It’s not news that this year’s Super Bowl expects huge TV-viewership numbers: in fact, as Forbes has reported, the increasing price of commercial space during the game means that a whopping 120 million people will need to watch — that’s nearly 8 million more than last year — in order for those ads to be as valuable as they were last year.

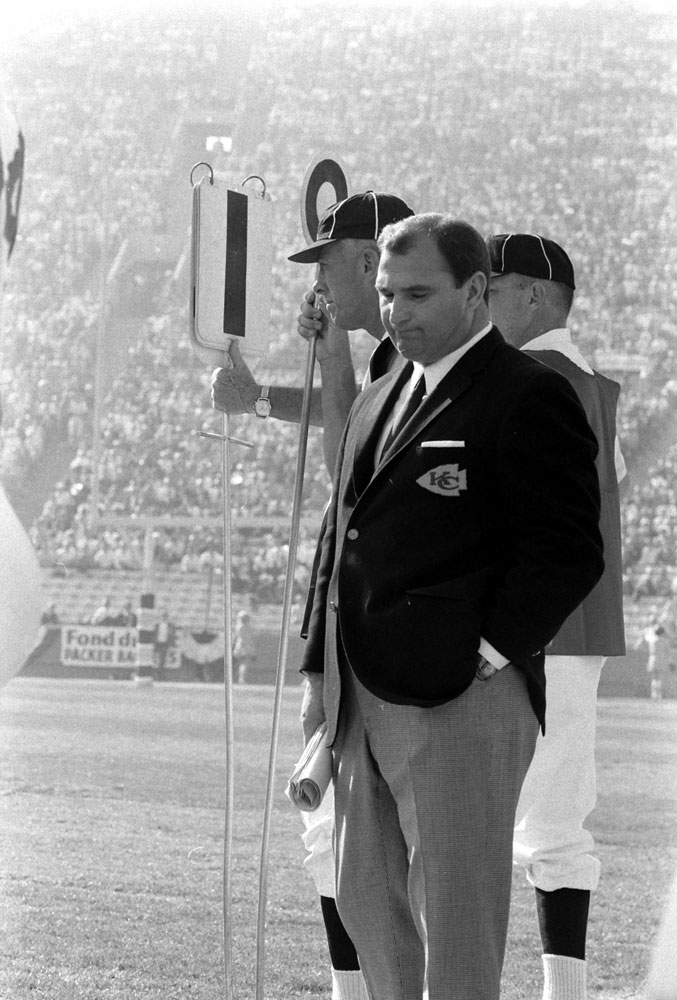

But, when the first Super Bowl took place in 1967, football on TV was a very different beast.

As TIME explained in a 1972 consideration of the “television football freak,” early television broadcasts of football involved a camera held in position above the 50-yd. line and a commentator describing the action à la a radio broadcast, as if the picture weren’t also visible to TV viewers. By the time of the fifth Super Bowl, the production surrounding the TV broadcast had ballooned, including more than a dozen cameras and 100 crew members. Instant replay and jumbo screens within the stadium had also become a thing. The estimate for viewership that year, in the days leading up to the game, was around 62 million.

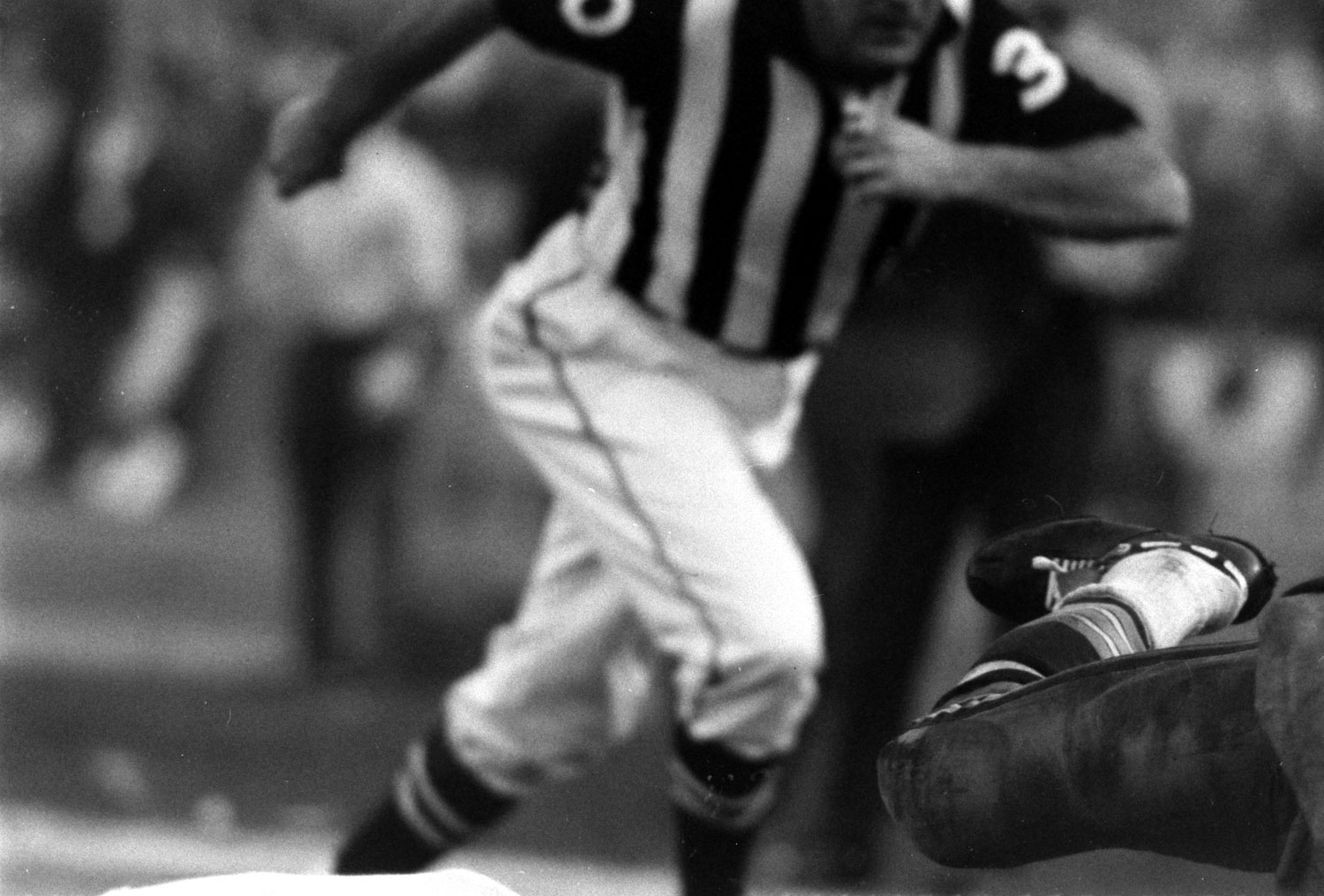

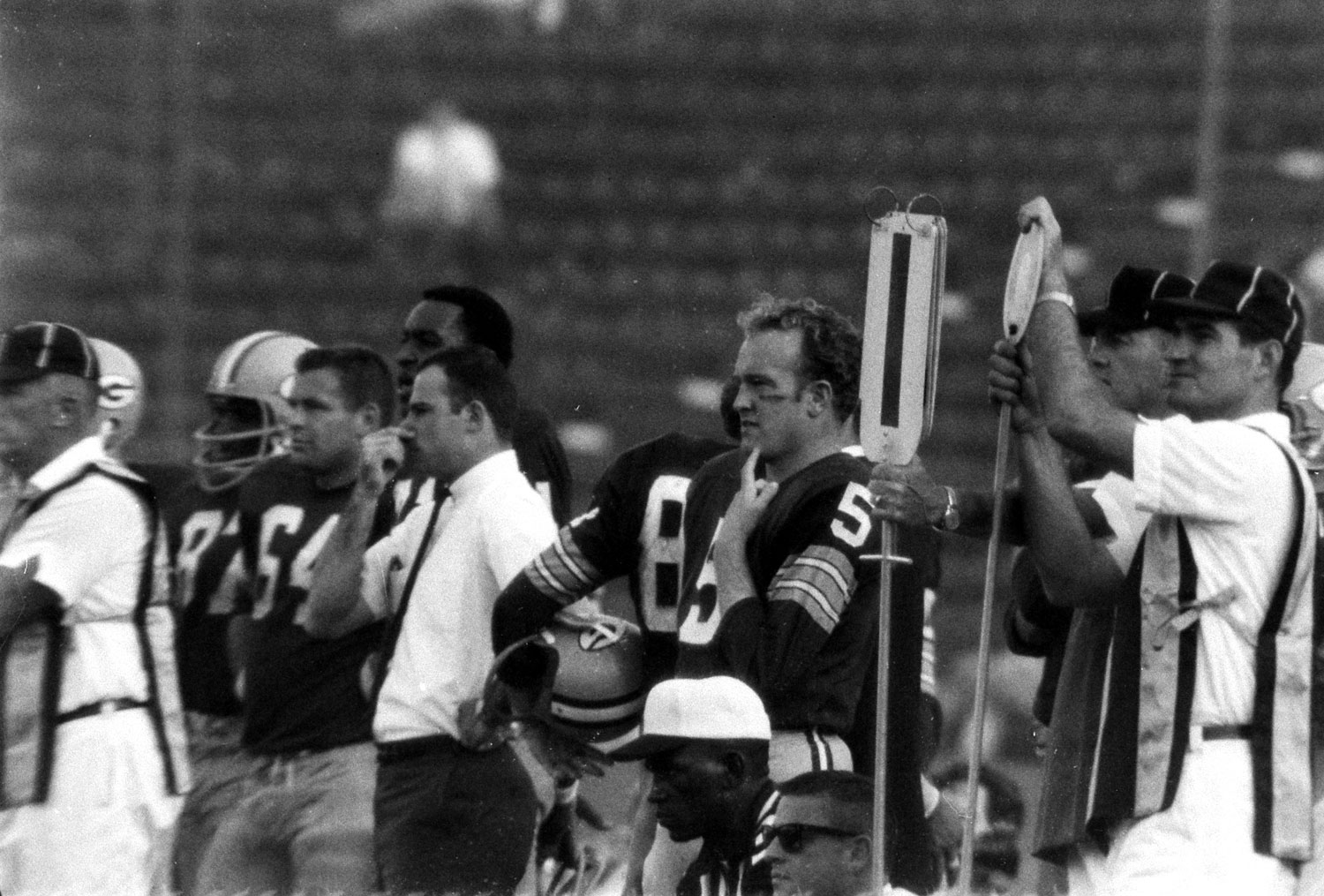

Expanding the TV coverage of football wasn’t easy, for the same reason that playing football’s not easy. Once the single, stationary camera was replaced by an array of moving cameras, that meant that the cameramen and TV directors had to be able to guess where the ball was going to go. When they guessed wrong, the viewers at home missed the play. (They could also miss plays for sillier TV reasons: TIME later remarked that the sport’s “first major concession to TV” happened in 1967, when the second half of the game had to have two kickoffs because NBC had been airing a commercial during the first one.)

As the expertise of TV sports broadcasters increased, so did interest in football. As TIME observed in 1973, that interest-at-a-distance, helped along by shiny commercial production quality, turned the spot from a mostly collegiate test of strength and character into a full-fledged entertainment behemoth:

Today, the beauty and fascination of the game are strictly in the beholder of the eye — the watcher of TV as it relentlessly patrols the field.

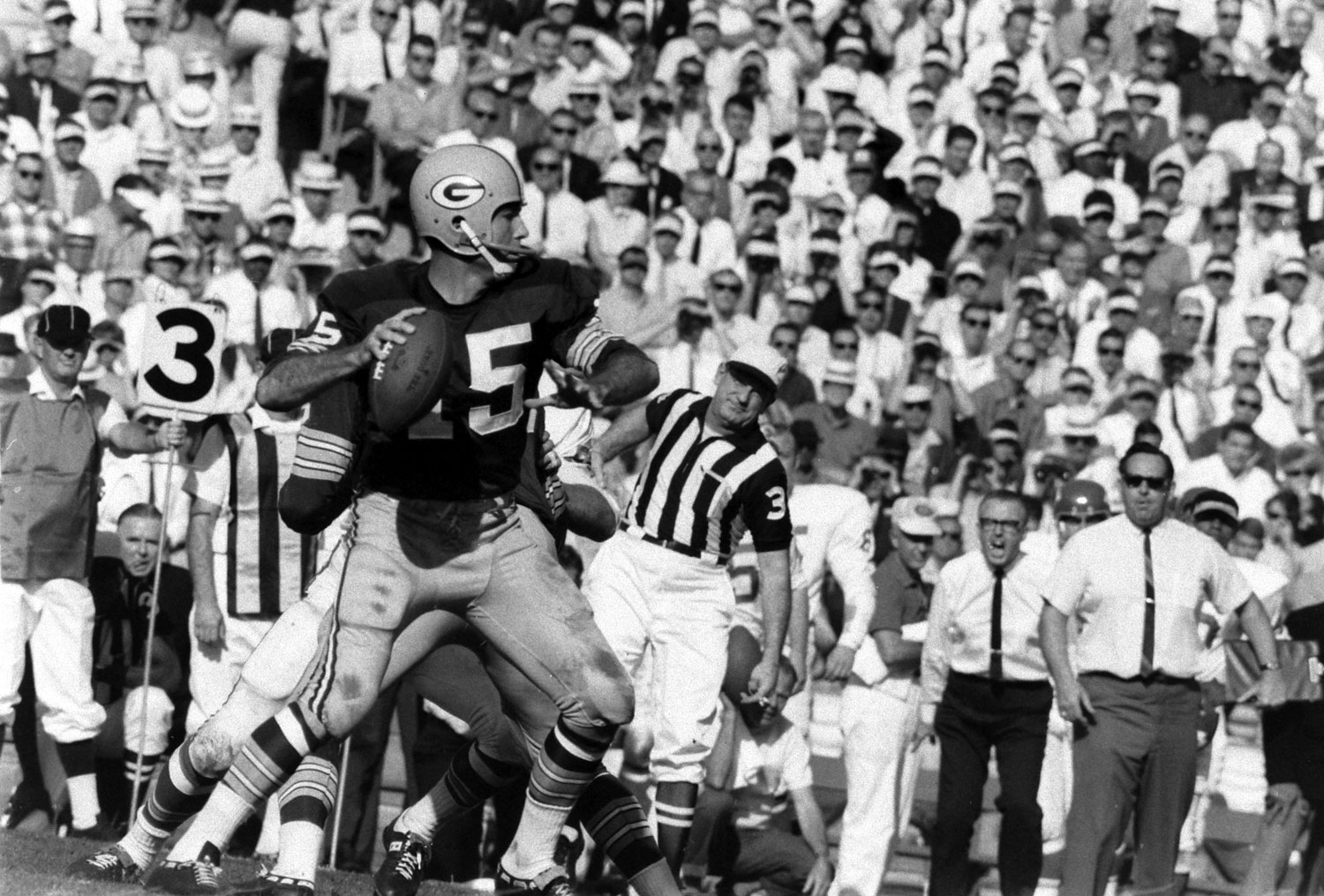

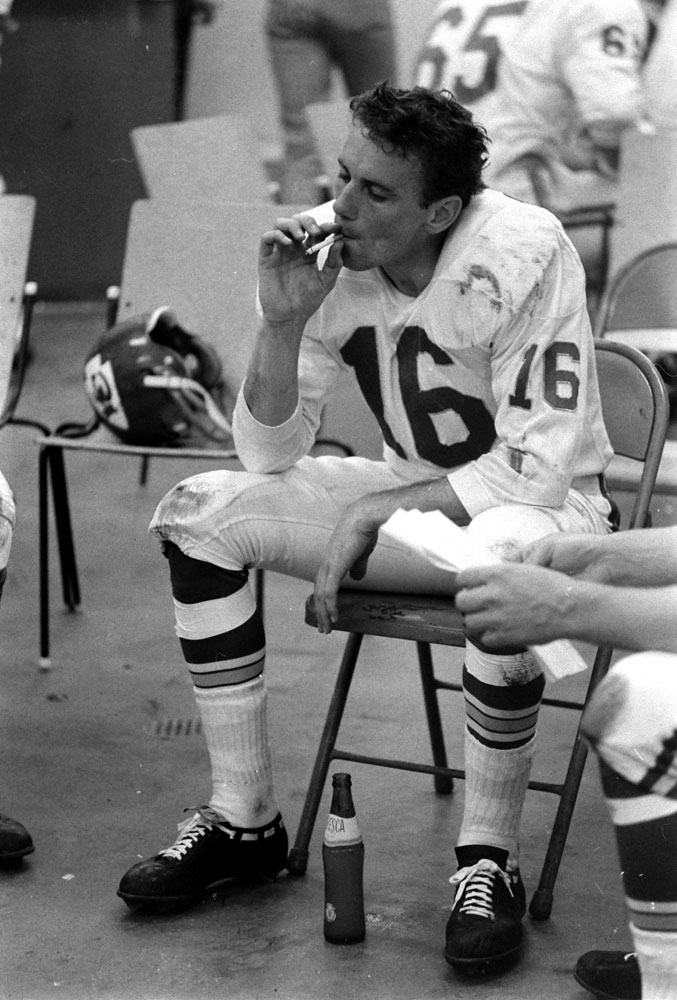

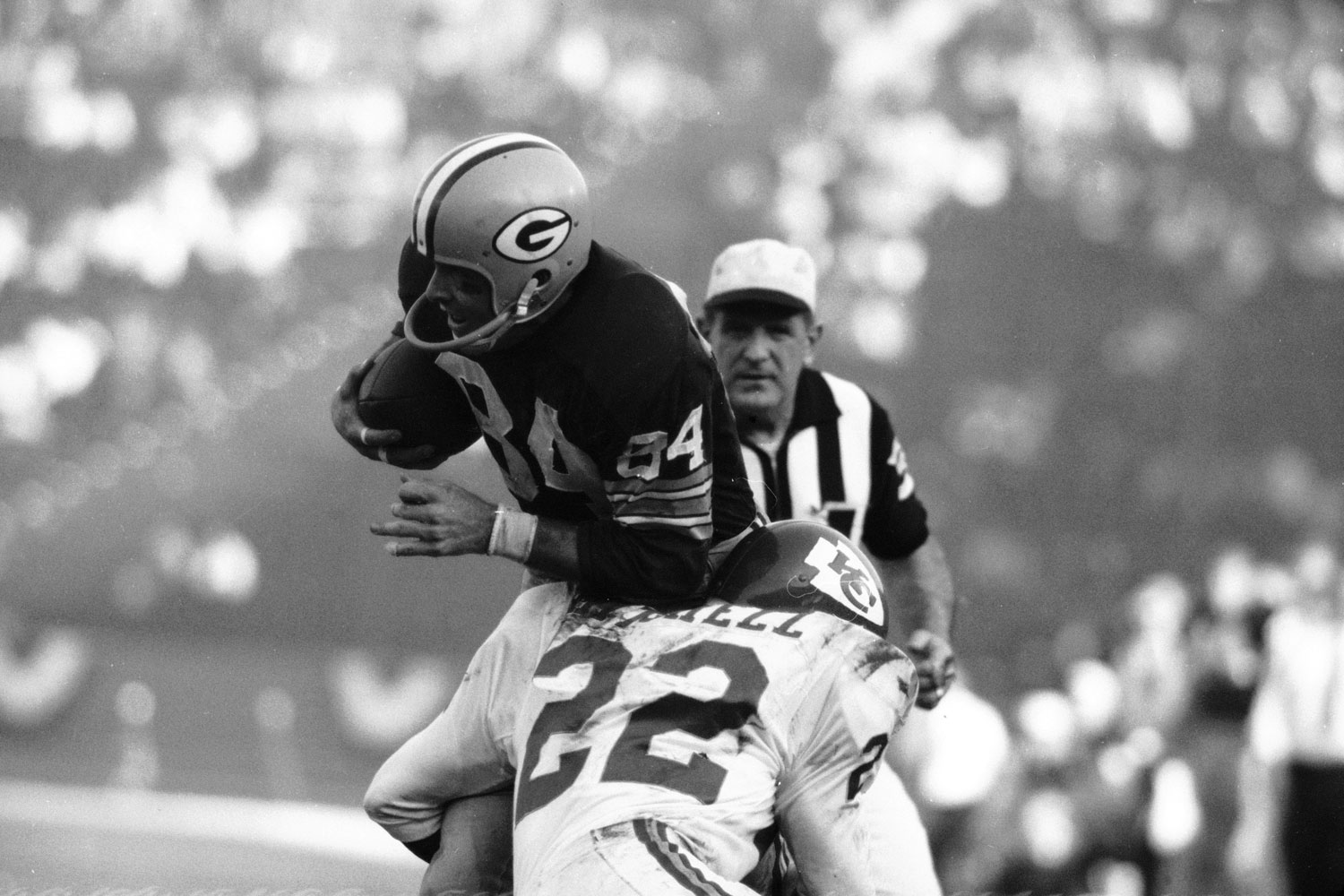

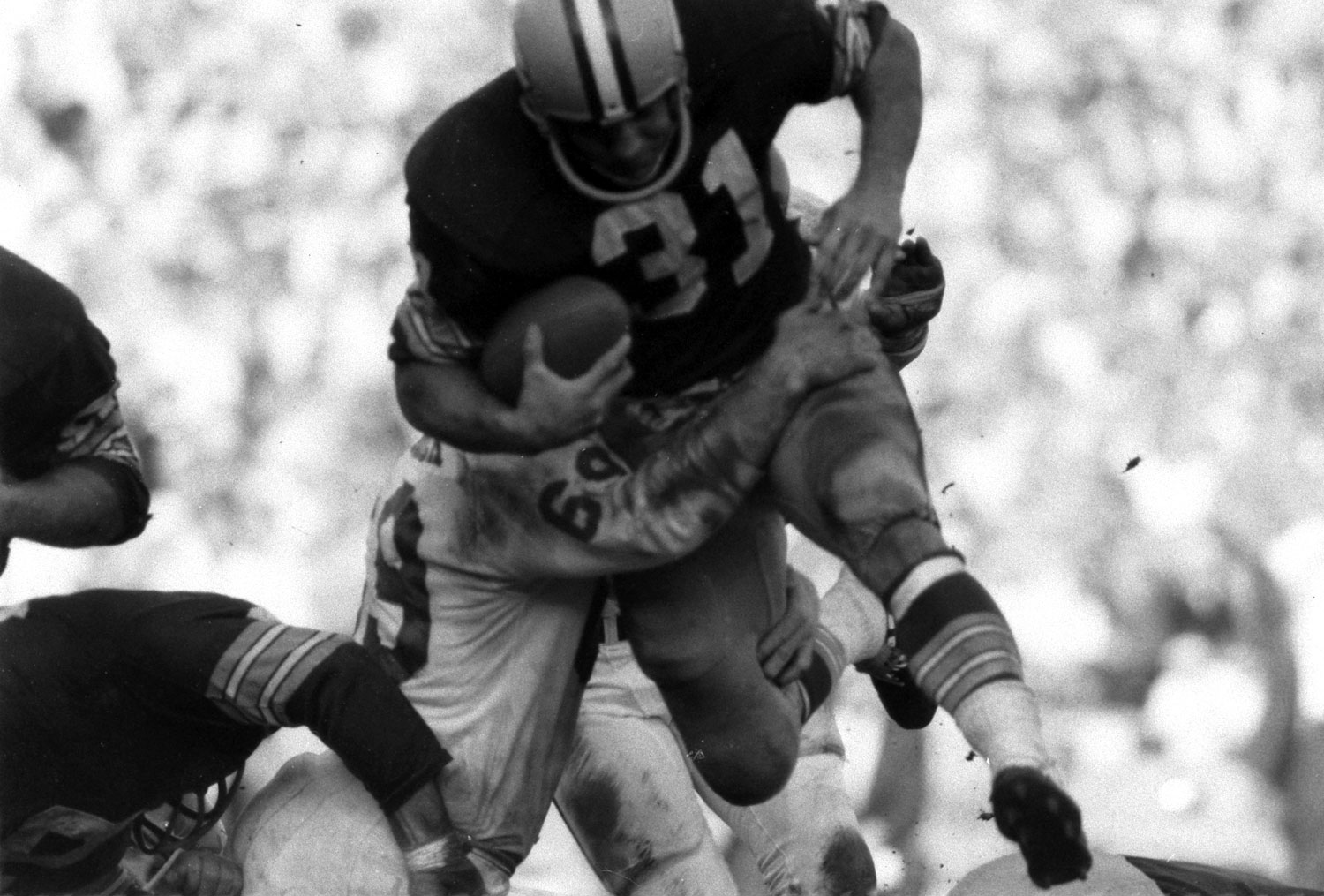

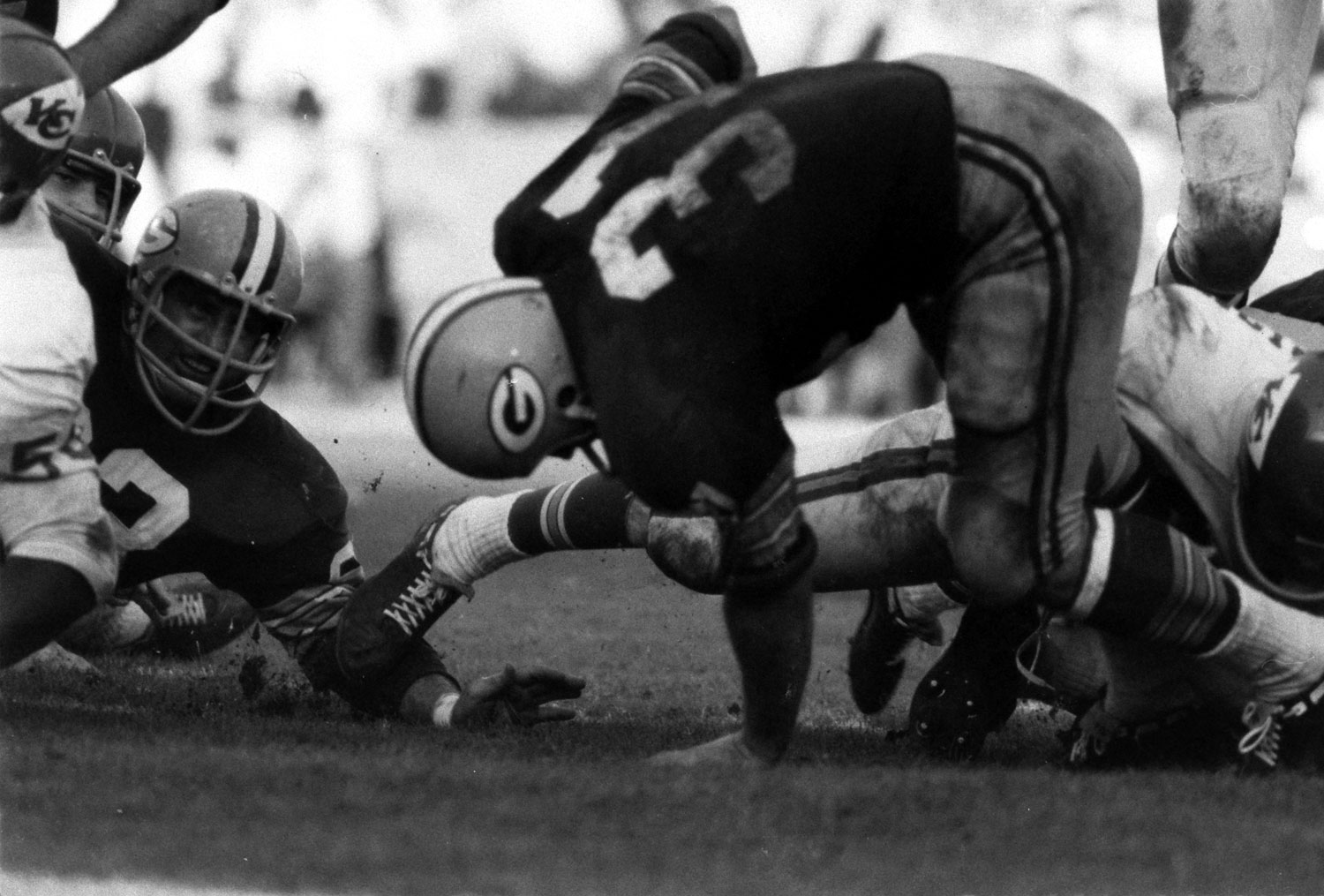

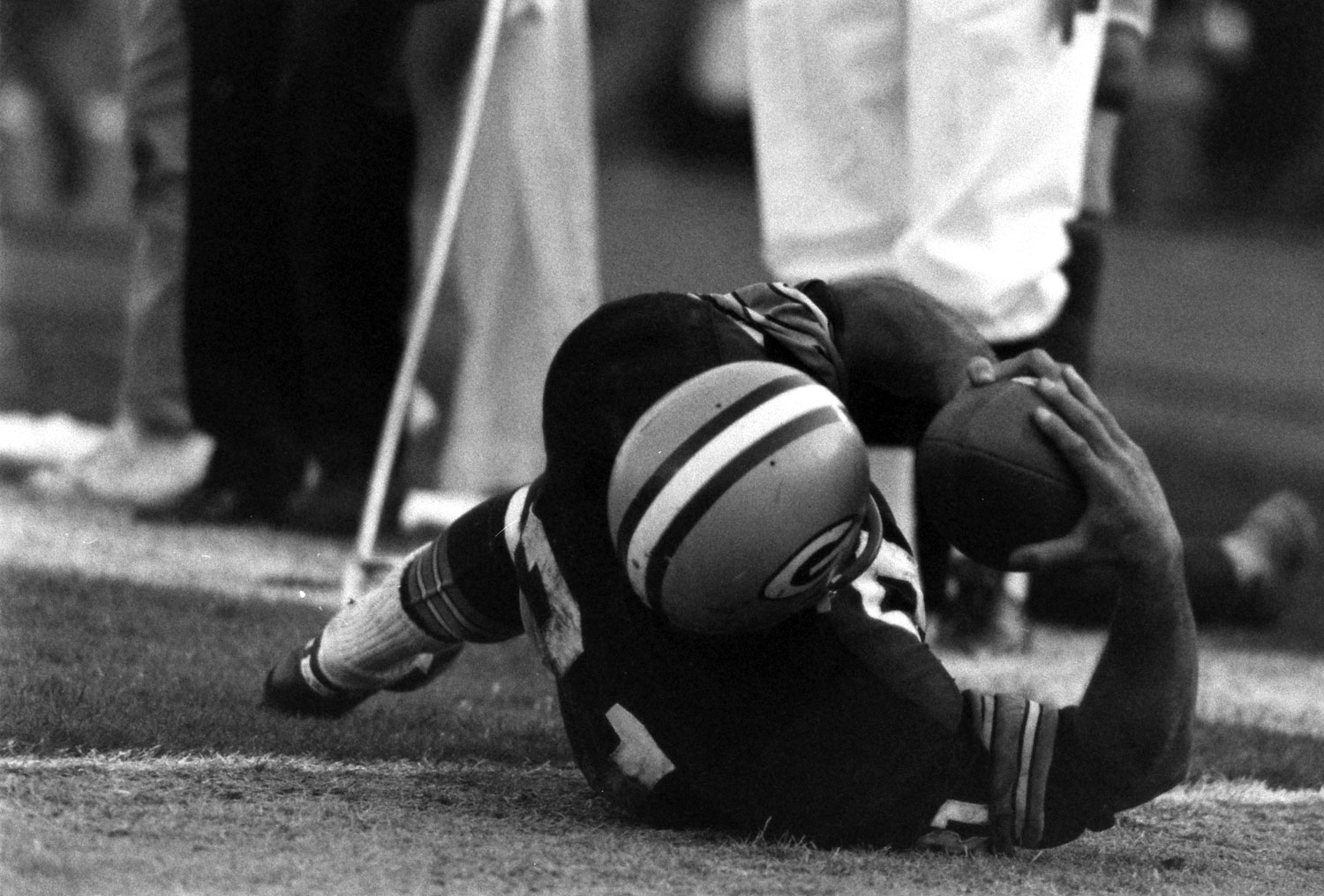

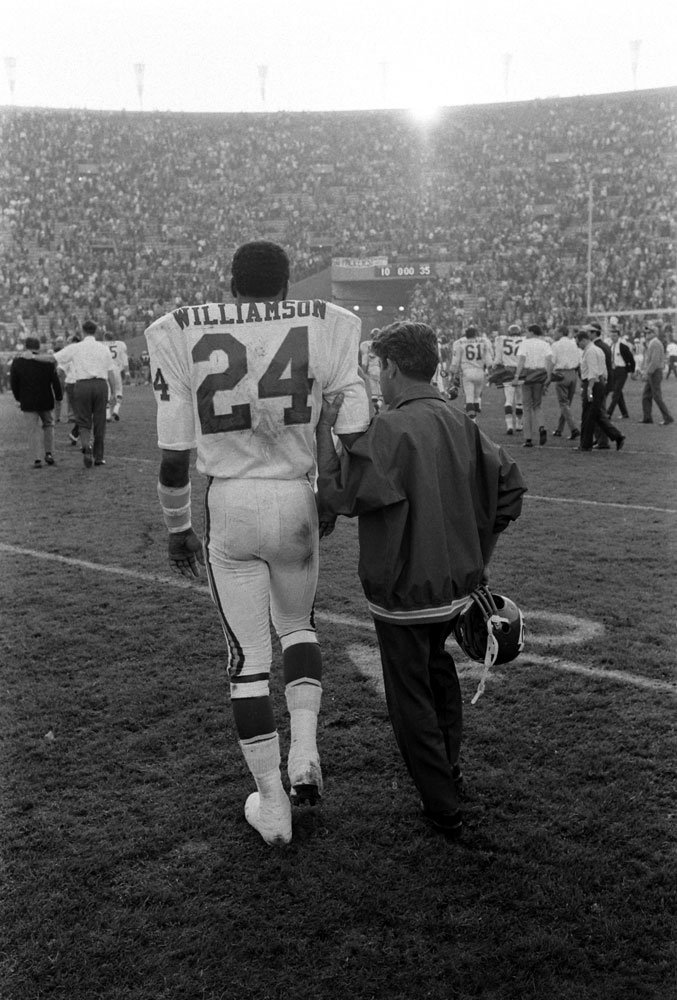

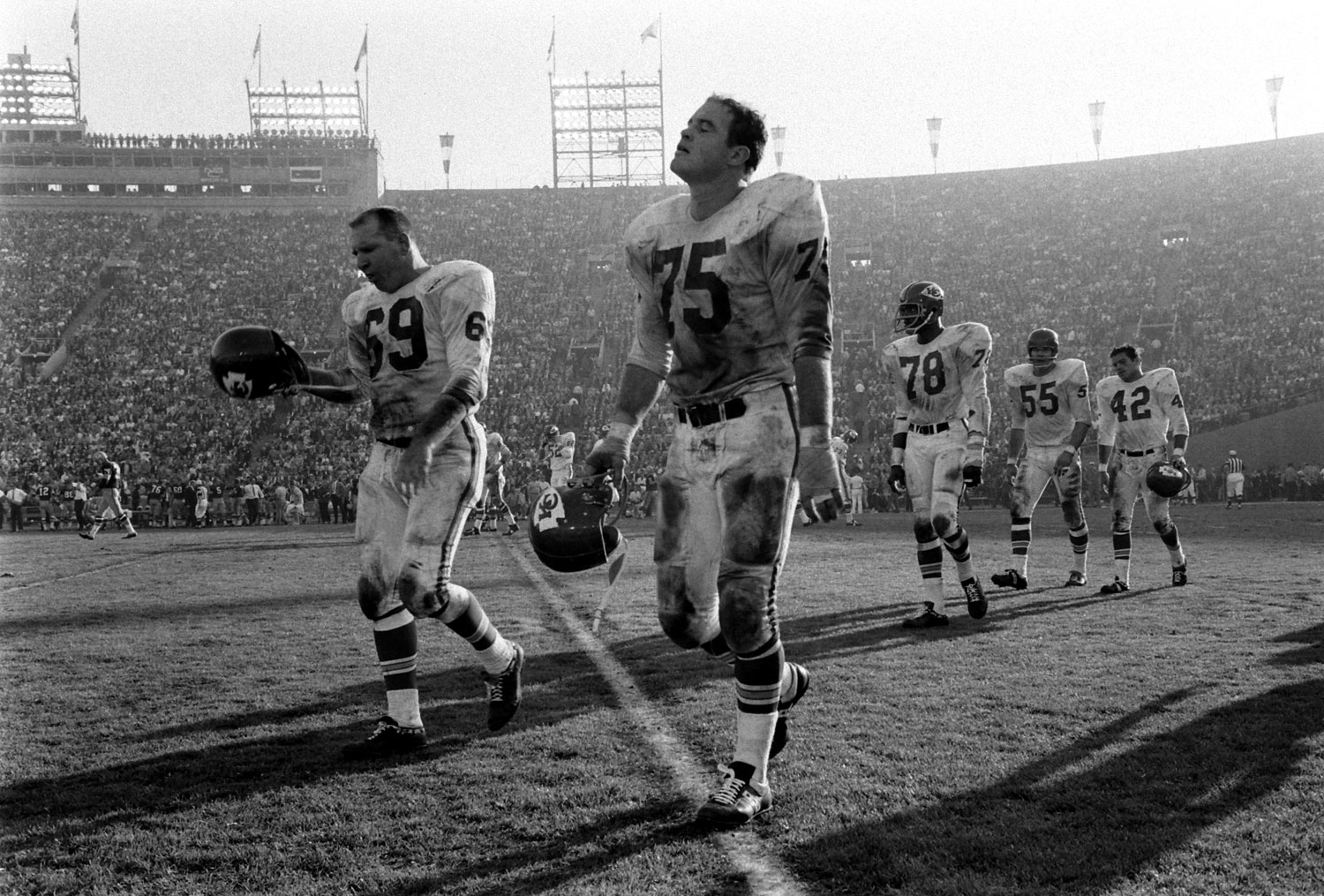

Without the camera, football would belong to the universities and the historians. With it, the game has become the most dependable branch of show business. Its cast of characters, its comedy and drama, are the envy of producers all over the world. At every performance, each player essays the impossible. He carries hundreds of detailed mental charts — yet contrives to move through 2,000 lbs. of enemies. He shows individual prowess — and attempts to mesh with the movements of ten other egomaniacs. He is battered, flattened, ridiculed — and still plays on, as much for the audience as for himself. (After all, who ends up paying for those $70,000-a-minute commercials — and those $100,000 bonuses?) In the process, the viewer receives a game of infinite hue and complexity, an amalgam of ballet, combat, chess and mugging. No matter how fine his TV reception, no beer-and-armchair quarterback can hope to see the true game. For all the paraphernalia, the tube rarely shows an overview; pass patterns and geometric variations are lost in a kaleidoscope of closeups and crunches.

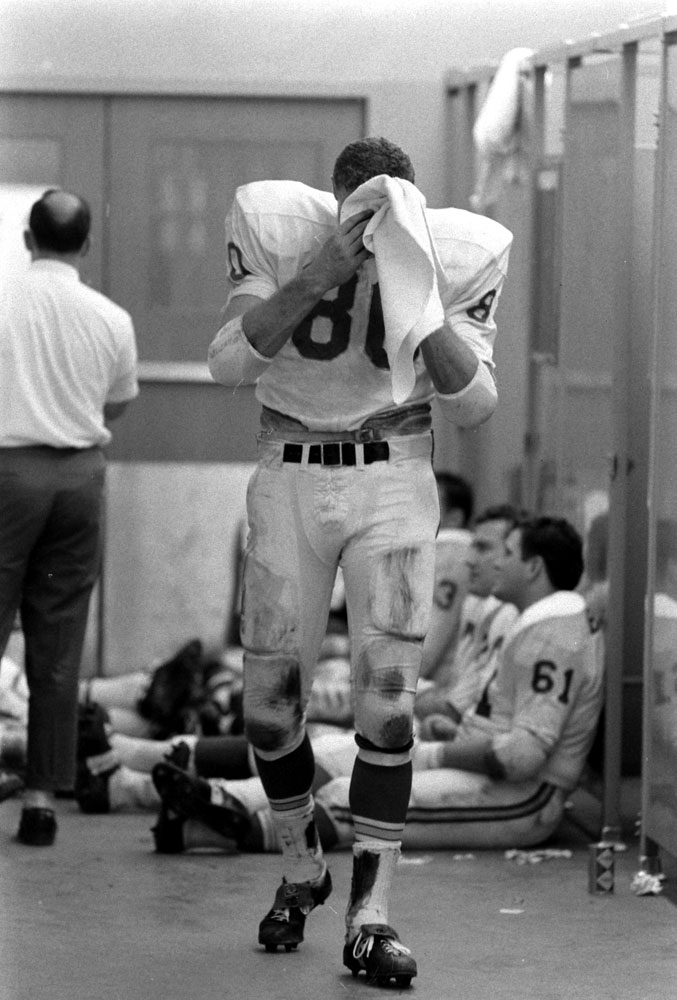

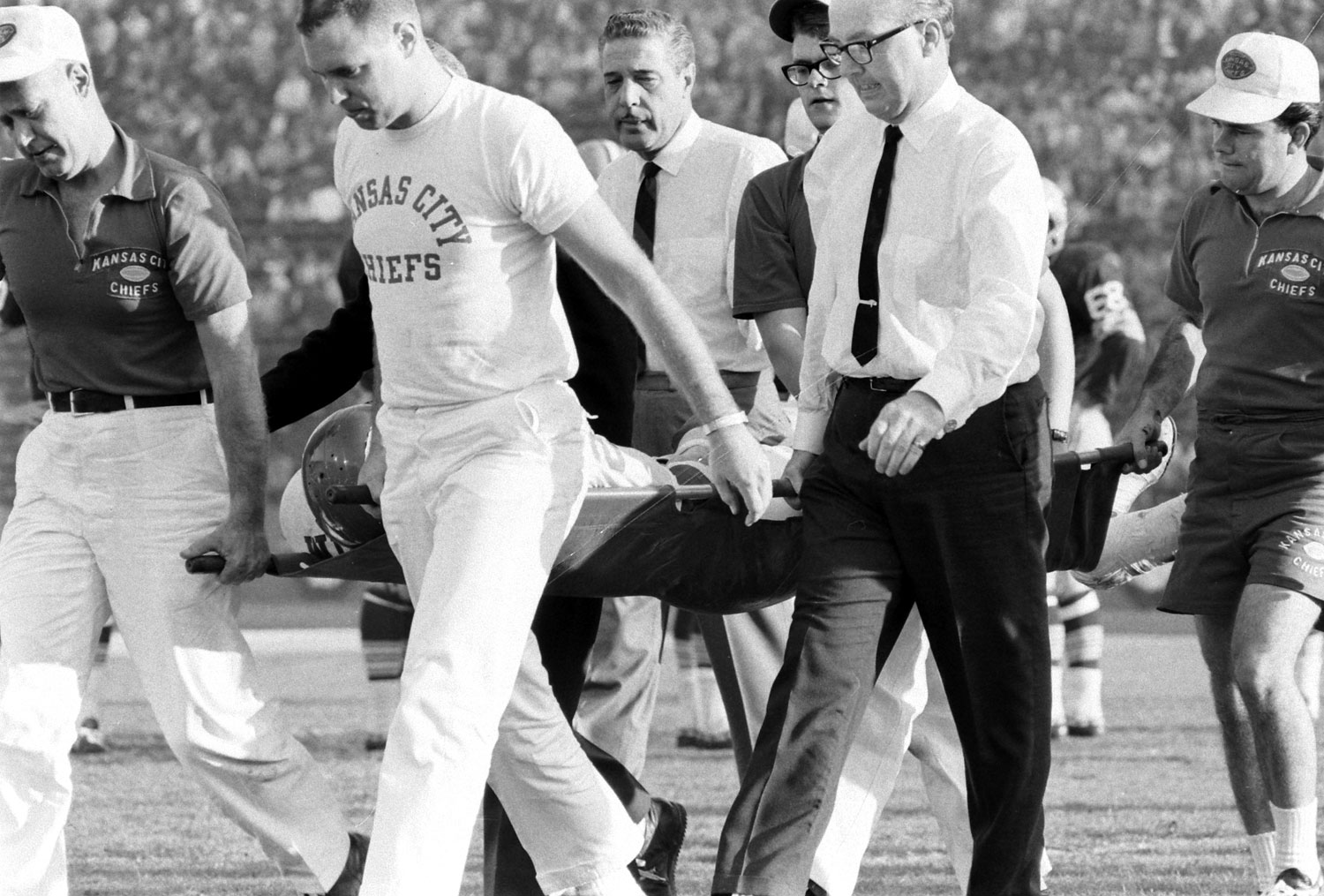

Still, the sense of martial art is conveyed; in its limited way, television has made the game so rich — in every sense of the word — that its players portray villains, heroes and fools all in the same afternoon. Through TV, the sport has become a high ritual of bloodletting. It is also, as always, a morganatic wedding of cold mathematics and glorious physical achievement. It is, as well, a confused and pointless scramble across 100 yards of meaningless turf.

This Sunday, you can watch that scramble at 6:30 on NBC — high ritual and all.

Read TIME’s original coverage of Super Bowl I here in the TIME Vault: Bows Before the Bruises

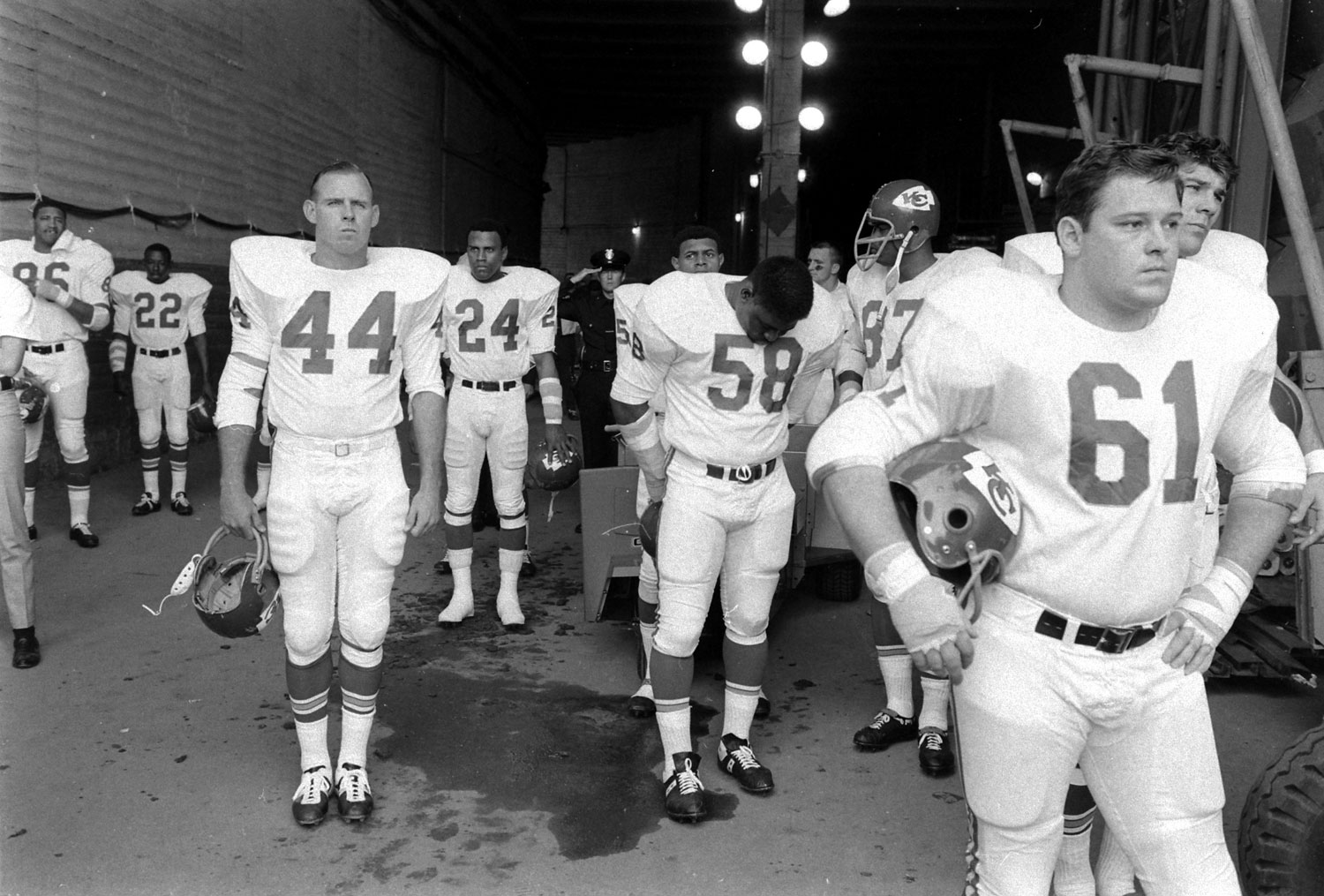

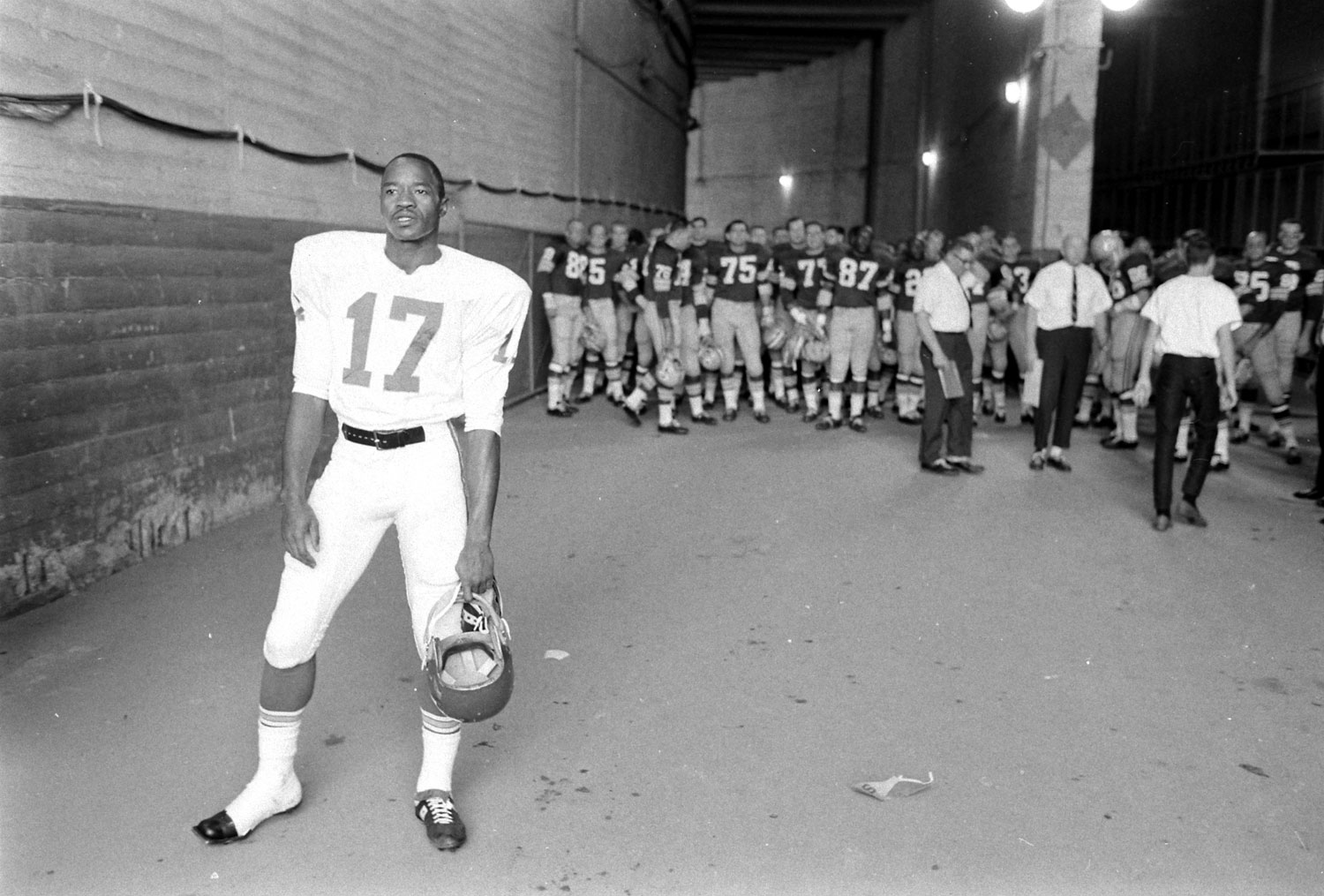

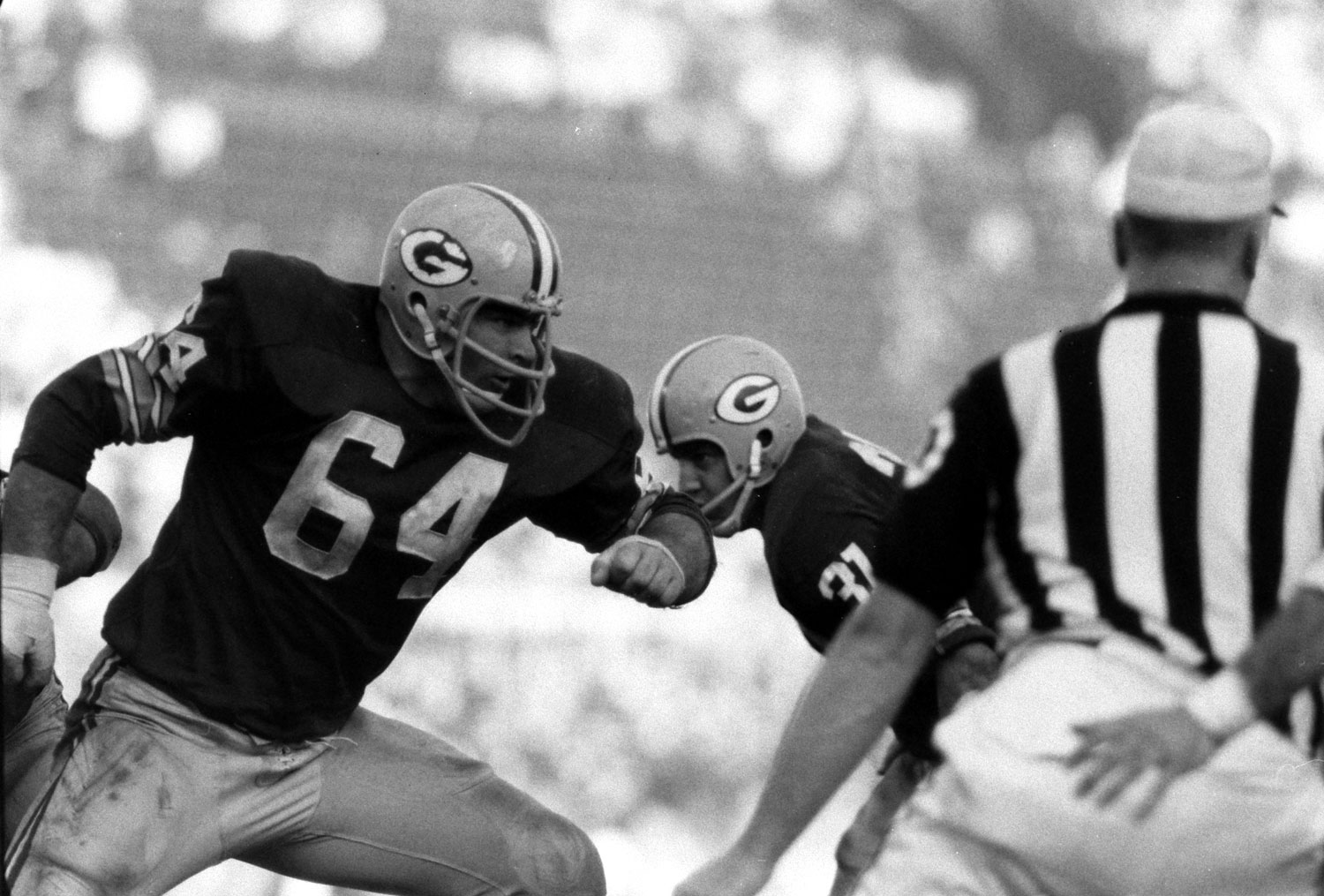

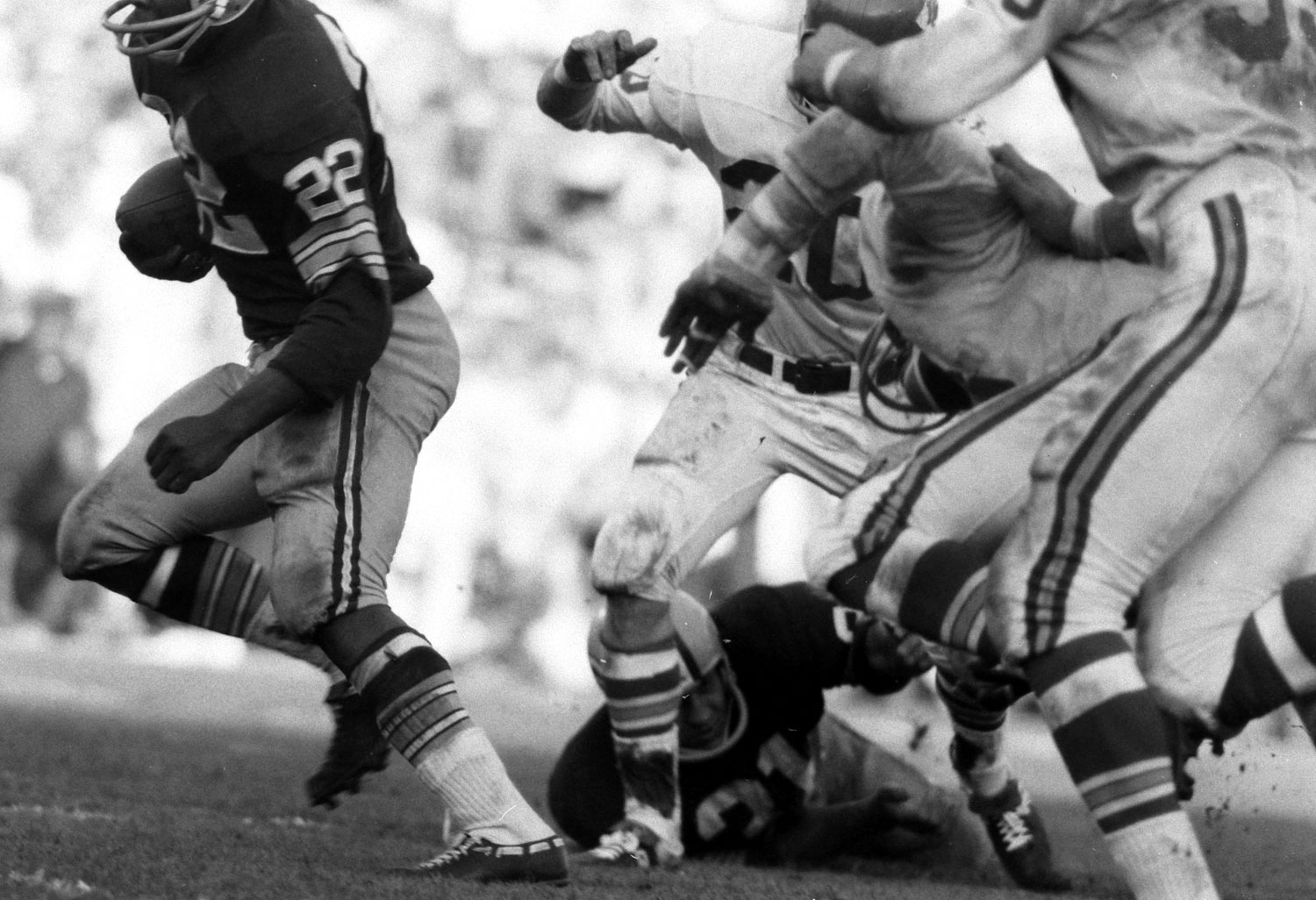

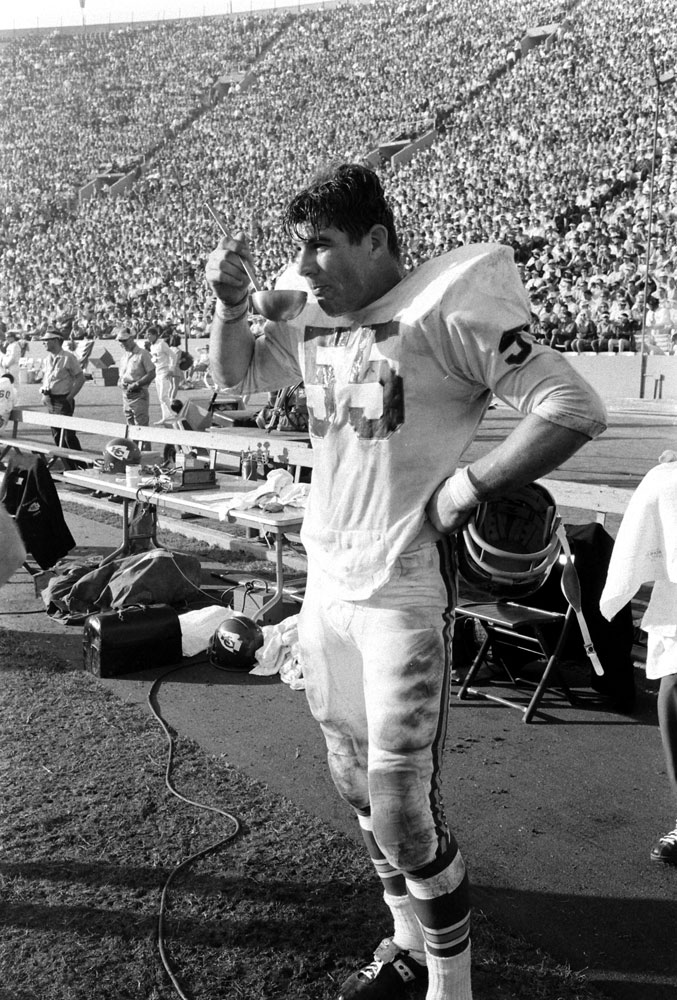

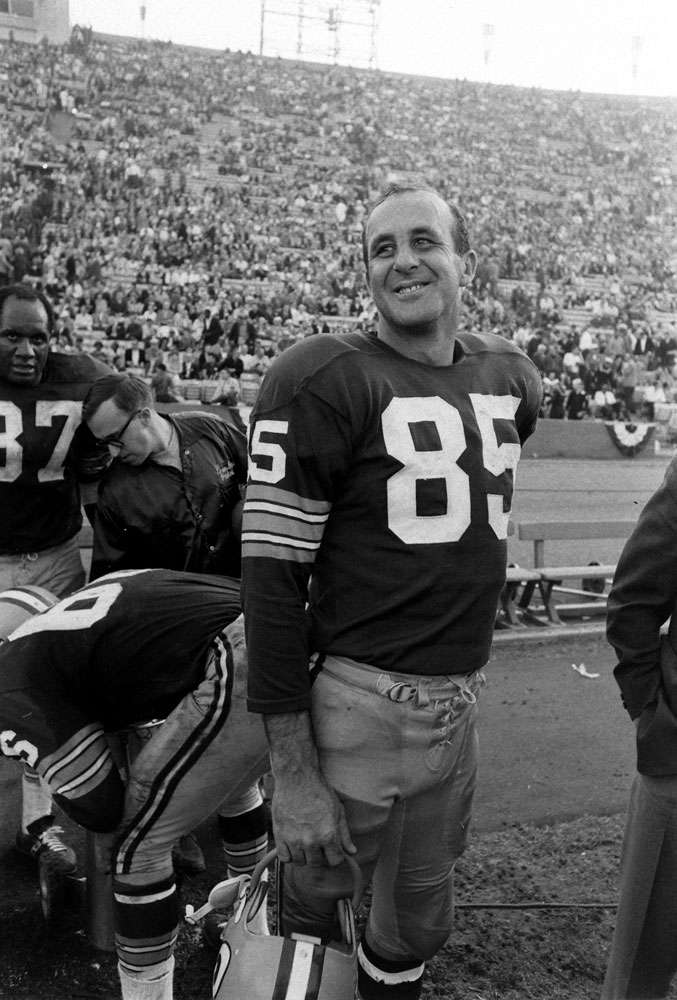

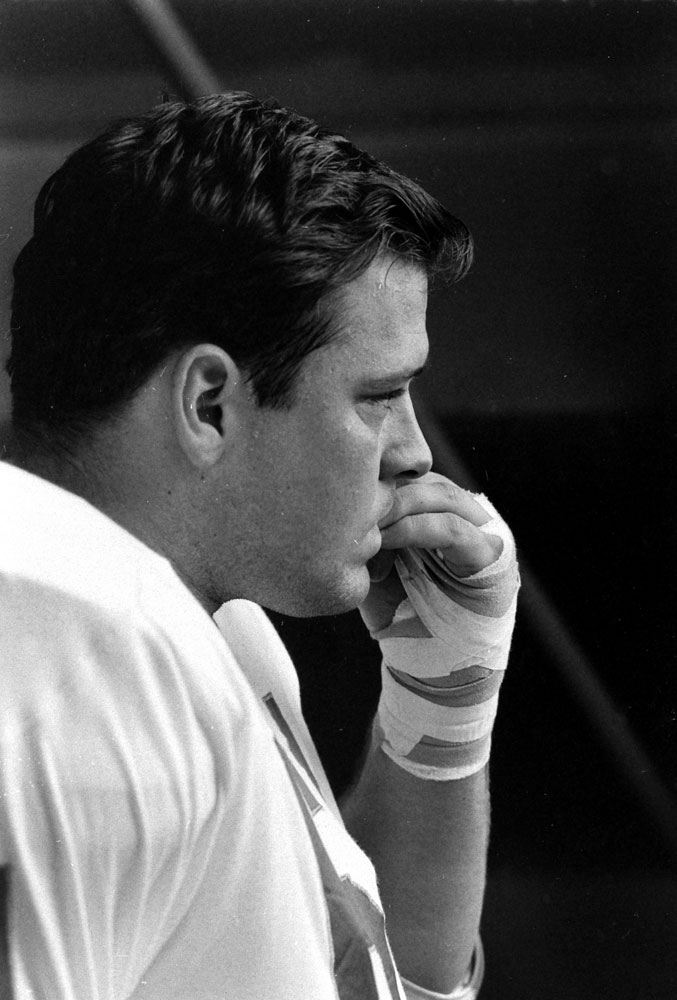

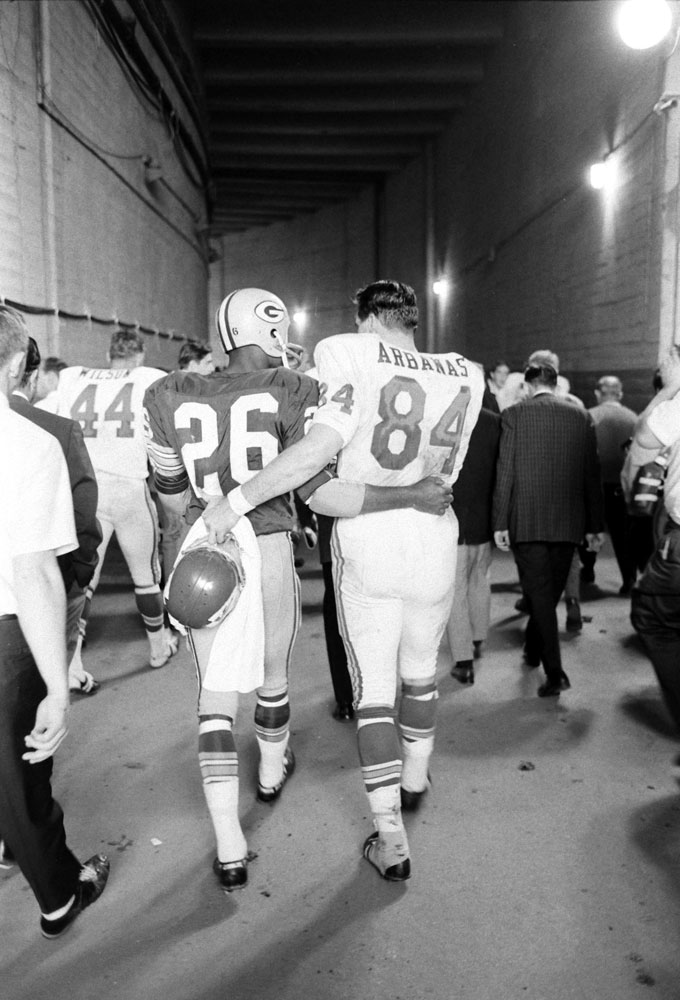

The First Super Bowl: Rare Photos From a Football Classic

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com