The casual student of history might not look to Frederick Douglass for wisdom on the power of photography. The abolitionist is best known for his unmatched talent for oration, and when he died in 1895, the medium was still an evolving technology. But Douglass knew that photography had a quality that couldn’t always be found in other art forms. He touched on the transformative energy of the image when he wrote in 1864 that making pictures enables us to “see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.”

Douglass’ words introduce a selection of some of the most iconic photographs of African American history in the new book Through the African American Lens, curated by Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, slated to open next year in Washington, D.C. The book is the first in a series, and an exhibit of the same name will open on May 8, 2015.

“The book essentially reflects the vastness and the dynamism that is the subject matter for the museum,” says Rhea Combs, Curator of Film and Photography at the museum, who led the team that distilled a collection of 15,000 images into the 60 photographs that make the book. While future books will delve into more specific themes in African American history, like the civil rights movement and African American women, the first book takes a sweeping look at more than 150 years of the vast and varied set of African American experiences in America.

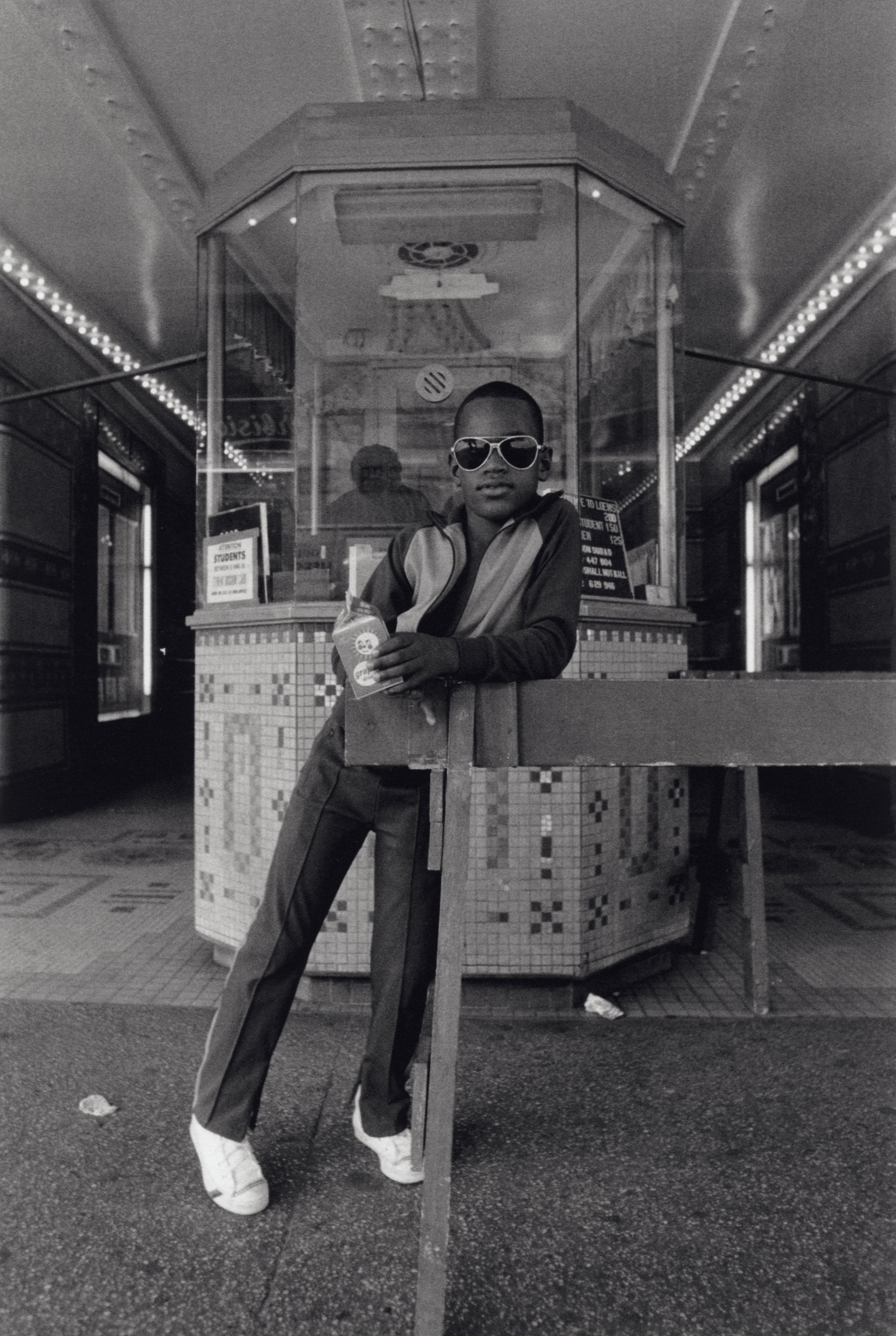

Throughout history, photographs have afforded African Americans a way of “inserting themselves into a conversation,” Combs says, especially in a society “that oftentimes dismissed them or discounted them.”

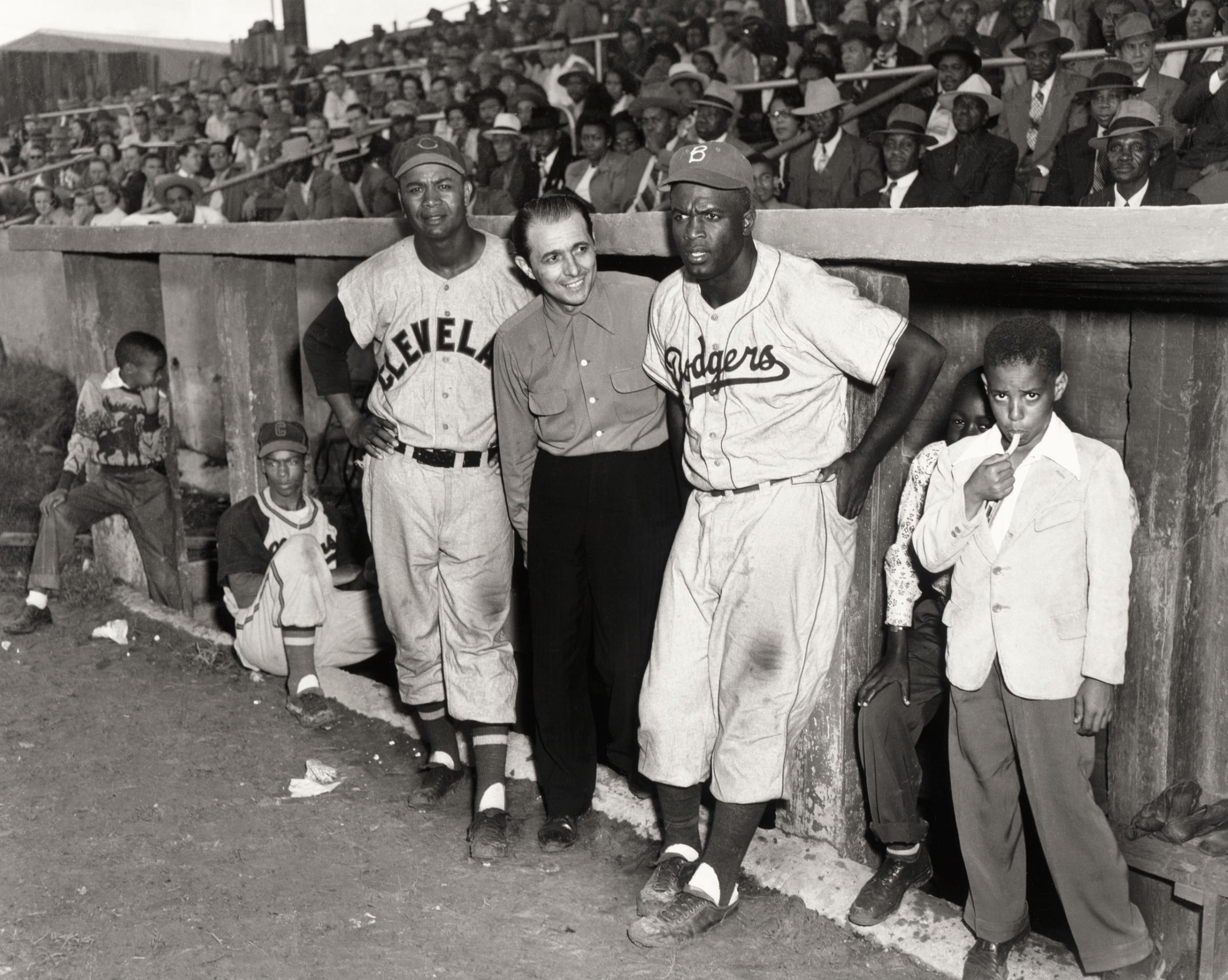

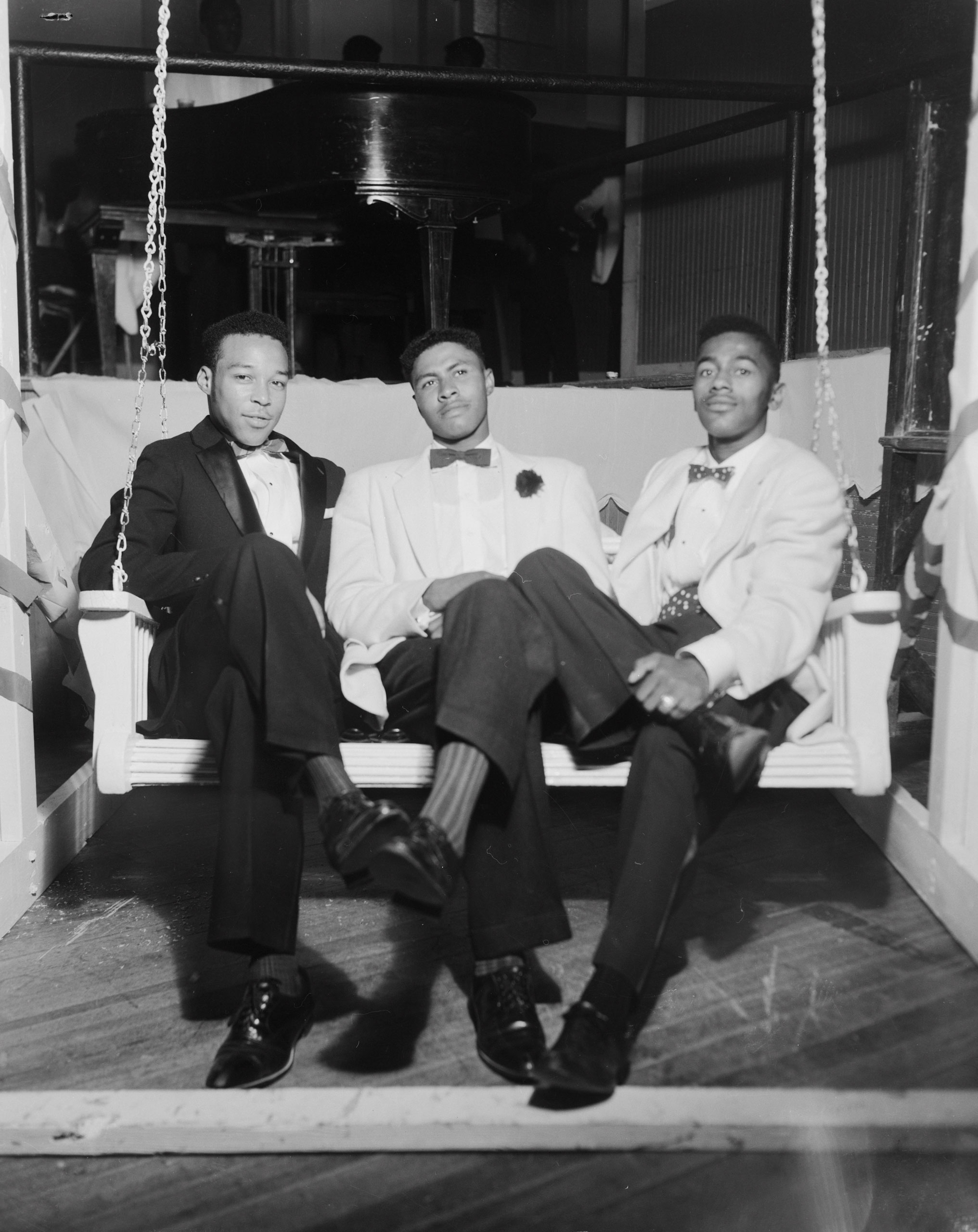

The images reveal how agency can be created in the space between lens and subject. “There is a real, conscientious effort with individuals that are standing in front of the camera to present themselves in a way that shows a regality, a fortitude, a resolve,” she says. Whenever Douglass was photographed, he made sure to see the photographs before they were distributed, as he knew the importance of controlling his image. During the mid-nineteenth century, abolitionists mailed out photographs of slaves in an effort to change hearts and minds on the matter of abolition.

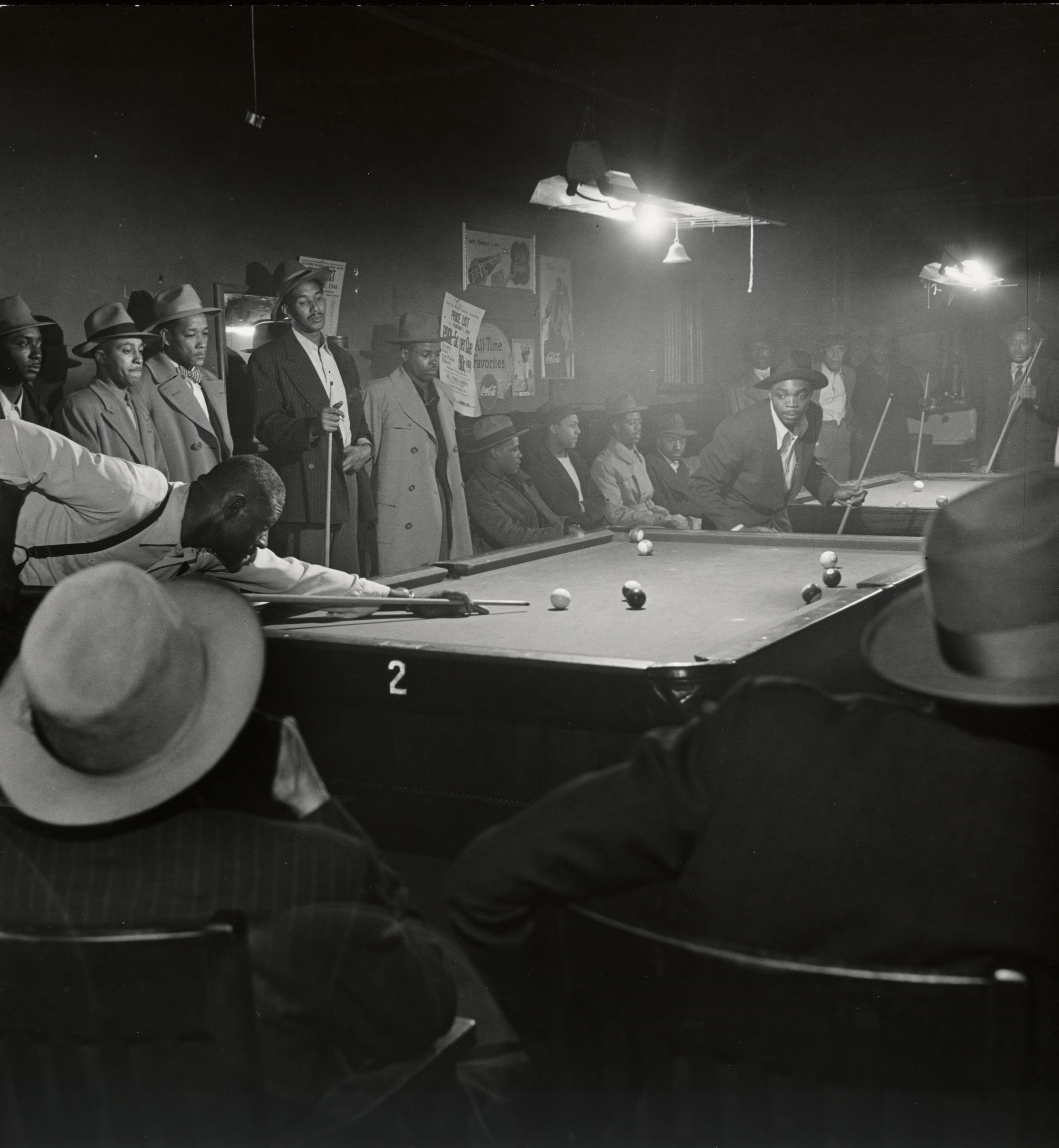

Many of the photographs were taken by photographers who were not African American themselves. When Wayne Miller, a white photographer, knocked on the doors of black Chicagoans in the 1940s, he earned their trust through conversation rather than setting out to conduct an anthropological study. Though this was certainly not always the case, and the relationship between subject and photographer can be quite complicated, “I think the agency was definitely in their gaze at the camera instead of the camera recording them,” says Combs.

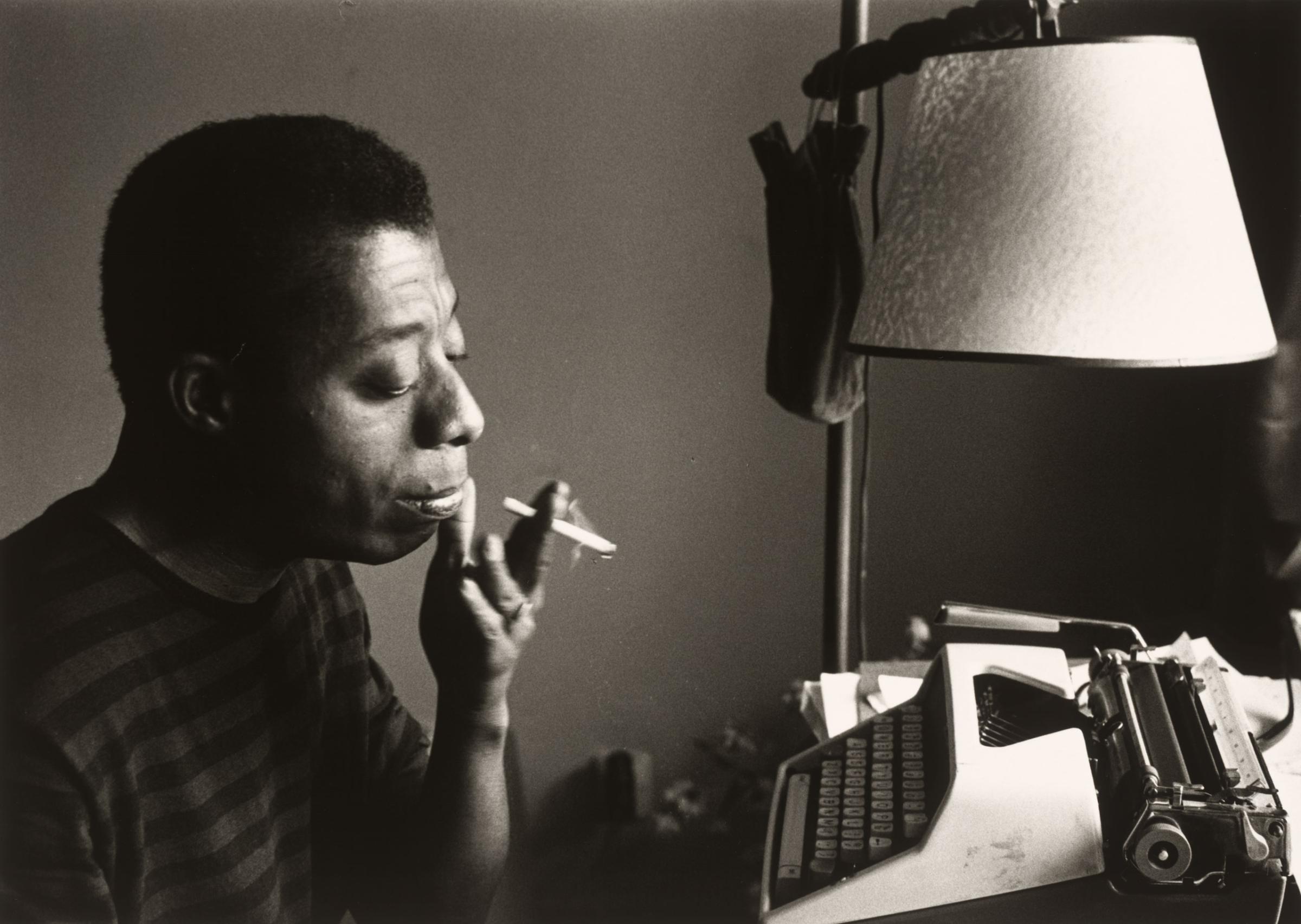

Sixty might sound like an impossibly small number of images to capture all of African American history. But the images Combs and her team selected speak volumes. A 1938 photograph of a Harlem Elks Parade shows, rather than the parade itself, the sense of community and togetherness among its spectators. Images of exile—in the form of James Baldwin and Eldridge Cleaver—speak to, in Combs’ words, “freedom movements that are part of American history, but didn’t occur on American soil.”

LIFE photographer Eliot Elisofon’s photo of Zack Brown photographing two men in Harlem is a fitting choice for the book’s cover. In it, a black photographer, behind the lens, documents the dapper and dignified appearance of two black men in Harlem. The photograph is about urban life and the Great Migration, but it’s also about photography itself: that interplay between the voyeurism of viewers and the self-awareness of subjects that brings a static image to life nearly 80 years later.

Many of the photographs have this sense of immediacy, a sometimes startling relevance that belies their age. In a picture taken by Dave Mann of Emmett Till’s funeral in 1955, Till’s mother clutches a handkerchief in one hand and extends the other, searching, it seems, for balance. The track of a single tear, which appears to have fallen just before the shutter was clicked, is visible on her face.

“Especially on the heels of things that are happening now,” says Combs, “this story unfortunately—how many years later—feels very, very familiar.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com