In March 2014, two Albuquerque cops shot and killed a homeless man following a prolonged standoff in the foothills of New Mexico’s Sandia Mountains. It was an incident that could have easily become another instance of a police-related death without enough evidence to bring about formal charges against the cops involved. But a police body camera caught the entire confrontation on video, providing prosecutors the evidence needed to file formal charges—and perhaps launching a new era of increased prosecutions against cops thanks to the growth of wearable cameras nationwide.

Kari Brandenburg, the district attorney for New Mexico’s Bernalillo County, filed murder charges Monday against Keith Sandy and Dominique Perez, the two Albuquerque officers who were involved in the death of James Boyd, a homeless man with a history of mental illness who was camping in the mountain’s foothills. It was an open murder charge against both officers, which will let prosecutors decide whether to pursue manslaughter, first- or second-degree convictions.

MORE 2 Albuquerque Officers Charged With Murder in Shooting of Homeless Man

In video released last spring by the Albuquerque Police Department and recorded with a helmet cam used by one of the officers, Boyd is first shown arguing with police before a flashbang goes off. Officers then fire at Boyd as he appears to turn away from police. Boyd, who was carrying two knives, can be heard wheezing on the video as he’s being apprehended before he died. An autopsy later showed that Boyd had been shot twice.

“The video is instrumental in pointing out some of the issues in the investigation,” Brandenburg says, adding that the recording provides prosecutors with probable cause in a case that otherwise wouldn’t have it.

Advocates of body cameras often argue that recordings of officers on duty provide more transparency regarding police behavior and could even alter that behavior because officers know they’re being recorded. In Rialto, Calif., for instance, the police department began using body-worn cameras a few years ago, and its police chief often touts numbers showing that use-of-force complaints have decreased since officers began using them.

But experts say cameras might have an additional side effect: more prosecutions of cops involved in civilian deaths.

“Body cams should increase the number of criminal cases brought against police officers,” says Paul Butler, a Georgetown law professor and former federal prosecutor.

Oftentimes one of the barriers to prosecuting officers, Butler says, is that trials turn into “credibility contests” between police officers and civilians. But video evidence can go a long way to clearing up discrepancies about what happened while giving prosecutors additional evidence to move forward in a case.

MORE ‘Ferguson’ is 2014’s Name of the Year

“When there is doubt, people believe the police over civilians, especially when the civilians are suspects in some kind of criminal conduct,” Butler says. “Knowing this, prosecutors are often reluctant to bring charges against police officers, even when the prosecutors themselves believe the officers are guilty.

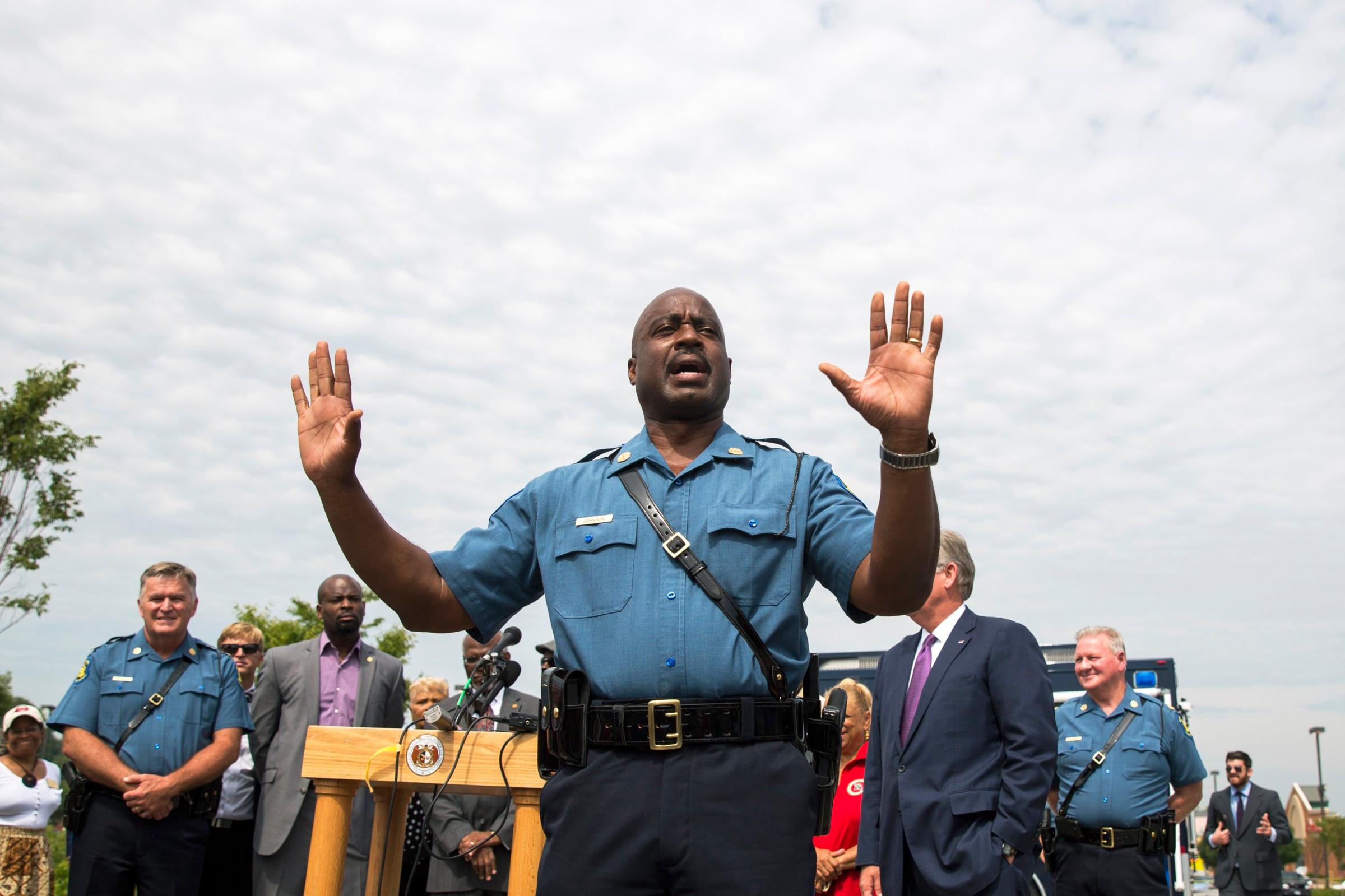

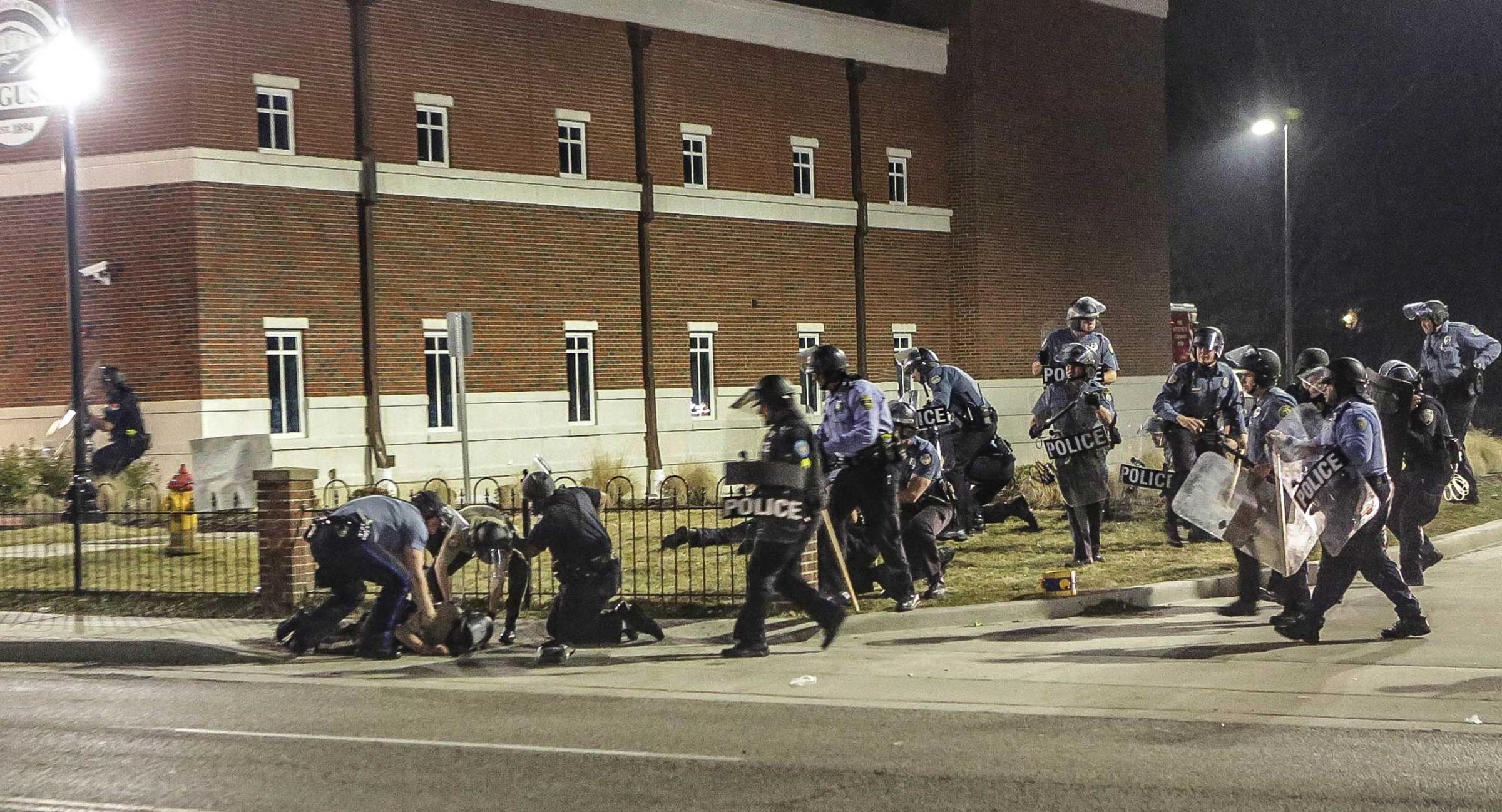

Many police departments around the U.S. have started using body worn cameras following the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager killed last year by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo. No video recording of that incident exists, and witnesses disagreed on the circumstances surrounding the confrontation between Brown and Officer Darren Wilson. Brown’s parents have been advocating for police departments to adopt cameras nationwide, believing that video recording of their son’s encounter with Wilson could’ve helped bring grand jury charges against the officer.

But cameras have their limitations. The fatal confrontation between Eric Garner and New York City officer Daniel Pantaleo, who placed the Staten Island man in a chokehold in July, was all caught on video by a bystander. Yet a grand jury still decided against bringing murder charges against the officer.

“The increased use of cameras both by agencies and by citizens will make it easier for prosecutors and defense lawyers to get a sense of what happened in a fraught encounter,” says Columbia University law professor Dan Richman. “The cases brought against officers may be stronger and the decisions not to charge may be easier. Still, the controversy surrounding the death of Eric Garner highlights how filmed encounters can be deeply contested.”

Justin Hansford, a Saint Louis University law professor, says he doesn’t believe more body cameras will necessarily equal more prosecutions because the definition of what constitutes use of force in most states are still weighted heavily in favor of police officers.

“The problems we’ve seen in places like Ferguson are not with the amount of evidence but with the laws themselves,” Hansford says. “When you think hard about use of force standards, officers have so much leeway that you have only a few outliers in terms of cases where prosecutions can go forward because of the laws really going above and beyond what is reasonable.”

Hansford argues that an increase in police prosecutions could come from a change in those standards, not in more body cameras.

“The harm of the body cam is that people think it solves everything,” he says.

See 23 Key Moments From Ferguson

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com