On the third day of his trial, Ross Ulbricht looked calm for a man who could soon be sentenced to life in prison. The gangly 30-year-old’s parents, Lyn and Kirk, sat behind him in a wood-paneled courtroom fifteen stories above lower Manhattan last Thursday. During breaks in testimony, Ulbricht turned in his chair and smiled broadly at them from beneath a poof of brown hair. “Did you have a good lunch?” Lyn asked her son after a pause on the third day of proceedings. Ross grinned and shook his head. “I’ll tell you about it later.” Lunch in prison doesn’t usually come with an unadulterated endorsement.

Ulbricht, an Eagle Scout with a master’s degree in materials science and engineering who friends say is well-liked and sensitive, is facing grave charges. Fifteen months ago, he was arrested and accused of drug trafficking, computer hacking and running a criminal enterprise, among other charges. His case has become a flash point for Internet activists, who worry a conviction could deal a blow to free speech on the Internet.

Ulbricht’s arrest was the culmination of a two-year investigation into the seedy online bazaar Silk Road, where the narcotics-hungry could find drugs for sale in exchange for Bitcoin, a difficult-to-trace digital currency. Silk Road was controlled by a shadowy website administrator with the moniker Dread Pirate Roberts, who prosecutors say took home millions in commissions on more than $1 billion worth of drug deals and other transactions. Roberts also allegedly used the site to order the murders of six people.

The central question in this trial is whether Ulbricht is indeed the Dread Pirate Roberts. Government prosecutors say that’s the case; they want to send Ulbricht to prison for 20 years to life for his alleged crimes. But there’s more at stake here than charges against a single man: Open Internet activists, some of whom have donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Ulbricht’s defense, say his case is a matter of online freedom.

(Read more: What Was Silk Road? Refresh Your Memory as Ross Ulbricht Goes to Trial)

A closely-watched case

Traditionally, website operators have not been held liable for illegal activity carried out on their platforms. An appellate court decision gave the social network MySpace legal immunity in 2008, for instance, after an underage teenage girl was sexually assaulted by someone she met through the website. Activists, however, see Ulbricht’s trial as a landmark case, worrying that a conviction could stifle free speech on the Internet.

Last July, the judge on the case ruled that if Ulbricht created Silk Road as a drug trafficking haven as the government alleges, then he’s vulnerable to the narcotics conspiracy charges against him. But the defense argues Ulbricht only founded the site as an “economic experiment,” not as a narcotics ring—even if that’s what Silk Road became. If that argument holds up but Ulbricht is still found guilty of some charge or all charges, it could have a chilling effect on digital free speech.

“At what point are you liable for what happens on a site that you start?” says Hanni Fakhoury, an attorney for the non-profit Electronic Frontier Foundation who’s been watching the case as a neutral observer. “If the government indicted every time someone posted a prostitution ad on Craigslist, [Craigslist founder] Craig Newmark would be in prison all day.” While Fakhoury believes the case could have broader implications for how the government prosecutes website operators for their users’ behavior, he admits Silk Road is at “the far end of the spectrum” of normal Internet activity.

Then there’s the question of how federal agents investigated Silk Road. The defense, led by Joshua Dratel, an expert but somewhat rumpled attorney who has represented high-profile terror suspects and Guantanamo Bay detainees, says the government seized data from the site’s servers without a warrant.

The judge threw out the defense’s motion on those grounds, but the claim opened up the door to several important questions: How exactly did the feds find Silk Road’s servers? Were Ulbricht’s constitutional rights violated in the process? Less than a week and just one witness into the trial, it’s hard to tell how these questions will play out. But the testimony has so far been revelatory, unveiling a federal sting operation worthy of a blockbuster script.

(In the magazine: The Secret Web: Where Drugs, Porn and Murder Live Online)

How Ulbricht was busted

The government’s first witness was Department of Homeland Security investigator Jared Der-Yeghiayan. Der-Yeghiayan says he began looking into Silk Road in early 2012 after federal investigators noticed vendors were using the website to sell drugs. Der-Yeghiayan testified that he made more than 50 drug buys and logged thousands of hours on the website until it was shut down in October 2013.

By August 2013, Der-Yeghiayan managed to seize the account of a lead website administrator named Cirrus. He then used the account to communicate with Dread Pirate Roberts several times a week, with Roberts unaware “Cirrus” was now a government agent.

After Der-Yeghiayan took over Cirrus’ account in August 2013, he began reporting directly to Dread. Dread paid Der-Yeghiayan about $1,000 per week to manage Silk Road’s forums and user questions. The pair were cordial, often asking each other how they were doing. “Thank you for looking after the forums,” Dread told Der-Yeghiayan in one chat.

In another post, Dread addressed users’ criticism that he was taking a commission on each drug trade. Some users were calling it a “tax.” Dread objected to Silk Road being compared to the government, and instead called it a broker’s fee. Like any successful private enterprise, Dread said, Silk Road needed to support itself. “Do you think this site built itself? Do you have any idea of the risks?,” he said.

The Sting

In September 2013, an investigator on the case named Gary Alford told Der-Yeghiayan that a 29-year-old former University of Texas physics student named Ross Ulbricht appeared to be a “pretty good match” to Dread Pirate Roberts’ profile. The FBI got a warrant for Ulbricht’s arrest. By the end of that month, a team of agents set out for San Francisco, where Ulbricht lived under the name “Josh Terrey.”

According to Der-Yeghiayan’s testimony, plainclothes federal agents fanned out across San Francisco’s Glen Park neighborhood on the afternoon of Oct. 1, 2013, monitoring public places with free Wi-Fi access. The plan was to catch Ulbricht signed into Dred Pirate Roberts’ Silk Road account. That way, the government said, it could link Ulbricht the man with Dread the moniker.

At around 2:40 p.m., Der-Yeghiayan settled into Bello, a coffee shop near Ulbricht’s apartment, and logged into the Silk Road administrators’ chat. Dread Pirate Roberts was online briefly until 2:47 p.m. Just minutes after Dread signed off, federal agents saw Ulbricht leave his apartment and walk down the street in the direction of Bello, right where Der-Yeghiayan was still sitting. Der-Yeghiayan ducked out of Bello while the team watched as Ulbricht waited at a crosswalk 50 feet away before entering the shop.

Ulbricht left Bello almost immediately, apparently because it was too crowded. Ulbricht walked thirty feet down the street and disappeared into the Glen Park Branch Library. A few moments later, Dread Pirate Roberts signed on to Silk Road’s chat.

“hi,” [sic] typed Der-Yeghiayan into a chat with Dread, posing undercover as Cirrus. “are you there?” The goal, Der-Yeghiayan says, was to get Ulbricht to log on to Silk Road as Dread, proving the man and the moniker were one in the same.

“hey,” Dread responded.

“how are you doing?” said Der-Yeghiayan.

“i’m ok, you?” said Dread.

“good,” said Der-Yeghiayan. “can you check one of the flagged messages for me?”

“sure,” said Dread. “let me log in.”

It was a trap. Dread Pirate Roberts was now signed in to both the chat and the Silk Road website. FBI agents entered the library, snatched Ulbricht’s laptop and handcuffed him. Der-Yeghiayan walked up the stairs and inspected the computer. Ulbricht was signed in to Silk Road. It was Dread Pirate Roberts’ account.

Even a skilled defense attorney like Dratel would have trouble accounting for Ulbricht being caught red-handed. But Dratel has an explanation: Ulbricht was framed.

Yes, Ulbricht founded Silk Road 2011, Dratel said, but he quickly distanced himself from the online bazaar. Ulbricht never profited from the heroin, cocaine and ecstasy deals trafficked on its pages, Dratel said, and he certainly didn’t order the murders of six people. According to Dratel, Ulbricht was lured back to the website shortly before he was arrested in late 2013 by its then-administrator: Mark Karpeles, chief executive of the Japan-based Bitcoin exchange Mt. Gox, which allowed anyone to convert cash into Bitcoin.

“Our position is that [Karpeles] set up Mr. Ulbricht,” Dratel said in court.

Here’s the twist: Federal agents were ready to indict Karpeles for running Silk Road right up until September 2013, one month before they arrested Ulbricht. Even Der-Yeghiayan himself, after months of undercover drug buys, believed Karpeles was using Silk Road as leverage to drive up Bitcoin’s value.

Under questioning on Thursday, Der-Yeghiayan says he was ready to move on Karpeles. What happened? Dratel insinuated that Karpeles’ lawyer met with the feds and offered to give up the name of the real masterminds behind the Silk Road website. The court adjourned before his questioning ended. It’s not hard to see the defense’s argument here: Karpeles was about to get busted, so he trapped Ulbricht. Karpeles adamantly denies he was ever involved in Silk Road.

For now, the truth seems as elusive as it was to Der-Yeghiayan in June 2013, when in an email to federal agents about the identities of Silk Road users, he confessed he was clueless. “Sheesh, who’s on first?” Der-Yeghiayan said, according to testimony. It’s a sentiment the rest of the courtroom shares.

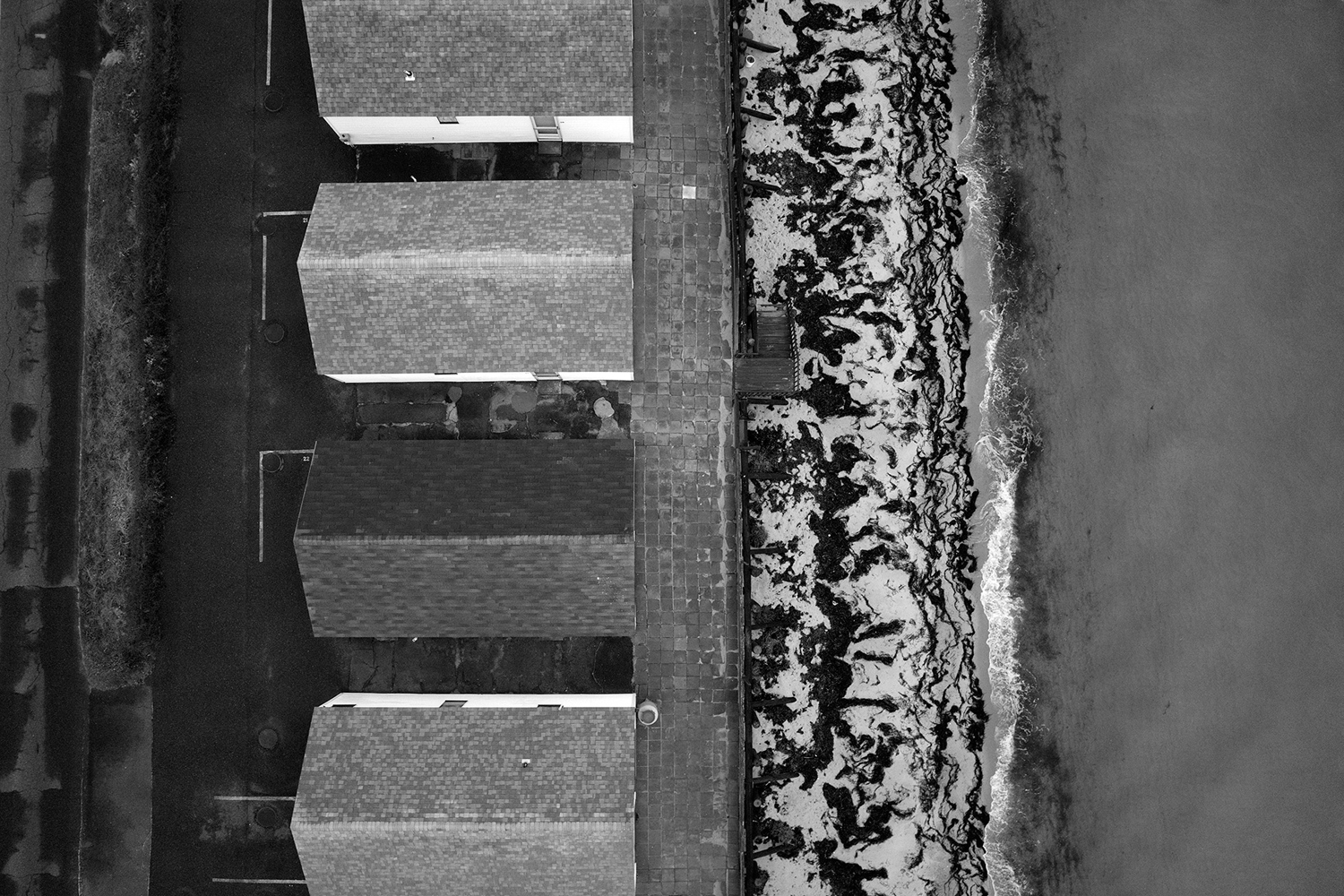

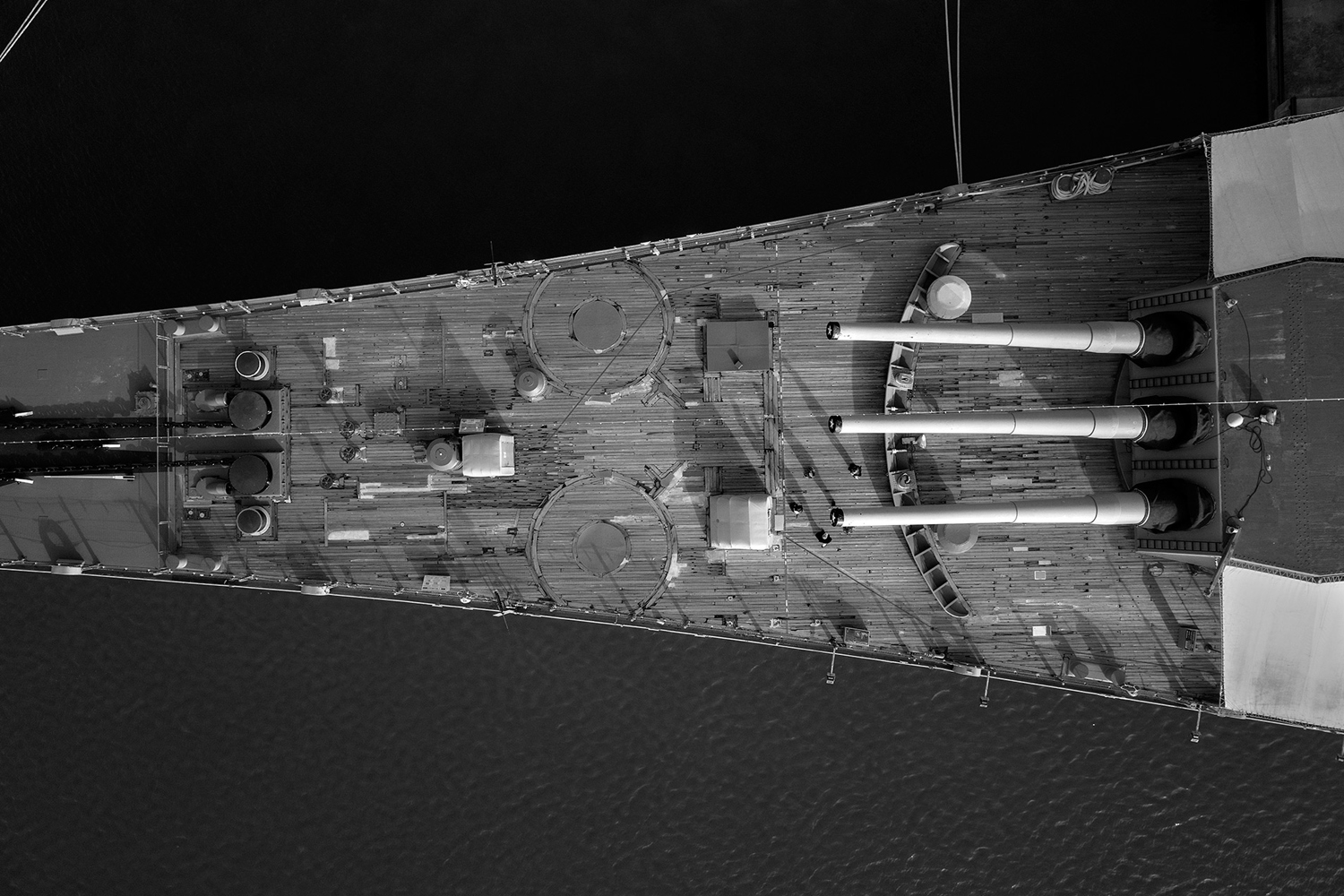

Drone Country: See America From Above

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com