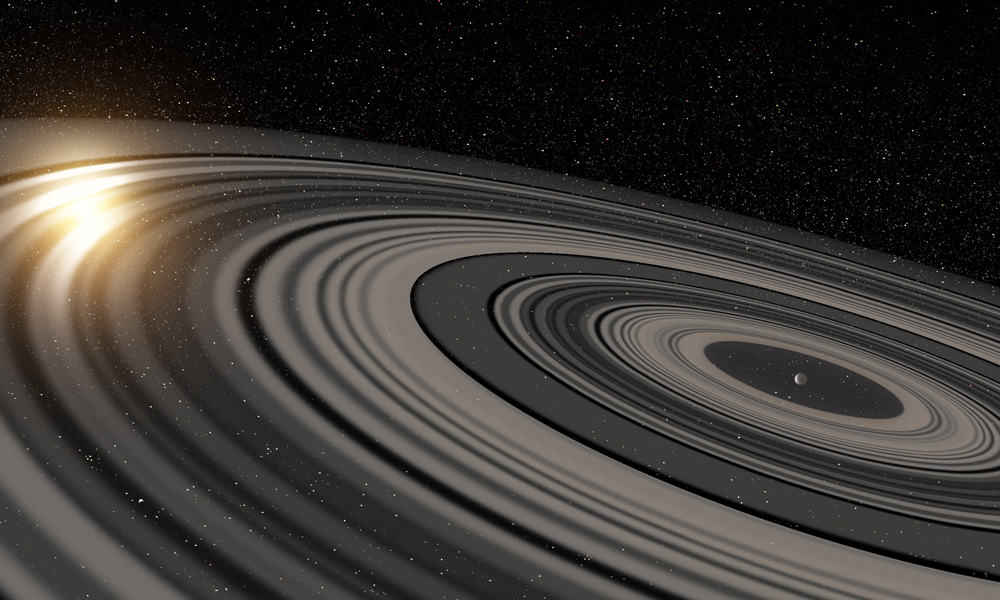

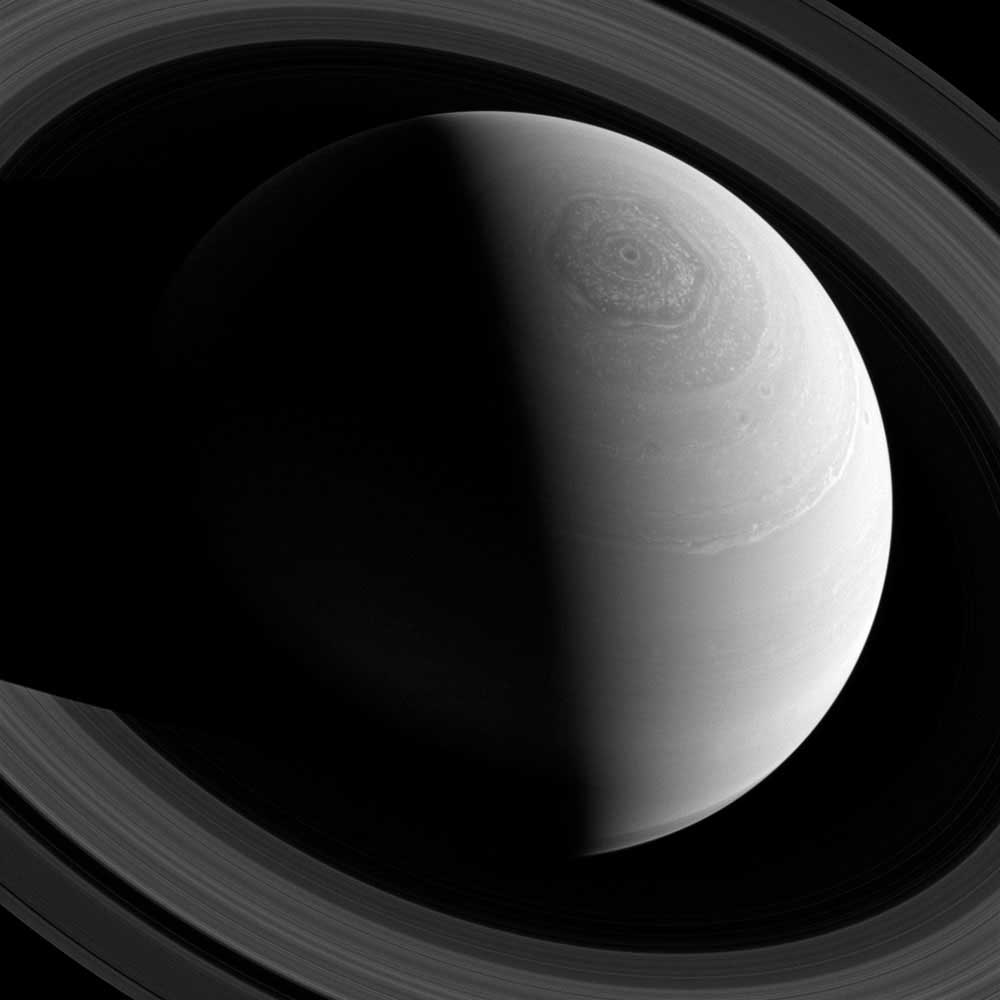

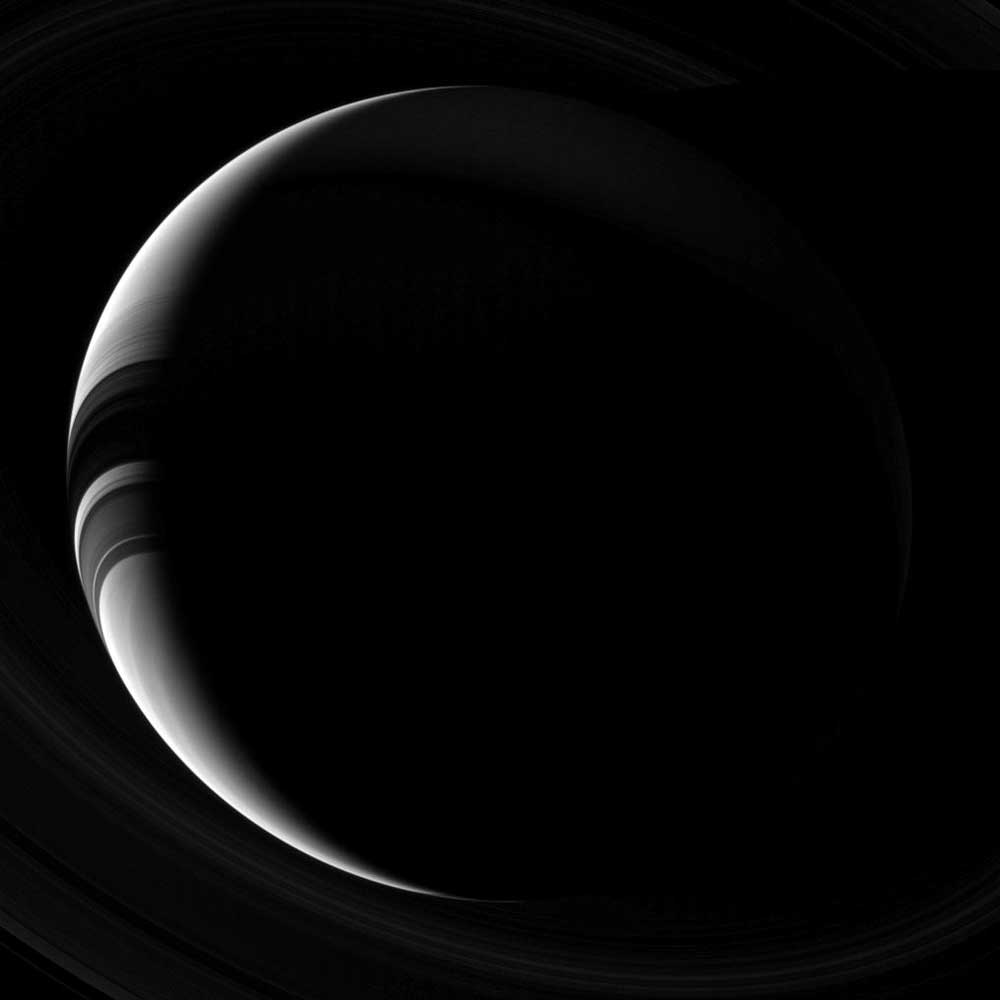

When the University of Rochester’s Eric Mamajek tells other astronomers about the object he and his colleagues discovered about 430 light-years from Earth, they tend to be skeptical—very skeptical. And no wonder: What he’s found is a giant ring system, sort of like Saturn’s, but some 200 times bigger, circling what may be an exoplanet between ten and 40 times the size of Jupiter. If you put these rings in our own Solar System, they’d stretch all the way from the Earth to the Sun, a distance of 93 million miles (150 km). And what’s more, there’s evidence that the rings are sculpted by at least one exomoon—something that also happens at Saturn, but not remotely on this scale.

MORE These ‘Vintage’ NASA Posters Imagine Travel Beyond the Stars

“It took us a year even to convince ourselves of what we were seeing,” says Mamajek, whose paper is based on a new analysis of observations taken back in 2007 by the SuperWASP planet search project. At the time, the observations seemed to make no sense: when a planet passes in front of a star, you usually see a dip in starlight that lasts for up to a few hours. In this case, the starlight dimmed for two months.

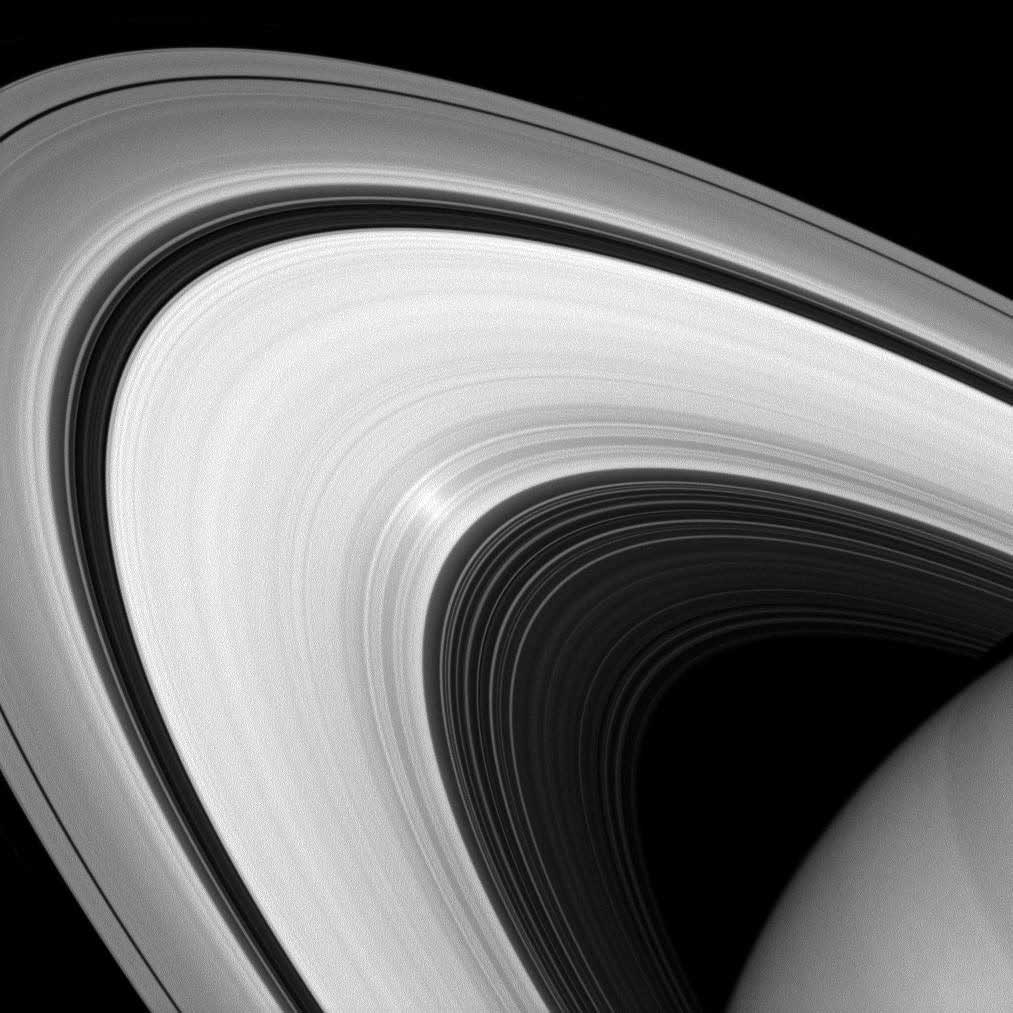

It wasn’t a steady dip, either. The star would fade, then brighten, then fade again, in a way that made no sense at all. When Mamajek and his group stumbled on the data in 2010, he says, “I took a printout of the light curve, put it on the wall, and stared at it for a week.” Crazy as it seemed, the most plausible explanation was a giant ring system with gaps like Saturn’s that let more or less light through at different times during the passage. “It’s the same indirect way the rings of Uranus were discovered in 1977,” he says.

See the Most Beautiful Space Photos of 2014

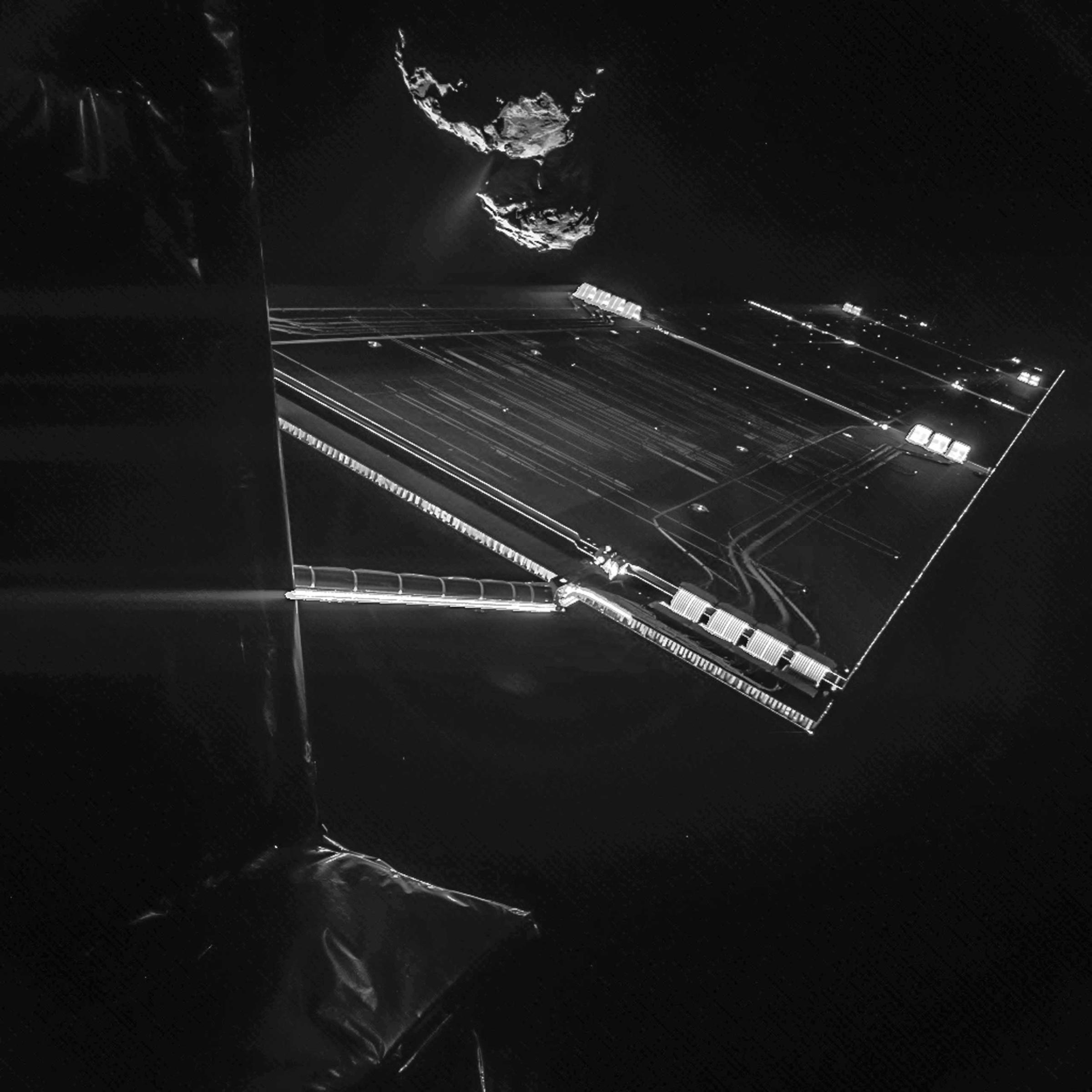

The planet itself doesn’t show up in the observations, but that could be explained if the ring system is slightly off-center as it moves in front of the star. You can see how this works in an animation put together by Mamajek’s collaborator Matthew Kenworthy, of the University of Leiden, in the Netherlands.

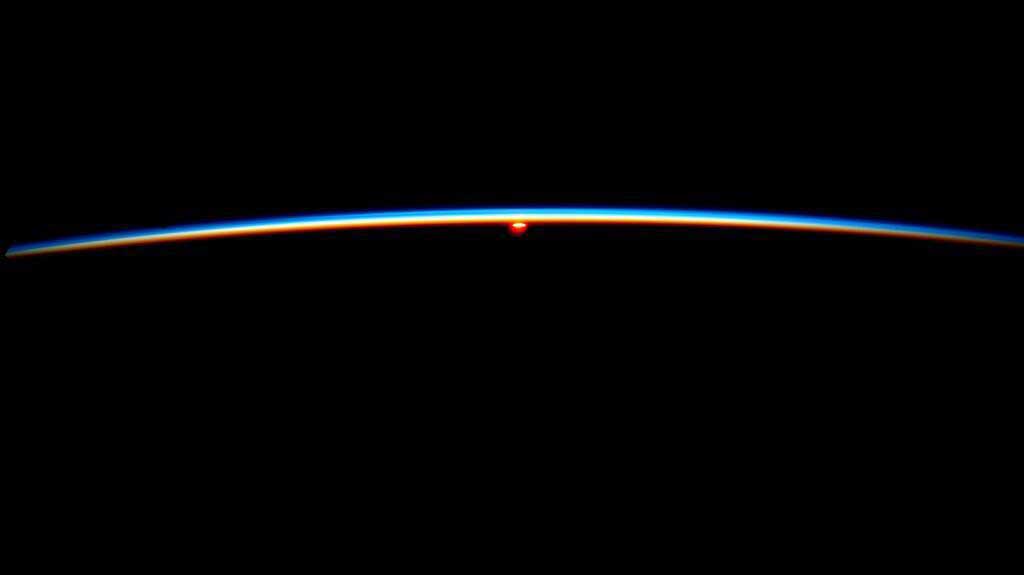

The star which the new planet orbits is thought to be very young—about 16 million years, compared with our own Solar System’s 4.6 billion. If the scientists are right about what they’re seeing, the mammoth ring system will get smaller over time as the outer bands condense into moons. “That’s what you see in [our] Solar System,” says Kenworthy. “You have rings tucked in close to the planets and moons further out. So presumably we’re seeing the intermediate step.”

It all seems familiar, except for the ring system’s size, which is unprecedented—and which is the reason other astronomers are waiting to be convinced. “I agree with the authors that it’s appropriate to consider an interpretation based on rings,” says Eric Ford, an expert on exoplanets at Penn State. The idea that the outer parts would condense into moons relatively quickly, however, means that we’re seeing the rings at their full extent during a very narrow window of existence—the sort of coincidence that scientists don’t love to see. “Whenever your explanation involves catching something during a phase that won’t last very long,” Ford says, “it’s a little concerning.”

MORE Cousins of Earth Found Deep in Space

Much of the doubt could be erased if astronomers could see the rings pass by again on another orbit around the star. Unfortunately, that hasn’t happened: they’ve got only the single passage back in 2007, meaning the exoplanet is on a relatively long orbit. “We think it’s at least ten or 15 years,” says Kenworthy.

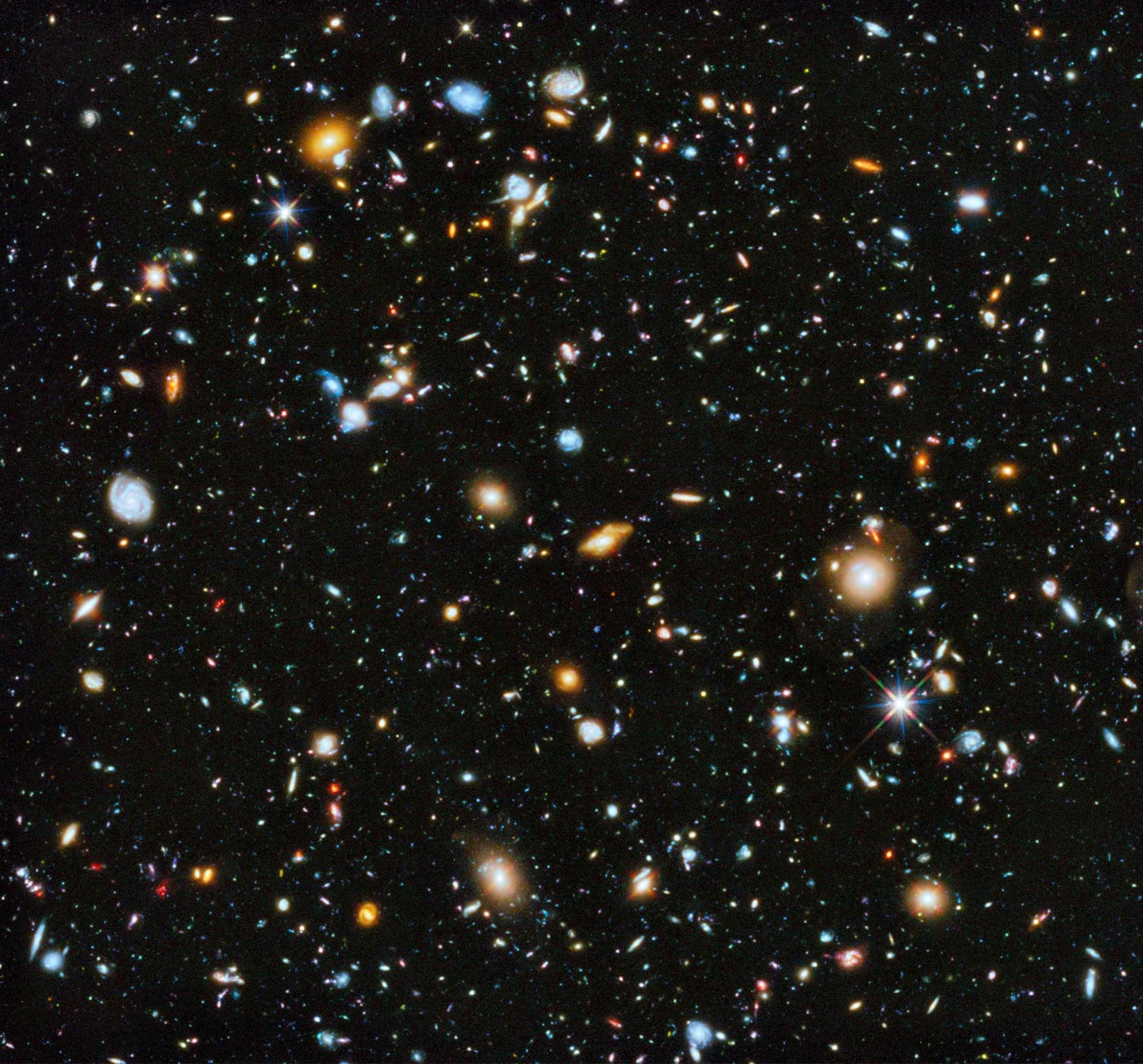

They don’t know for sure, though, and since it’s tough to keep big telescopes aimed at this one star hoping for another passage, the astronomers have recruited members of the high-end amateur group, the American Association of Variable Star Observers, to monitor the situation. They’re also going back through digitized versions of old images from observatories around the world, looking for evidence of other stars that faded mysteriously for a while without explanation. “Now that we know what we’re looking for,” Mamajek says, “we might find that there are lots of them out there.”

They might, that is, if they’re really seeing rings. “I keep telling people, ‘if you can think of a better explanation, please let me know,'” Mamajek says, and he means it. So far, he has no takers. “The signal is very strong,” says Harvard’s David Kipping, who is doing his own search for exomoons, “and its difficult to believe the instrument could misbehave on such a huge scale. I think many of us find the signal interesting,” he says. That, by itself, is enough to keep the astronomy community looking.

Read next: SpaceX, Boeing on Track to Get Astronauts into Space by 2017

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com