No occasion in New Delhi’s official calendar is as laden with nationalist imagery as the celebration, every Jan. 26, to mark the day in 1950 when India’s constitution came into force. Tanks, missiles and thousands of soldiers, along with elaborate floats representing the country’s states, roll down Rajpath, the Indian capital’s broadest avenue, to commemorate the milestone in a grand, Soviet-style parade. Which is why, this year, when U.S. President Barack Obama takes his place next to India’s leaders to witness the pageantry, there will be no mistaking the political symbolism.

Obama, who is due to arrive here this weekend, will be the first American leader to attend the parade, and his presence on Rajpath alongside the Indian President Pranab Mukherjee — the country’s ceremonial head of state — and Prime Minister Narendra Modi will send out a clear message that the relationship between the two countries “is now accorded a special status that’s a bump up from the past,” says Milan Vaishnav, an analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

It will also underscore a rapid shift in U.S.-India ties, which descended into an angry diplomatic row involving Devyani Khobragade, India’s deputy consul general in New York City, in late 2013. Accused of visa fraud and underpaying her housekeeper, Khobragade was handcuffed and strip-searched by U.S. marshals, triggering furious protests from New Delhi. India retaliated by yanking away various privileges enjoyed by American diplomats and removing security barriers from around the U.S. embassy in New Delhi’s diplomatic quarter. And then in March, as India’s political class limbered up for national elections, the fracas was seen by many as a factor behind the departure of Nancy Powell as Washington’s top envoy to the country. (U.S. officials denied the link.)

“The Indians were outraged, it was a big thing in the media, and the relationship was put on hold,” says Robert Hathaway, a public-policy scholar and former director of the Asia program at the Wilson Center. “The contrast of last year to this year is perhaps the most remarkable thing about this visit.”

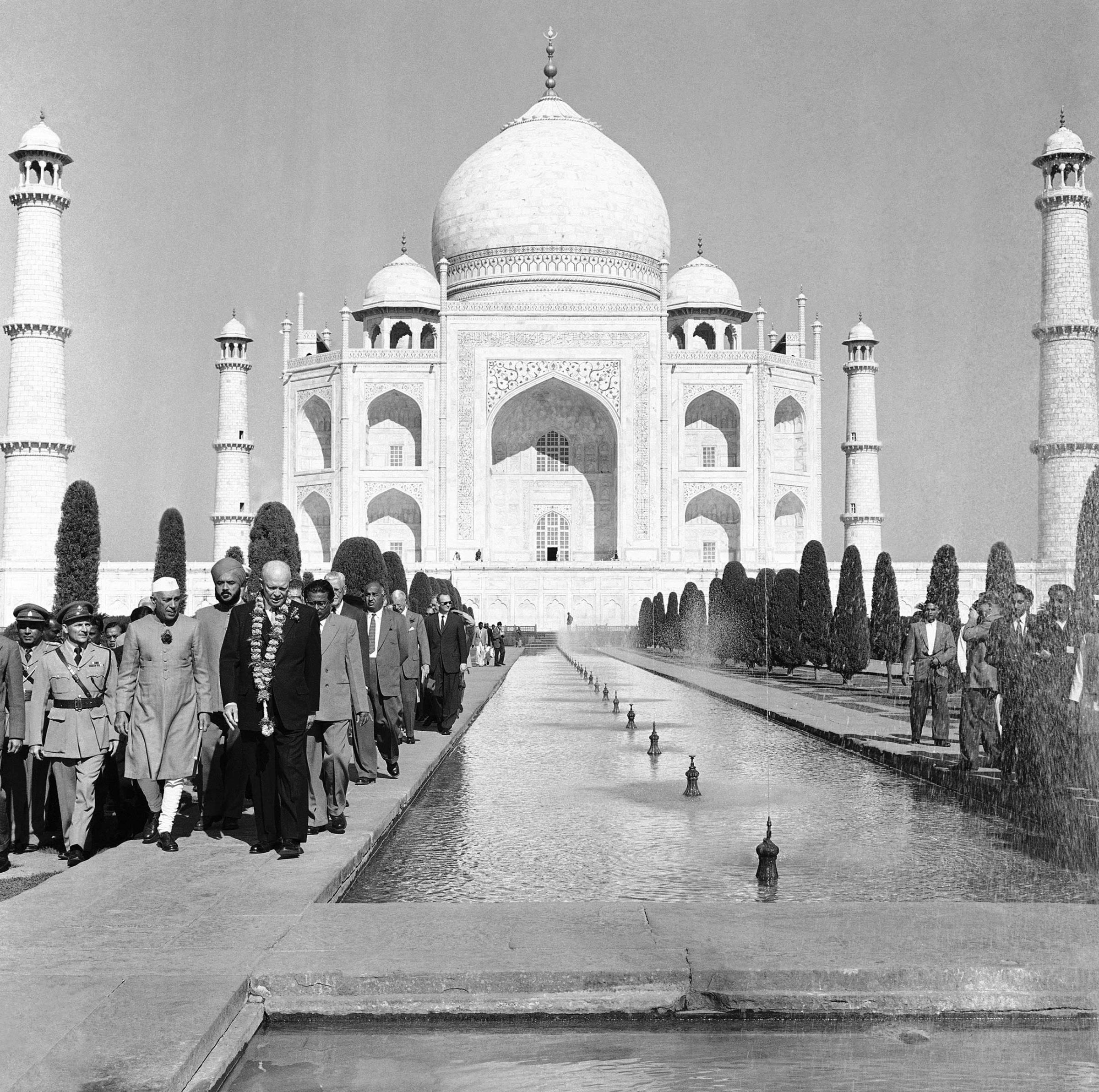

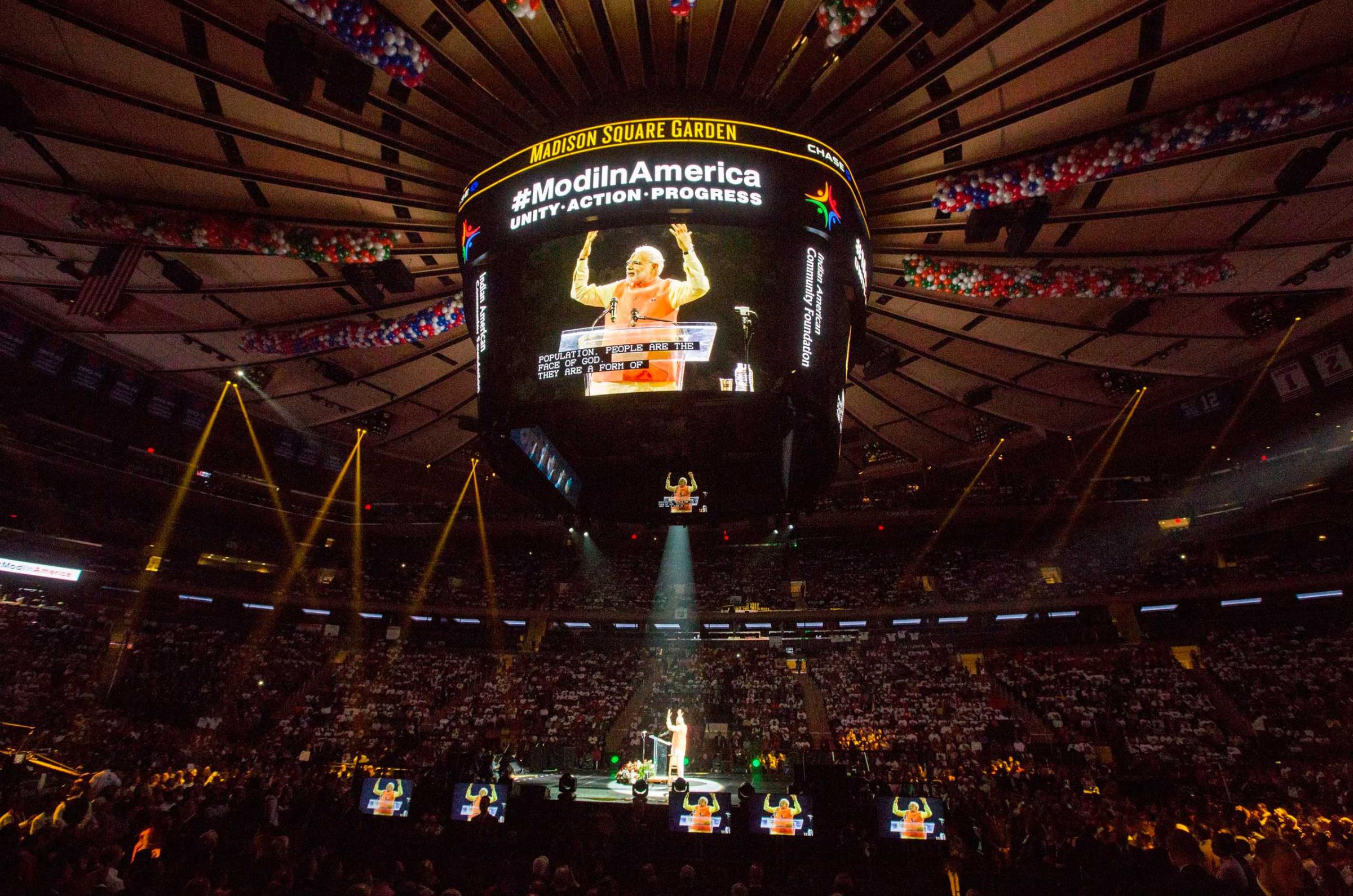

See The History of US—India Relations in 12 Photos

Powell has since been replaced by Richard Verma, the first Indian-American U.S. ambassador to New Delhi. And Modi, who led his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party to victory in last year’s elections with promises to revive India’s flagging economy, has already called in at the White House during a trip to the U.S. Modi’s visit also put to rest any concerns about his feelings toward a country that denied him a visa in 2005. Citing the bloody sectarian rioting that shook the western Indian state of Gujarat in 2002, when Modi was chief minister, the U.S. blocked the Indian leader from visiting New York. But all was forgotten in September, when the newly installed Prime Minister Modi visited Washington at the invitation of the American President. Plans for Obama—who this weekend will also become the first sitting U.S. leader to visit India twice, following an earlier trip in 2010—to attend the Jan. 26 parade were put in motion shortly thereafter.

“We did expect that [Obama] would visit again in his second term, especially after he had reached out to [Modi] and the Indian Prime Minister had reciprocated — but we didn’t expect that it would be so soon,” says Tanvi Madan, the director of the India project at the Brookings Institution. “I think both want to take advantage of the momentum that they built with the last visit.”

To buttress that momentum and bilateral bonhomie, officials on both sides are working to ensure that the coming meeting between the President and the Prime Minister yields more than just another handshake. The focus is on “deliverables” — jargon for deals between the two governments that could be announced when Obama greets Modi. “Both sides will clearly have a full agenda of issues that they want to come to some meeting of minds about,” says Hathaway. “They will succeed in some respects but I certainly don’t expect any huge breakthroughs.”

The American side’s agenda became clearer earlier this month, when U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry flew to India to attend an economic summit in Gujarat, highlighting four burning issues when the two leaders sit down together: cooperation in the civil nuclear sector, climate change, defense and security, and economic ties. The last item on the list will likely be one of the first to come up, says Hathaway, as investors in India and beyond wait to see if the Modi government can deliver on its promise to boost the country’s flagging economy. “They will talk about how the United States can help Modi achieve his domestic economic agenda,” he explains. “They’ll talk about trade, they’ll certainly talk about investments.”

But whether these economic talks bear fruit might ultimately hinge on what happens in the weeks and months after Obama flies home. The Modi government’s first budget, put together less than two months after the new administration took office last May, was widely judged to be a disappointment. Attention now is focused on whether its second budget, expected at the end of February, can usher in the reforms economists say are needed to spur growth and attract investors.

On climate change, there’s little prospect of the kind of agreement reached between the U.S. and China last year, when Beijing for the first time agreed to cap its carbon emissions. Todd Stern, the U.S. special envoy for climate change, nipped any speculation in the bud last month when he said no such pact was in the works with New Delhi. Instead, the emphasis during the Obama visit will be on securing India’s backing for a global climate deal at a planned international summit in Paris at the end of the year. As the world’s third largest carbon polluter, India’s agreement is seen as key to securing an international accord to cut emissions.

The two countries are also trying to break a long-standing impasse over an Indian law that makes equipment suppliers liable for accidents at nuclear plants, in contrast to international rules that place the burden of damages on plant operators. Critics say the legislation has blocked American suppliers from the Indian energy sector despite a landmark civilian nuclear-cooperation deal between the two governments in 2008. While the prospects for a resolution in coming days remains uncertain, Indian and American officials reportedly plan to meet Wednesday to see if they can hammer out an accord in time for the President’s visit.

All of which leaves defense and security ties. Here, discussions between Obama and Modi are likely to range wide, from the U.S. troop withdrawal in Afghanistan and its implications for India’s security, to the recent skirmishes along the India-Pakistan border. Washington and New Delhi are also expected to renew a decade-old defense-cooperation pact that is set to expire this year. The big headline, though, would be a deal to jointly produce a new piece of defense hardware. Long talked about and far from assured next week, such an agreement would both underline the strength of U.S.-India ties and dovetail nicely with Modi’s campaign to boost Indian manufacturing.

“Even if it’s something that’s relatively small, the symbolic effect could be quite positive,” says Vaishnav.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Rishi Iyengar at rishi.iyengar@timeasia.com