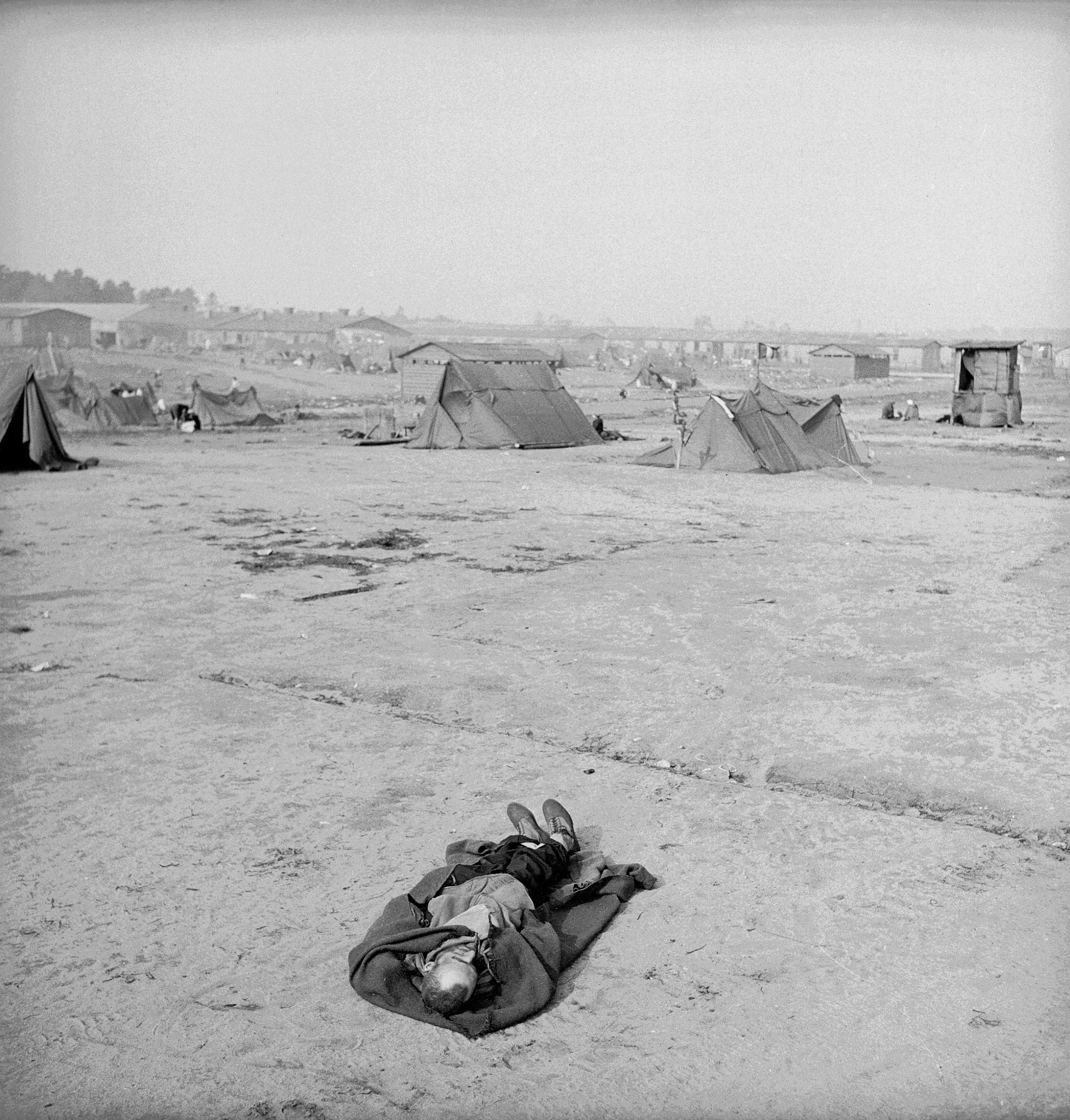

Compared to the appalling number of men, women and children killed at the Nazi extermination camps—places like Sobibor, Chelmno, Treblinka and others where, cumulatively, millions perished—the death toll at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northwest Germany was (a horrible thing to say!) relatively small. More than a million people were killed at Auschwitz-Birkenau alone; at Belsen, by most estimates, fewer than 100,000 died—from starvation and disease (typhus, for example), as well as outright slaughter.

But in the spring of 1945, photographs and eyewitness accounts from the liberation of camps like Bergen-Belsen afforded the disbelieving world outside of Europe its first glimpse into the abyss of Nazi depravity. All these years later, after countless reports, books, oral histories and documentary films have constructed a terrifyingly clear picture of the Third Reich’s vast machinery of murder, it’s difficult to grasp just how shocking these first revelations really were. The most horrific rumors about what was happening to the Jews and millions of other “undesirables—Catholics, pacifists, homosexuals, Slavs—in Nazi-occupied lands paled before the reality revealed by the liberation of the camps.

Here, seven decades after the April 1945 liberation of Bergen-Belsen by British troops, LIFE.com presents a series of photographs made at the camp by the great George Rodger (later a founding Magnum member). In an issue of LIFE published a few weeks later, in which several of the pictures in this gallery first appeared, the magazine told its readers of a “barbarism that reaches the low point of human degradation.”

Last week the jubilance of impending victory was sobered by the grim facts of the atrocities which the Allied troops were uncovering all over Germany. For 12 years since the Nazis seized power, American have heard charges of German brutality. Made skeptical by World War I “atrocity propaganda,” many people refused to put much faith in stories about the inhuman Nazi treatment of prisoners.

With the armies in Germany were four LIFE photographers. . . . The things [their photos] show are horrible. They are printed for the reason stated seven years ago when, in publishing early pictures of war’s death and destruction in Spain and China, LIFE stated, “Dead men will have indeed died in vain if live men refuse to look at them.”

In Rodger’s own typed picture captions, meanwhile, dated April 20, 1945, the photographer detailed what he had witnessed when he accompanied the British 11th Armoured Division (the fabled “Black Bull”) into the camp just days earlier. Somehow, the stark, almost telegraphic language of the notes carries more power—more immediacy—and are thus more terrifying than so many of the passionate, outraged articles and editorials that appeared in newspapers and on the radio in the weeks and months to come. Here are just a few examples:

Ukrainian women cooking a meal on a refuse dump in the camp. For fuel for their fire they used the ragged clothing torn from corpses. They are boiling pine needles and roots to form a sort of soup.

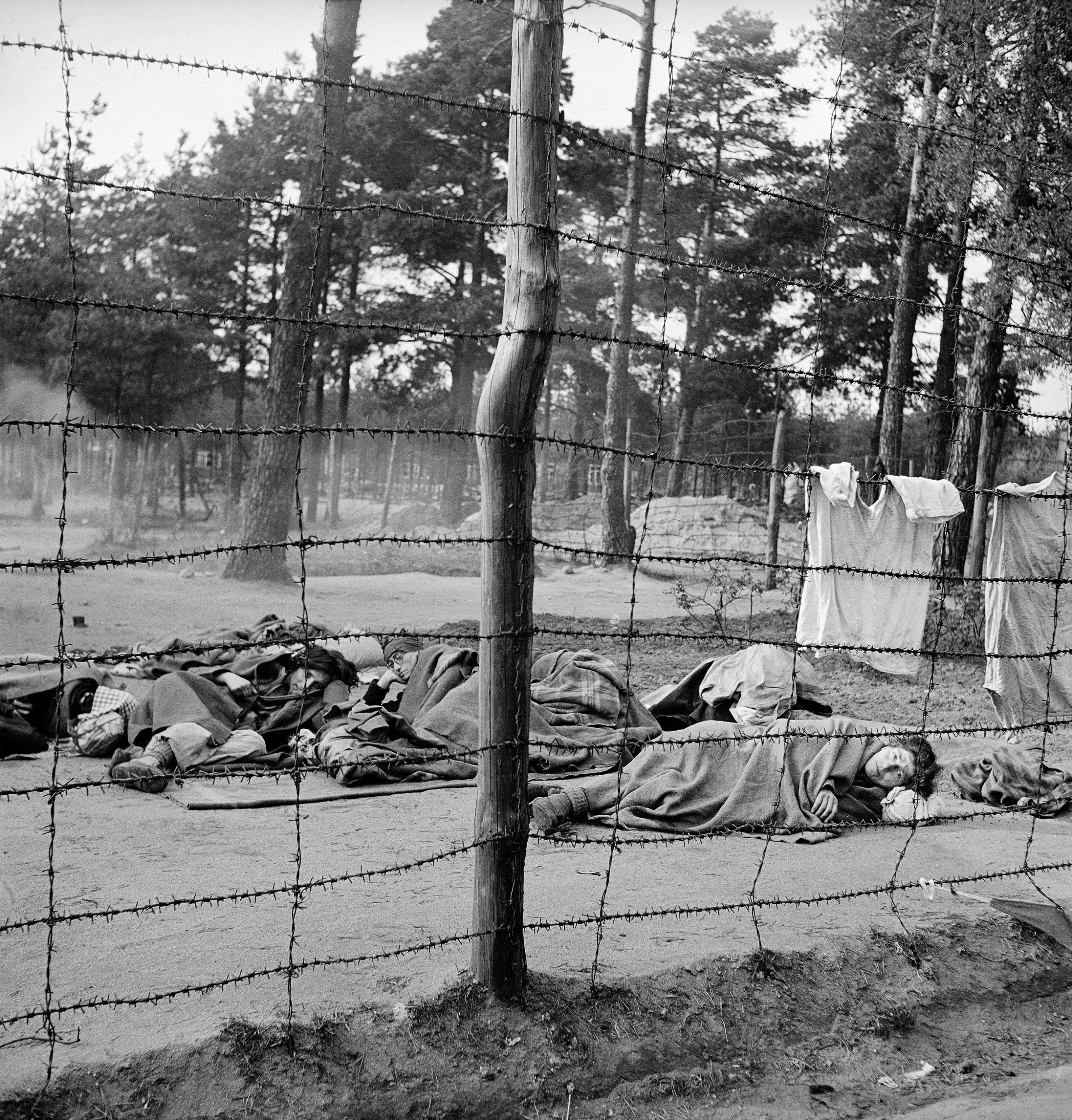

There must be about 5,000 bodies in this grave. The former SS guards—both women and men—are made to collect them. . . . These girls, all between 20 and 25, were even worse than the men. They were more cruel. Authentic stories are told of how these [women] tied living people to the corpses and burned them alive.

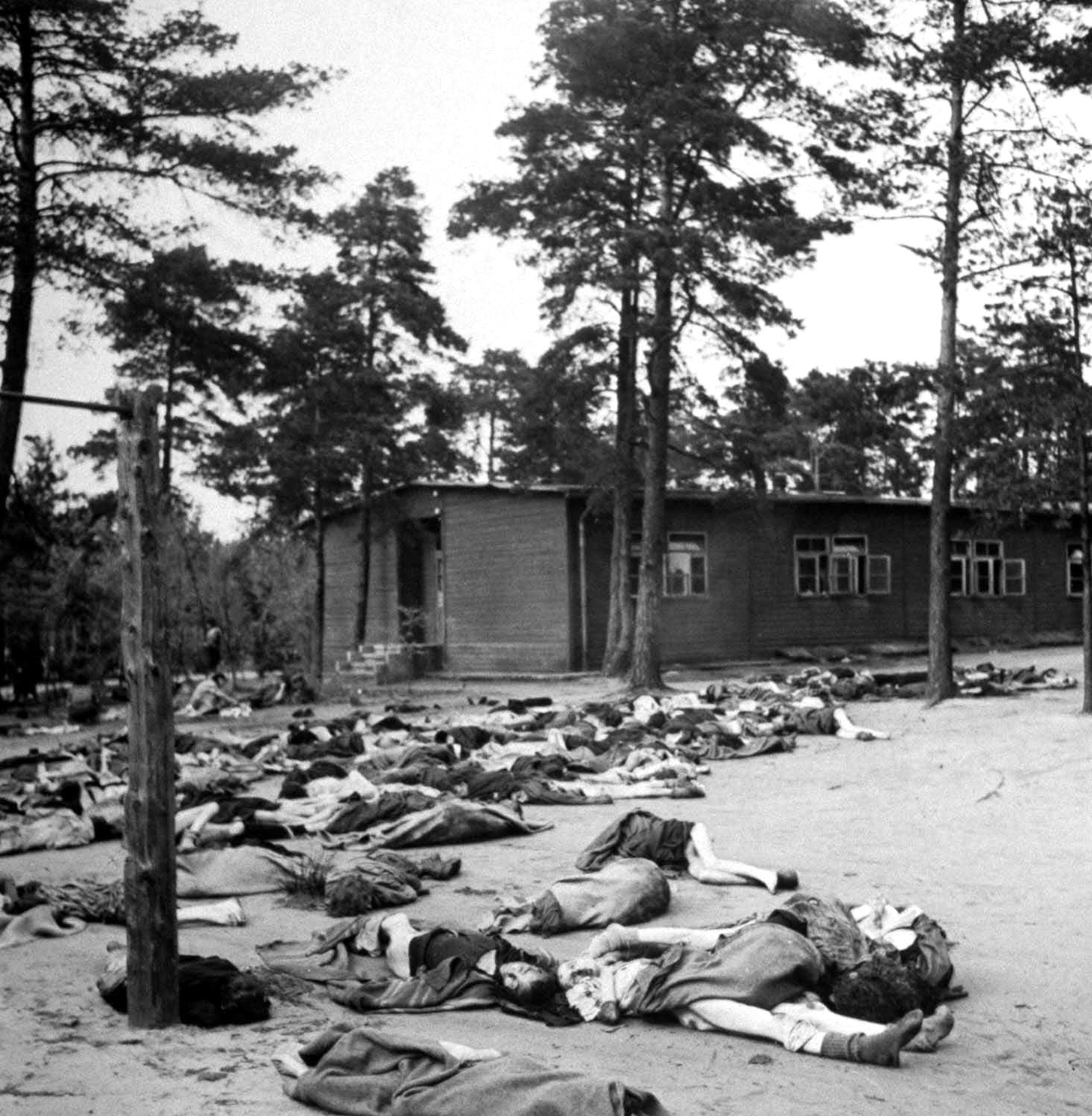

SS girls and men working in the mass grave and unloading the dead from trucks. These girls seem to be completely indifferent to what they are doing . . . [but] the former tough SS men crack up under . . . the strain of continually handling the bodies of those they helped to kill.

This man was talking to me when he fell dead beside me.

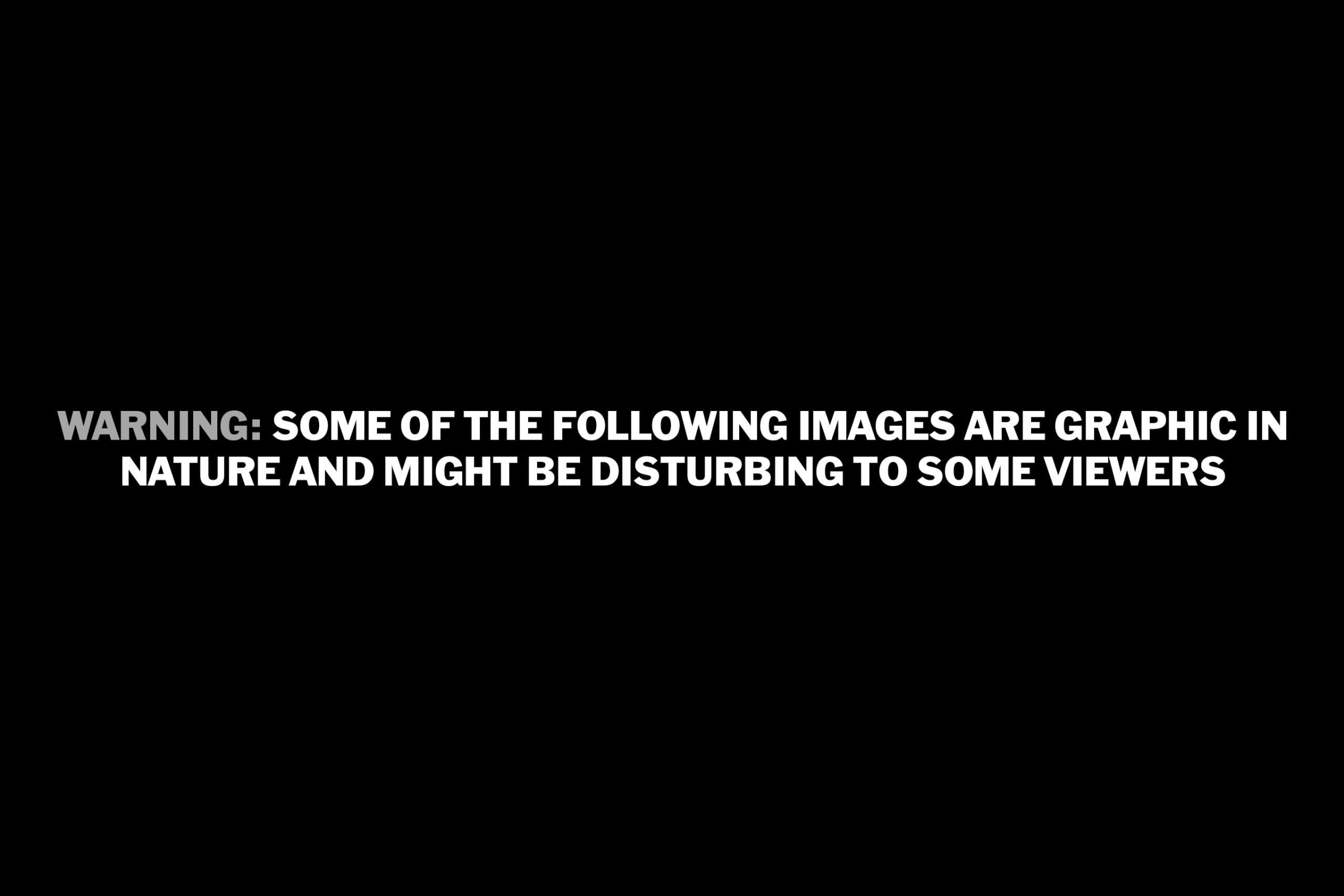

Women dying under the trees.

Indelibly scarred by the savagery and suffering he confronted during World War II—in England during the Blitz; in war-torn Southeast Asia and Europe; and, especially, in Bergen-Belsen—George Rodger did not work as a war photographer again. He did, however, continue to travel and photograph around the world in the decades after the war—particularly in Africa, where he made some of his most celebrated pictures.

By the time of his death in 1995, at the age of 87, Rodger was acknowledged as one of the 20th century’s indispensable photojournalists, and one of its greatest witnesses.

Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com