For decades, as Haiti has weathered political upheavals, coups d’état, economic crises and natural catastrophes—including the devastating earthquake that killed more than 160,000 people in 2010—photographers have nurtured an enduring, and at times tense, relationship with the small Caribbean country.

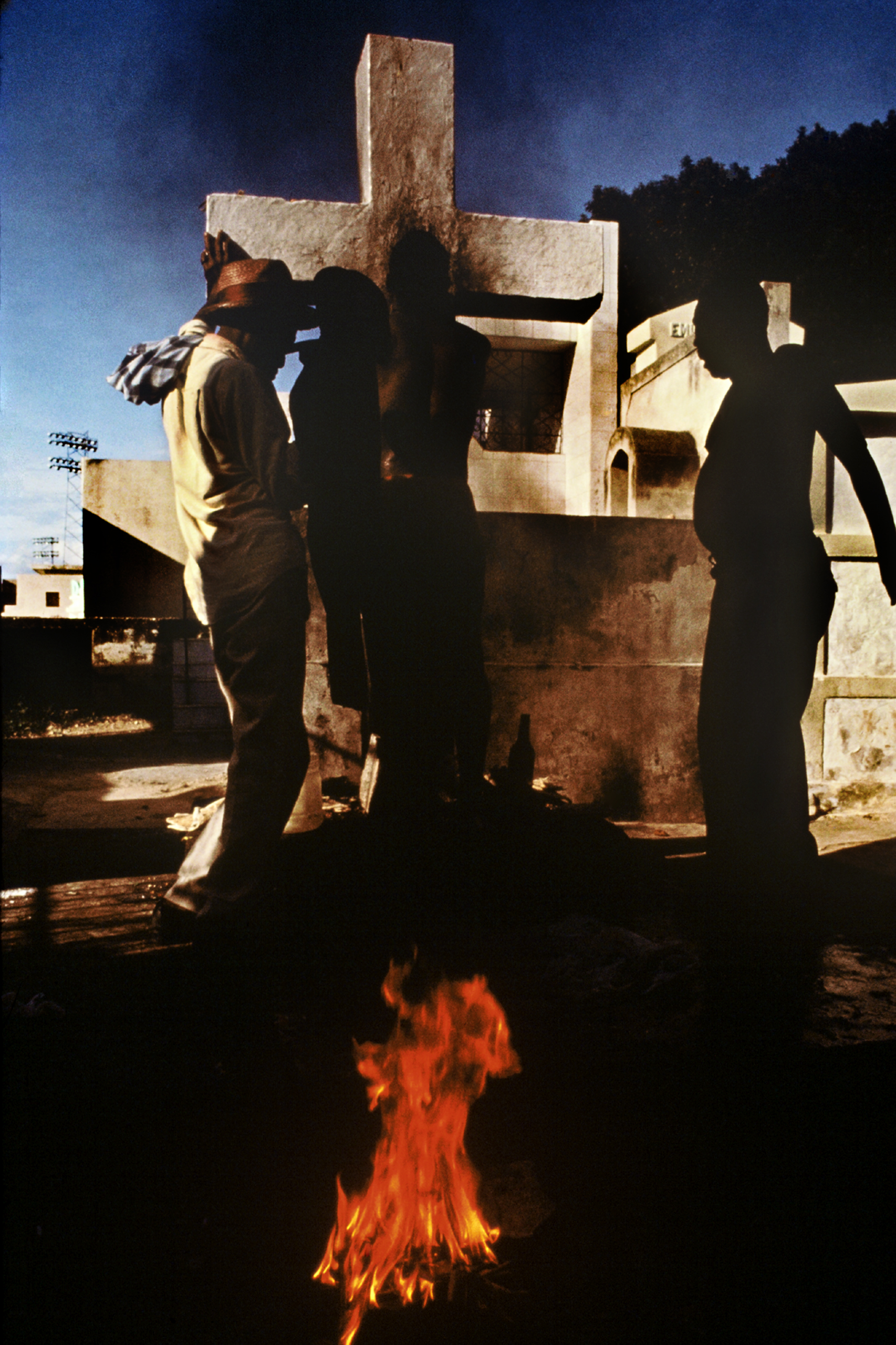

Haiti’s vibrant society, pulsating energy and stunning light, combined with its tragic and violent history, consistently attract photographers of all ages and nationalities. Many of them are inspired by Alex Webb’s seminal work Under a Grudging Sun, which continues, to this day, to influence their aesthetics.

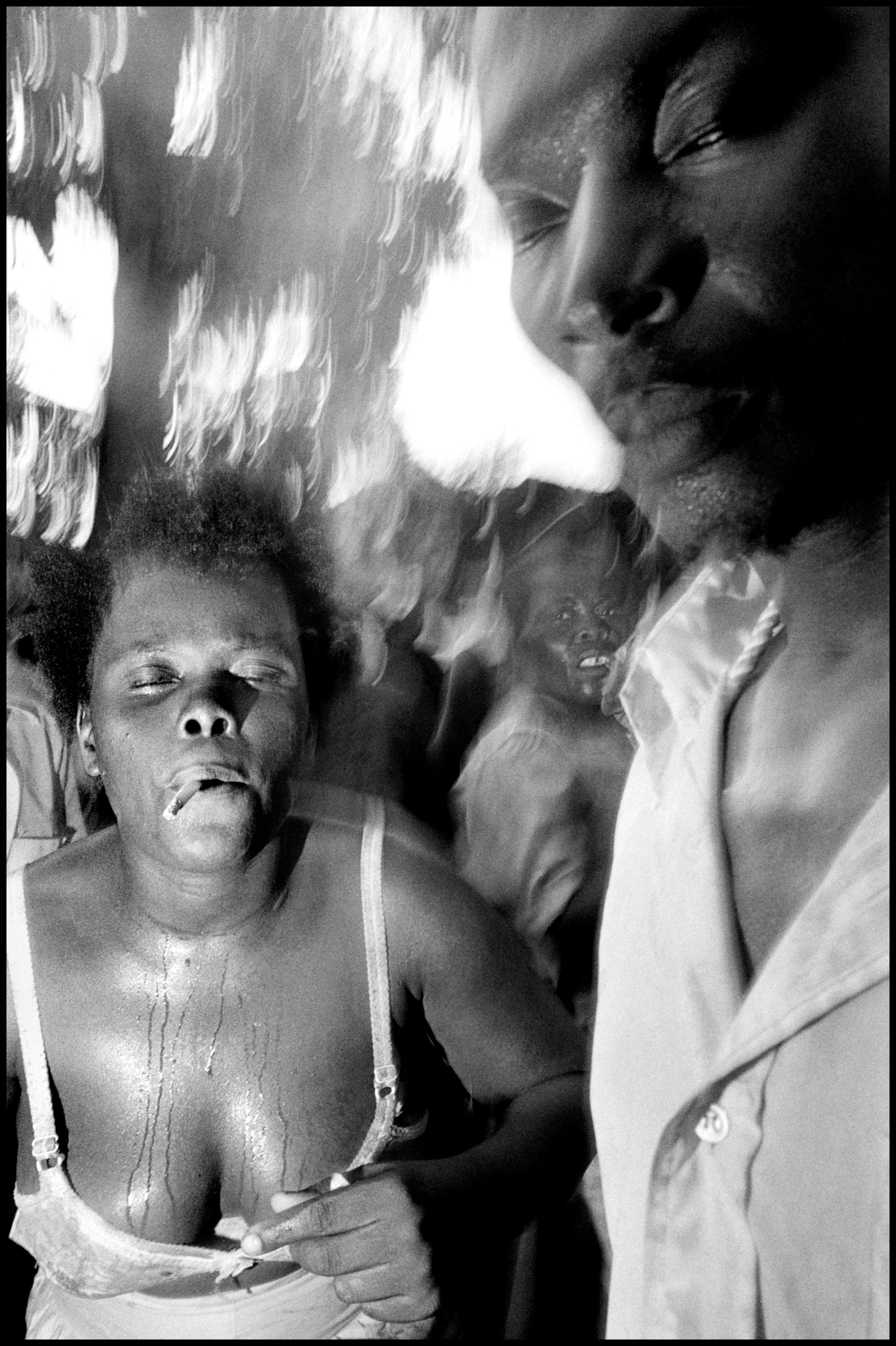

Webb’s first trip to Haiti, back in 1975, transformed him—both as a photographer and as a human being. “I photographed a kind of world I had never experienced before, a world of emotional vibrancy and intensity: raw, disjointed, sometimes beautiful, often tragic,” he tells TIME. “I encountered a world that kept drawing me back, again and again.”

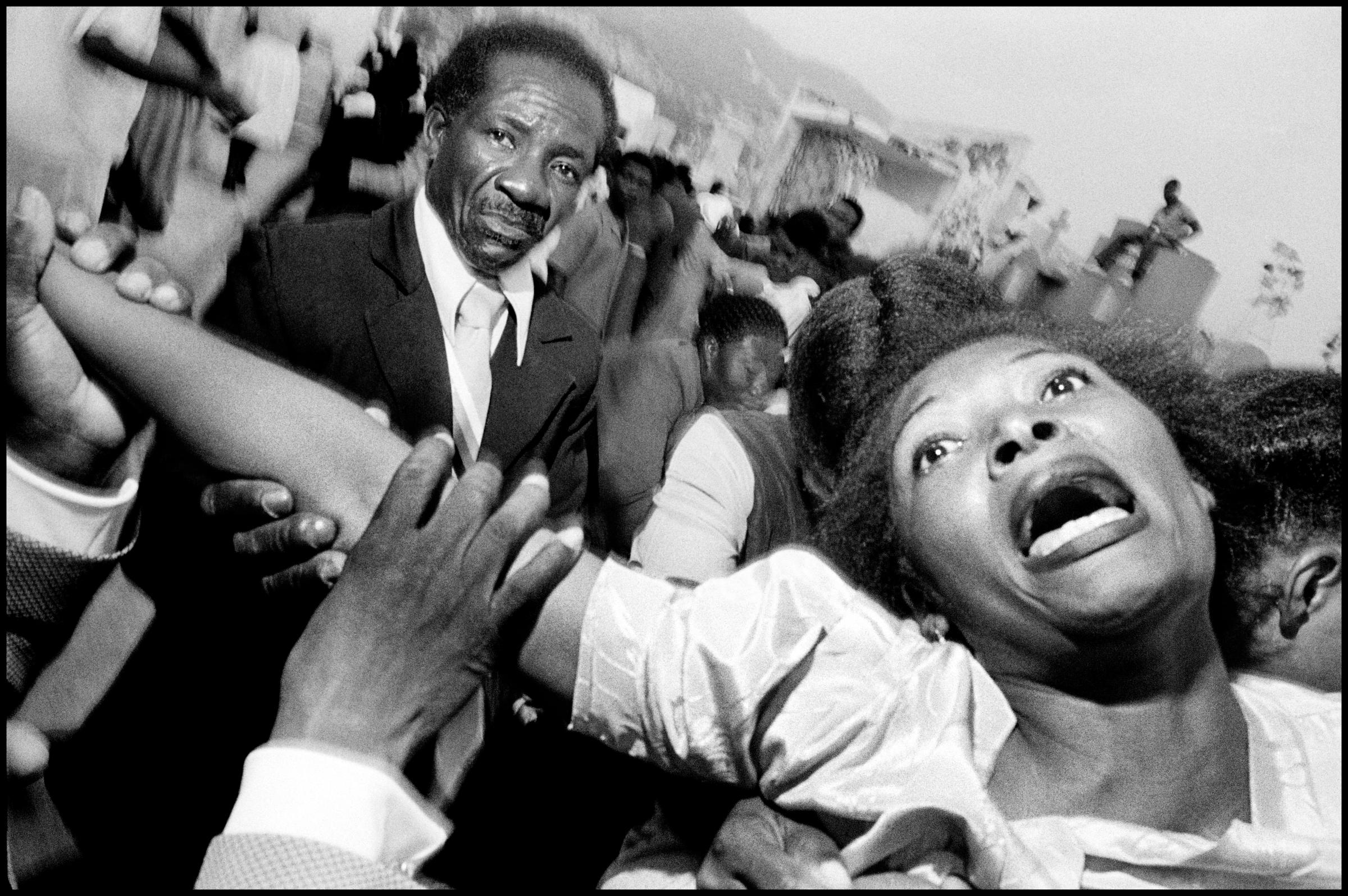

“I have this idea that Haiti chooses you,” echoes photographer Maggie Steber, who first visited the country 35 years ago. “If she doesn’t want you there, she will do everything in her power to make you run screaming for the next plane out of there. But if she likes you, if she recognizes in you a kindred spirit, she doesn’t let you go and she wrings your heart out every day. She uses you up.” Steber’s first experience with Haiti came when she moved to New York after living in Africa; she was missing living abroad and Sipa’s director Gökşin Sipahioğlu suggested that Haiti might satisfy that craving. She arrived just when President Jean-Claude Duvalier fell in a coup d’état.

“Then, everything exploded. It was thrilling. It was exciting. There was so much happening,” she recalls. “For the first time, people could really speak their mind. It was a country finally letting go after taking this deep breath. To me, that’s when the story really started to unfold. That’s when I was spellbound by it.”

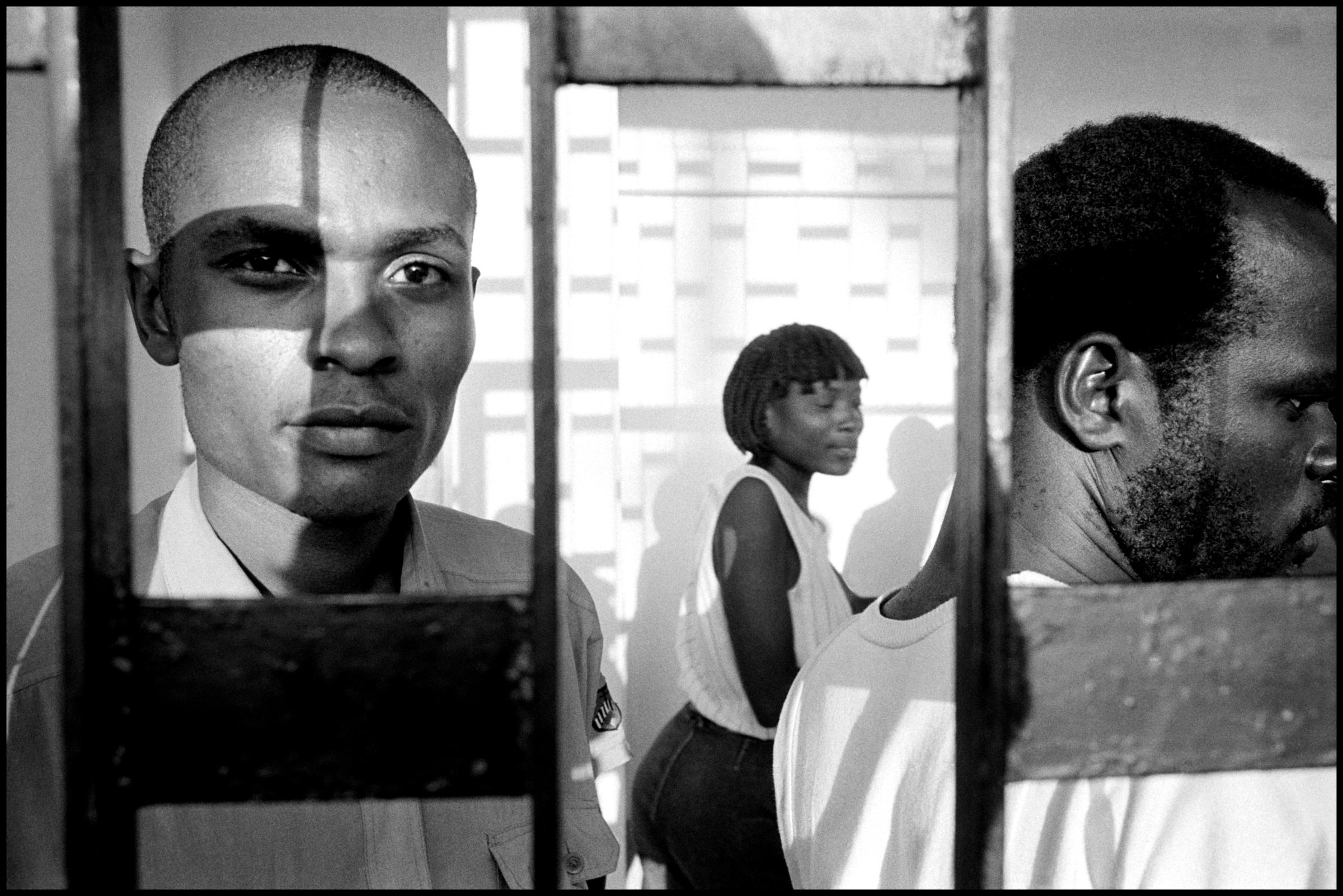

When Bruce Gilden first landed in Haiti in 1984, he rented a car with his first wife and, as he was driving to the hotel, he turned to her and said: “Where have I been my whole life?” Since then, Gilden has made 22 visits to the country. “Every time I’d go, I’d find something else to photograph,” he says. The stunning light hooked him first, but the reason he returned so often was all about the people. “They love me and I love them,” he says. “They are my people.”

Together, these photographers and many of their contemporaries have shot, published and exhibited thousands of images of Haiti—many of them with the stated goal of contributing to the dialogue about this “complicated country that has had such a difficult and tragic history,” says Webb. And yet, five years after a 7.0-magnitude earthquake destroyed large parts of Haiti and brought unprecedented attention to the country with billions of dollars of aid pledged and hundreds of NGOs setting up operations there, the situation remains grim, calling into question the photographers’ roles.

The deep connection many photographers feel when they first visit Haiti battles against the frustration many of them feel for a country that doesn’t seem to be able to escape its cruel fate.

“I do feel a frustration because every time Haitians try to take a step forward, something happens that sends them back two steps,” Steber tells TIME. “I think it’s frustrating for a lot of photographers.” For the Miami-based photographer, Haiti’s troubled situation can be traced back to the country’s slave revolt in the early 1800s. “Haiti had the only successful slave uprising at a time when the whole world’s economy was rotating around slaves, so the world turned its back on Haiti,” she says. “In a way, Haiti seems to have been punished by fate.”

In the last five years, the number of photographers visiting the small Caribbean country has surged, coinciding with the flock of NGOs pledging to help Haitians recover from the earthquake. While the organizations “are absolutely vital in moments of crisis or natural disaster,” says Institute photographer Paolo Woods, the situation in 2015 tends to show that in the long-term, NGOs’ impact on the country remains ambiguous. “I’m often asked what’s the difference between before and after the earthquake,” Gilden adds. “There’s no difference. Haiti is poor and nobody cares.”

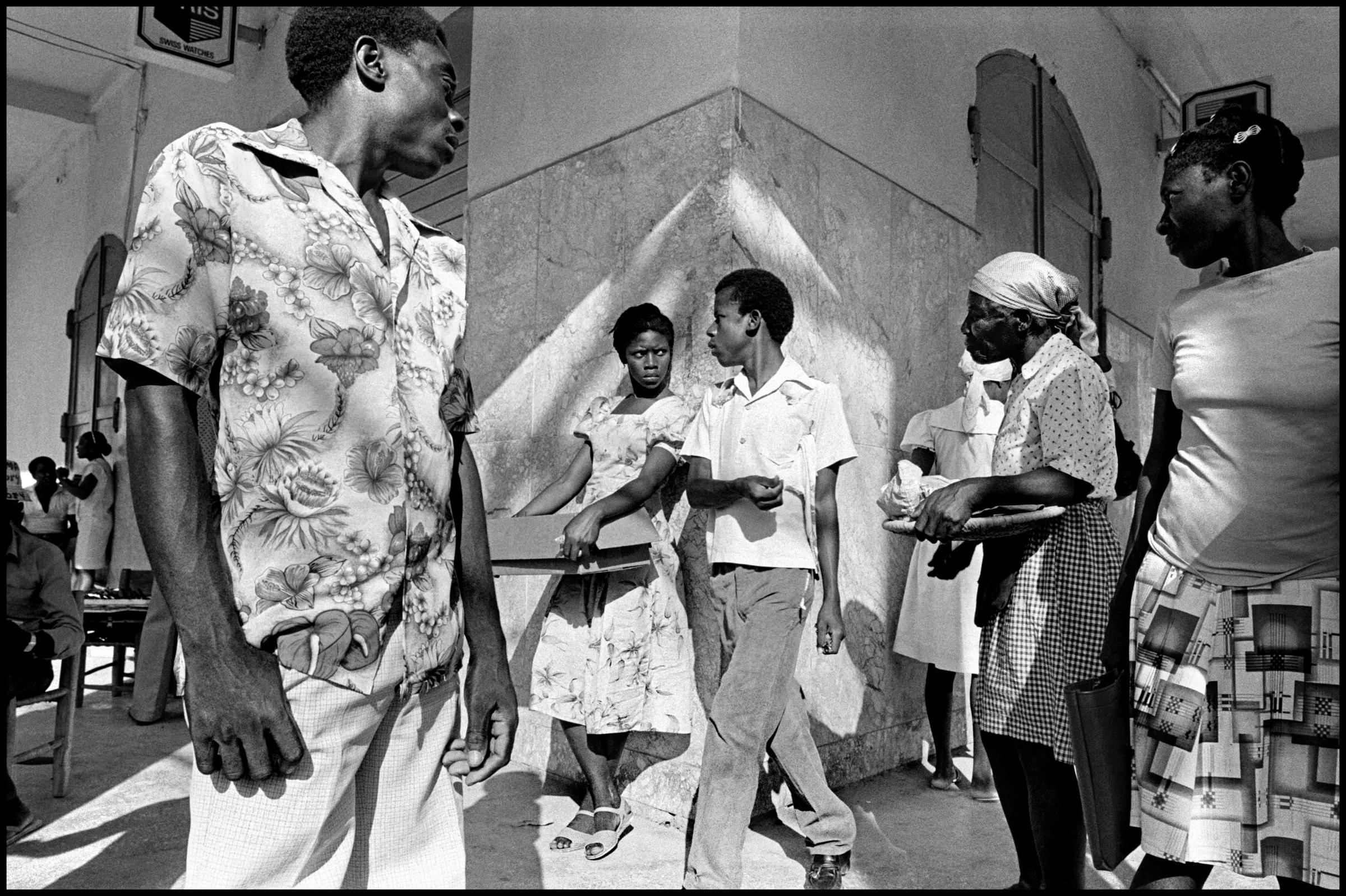

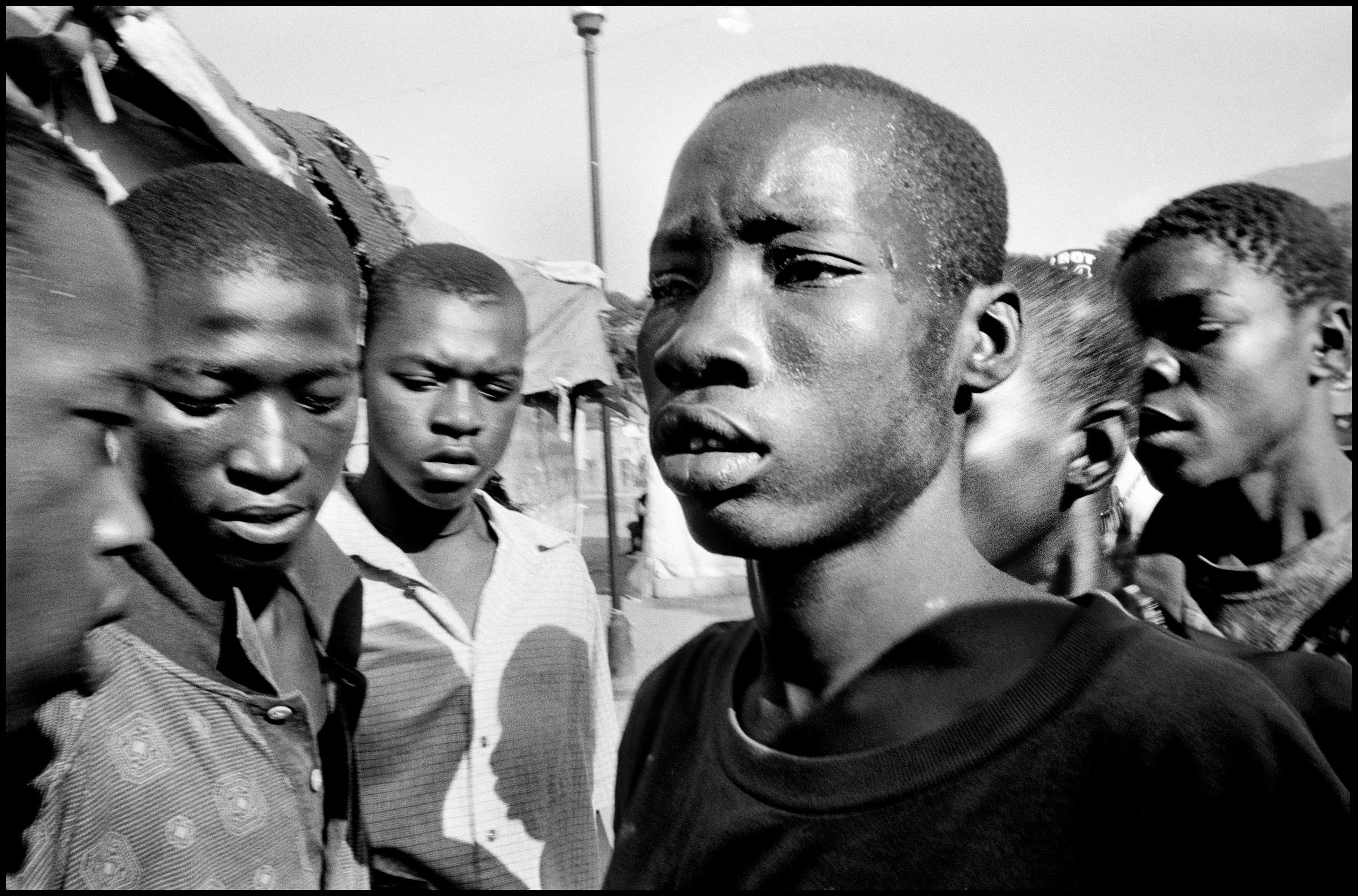

That’s a problem that hits home with photographers too. Though their goal is not the same as NGOs’, the nation’s poverty is ostensibly on display in their work, and they wrestle with how to show that world without harming the people in it. Photography that is not carefully considered can contribute, at times, to the reinforcement of stereotypes frequently applied to developing countries across the globe, from Africa to Latin America to Asia.

“As photographers, we tend to go to places with our eyes and brains already full of images, and very often, unfortunately, we try to confirm those images,” says Paolo Woods, who moved to Haiti five years ago to work on his book State. The photographer doesn’t deny that Haiti is crippled by its unstable political situation and deep-rooted poverty, but, he says, that’s only one side of the story. “When you look at images from Haiti, you get this impression of a country that’s very far away from what it actually is,” he says. “For me, it was just a matter of looking around [to find other stories to tell.]”

Woods only had to look around his hotel, where he stayed during his first month in Haiti, to find his story—one that centers on Haiti’s rich, upper-class population. “It was in December 2010, and we were getting close to the one-year anniversary of the earthquake, so a lot of journalists had come back to Haiti to do a story,” he says. “At that time, I was still living in a hotel in Port-au-Prince where a lot of media people gathered. What astonished me was that in this nice hotel, with working wifi and a swimming pool, you’d have all these photographers getting on motorbikes in the morning to go to Cité Soleil [one of the country’s poorest slums], take hundreds of images, and then come back to the hotel without ever looking at anything else.”

In the same hotel, in its lobby, restaurant and swimming pool, rich Haitians would come to wine and dine. “I thought this was interesting,” says Woods. “Who are these people? How did they make their money? How do they spend it? That became one of the multiple stories that built my book State.”

In his photographs, Gilden has tried to steer clear of the conflicts and the political mess, focusing, instead, on the everyday life of Haitians, whom, he says, he cares deeply about. Yet, his goal was never to change their lives. “I know [photographers] can’t change the world. If [we could], things would not be the same as they were 10 years ago, 20 years ago or 50 years ago.”

Some photographers—Steber and Woods included—have started looking for ways to give back to Haitians, often through photographic workshops. “I teach photography with the goal of encouraging education and to empower Haitians,” says Steber. “We leave the cameras behind and we come back to teach them again and again. It’s about training them to re-seize their country, to appreciate it and to see the possibilities for themselves.”

For Woods, it’s also a way to allow Haiti to be defined, photographically, by its own people. “I often get calls from NGOs, and I always try to refer them to Haitian photographers,” he says. “It makes a lot more sense. I think a country is healthy when its own citizens can tell its story.”

Certainly, Haiti, which is just a two-hour, $200 flight away from Florida, will continue to charm, attract and inspire photographers to produce “significant and deeply committed work, ranging from classical photojournalism to highly interpretive photography,” says Webb. And not just because “the country is poor, or has horrific political violence,” he adds. “There is something about the intense sense of life intertwined with the perpetual presence of death that courses through the society; something about the vibrancy of the people alongside the tragedy of their circumstances; something about a kind of beauty that co-exists with pain and sorrow. Trying to somehow come to terms with such paradoxes may well be a clue as to why the country has inspired—and continues to inspire—photographers as well as writers.”

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

Alice Gabriner, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s International Photo Editor.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com