The Auburn Avenue neighborhood where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was born in January 1929 was both a spatial and human embodiment of Atlanta’s paradoxical reputation for both strict racial segregation and black economic success. Noted journalist and renowned apostle of the “New South,” Henry W. Grady, may have strained the credulity of his New York audience in 1886 when he insisted that he bore no resentment toward his beloved Atlanta’s arch-nemesis, General William Tecumseh Sherman, but Grady’s claim that “from the ashes he left us … we have raised a brave and beautiful city” was more than the idle boast of a shameless booster. Atlanta’s speedily restored railroad connections and postbellum emergence as the Southeast’s principal trade and transportation hub all but assured its magnetic allure. By 1900 it was home to 90,000 people, more than a third of whom were black. A bloody race riot in 1906 left at least a dozen and quite likely more black Atlantans dead, yet — with the city’s “Forward Atlanta,” crusade for economic growth proceeding apace — the city’s black population nonetheless continued to swell. It stood at 90,000 by the time King was born into a well-established black middle class of merchants, lawyers, educators (the city boasted six private black colleges well before 1900) and ministers, concentrated in the city’s West Side on and around Auburn Avenue, which a prominent resident once called “the richest Negro street in the world.”

If Atlanta had established a reputation as a relative mecca of upward mobility for black Georgians looking to better themselves materially, it had proved no less a font of opportunity for those of a more spiritual bent, including the infant King’s father and maternal grandfather, both of whom had been born into sharecropping families in nearby rural counties. Martin (né Michael) Luther King Sr. had arrived in Atlanta as an aspiring, though scarcely literate, young minister in 1918. His determined efforts to improve himself and his circumstances did not suffer in the least from his fortuitous marriage to Alberta Williams, whose own father’s meager rural origins had not prevented him from building his small congregation into the powerful Ebenezer Baptist Church, where, upon his death in 1931, he would be succeeded in the pulpit by his son-in-law. Growing up, the younger Martin’s solidly middle-class background offered some insulation from brutalities of the Jim Crow system, but there were no guarantees. Scarcely a year after King was born, Dennis Hubert, a sophomore at Morehouse College and also the son of a prominent black minister, was brutally murdered for allegedly insulting two young white women. For all this atrocity said about the limitations of middle-class standing for the city’s blacks, the young man’s white killers were arrested, convicted and sentenced to prison, an outcome highly unlikely, to say the least, in any rural county anywhere in the state at that point.

Step Into History: Learn how to experience the 1963 March on Washington in virtual reality

It was not surprising that a historian of that era found Atlanta “quite evidently not proud of Georgia” or that, across the state, all but a very few whites heartily reciprocated the sentiment. Indeed, this was the primary reason that Georgia’s overwhelming rural legislative majority had taken formal action in 1917 to quarantine the capital city’s insidious racial and political moderation. This was accomplished through the brazenly anti-urban artifice of the “county-unit” electoral system, which effectively guaranteed that the preferences of voters in Atlanta, population 270,000 in 1930, could be neutralized completely by those of voters in the state’s three smallest counties, which had a combined population of scarcely 10,000.

This was a situation tailor-made for a rustic, race-baiting demagogue like Eugene Talmadge. Peppering his speeches with the N word, stonewalling efforts to improve the schools, and reveling in the impotent rebukes of “them lying Atlanta newspapers,” Talmadge claimed the governorship for the first of four times in 1932.

For all he might have done to impede progress across the state as a whole, however, Talmadge’s impact on Atlanta itself was notably less severe. Despite the economic reversals of the Great Depression, the infusions of cash from a variety of New Deal programs had already paid off for Atlantans by the end of the 1930s, with a greatly expanded and modernized infrastructure and dramatic improvement in schools, hospitals and other public institutions. The overpowering urge to show the world that Atlanta was back and better than ever was more than apparent in December 1939 when the film version of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind premiered at the Loew’s Grand Theater. In keeping with the city’s now well-known penchant for self-promotion, PR-savvy Mayor William B. Hartsfield spared no exertion to assure a glittery Hollywood presence for the event including, of course, Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh and the film’s other white actors. Fearing repercussions from local whites, however, he extended no such hospitality to Hattie McDaniel, Butterfly McQueen or other black cast members. In the end, the only black participants of note in the entire affair were the members of the choir at the Ebenezer Baptist Church, including the son of its pastor. Just shy of his 10th birthday, Martin King sang along as, in keeping with the film’s blatant racial stereotyping, the group, dressed as slaves, performed spirituals for an all-white audience at a Junior League charity gala.

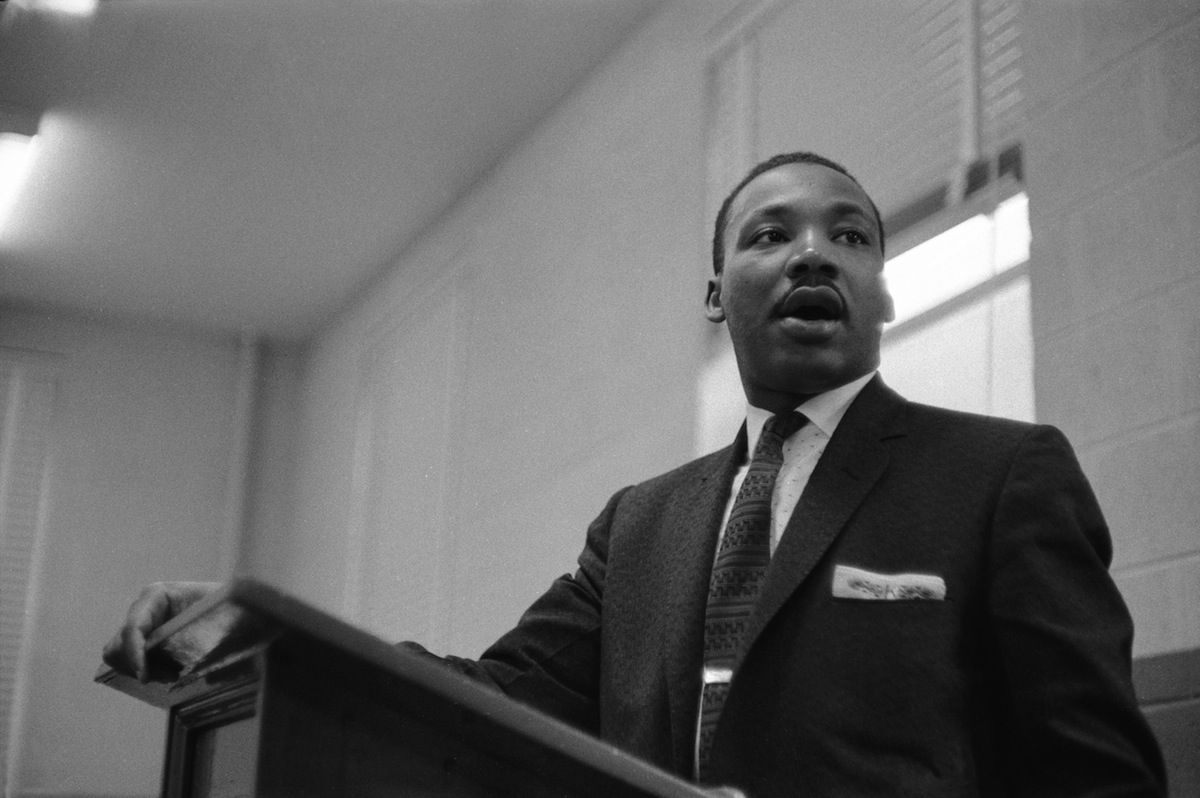

King and Hartsfield would cross paths frequently in the years to come. Under Hartsfield’s leadership, Atlanta would leave a racially fraught Birmingham, Ala., in its dust as it rode the crest of World War II economic expansion to undisputed pre-eminence as the South’s most dynamic city. Steadily changing with the times, the popular and uber-connected Hartsfield would draw on his gift for orchestration again and again as he presided over the desegregation of downtown businesses and the city’s tiny but notably uneventful first steps toward integrating its public schools. Meanwhile, returned to share Ebenezer’s bully pulpit with his father, the younger Rev. King began to cast doubt on the mayor’s vaunted claim that his city was “too busy to hate” by consistently pushing the envelope of social change further and faster than Hartsfield had envisioned. Though Atlanta had provided a unique environment in which King could become the man he was, the city still had a ways to go.

Atlanta had found its breezy, boosterist persona in the artful and charming Hartsfield. It would be slower, however, to acknowledge its conscience — the 1964 Nobel laureate who, the day after returning from Oslo amid global acclaim, forfeited the acclaim of the local business establishment by venturing scarcely two blocks from his church to join workers picketing for better wages at the city’s Scripto Pen Company. Ironically, but surely fittingly as well, some 30 years later, the plant’s remains would be bulldozed in order to provide parking for visitors to the city’s Martin Luther King Jr. Historic District.

James C. Cobb is Spalding Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Georgia and a former president of the Southern Historical Association.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com