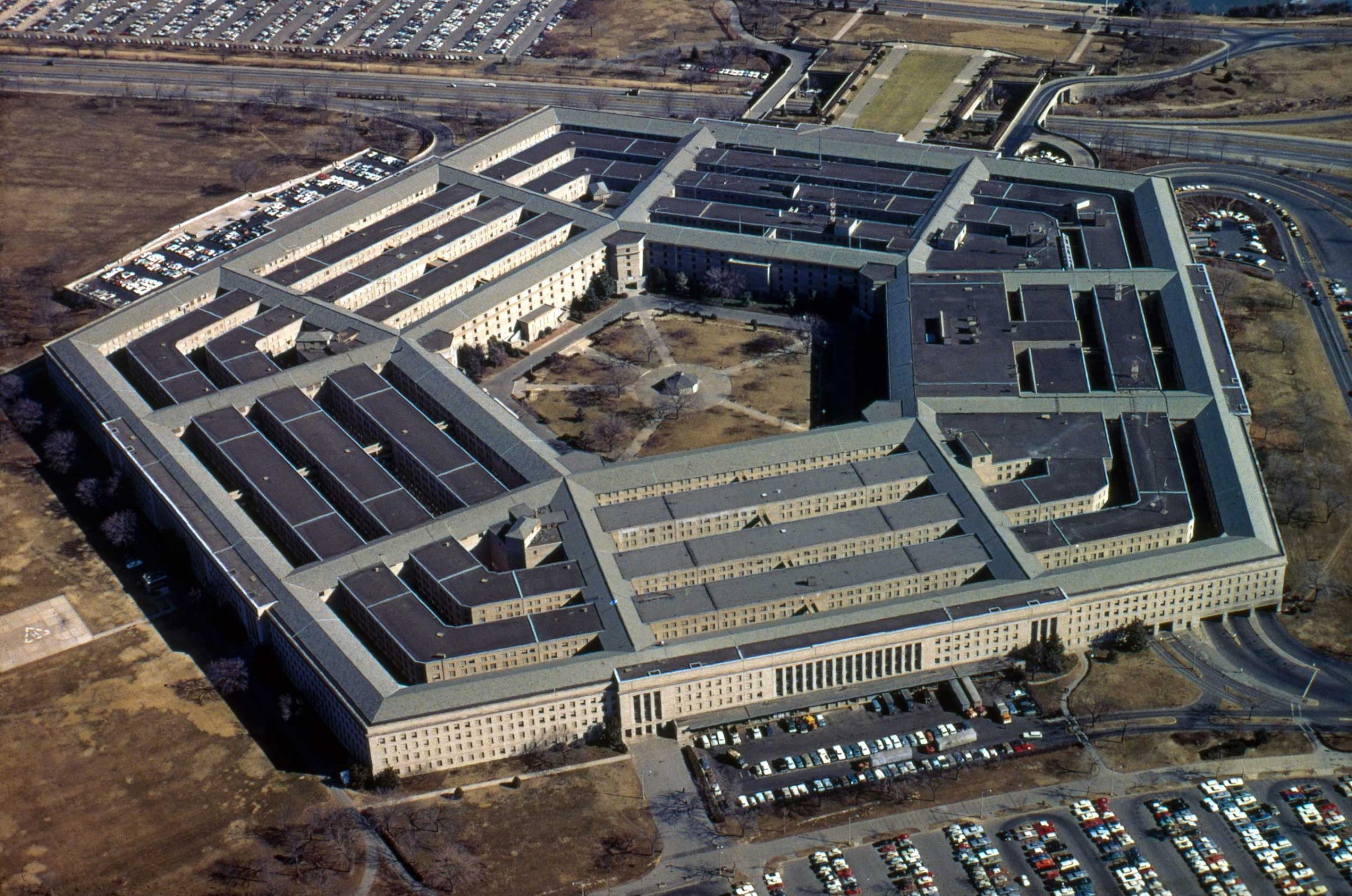

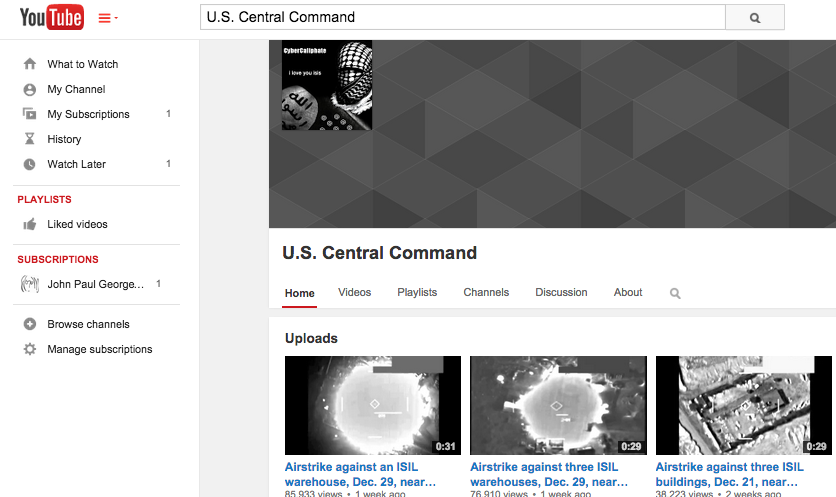

The Pentagon held its breath Monday when Islamic State sympathizers hacked into U.S. Central Command’s Twitter and YouTube accounts and began posting internal U.S. military documents on the Twitter feed.

Could this be another Snowden job? Was any of the material classified? After all, they were posting the names, addresses and phone numbers of senior U.S. military officers.

Within an hour, the Pentagon’s sigh was audible. While there was a lot of official-looking, internal documents posted before both social-media accounts were shut down, none of it appears to have been classified.

Many sported the officious-sounding but non-classified For Official Use Only label.

Monday’s bullet-dodging highlights the U.S. government’s preoccupation with secrecy, and its downside: when nearly everything is classified, it can be harder to protect real secrets.

Think of the government’s penchant for secrecy like an iceberg: what’s showing above the water line is that tiny share that’s classified Confidential, Secret and Top Secret.

But underwater—where, strangely, you can’t see—are more than 100 different designations that boil down to “Don’t let the public see this.”

For example, the non-profit Project on Government Oversight grumbled last year about the Pentagon inspector general’s routine requirement that any member of the public wishing to see some of its more interesting reports file a formal Freedom of Information Act request. “As anyone familiar with the FOIA process knows, turnaround on a request can take anywhere from a few weeks to a few years,” POGO’s Neil Gordon noted. “So, it’s reasonable to assume that the DoD IG is indeed trying to bury the report to spare the Pentagon and … its … contractors the embarrassing publicity.”

The varying labels—and each agency’s rules for releasing non-classified information—is confusing, as the Obama Administration itself conceded in 2010:

At present, executive departments and agencies (agencies) employ ad hoc, agency-specific policies, procedures, and markings to safeguard and control this information, such as information that involves privacy, security, proprietary business interests, and law enforcement investigations. This inefficient, confusing patchwork has resulted in inconsistent marking and safeguarding of documents, led to unclear or unnecessarily restrictive dissemination policies, and created impediments to authorized information sharing. The fact that these agency-specific policies are often hidden from public view has only aggravated these issues.

That’s why it wants to toss all those agency-specific labels into the trash and designate them all as Controlled Unclassified Information. Perhaps the reduced profusion of almost-classified labels will help reduce confusion like Monday’s (the Pentagon, of course, has its own process underway for all its non-classified technical data). And having the word Unclassified in the designation should make it clear to even cable-news anchors what’s up.

The Administration plans to issue a proposed regulation to funnel all the labels into that single Controlled Unclassified Information designation this spring. It’s slated to be fully operational in 2018.

Obviously, in addition to craving secrecy, the government abhors alacrity.

Read next: Twitter Hacking Gives Pentagon a Black Eye

Listen to the most important stories of the day.

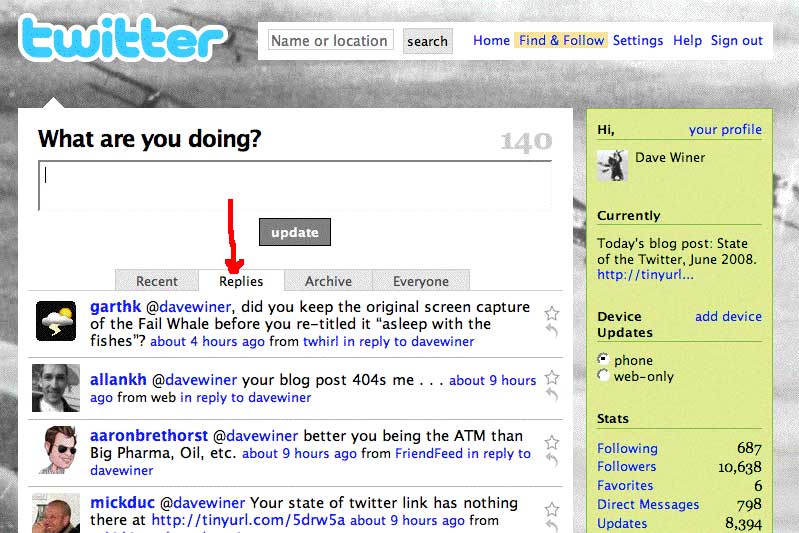

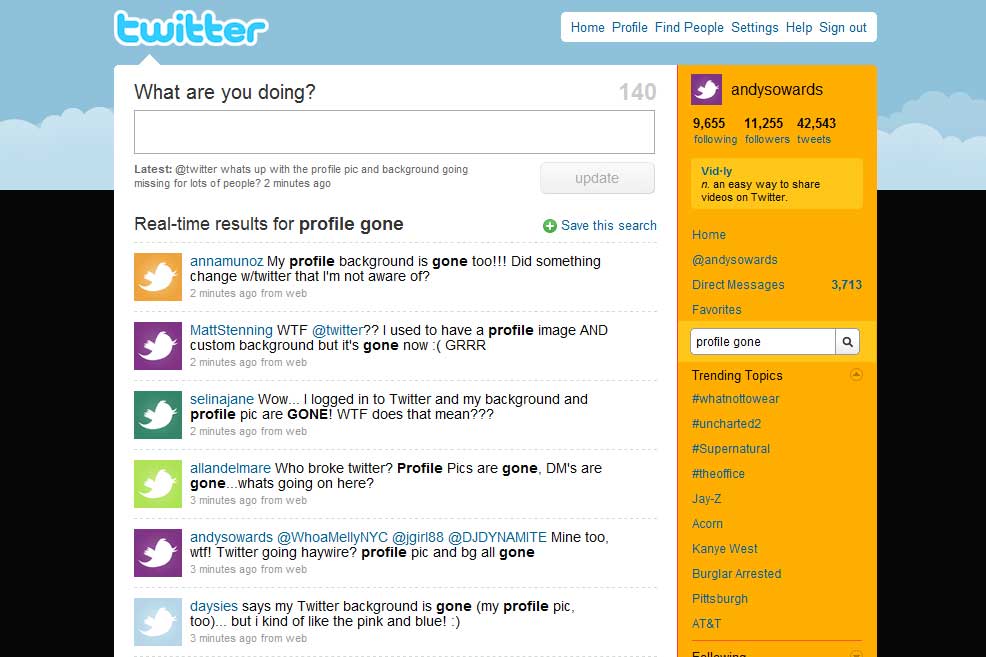

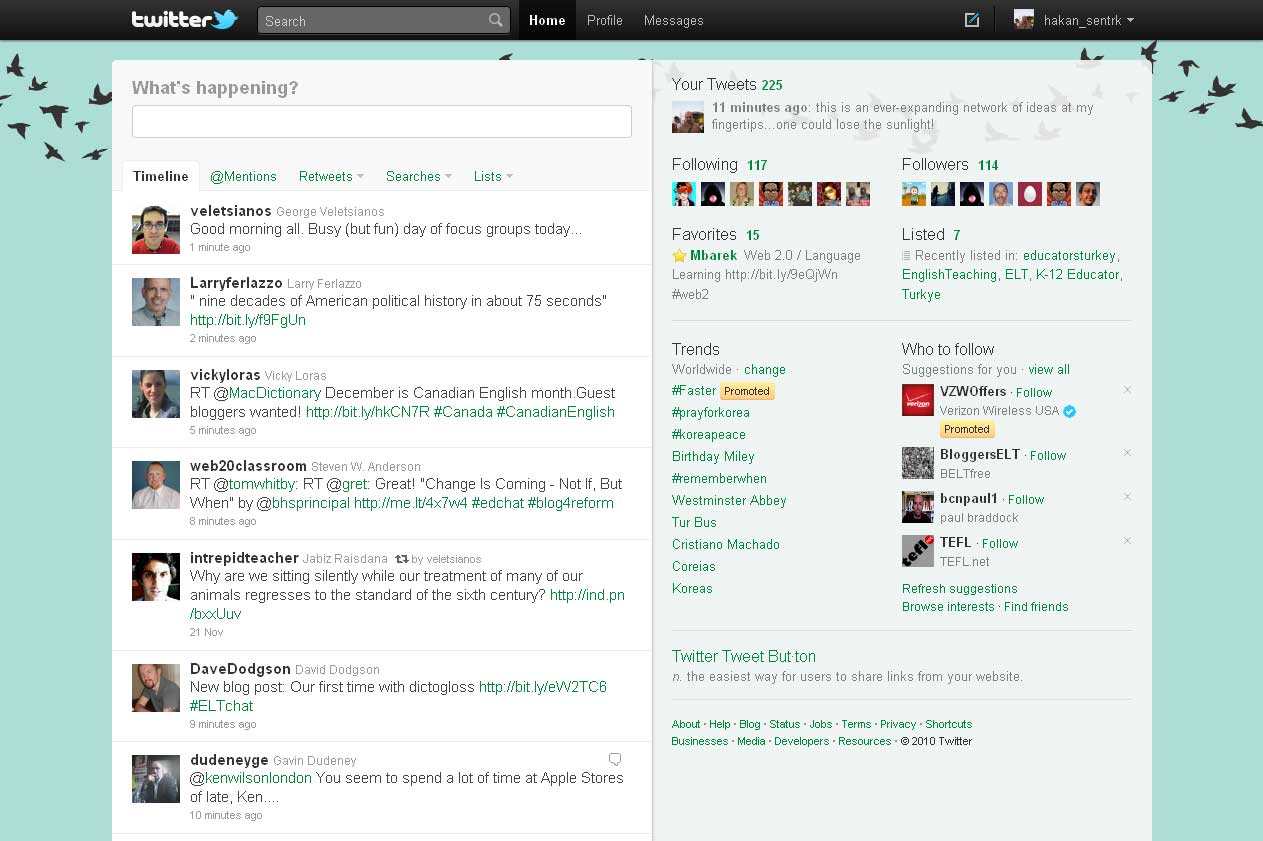

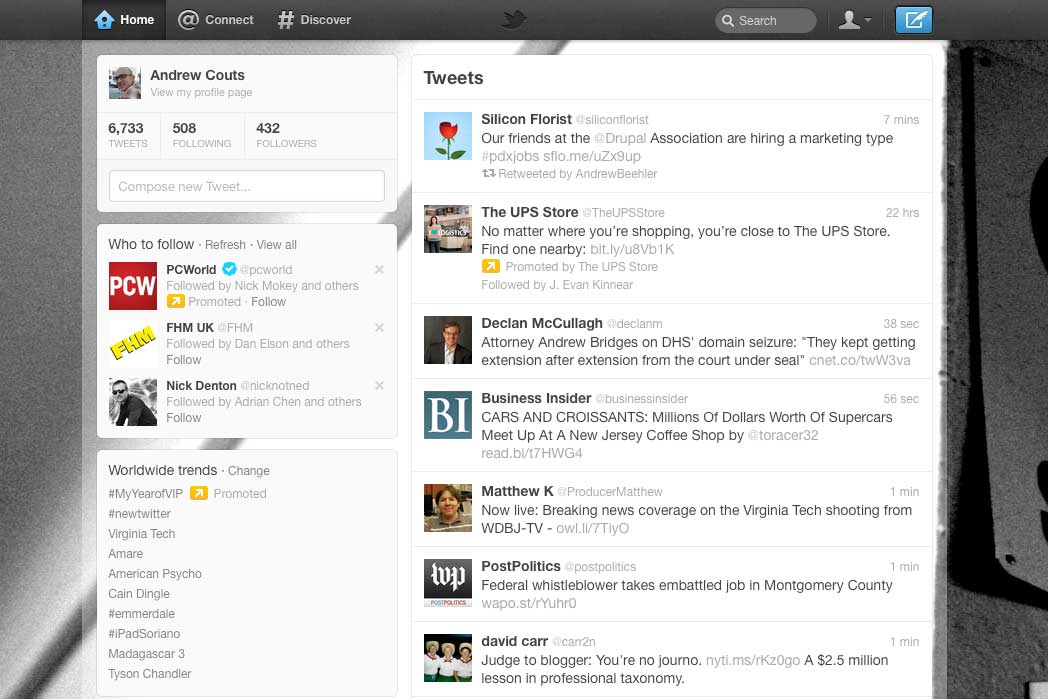

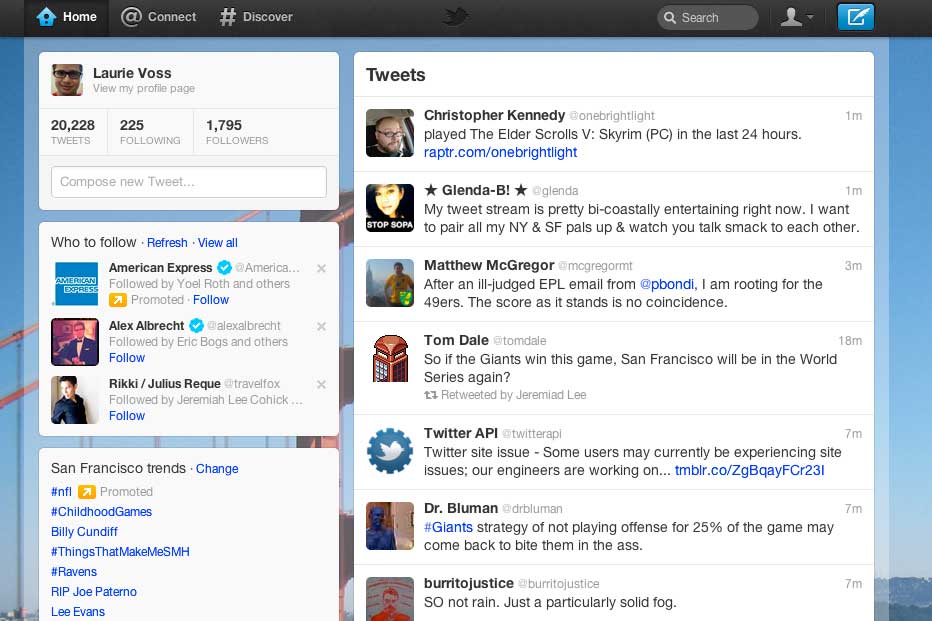

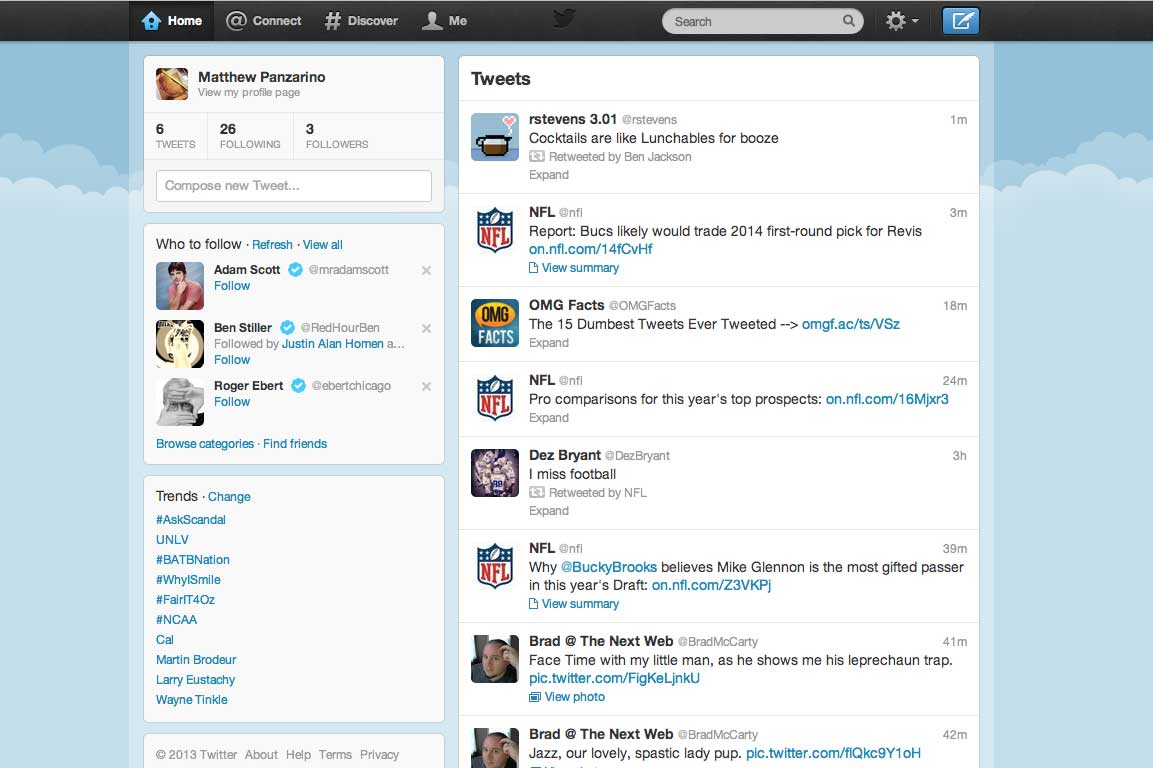

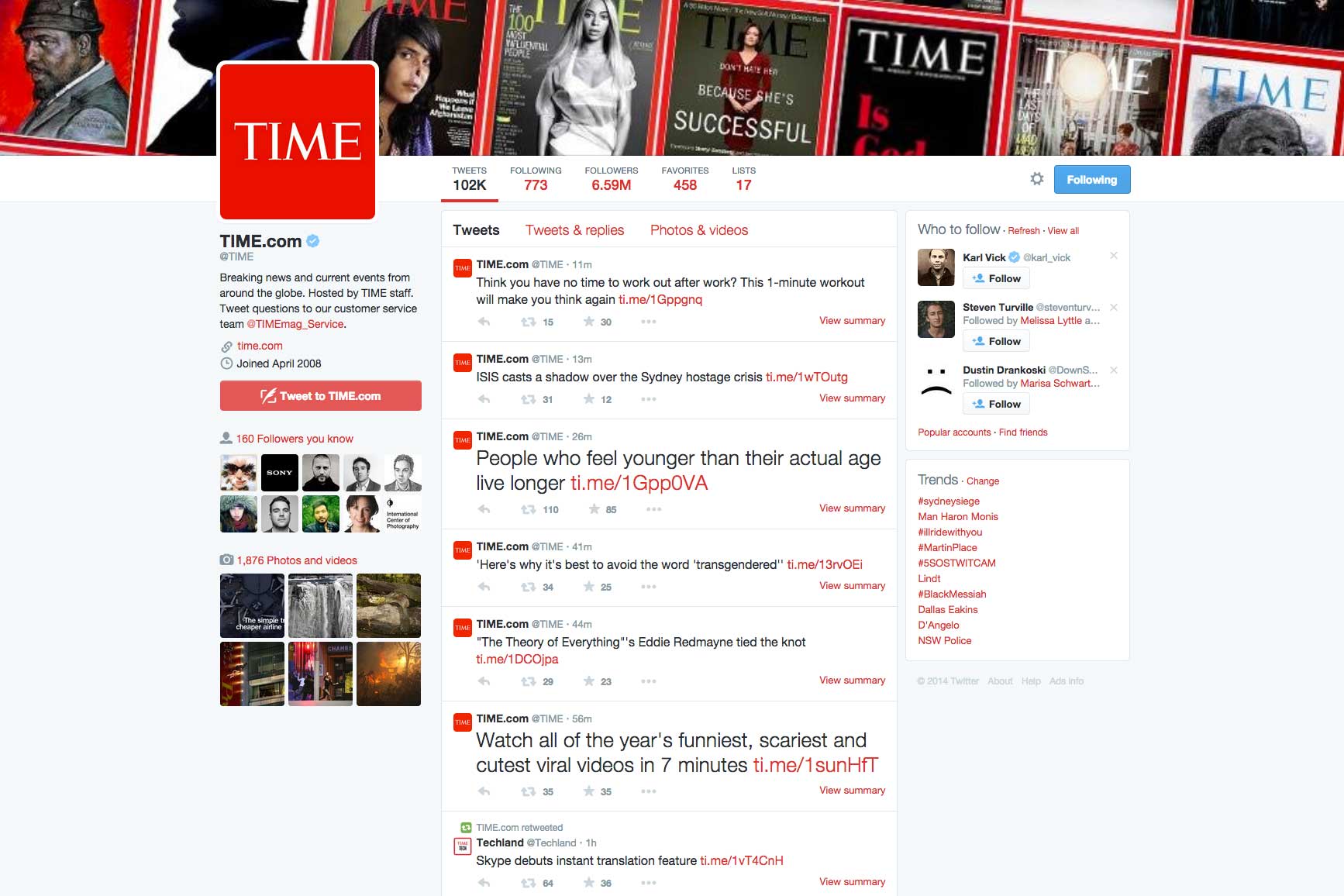

See What Your Twitter Profile Looked Like Over the Last 10 Years

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com