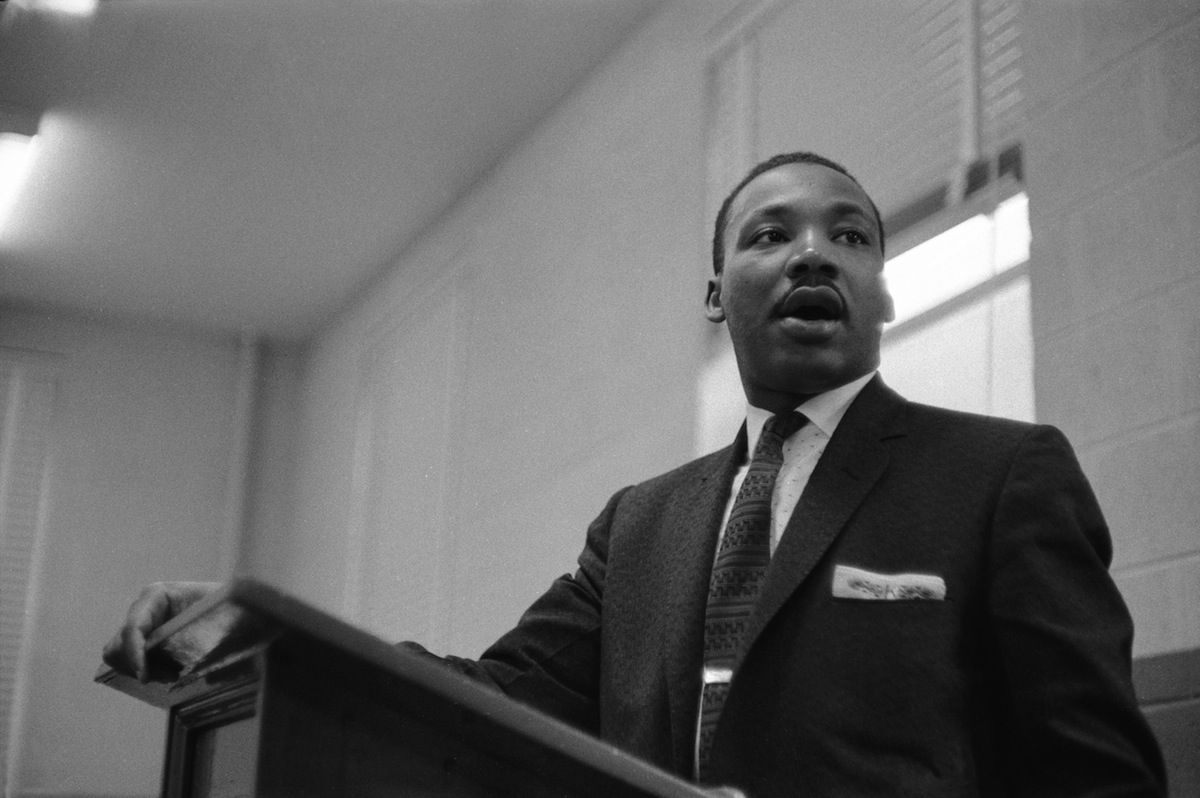

Before he was assassinated in Memphis in 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. led a movement that had won many victories, but the issues of justice and peace he fought for are still with us. What are some concrete ways to talk with kids about King and his legacy, not just on Martin Luther King Day, but in ongoing conversations?

Clayborne Carson, founding director of the King Institute, professor of history at Stanford University, and author of Martin’s Dream, suggests parents look at King’s childhood. The civil rights leader clearly describes the injustice he suffered in his autobiography: “For a long, long time I could not go swimming, until there was Negro YMCA. A Negro child in Atlanta could not go to any public park. I could not go to the so-called white schools. In many of the stores downtown, I couldn’t go to a lunch counter to buy a hamburger or a cup of coffee. … I remember seeing the Klan actually beat a Negro. I had passed spots where Negroes had been savagely lynched. All these things did something to my growing personality.”

King also recalls how his mother talked about these issues with him: “She taught me that I should feel a sense of “somebodiness” but that on the other hand I had to go out and face a system that stared me in the face every day saying you are “less than,” you are “not equal to.” … Then she said the words that almost every Negro hears before he can yet understand the injustice that makes them necessary: ‘You are as good as anyone.’”

Andrea McEvoy Spero, director of education at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Institute at Stanford University, suggests that parents can talk their own elementary age kids through the same issues by starting with a basic discussion of what’s fair and unfair, and what it means to be part of a community, with questions like, “What does it feel like to be excluded? What can I do to help other people feel included?”

By middle school, McEvoy Spero says, kids can wrestle with King’s statement that “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’” And parents can help kids answer that question not just by asking their kids, but by asking themselves, what they are doing for others. “Our young people are watching us,” she says.

In high school, kids are ready to “get into the complexity,” McEvoy Spero says: how to fight like King did to defeat the three interrelated evils of war, racism, and poverty. Older kids can start asking not just what they can do to help, but what they can do to create change. And they’re old enough to turn to King’s writings, like “The Drum Major Instinct,” or the famous “I Have A Dream” speech.

At any age, it’s important to help students remember that King wasn’t a legend, but a person, just like them. “If you put someone on a pedestal, they you can’t really be like them,” Carson says. “But if you realize that he was a human being just like the rest of us, who was caught up in a great movement and did extraordinary things, then people begin to understand that they can do extraordinary things, too.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com