As Tennyson might have written, if he lived in 2013 and wasn’t a very good poet, “in the spring, and summer, and fall and winter, one’s fancy turns to thoughts of automobiles.”

There’s a lot to be said, in other words, for the romance of the open road.

And for as long as there have been cars, there have been men and women who have felt the need to alter, improve, manipulate—in short, to trick out their vehicles with accouterments and ornamentation that the manufacturer did not feel compelled to include in even its most crazily deluxe models. For some, these additional touches might be spinning hubcaps. For others, it might be furry dice hanging from the rear-view mirror, or animal-print upholstery, or flames painted on the hood.

For the braver among us, it’s a hydraulic system that helps a chopped ’65 Impala hop around like garlic in a hot skillet. But whatever the augmentation, the aim is always the same: to personalize a ride. To make it stand out. To make it one’s own.

And then there was Louie Mattar, who turned his 1947 Cadillac into a how-to guide for four-wheeled DIYers everywhere. As LIFE told its readers in a March 1952 article, “A Car That has Everything,” Mattar was “a San Diego garage owner with a big imagination.”

When he bought a brand new Cadillac four years ago, the extra equipment his dealer offered was not enough and Mattar started to add a weird assortment of things that other motorists can only dream of.

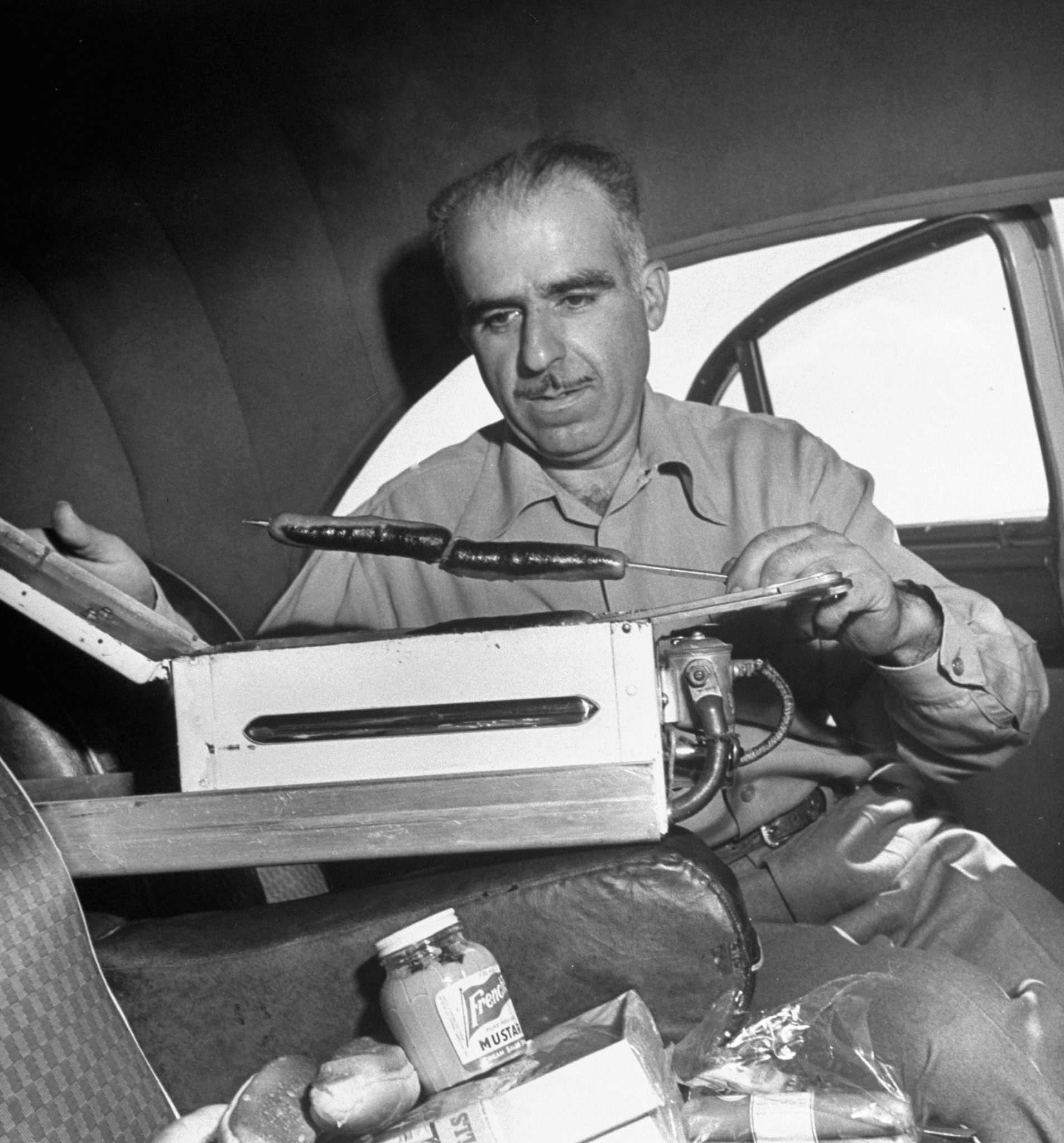

Doing most of the work himself, he put in a shower, coiling the pipes from his 50-gallon water tanks around the exhaust manifold for the hot water. A pumping system was crammed under the hood. Next to the taillight went a drinking fountain and under the dashboard a tape recorder and a bar with spigots for whisky, water and soda. In the back seat he put a washing machine, a stove and even included a kitchen sink. All this took four years to do and cost Mattar better than $14,000.

To the average motorist most of Mattar’s optional equipment may not seem a necessity for the family car. But Mattar does have one gadget that should appeal to any red-blooded American driver. Next to the driver is a microphone attached to a loudspeaker artfully concealed under the hood. Whenever he feels like it, Mattar can give helpful suggestions to reckless pedestrians or delivers commentaries on the driving habits of less well-equipped motorists.

One additional note: Later that year, in Sept. 1952, Mattar’s ultra-tricked-out Caddy set a world endurance non-stop record (since eclipsed) when three drivers, working in shifts, traveled round-trip from San Diego to New York and back—6,300 miles—in one week. It later traveled—virtually non-stop, due to Mattar’s innovations that allowed it to refuel while driving, etc.—from Anchorage, Alaska, to Mexico City. Today, Mattar’s wild ride is on display at the San Diego Automotive Museum in Balboa Park.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com