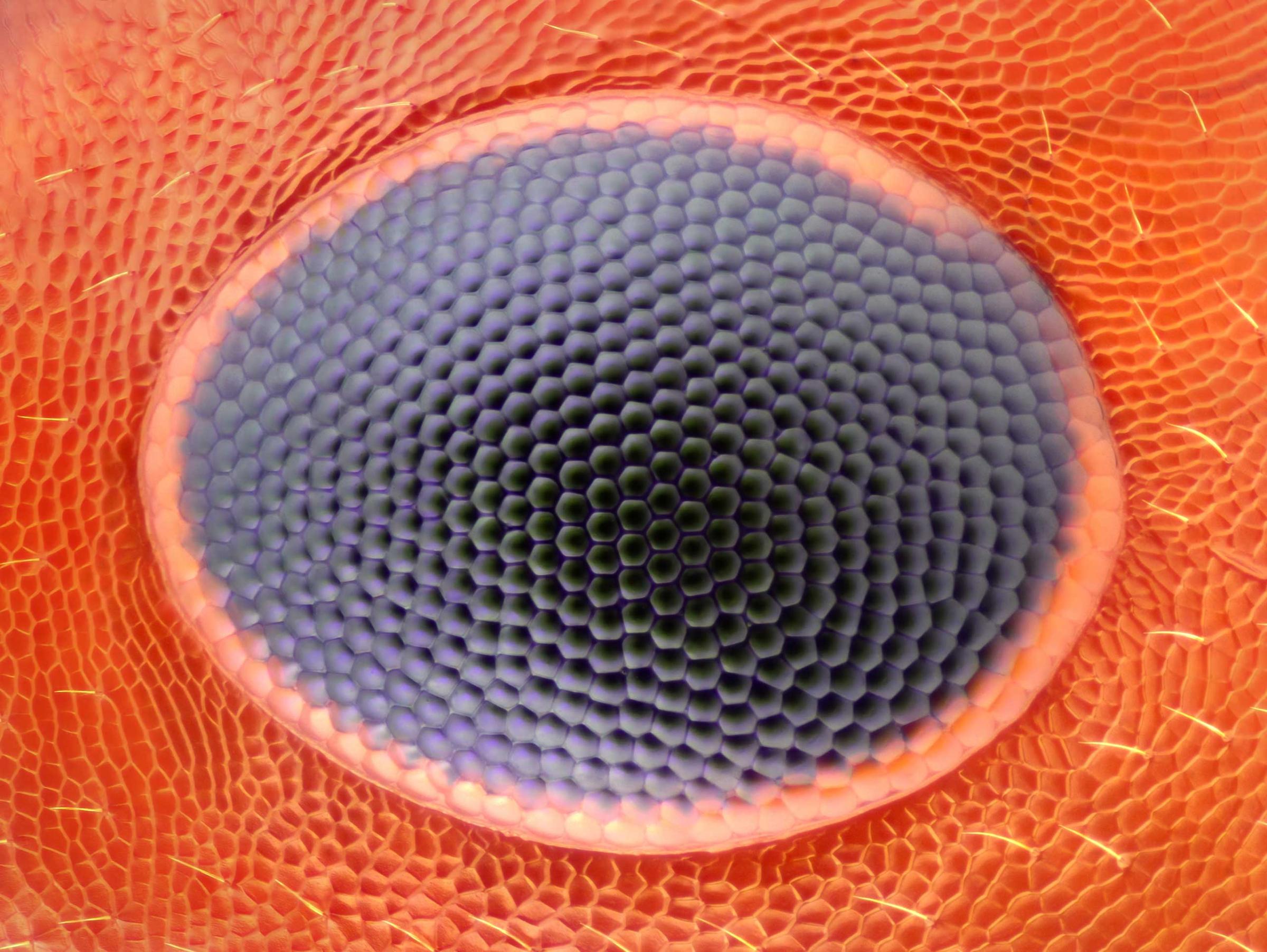

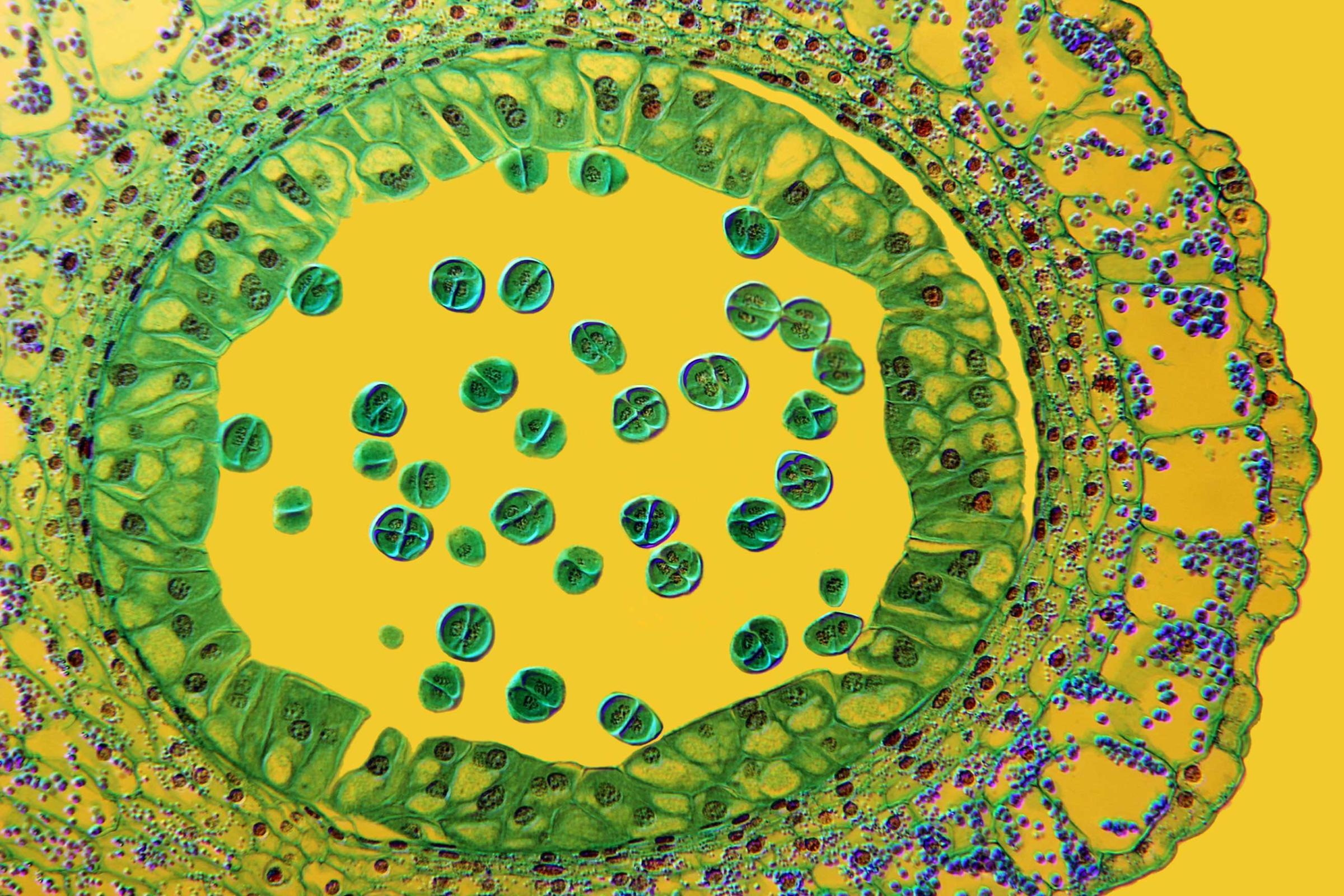

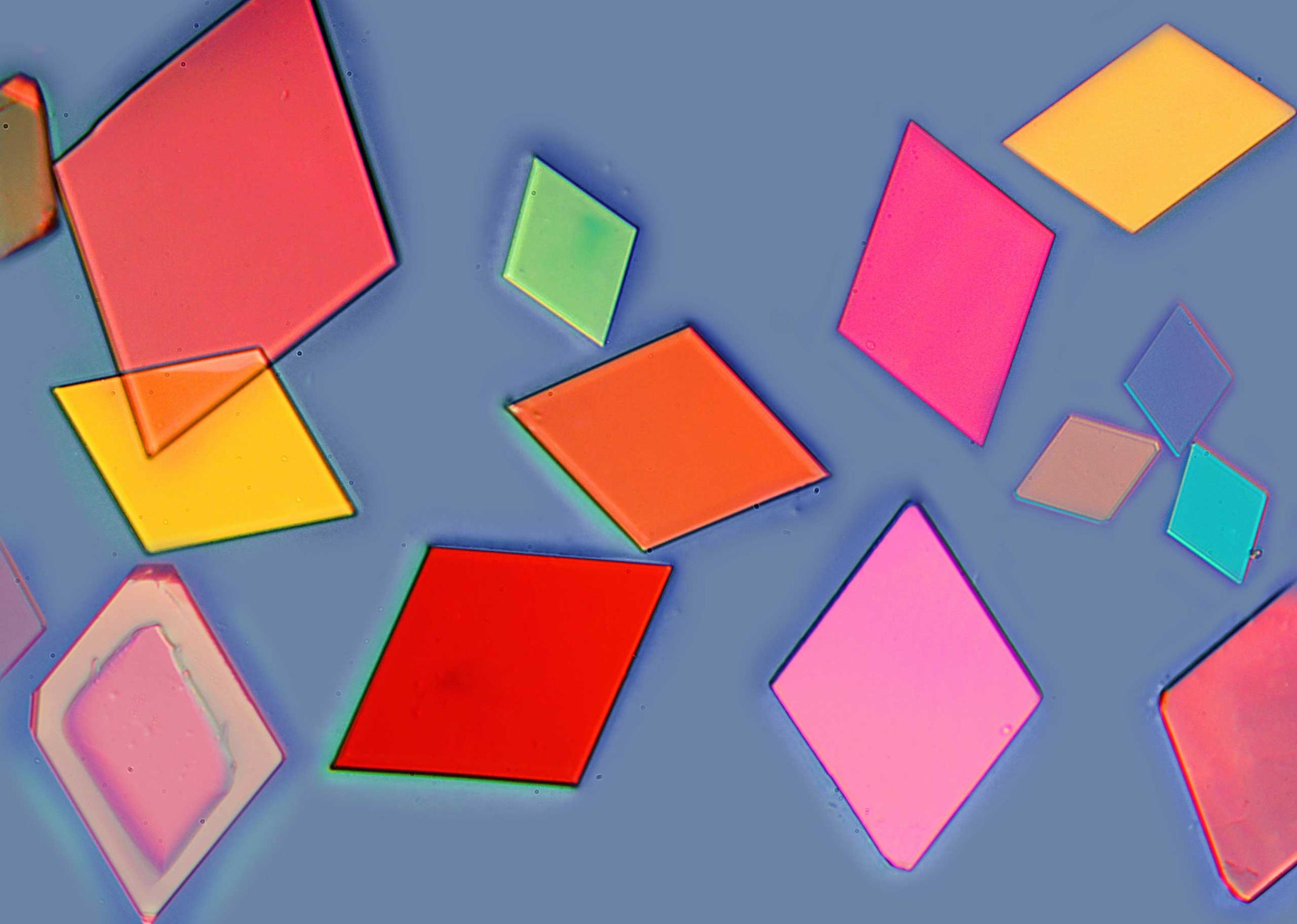

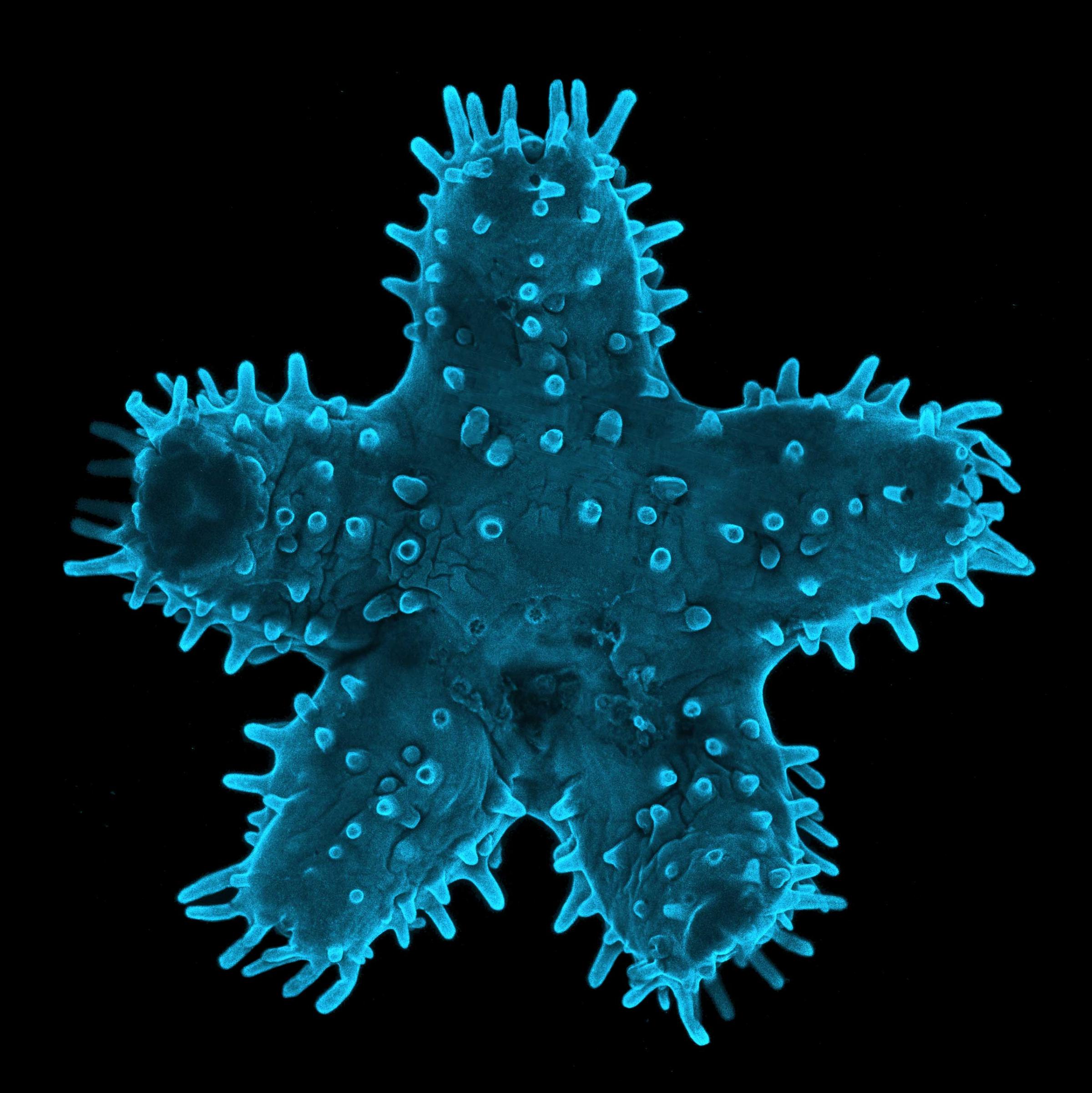

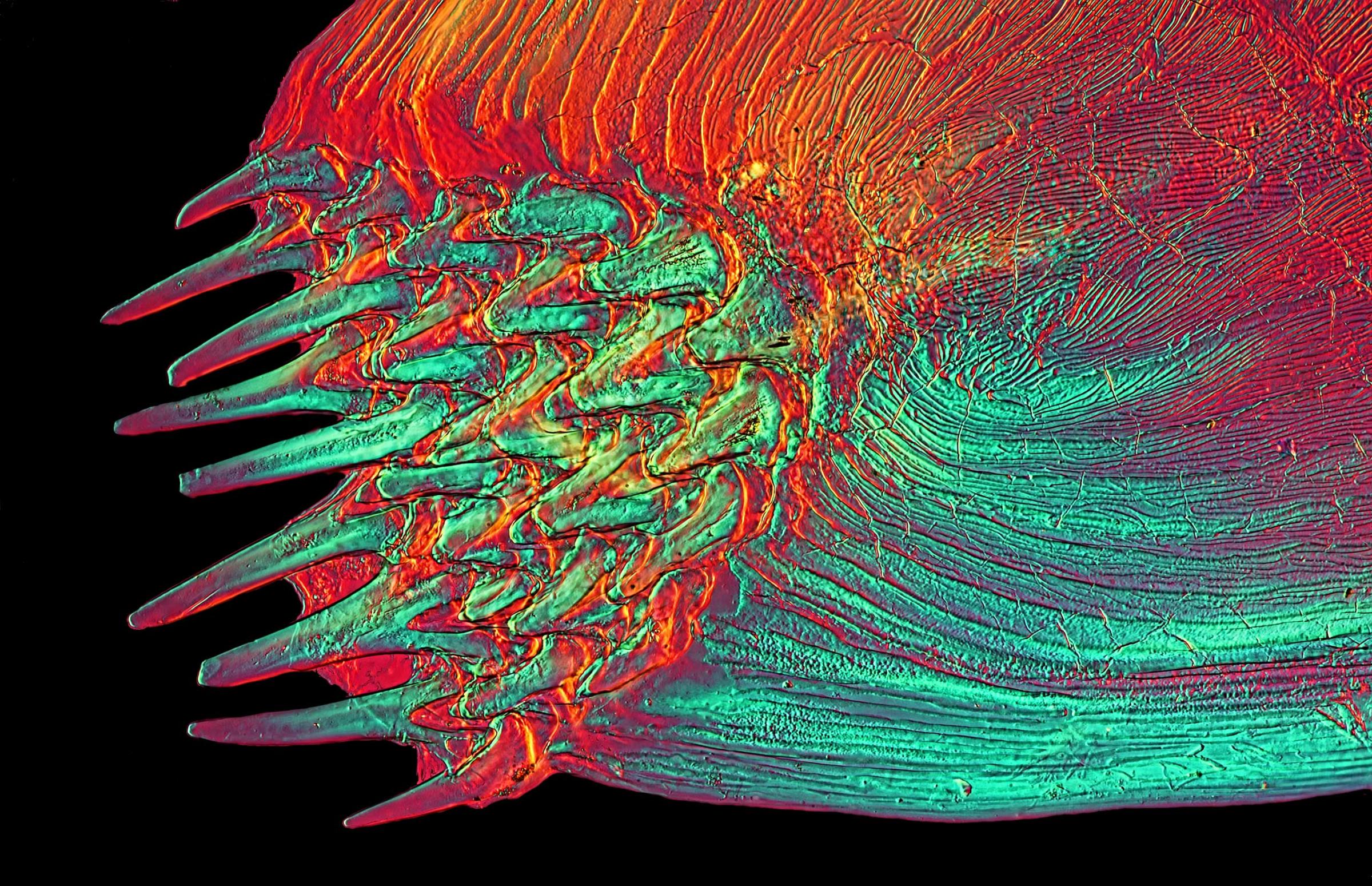

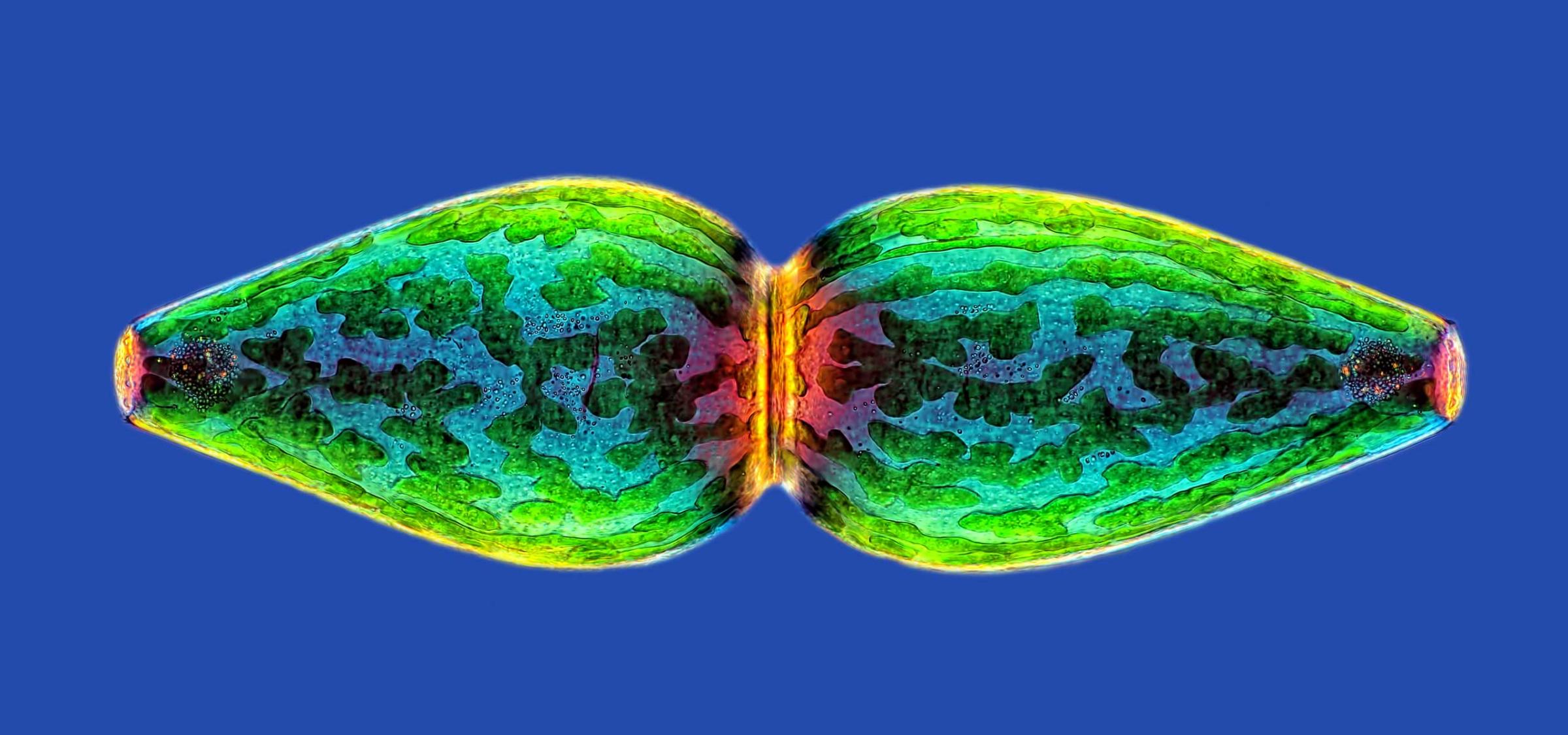

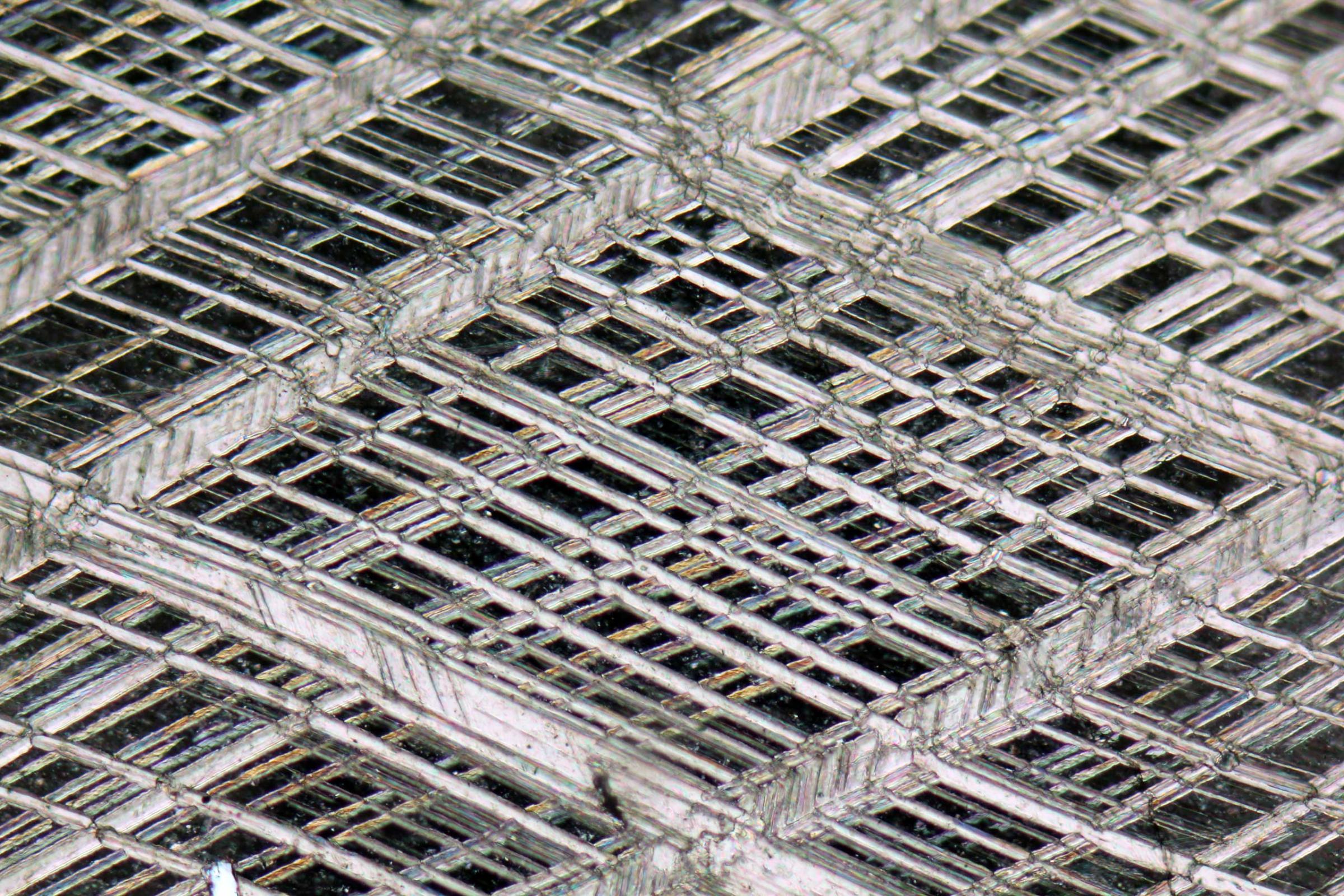

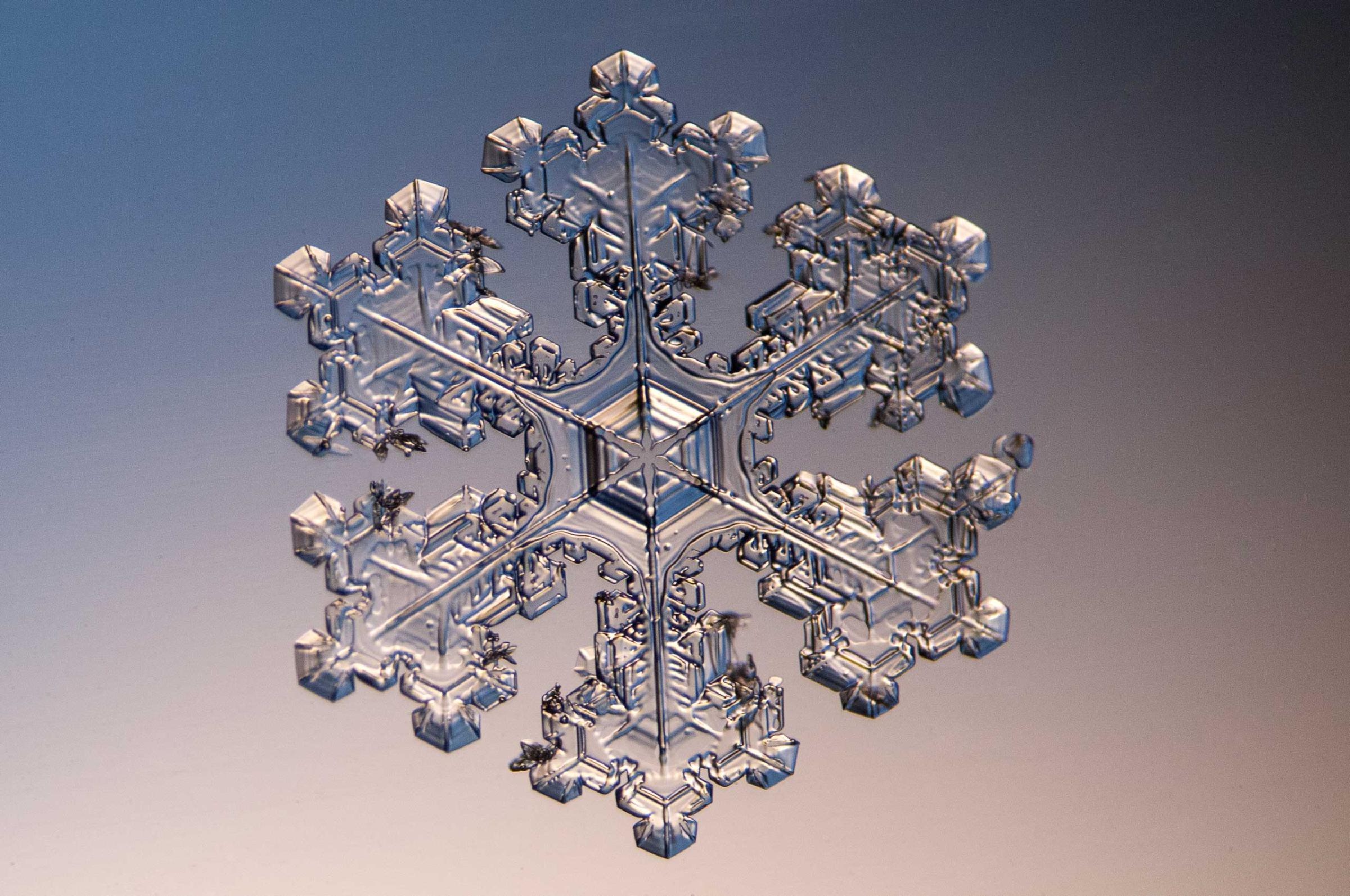

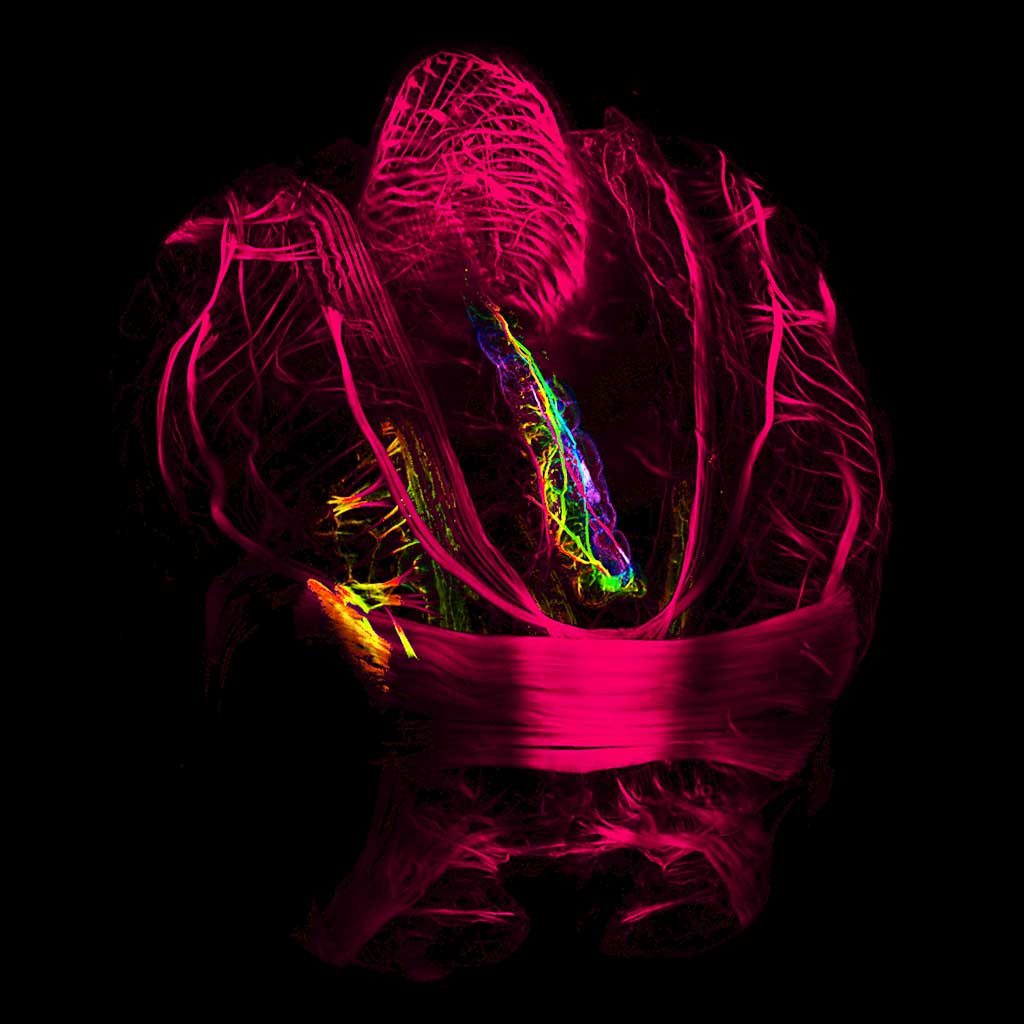

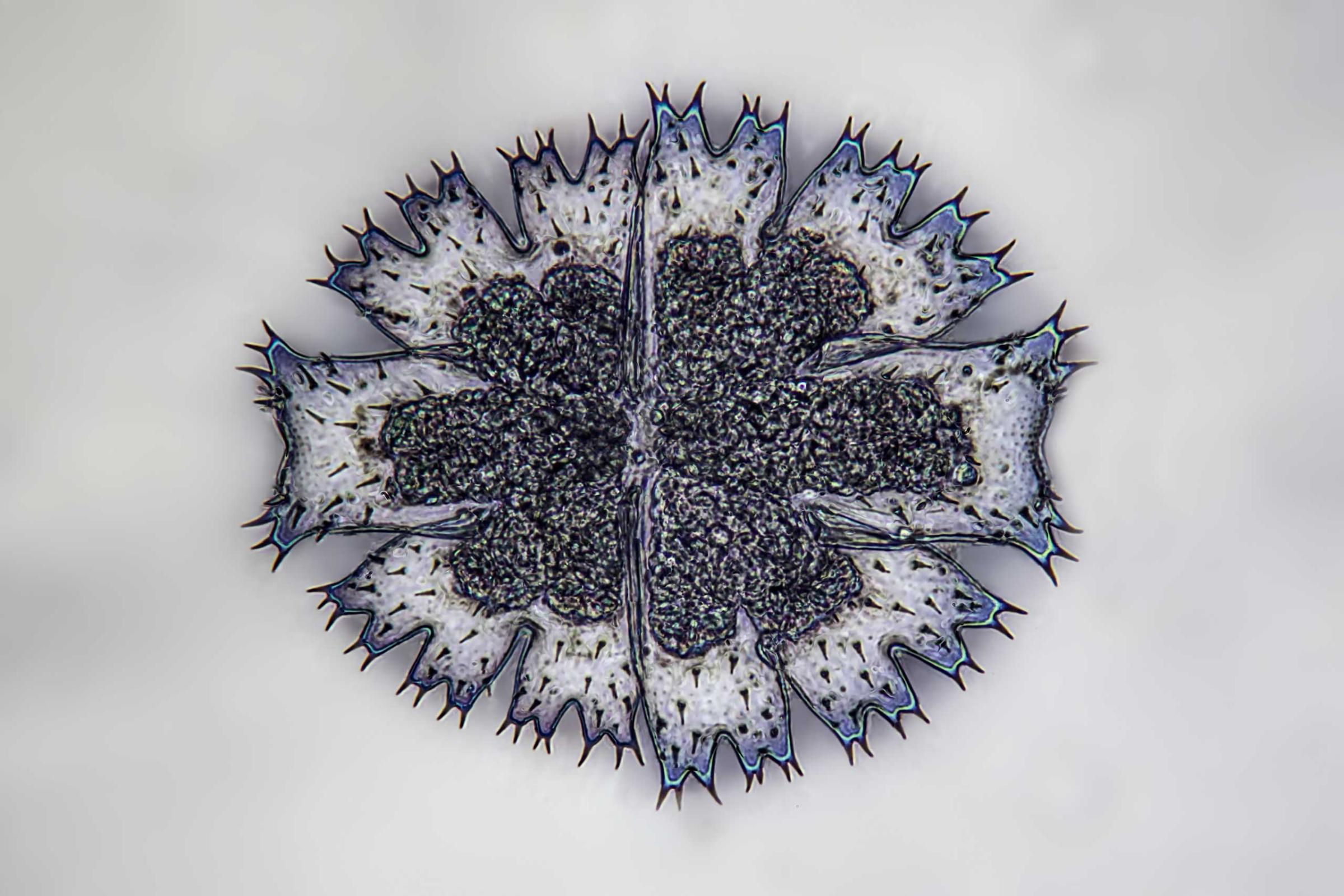

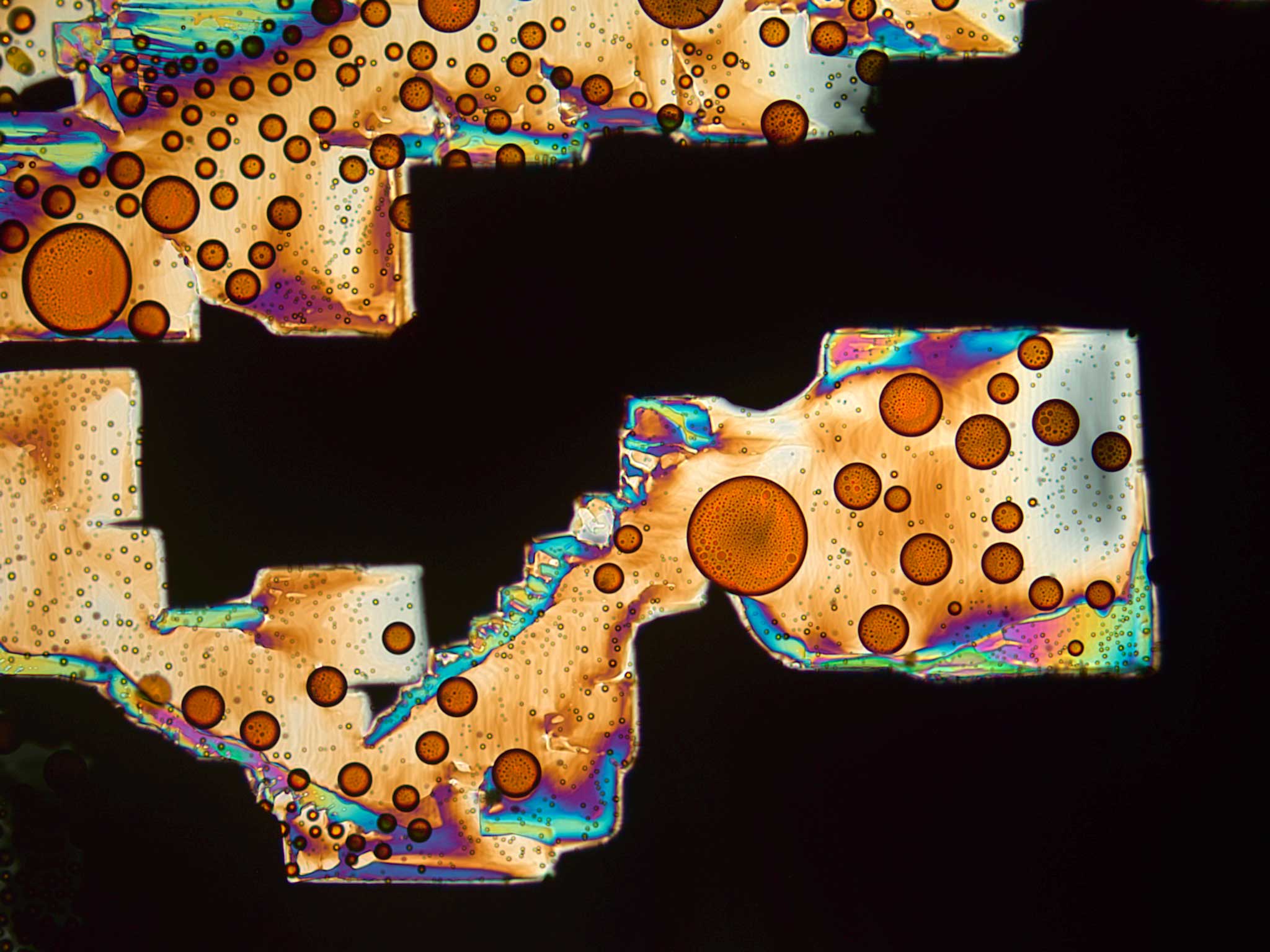

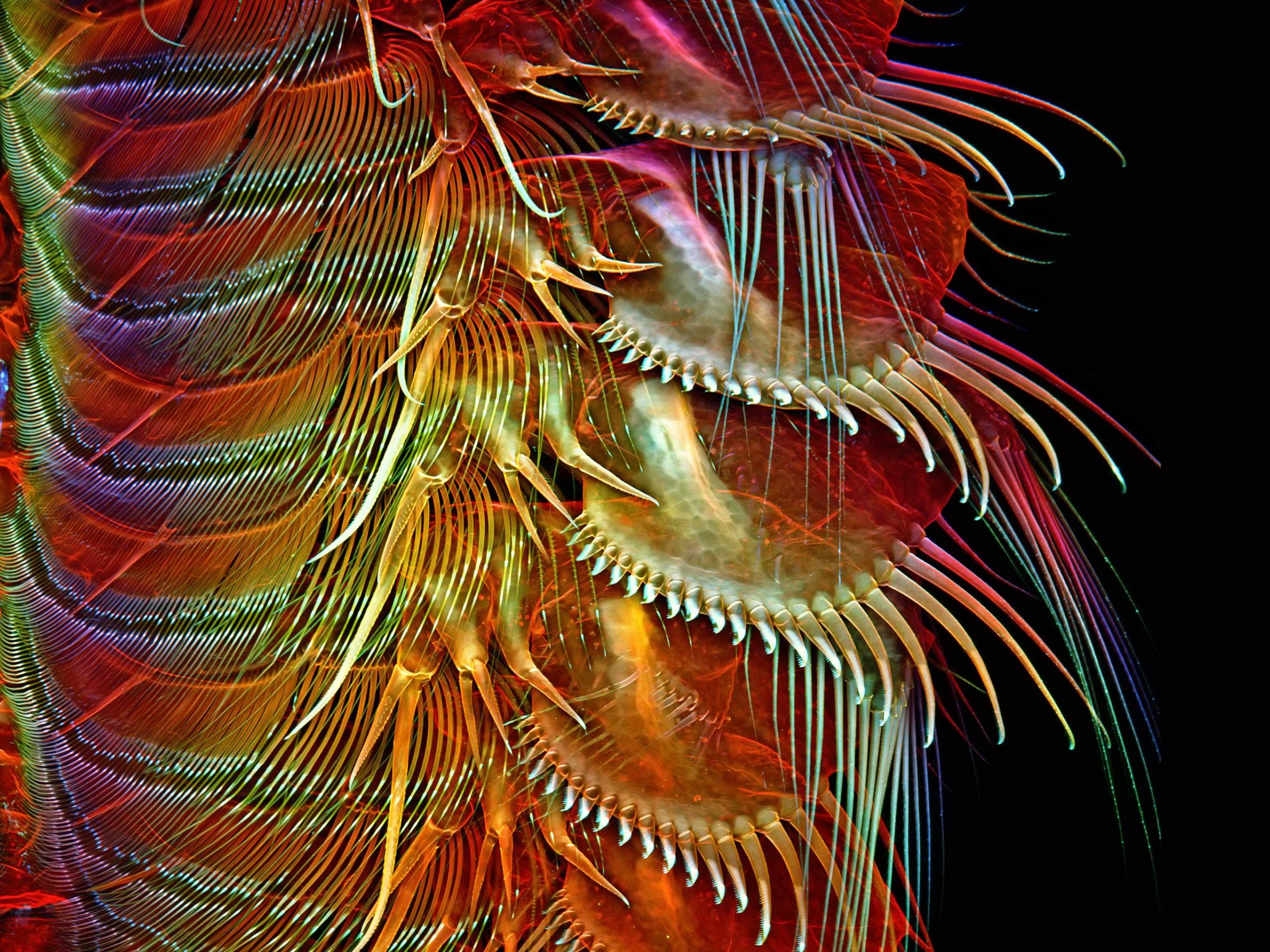

See 40 Stunning Images Captured Through A Microscope

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com