Clint Eastwood has been a very, very big movie star for more than four decades, and his recent empty-chair-addressing turn at the GOP convention aside, he’s long been a Hollywood player whose every move, onscreen and off, matters.

Ever since his epic revisionist Western Unforgiven came out of nowhere 20 years ago to win four Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director, Eastwood has been a favorite of fans and critics alike. Before then, of course, he had a massive popular following, with his movies often making heaps of money, while Clint himself was viewed by most nephiles as little more than a good-looking, charismatic muscle-head. Never mind that when he directed films they usually came in on schedule and under budget: until Unforgiven (or, perhaps, 1985’s highly lauded Pale Rider), Clint was the guy with the gun, or the fists, whose acting range ran the gamut from grim to grimmer.

As Eastwood’s work has grown at least somewhat more nuanced through the years — see films, to name just a few, as diverse and ambitious as Bird, Gran Torino, J. Edgar and Invictus — more and more critics have been singing his praises as a genuine film auteur and a Hollywood treasure.

And like other American pop culture icons (Jerry Lewis comes immediately to mind) Eastwood has long been celebrated internationally as an artist, rather than just a box office draw. For example, he’s been awarded not one but two of France’s most prestigious cultural honors: in the 2000s he was made a Commandeur of the nation’s Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and later earned a Légion d’honneur medal.

[Buy the recently released LIFE “Icons” biography, Clint Eastwood.]

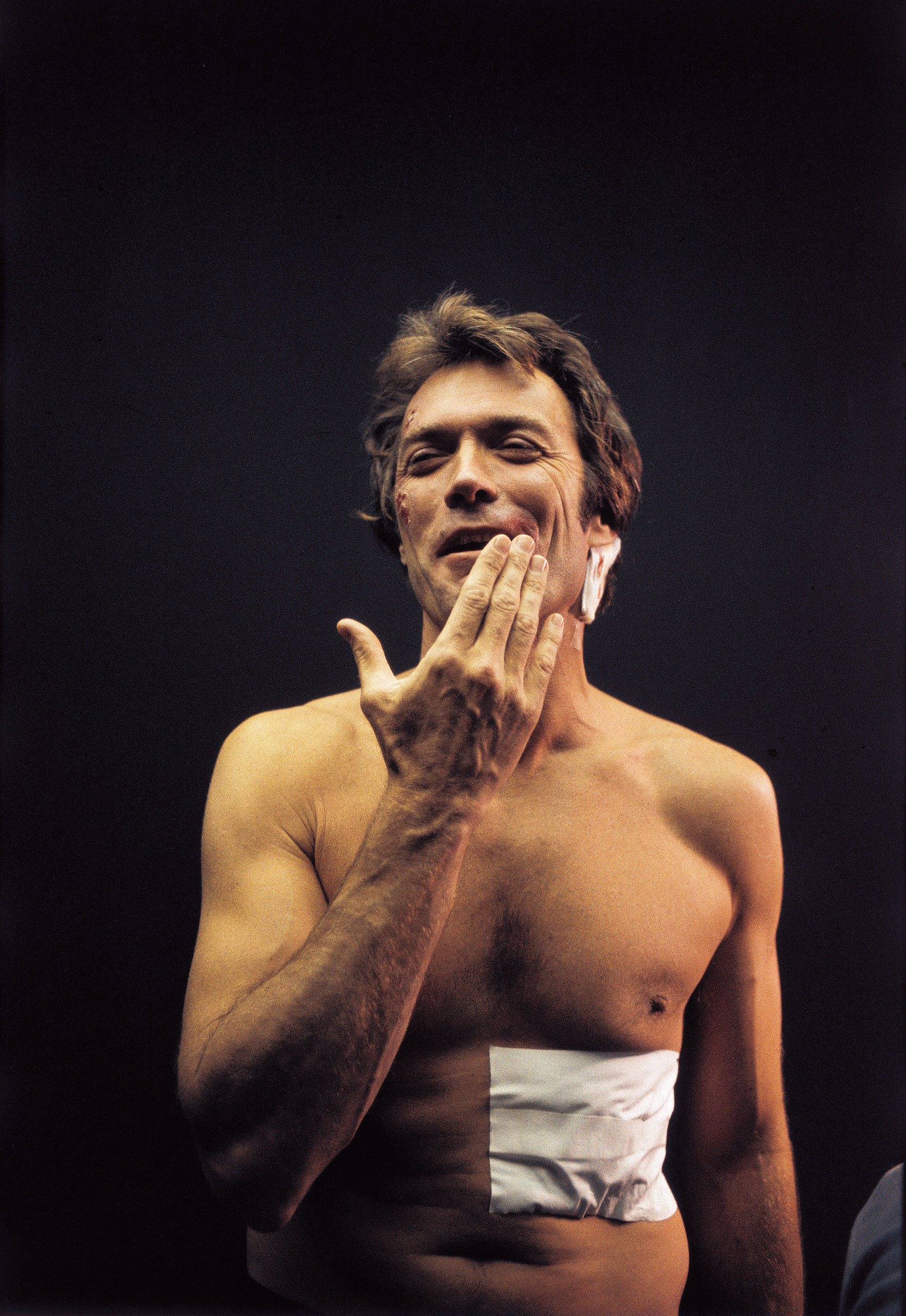

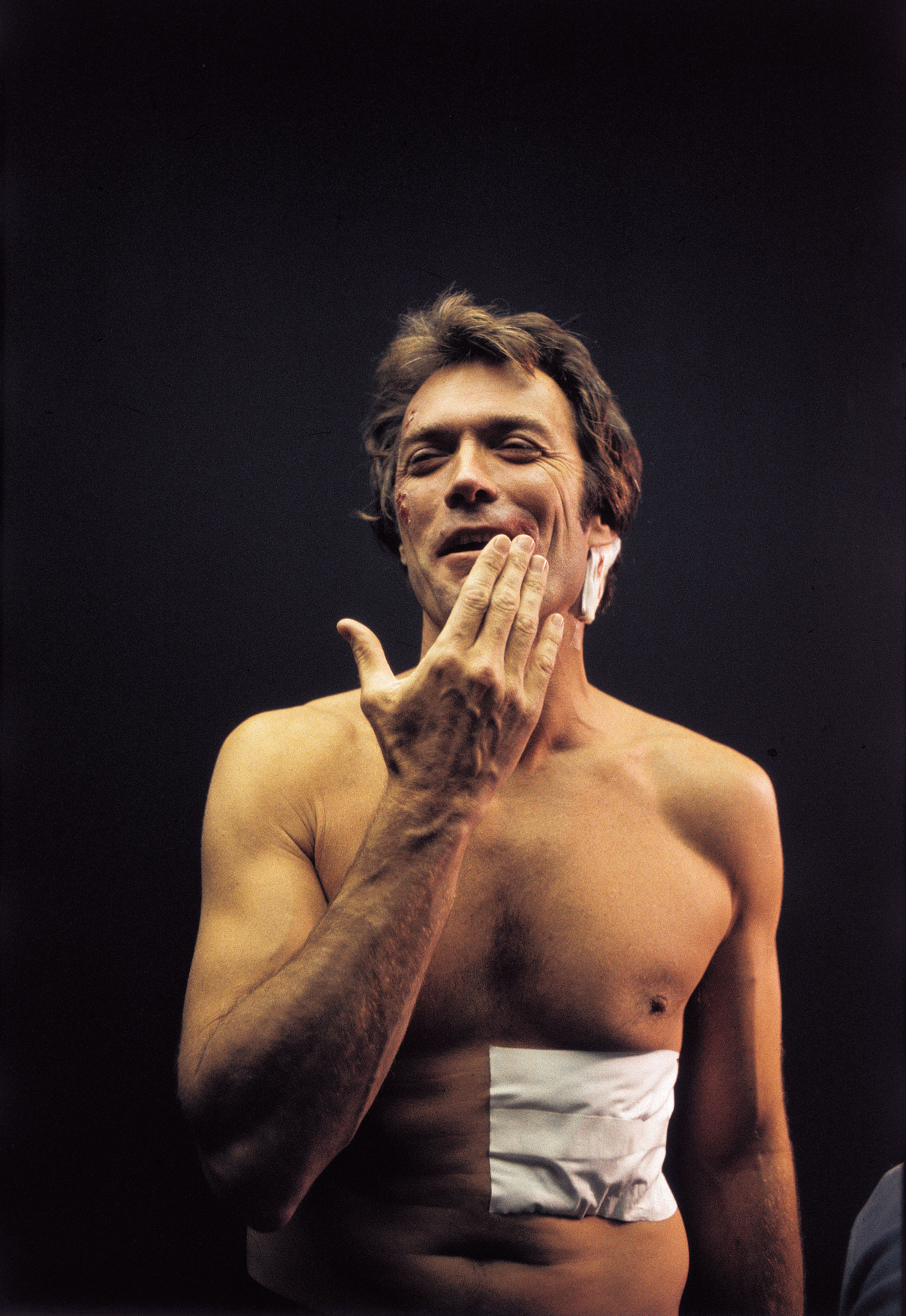

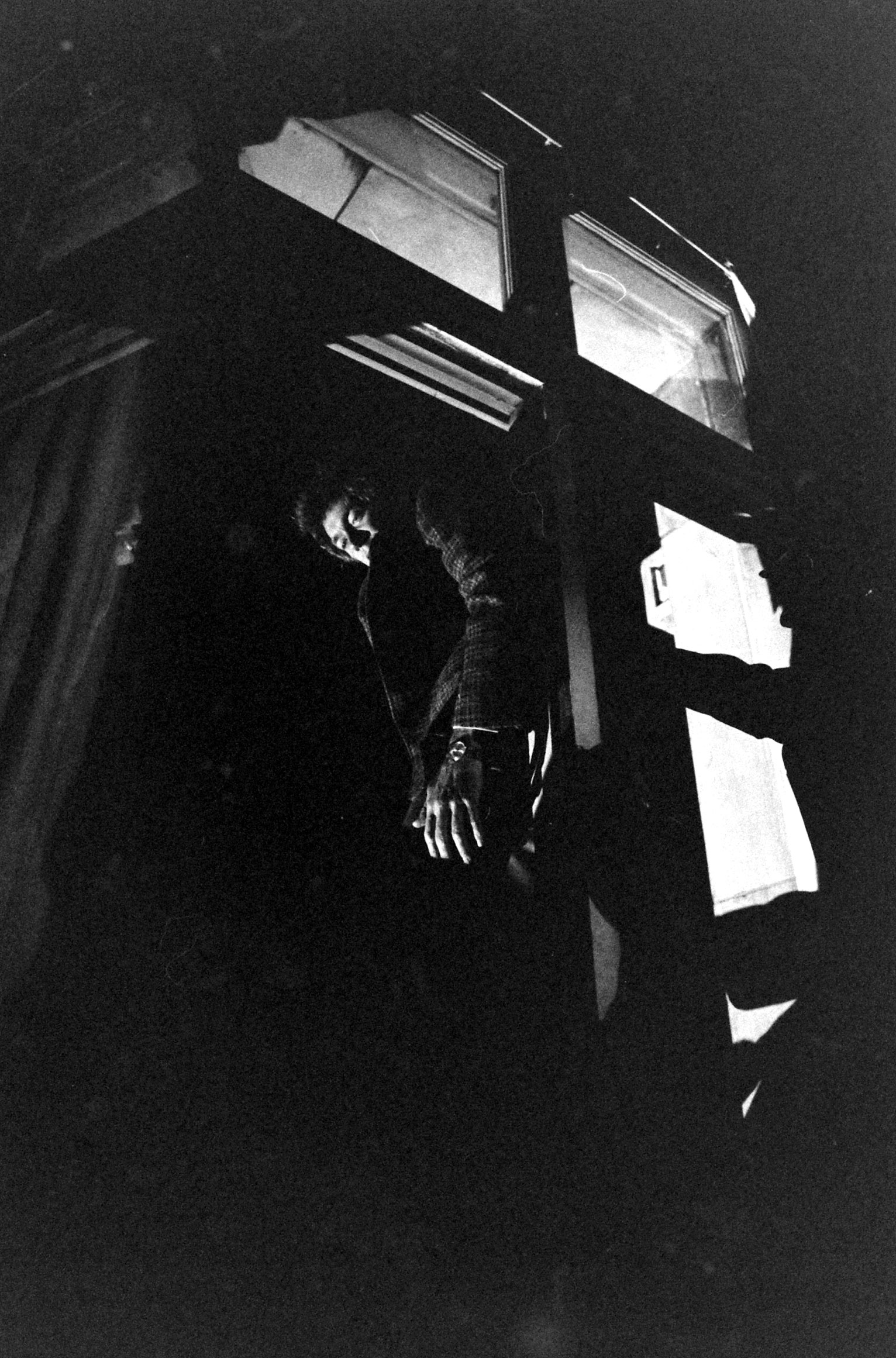

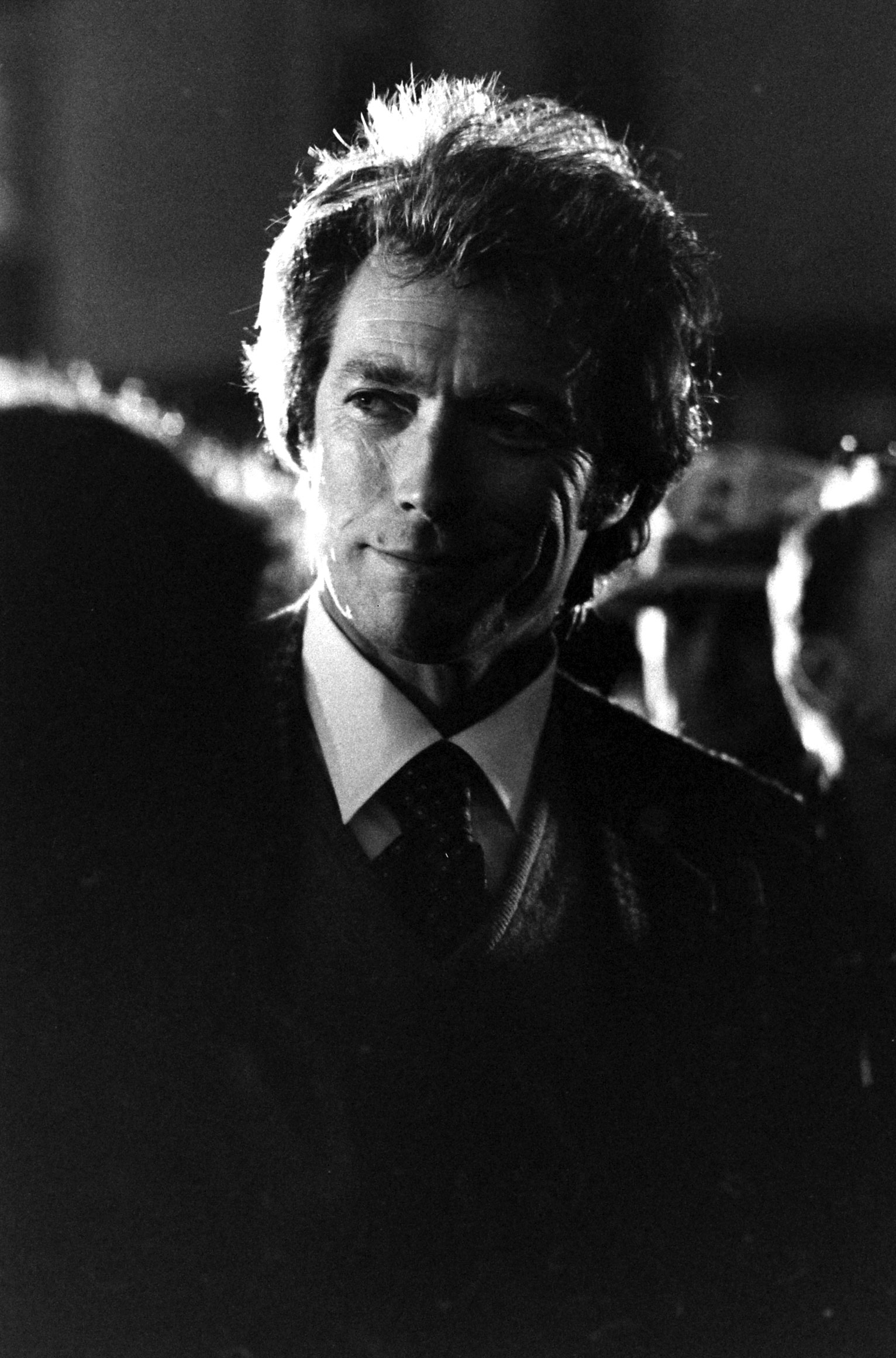

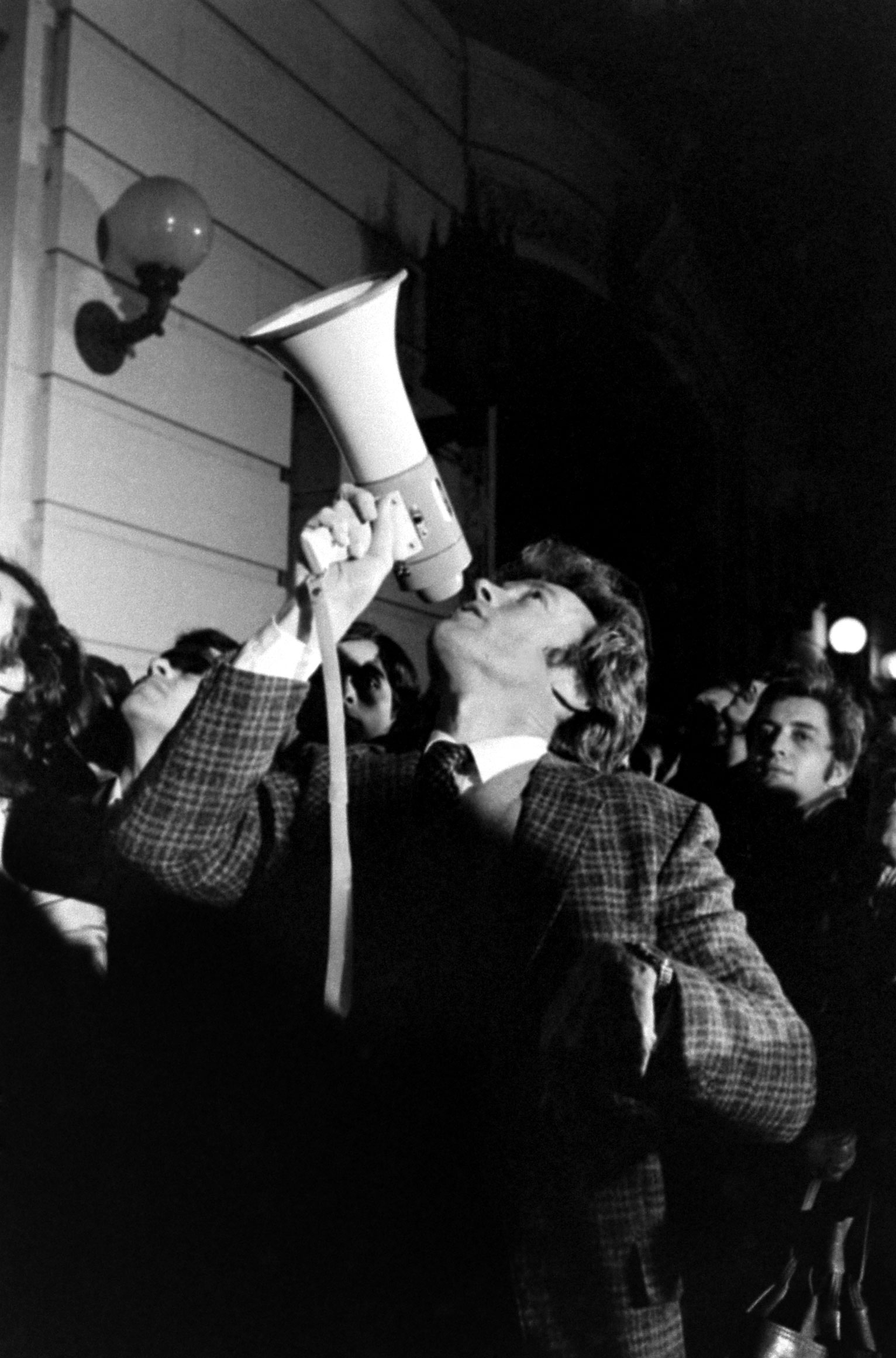

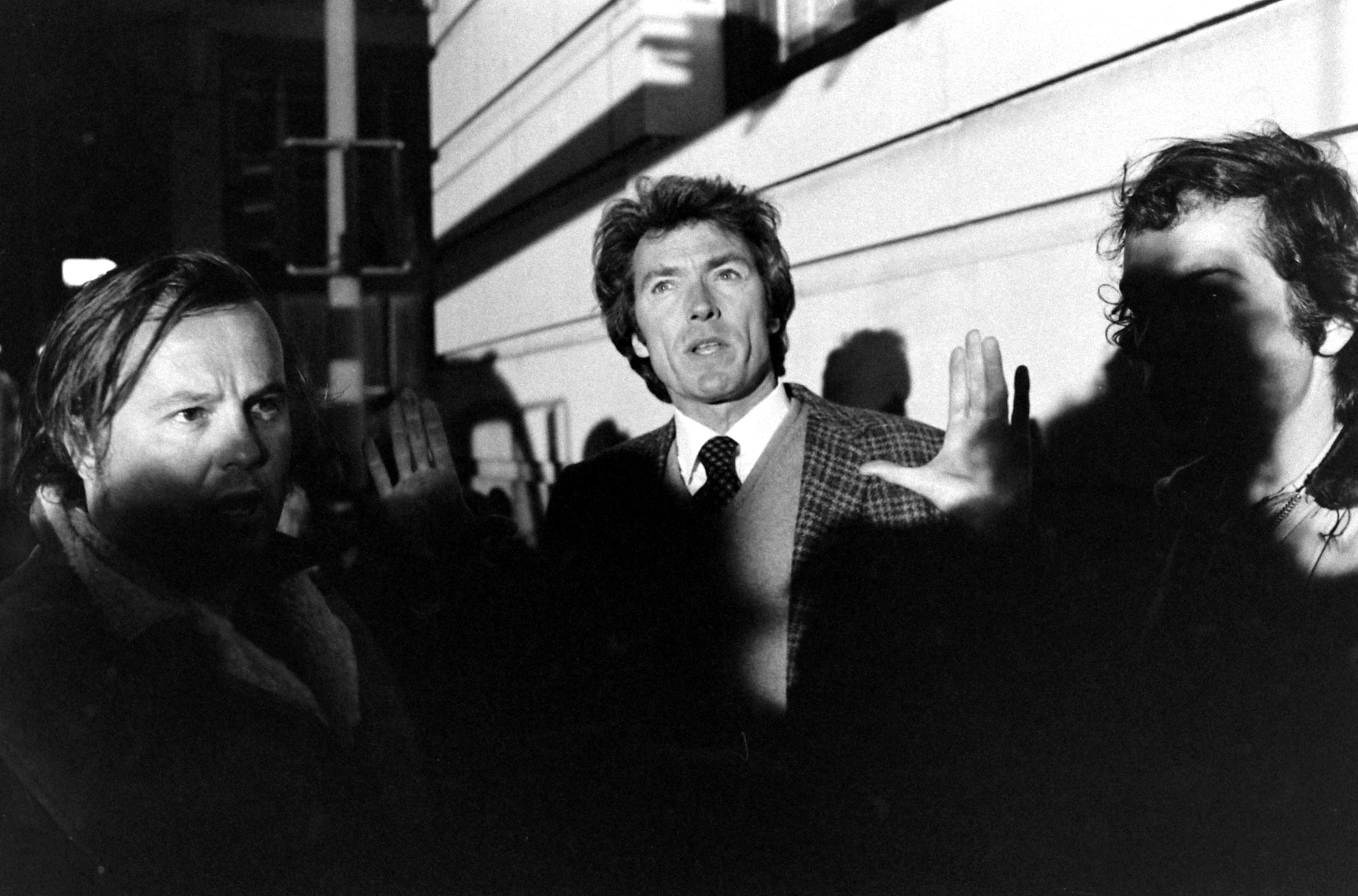

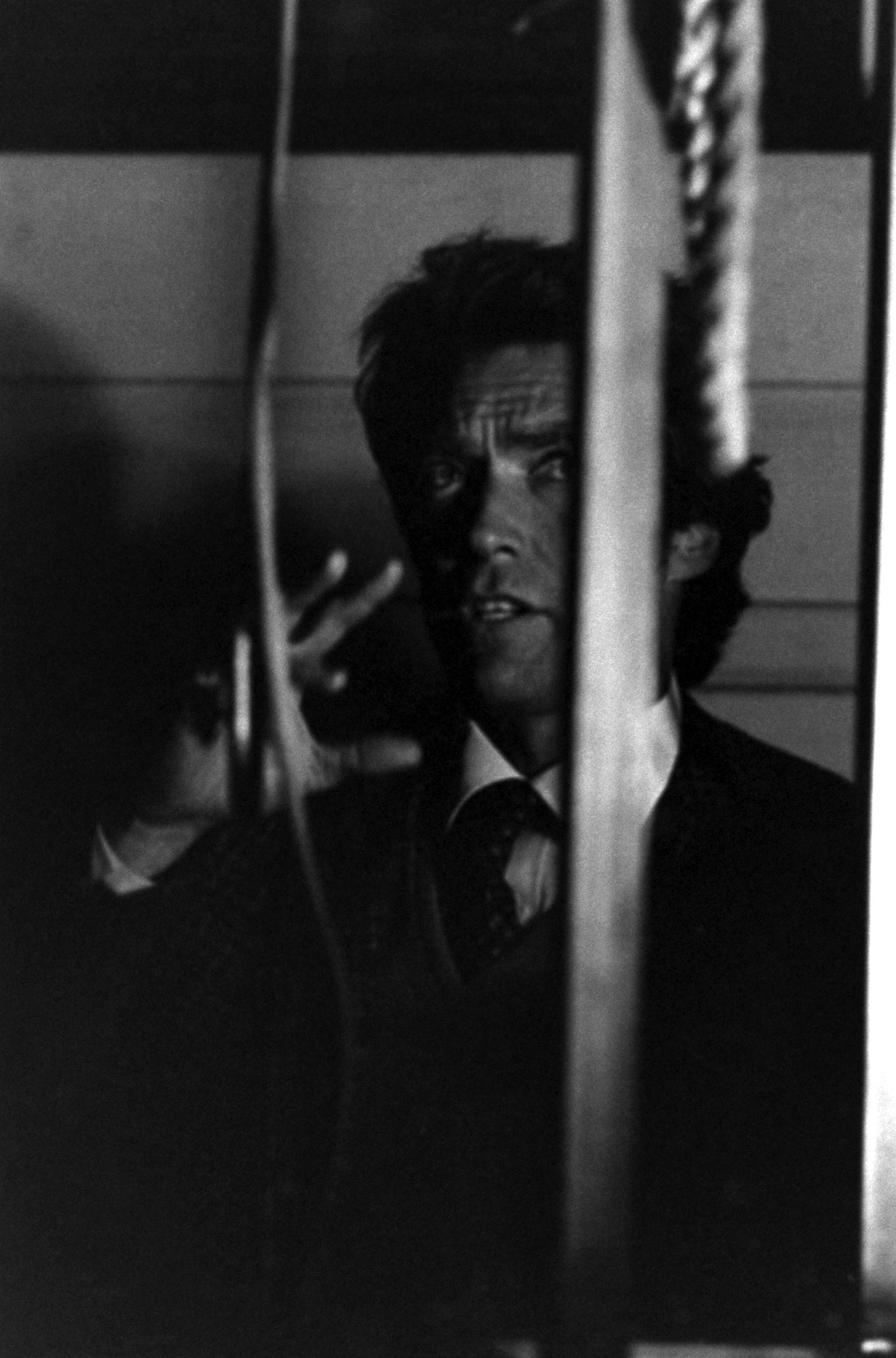

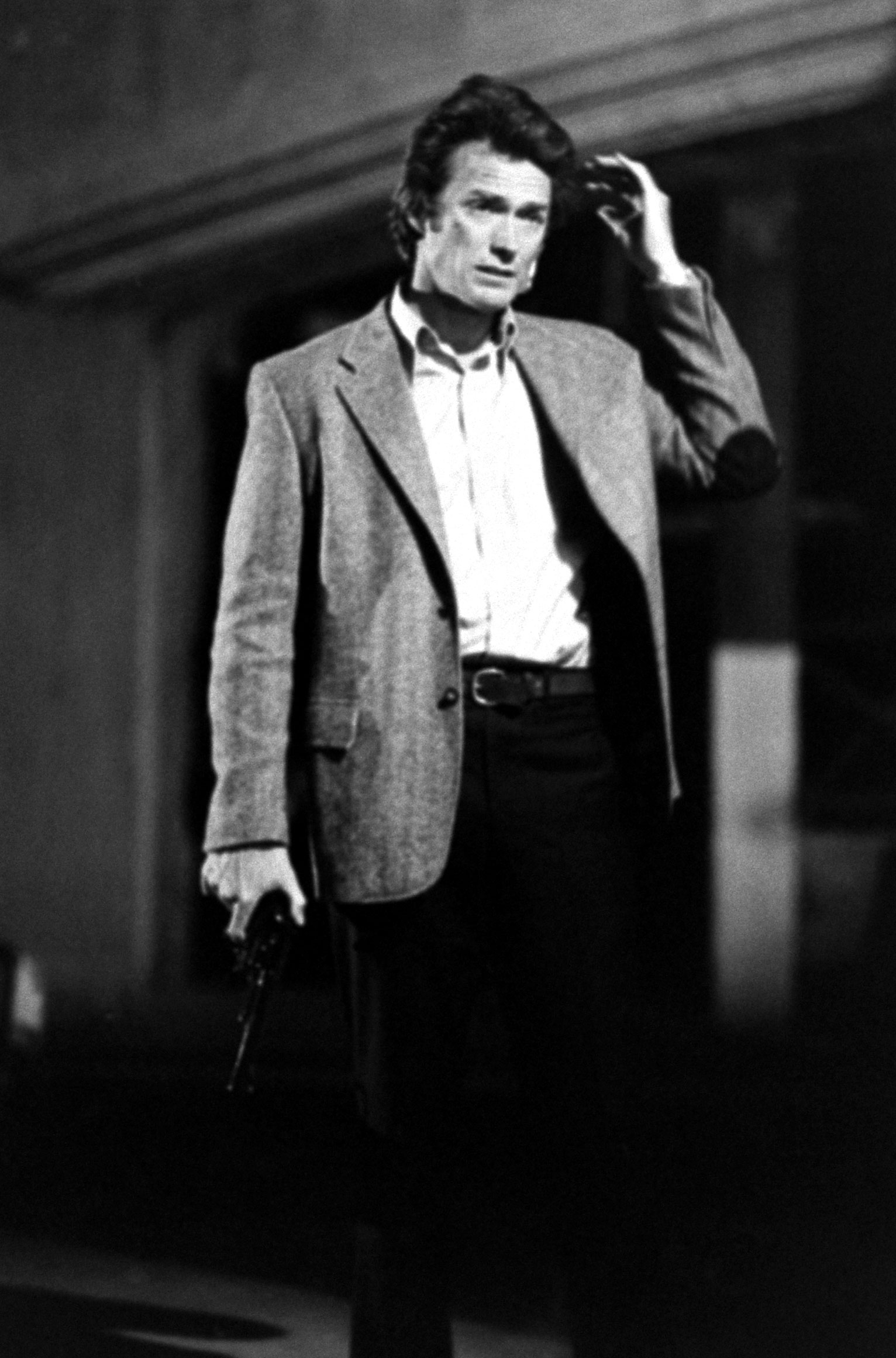

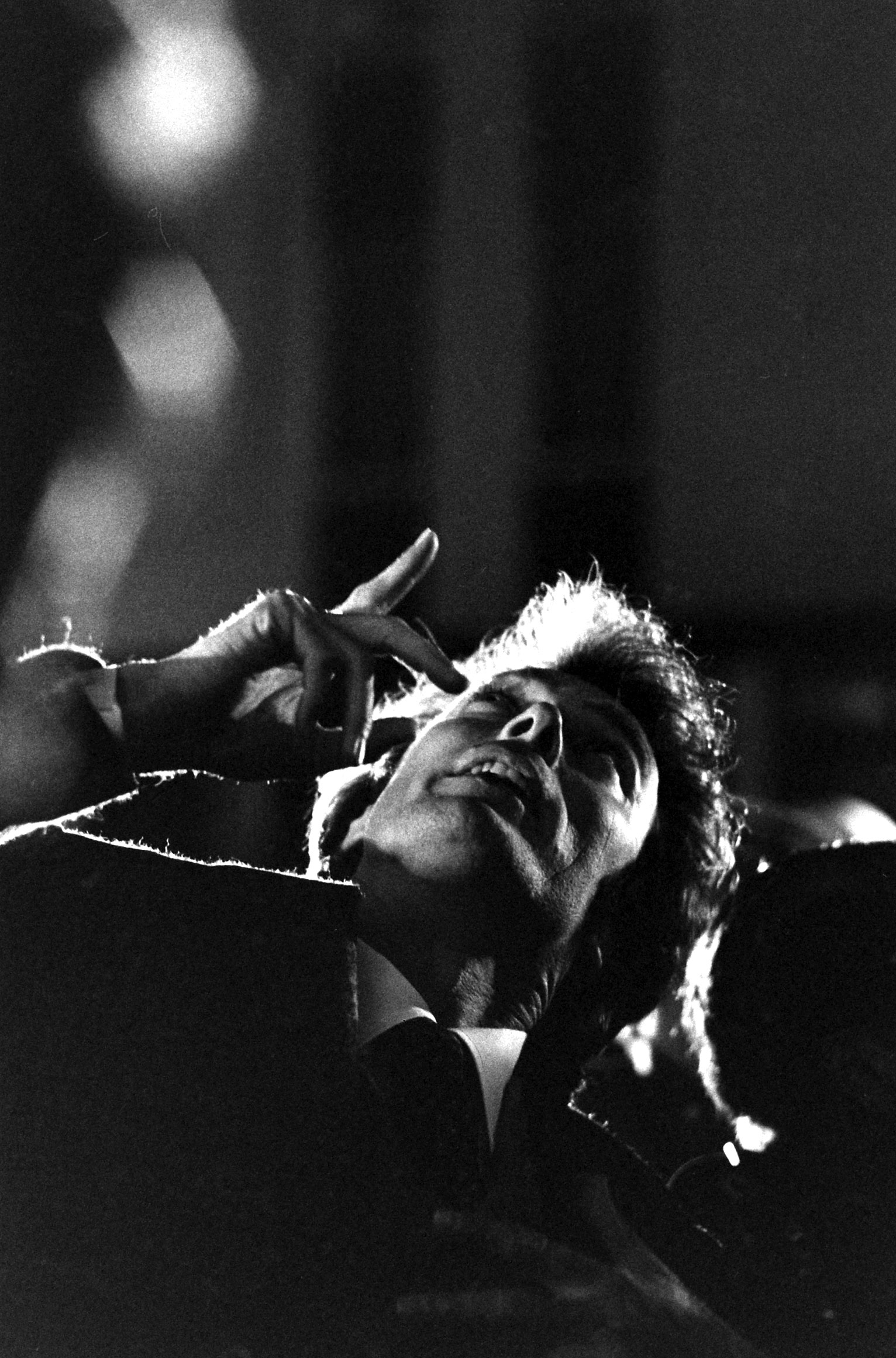

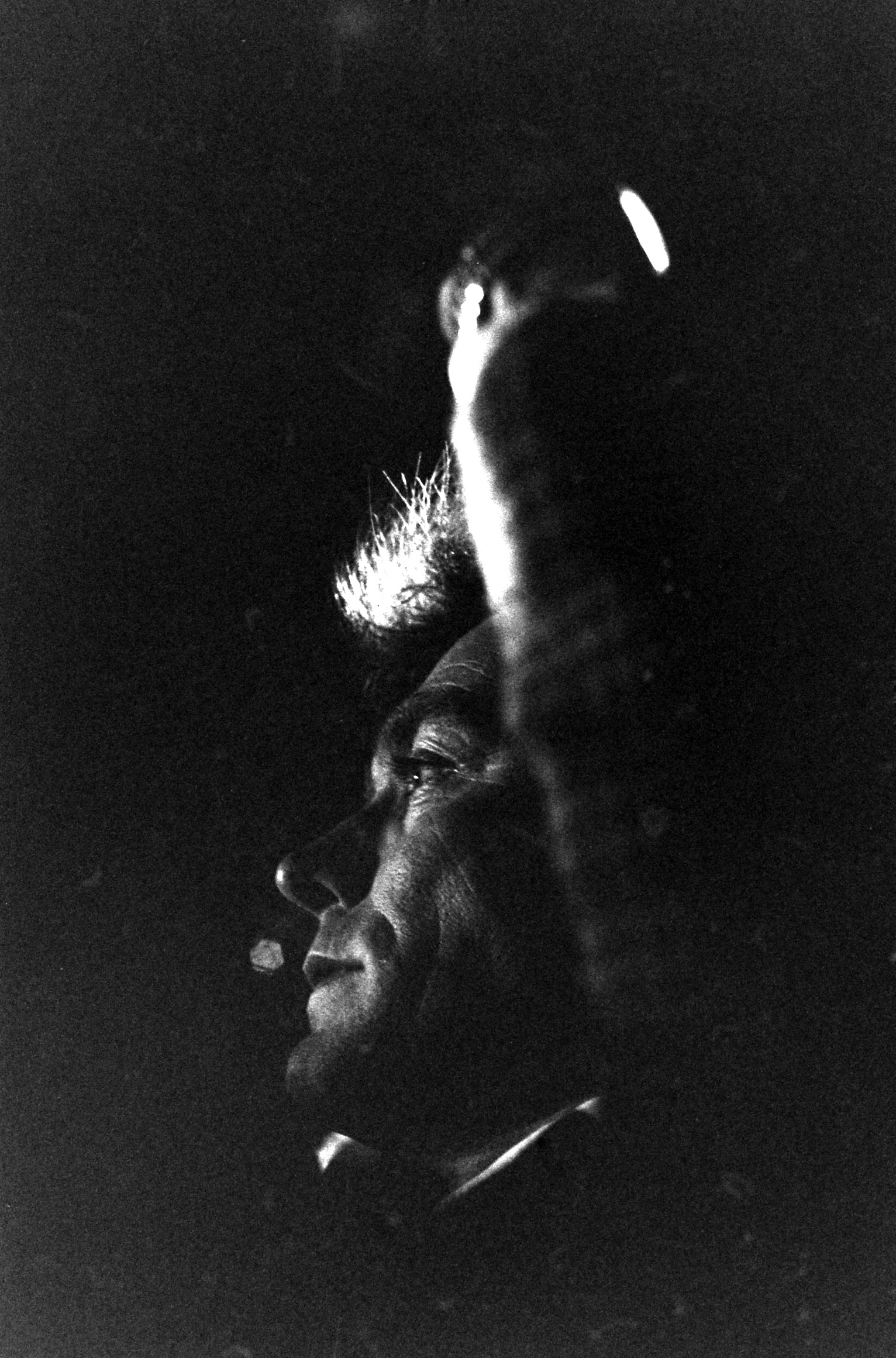

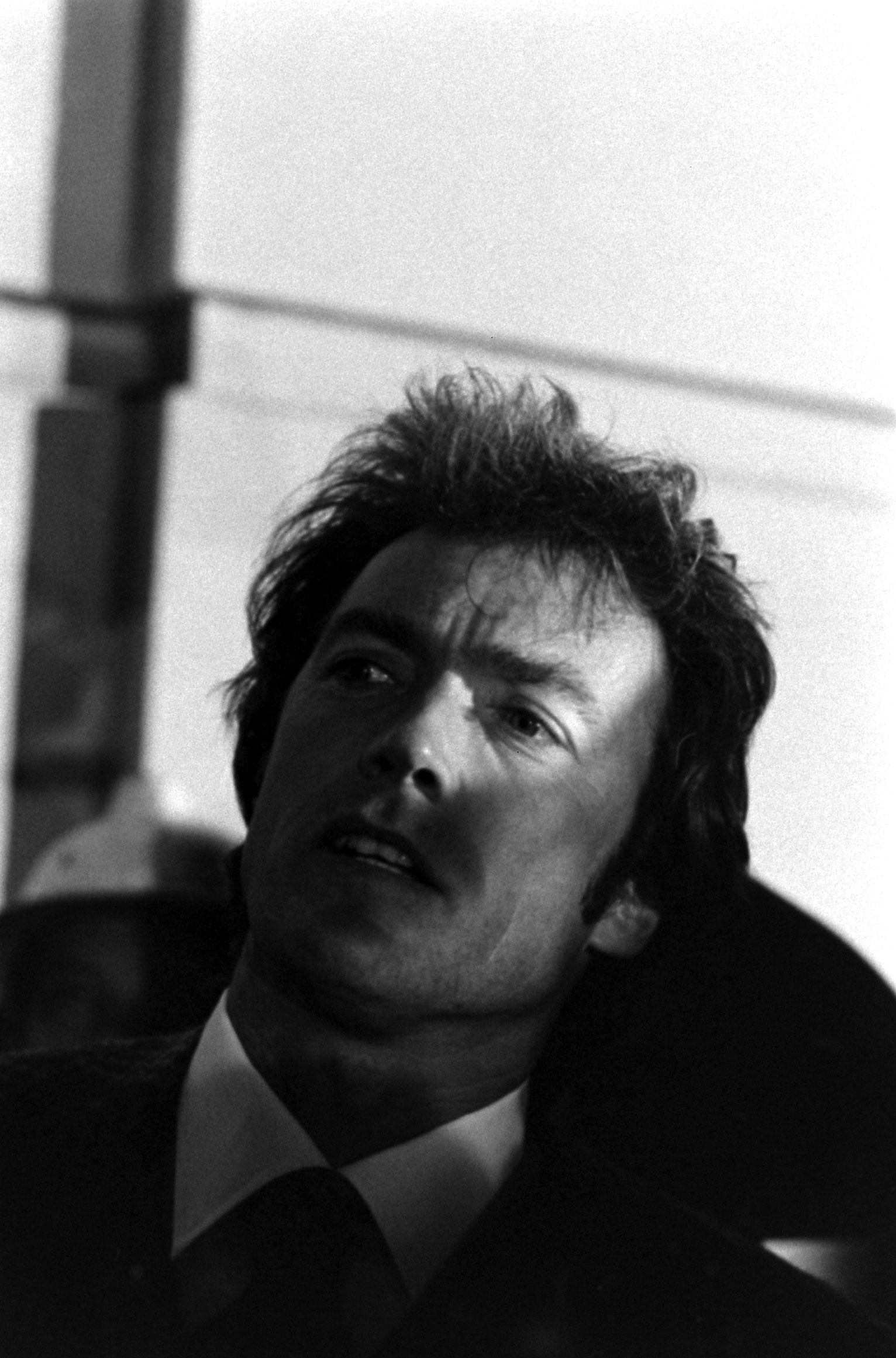

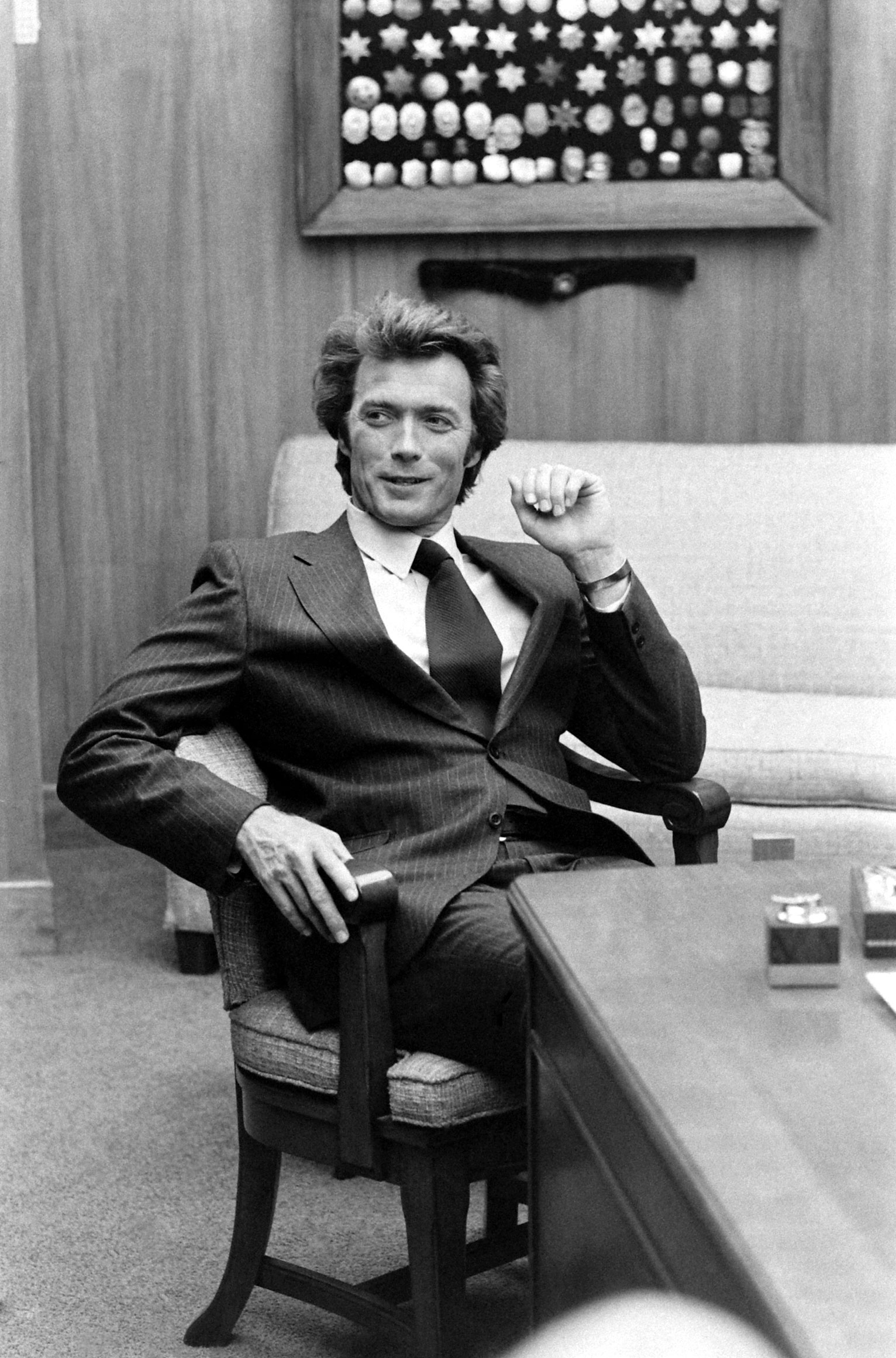

Here, LIFE.com honors the man with a series of pictures — most of which did not run in LIFE — by photographer Bill Eppridge in 1971. The images here were made on the set of a movie that would introduce a character with whom, for better or worse, Eastwood has been associated ever since: the brutal, gun-happy rebel cop, “Dirty Harry” Callahan.

But what’s also revealing — and all these years later, somehow kind of sweet — is the way LIFE talked about Eastwood in the cover story that ran in the magazine in July 1971, five months before Dirty Harry hit theaters and, quickly, became a controversial cultural touchstone. Right there, on the cover of the issue, is the (perhaps) tongue-in-cheek words observation that sets the tone for the profile inside: “The world’s favorite movie star is — no kidding — Clint Eastwood.”

Then there’s the title of the piece: “Who Can Stand 32, 580 Seconds of Clint Eastwood? Just About Everybody.” (The number refers to the time it would take to watch all the films in a nine-hour film festival of early Eastwood “spaghetti Westerns” that was running at the time.)

But even back then, Eastwood’s singular appeal as a Hollywood stud — with far more going on under the surface than most of his hits up until then might suggest — comes through. While his biggest fans (among moviegoers and critics alike) in 1972 could hardly have envisioned the esteem and the affection he would enjoy into his 80s, the Clint in the LIFE profile, and in these pictures, is a man clearly and fully at ease with himself. He’s a star who knows, as he says in the article, that “you have to give people good entertainment … If I started to pay too much attention to what the reviewers say, I’d have an ulcer.”

Four decades later, the reviewers are still trying to decipher Eastwood. And it’s clear that, four decades, later, he still doesn’t much care if they ever succeed.

Eastwood cover photo—Bob Peterson

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com