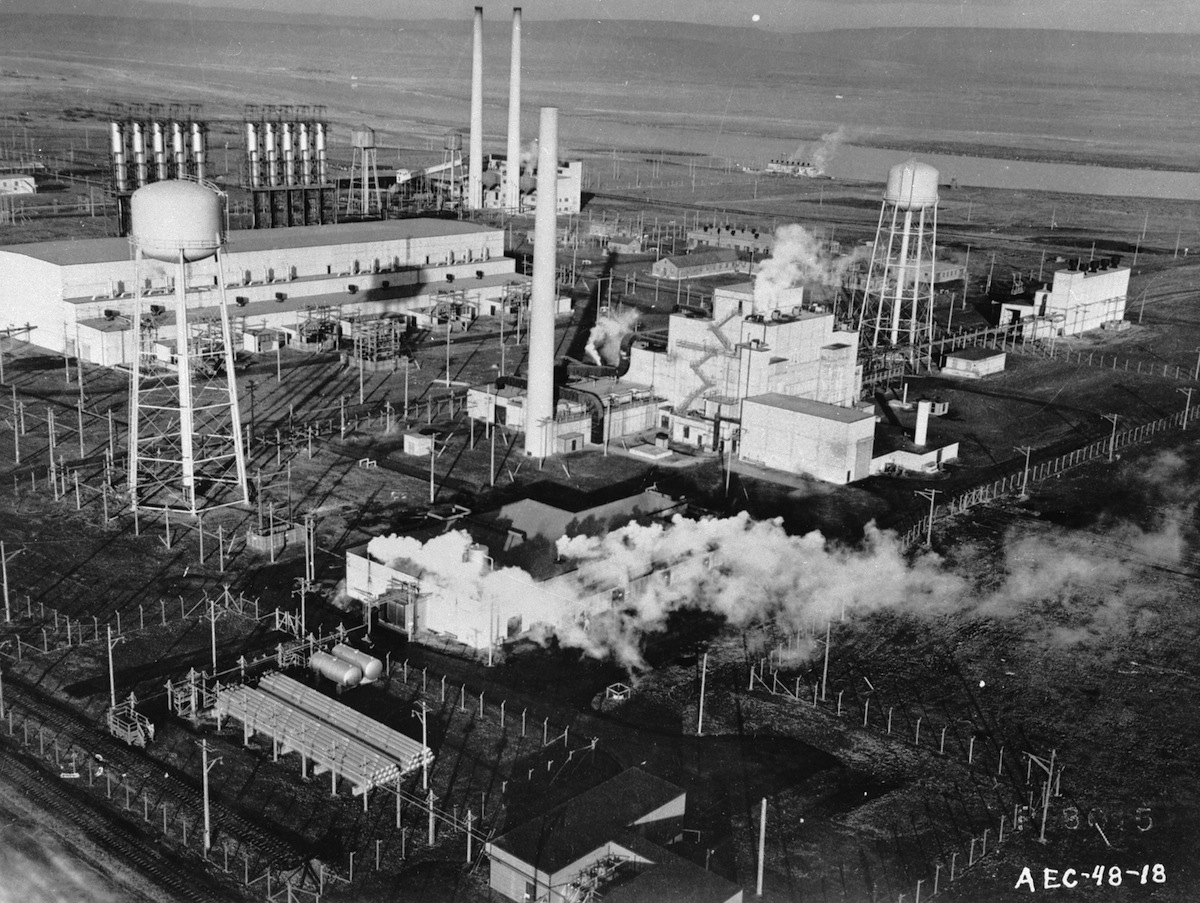

In 1951, atomic optimism was booming—even when it came to radioactive waste. In fact, entrepreneurs believed that the waste might pay off in the same way that coal tar and other industrial by-products had proved useful for the plastics and chemical industries. TIME reported that Stanford Research Institutes estimated they could sell crude radioactive waste from the Hanford plutonium plant in eastern Washington State at prices ranging from ten cents to a dollar a curie (a measure of radioactive decay). Every kilogram of plutonium the plant produced spilled out hundreds of thousands of gallons of radioactive waste. If the entrepreneurs were right, Hanford was a gold mine.

They were wrong. Instead, the former Hanford plutonium plant became the largest nuclear clean-up site in the western hemisphere. It costs taxpayers a billion dollars a year.

On the other hand, maybe they were right—just not the way they intended. Corporate contractors hired to clean up Hanford have made hundreds of millions of dollars in fees and surcharges, and, since little has been accomplished, the tab promises to mount for decades. Since 1991, the US Department of Energy has missed every target for remediation of Hanford’s deadly nuclear waste. Highly radioactive fluids are seeping toward the Columbia River watershed, while in the past two years 54 clean-up workers have fallen ill from mysterious toxic vapors. Last fall, seeking to finally get some action, Washington State sued the DOE to speed up the timeline and make the project safer—but, on Dec. 5, 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice rejected the request. The express schedule was too expensive, they said, despite the fact that the DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration is planning to spend a trillion dollars in 30 years to create a new generation of more accurate, deadly weapons. In fact, the DOE spends more money now in real dollars on nuclear weapons than it did at the height of the Cold War.

Unfortunately, the Justice ruling—to scrimp on radioactive waste management while the DOE spends lavishly on bombs—makes for business as usual in the history of Hanford.

It’s never been a matter of knowing the danger. In 1944, Hanford designers understood that the radioactive by-products issuing from plutonium production were deadly. Executives from DuPont, which built the Hanford plant for the Manhattan Project, called plutonium and its by-products “super poisonous” and worried about how to keep workers and surrounding populations safe.

At the same time, DuPont engineers were rushing to make plutonium for the first Trinity test in Nevada in 1945, and they did not pause to invent new solutions to store radioactive waste. Plant managers simply disposed of the high-tech, radioactive waste the way that humans had for millennia. They buried it. Millions of gallons of radioactive effluent went into trenches, ponds, holes drilled in the ground and the Columbia River. The most dangerous waste was conducted into underground single-walled tanks meant to last ten years. Knowing the tanks would corrode, as the high-level waste ate through metal, Hanford designers planned to come up with a permanent solution in the future. They were confident in their abilities. Had they not accomplished the impossible—building from scratch in less than three years a nuclear bomb?

But, as the years passed, no new answer surfaced to safely store nuclear waste. The Atomic Energy Commission, which was in charge of bomb production, left radioactive garbage to its private corporate contractors. For two decades, the AEC had no office to oversee waste management, nor any regulation. AEC officials didn’t know how much radioactive waste there was or where it was located. They also didn’t pay much fiscal attention to the problem. The AEC allocated to General Electric, which took over from DuPont in 1946, $200,000 a year for waste management, small change in nuclear-weapons accounting. In the same decade, the AEC handed over $1.5 million annually to subsidize the local school district in Richland, Wash., where plant workers lived.

Meanwhile, the temporary underground tanks remained long past their expiration date. In the early 1960s, the first tank sprang a leak. Dozens followed suit leaching into the ground a million gallons of high-level waste. From 1968 to 1986, Hanford managers built 28 new, double-walled tanks, designed to last from 20 to 50 years. What was the major design innovation after two decades of experience? An extra tank wall.

The explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986 tore the plutonium curtain of secrecy surrounding Hanford. The newly renamed Department of Energy was forced to release thousands of documents describing how plant managers had issued into the western interior millions of curies of radioactive waste as part of the daily operating order. In the early 1990s, TIME recounted stories of people living downwind who had thyroid disease and cancer, caused, they believed, by the plant’s emissions. In 1991, the DOE resolved to clean up the Hanford site.

The agency hired the same military contractors that had managed the site while it was being polluted. Their main task involved building a state-of-the-art waste-treatment plant to turn high-level waste into glass blocks for millennia of safe storage in salt caverns. But by 1999, eight years and several billion dollars later, the DOE had to admit that its contractors had accomplished little. Multiple times, the DOE set new deadlines or hired new contractors, but the goalposts were always moved. In 2015, after decades of effort, the waste treatment plant is still in the planning stages. High-level waste remains in tanks, some of which continue to leak.

What makes dealing with nuclear waste at Hanford so intractable? The Savannah River Plant in Georgia also made plutonium and has successfully built a treatment plant. So too have the Russians and French. Despite the Department of Justice’s ruling, money is not the main problem. The current contractor, Bechtel Corp, has spent billions of dollars, yet has made little progress. Speaking this week, representatives of the Washington State Department of Ecology said that they would argue their case in federal court in February, hoping to get the DOE to commit to their timeline to get the waste treatment plant up and running. Decades after the story began, it continues.

So perhaps it’s a matter of history. Since the ’40s, Hanford contractors had enjoyed a free hand to produce plutonium and pollute with little AEC/DOE oversight. And for six decades reports of radioactive discharges were denied. It is hard to fix a problem one cannot see—and that’s been, by any measure, an expensive lesson.

Kate Brown lives in Washington, DC and is Professor of History at UMBC. She is the author of several award-winning books, including Plutopia: Nuclear Families in Atomic Cities and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (Oxford 2013). Brown’s most recent book Dispatches from Dystopia: History of Places Not Yet Forgotten will appear in April 2015 with the University of Chicago Press.

Read a 1986 report on the safety of the American nuclear industry, here in the TIME Vault: Bracing for the Fallout

Read next: Tourists’ Trash Caused the Oddly-Colored Geysers at Yellowstone, Study Finds

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com