In 1994, eight black and four white jurors found 74-year-old white supremacist and long-time Klan member Byron De La Beckwith guilty of first-degree murder in the 1963 killing of civil rights activist and U.S. Army veteran, Medgar Evers. De La Beckwith had been tried decades earlier for the infamous and gutless crime—he shot Evers in the back, with a rifle, as the 37-year-old father stood in the driveway of his Jackson, Miss., home—but two trials ended in hung juries.

When De La Beckwith was finally held accountable for the assassination on this day in 1994, Evers’ widow Myrlie, who had fought for justice for her husband for more than 30 years, felt she might finally be free of the anger and hate she had borne for so long.

Her words upon hearing the verdict? “Yes, Medgar!”

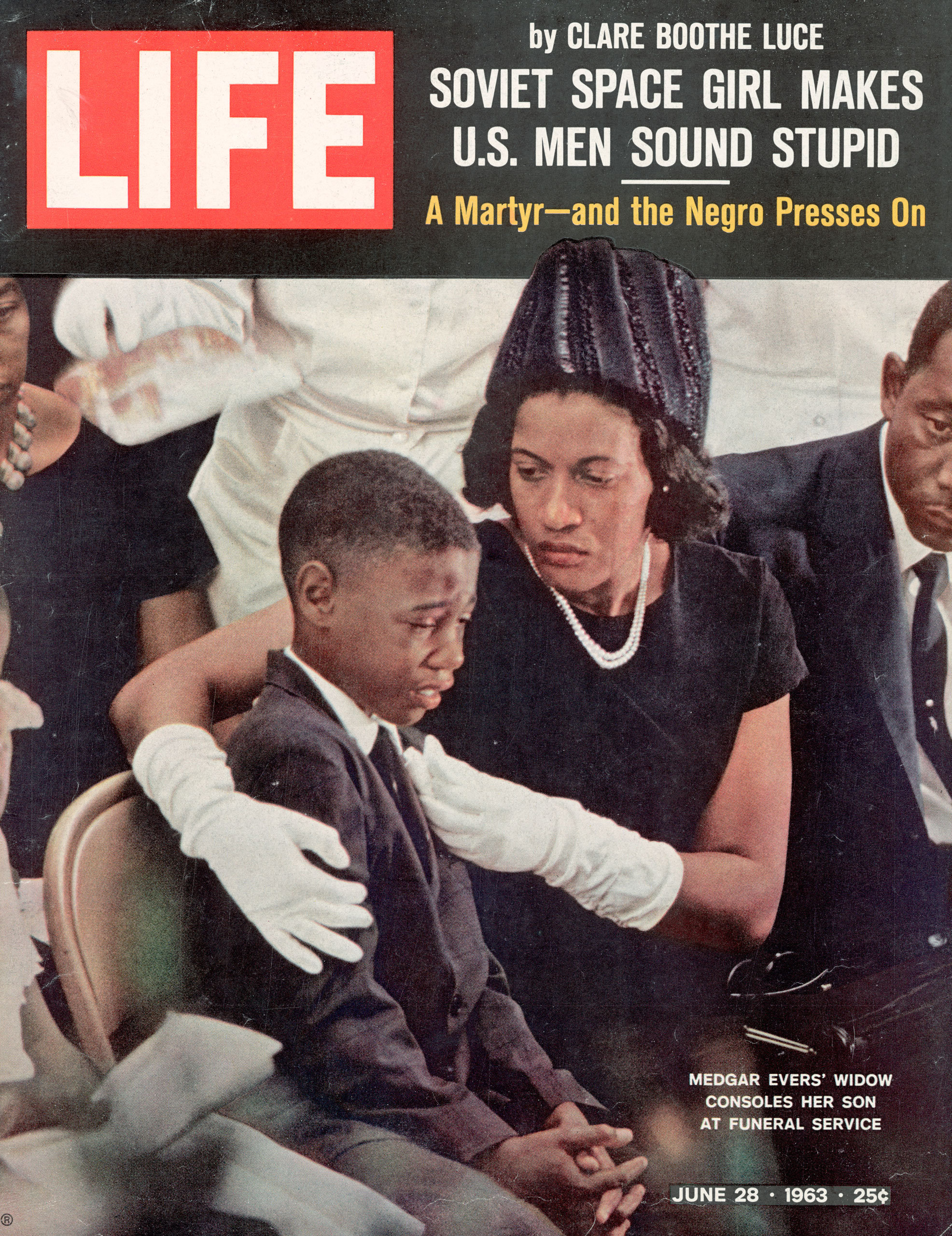

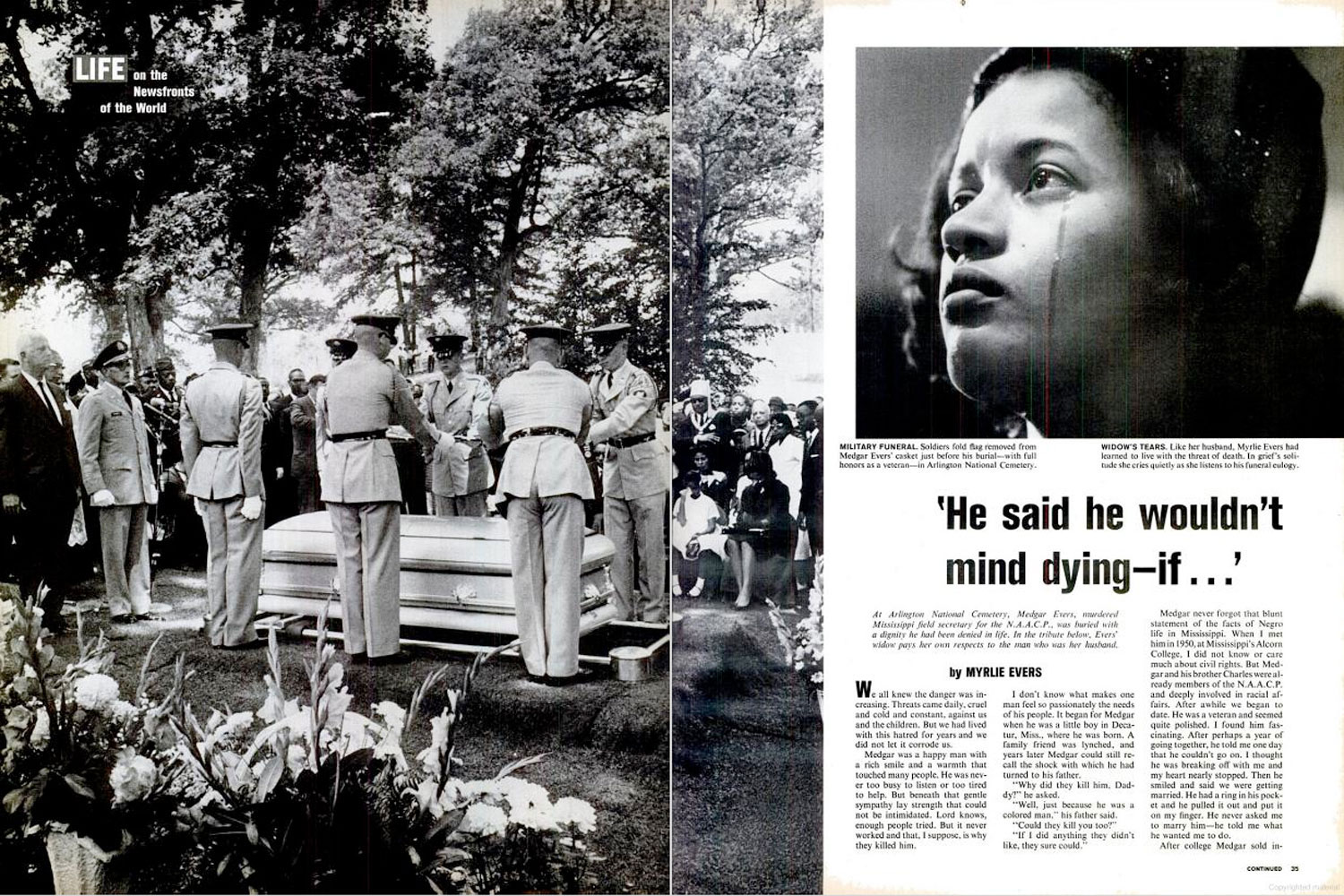

Here, LIFE.com presents a series of photographs by John Loengard—including one that remains among the most stirring of the Civil Rights era: a portrait of a dignified, deeply grieving Myrlie Evers comforting her weeping son, Darrell Kenyatta, at Evers’ funeral.

[MORE: A multimedia tribute to MLK and the 1963 March on Washington, “One Dream”]

All these years later, it remains a grimly fascinating exercise to revisit the coverage of Evers’ death. The domestic terrorism that would, in some ways, define the era—the murders of JFK, Malcolm X, Bobby Kennedy, MLK and others—had not yet reared above the horizon, and had not yet stunned and saddened the country and the world. So the daylight killing of a man of Evers’ stature and significance was—for people of conscience, anyway—an especially appalling crime.

In its June 28, 1963, issue, LIFE confronted the assassination with a combination of scorn (for the Klan and for white supremacists in general), anger (at the waste of such a life as Evers’) and an occasionally sardonic venom.

Though the name of Medgar Evers’ assassin remains unknown, not so the responsibility for his death. It may be found in the most recent report of the Mississippi Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Made up of Mississippians, 6 white and 3 Negro, this committee professed shock at its own findings and said “the people of Mississippi are largely unaware of the extent of the problem of illegal violence. They found that “in all important areas of citizenship a Negro in Mississippi receives substantially less than his due consideration as an American and as a Mississippian.” [Throughout his life] a Negro is treated with a “pernicious indifference” from the white man. Nor is this just a private caste system; it is enforced, legally and illegally, by the state and local governments. The committee found an “alarming number” of cases of police brutality. Its investigations were obstructed, not aided, by state officials.

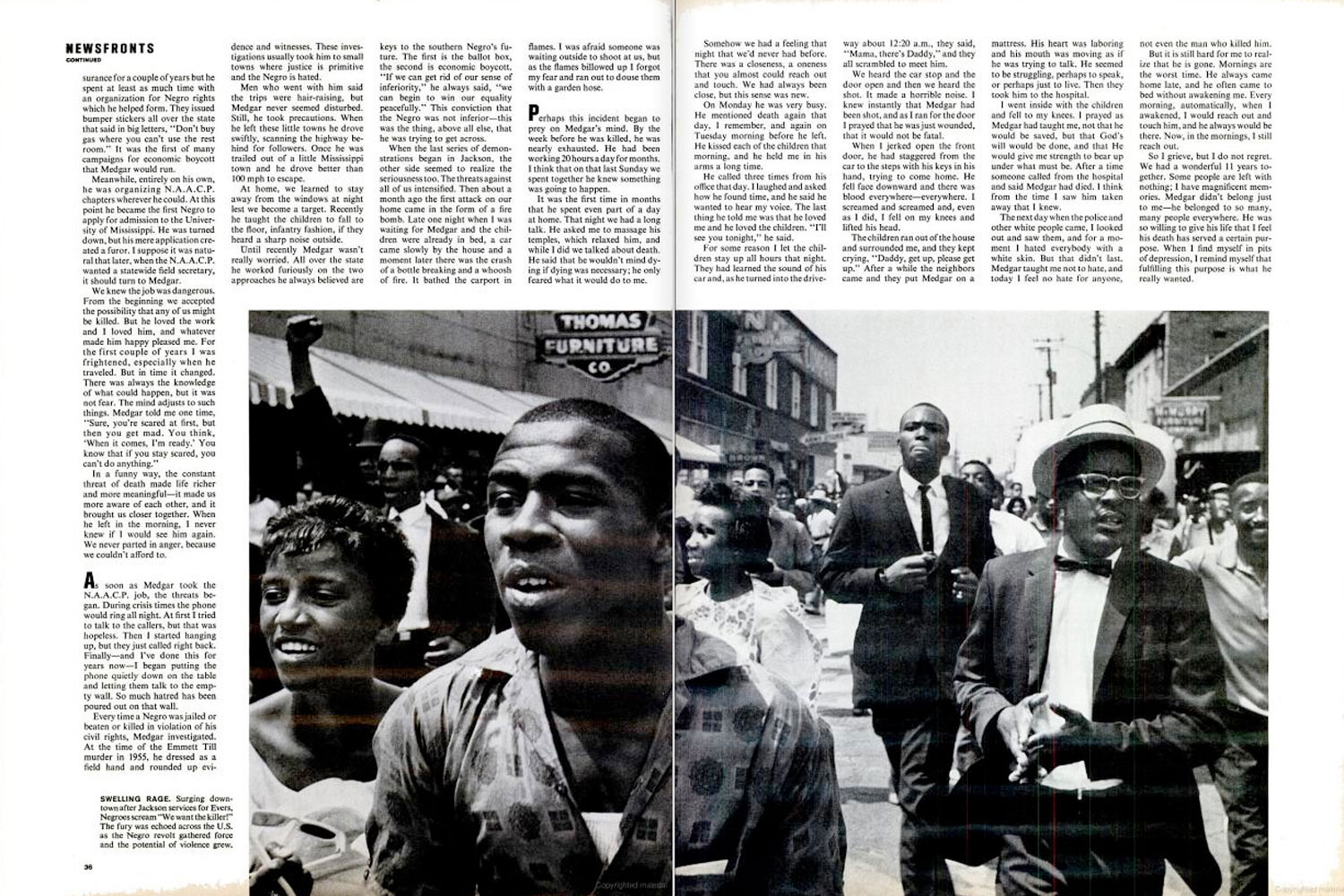

The events surrounding Evers’ death were like a lurid appendix to this report. After his murder the Jackson cops arrested some 350 Negro demonstrators under a parade-permit injunction, including ministers marching in pairs and handfuls of children bearing small American flags. [Jackson cops], with rifles, police dogs and flailing clubs, had to break up the singing mob that grew out of Evers’ funeral procession.

Mayor [Allen] Thompson calls Jackson “the closest place to heaven there is.” Like the governor and most of the political establishment in Jackson, he belongs to the (white) Citizens Council and says with them, “It’s going to be like this the rest of our lives. ” Their only worry is “outside agitators.”

Agitator Evers was a lifelong Mississippian. So, in all likelihood, was the man who shot him. [Note: De La Beckwith was a native Californian who had, indeed, lived most of his life in Mississippi. — Ed.] The Mississippi system breeds its own violence, which the NAACP has been trying to retrain.

On his way back from the funeral [diplomat, educator and Nobel Peace Prize laureate] Ralph Bunche wrote: “Had there been any conscience or sense of decency among the white citizens of Jackson, they would have flocked to the funeral service for Medgar Evers as a mild expression of their shame over the outrage for which they and Jackson must bear responsibility. They did not come. One must conclude that white Jackson of today has the morality of the jungle.” That is too sweeping, since there are many white moderates in Jackson. But when are they going to make themselves heard?

In the same issue, LIFE published a powerful tribute to Evers by his widow, Myrlie. “We all knew the danger was increasing,” she wrote. “Threats came daily, cruel and cold and constant, against us and the children. But we had lived with this hatred for years and we did not let it corrode us.” (See the page spreads from Myrlie Evers’ tribute in the gallery above.)

Medgar Evers is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1970 the City University of New York established Medgar Evers College in his name. His daughter, Reena, his youngest child, James, and his widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams (she married again in 1976) are still alive. His oldest son, Darrell, died of cancer in 2001; he was 47.

Byron De La Beckwith—who in the 1970s served three years in prison for transporting explosives—died at the University of Mississippi Medical Center while serving a life sentence for Evers’ murder. He was 80 years old.

Today, the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, is Harvey Johnson, an African American and proud native Mississippian.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com