Just past the grandeur of postcard Paris, with its boulevards and old palaces, lies what seems like a different world: The banlieues, or suburbs, vast stretches of small brick shops and mosques, and crumbling high-rise apartment blocks, which were thrown up hurriedly 50 years to house the huge influx of immigrants from the French-speaking countries of North and West Africa, and now are home to hundreds of thousands of French-born Muslims.

Five decades on – and not for the first time – violent events are forcing the French and their government to grapple with the seemingly intractable problem of how to bridge the divide between two very different strata of French society: The powerful and the peripheral. France has about five million Muslims, Europe’s biggest Islamic popoulation. And it is within these low-income cités, or housing projects, outside Paris, where youth unemployment rates hover around 25%, that the Charlie Hebdo attackers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, 34 and 32 respectively, spent years of their young adult lives before dying in a blaze of police gunfire on Friday. Amedy Coulibaly, 32, the gunman who fatally shot a policewoman on Wednesday and then seized control of a kosher supermarket on Friday before police killed him at sundown, also most recently lived in a Paris banlieue. In all, 17 people died at the hands of these three attackers, including eight journalists and three police officers.

As Parisians absorb the enormity of this week’s killings, residents in some of these banlieues say their areas need urgent changes – better education and more job opportunities – to reverse the growing drift of young Muslims like the Kouachi brothers toward radical groups bent on advancing their beliefs through violence. “These terrorists carrying out such attacks in the name of Islam tend to have lives marked by frustration and failure,” says Djemoui Bennaceur, 53, an Algerian-born resident in the suburb of La Courneuve, a low-income district situated just five miles from affluent central Paris.

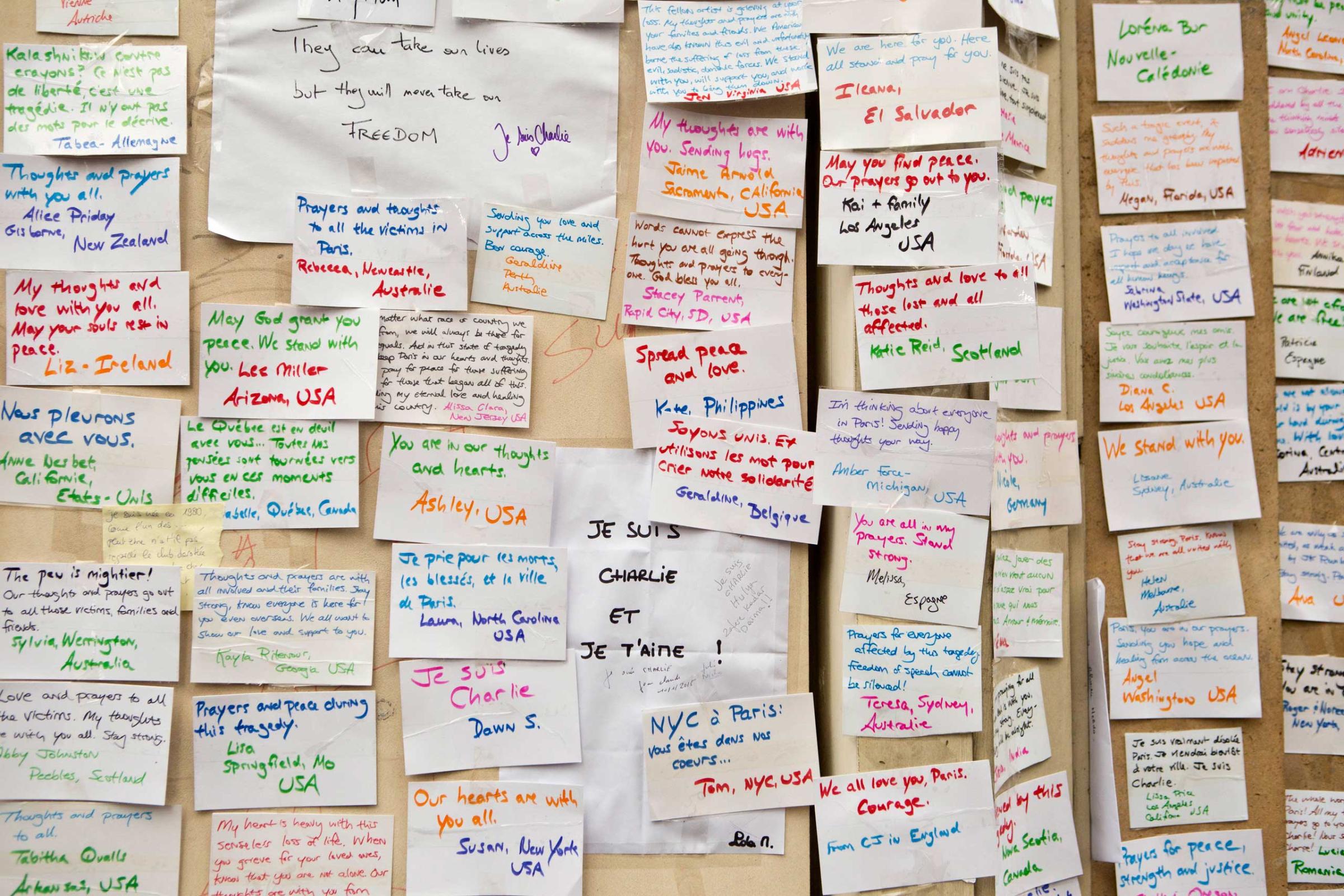

Large Crowds Rally Against Terrorism in Paris After Attacks

With French youth now wired and online, says Bennaceur, who emigrated to France in 1989 and is active in local politics, there are now plenty more opportunities for terrorist groups to recruit those stuck in dead-end suburban lives. “They are easily manipulated, particularly in a world where terrorists are experts in social media,” says Bennaceur, who runs a small shuttle service. That might partly explain the Kouachi brothers’ path to radical jihad, from a life of relative aimlessness. After the two became the prime suspects in last Wednesday’s massacre, during which they killed 12 people, Chérif’s former lawyer Vincent Ollivier described him to a French reporter as “part of a group of young people who were a little lost, confused, not really fanatics in the proper sense of the word.”

Both brothers worked occasional menial jobs and struggled to find steady work during their years living in low-income areas around Paris and elsewhere, according to French media reports this week. Chérif, who spent 18 months in jail in 2008 and 2009 for his jihadist activies, worked for a while delivering pizzas and in a supermarket in a Paris suburb. Orphaned at a young age, the brothers grew up partly in an orphanage in the western city of Rennes.

Older immigrants say they have witnessed a steady dwindling in young people’s prospects. “Things were not this way when I first came here 25 years ago,” Bennaceur says. “There were more opportunities to work and study. Since the financial crisis, that has changed and tensions have risen.”

When the Paris suburbs exploded in weeks of violent protests in November 2005, then-president Jacques Chirac vowed to pour billions into the banlieues with new housing, infrastructure and jobs. While there are some signs of that, investment has dried up since the recession hit in 2008, and as France has struggled with a ballooning public deficit. “After the riots the state did nothing,” says Farid Rebaa Jaafar, 52, vice president of the Mosque of Drancy, a suburb adjoining La Courneuve. “It became worse and worse.”

At least as urgent is anti-Muslim racism and what residents say is the persistent stigmatization of their neighborhoods. “The banlieues are still seen as shadow zones in France,” says student Sofiane Bouarif, 18, who was born and raised in La Courneuve, of Algerian immigrant parents.

Several French surveys have shown that many banlieue youth struggle to land job interviews — let alone jobs — solely because they have Muslim or African names, or because their addresses have zip codes signaling that they live in the poorer suburbs of Paris. Anti-racism organizations such as France’s SOS Racisme have long argued that job applications should be anonymous as a way of redressing the racial imbalances, and that the common French practice of including photographs on resumés reinforces racial stereotyping within companies looking to hire staff.

Many second and third-generation French from North or West African parents feel socially excluded from mainstream French society, despite being born within a half-hour’s train ride from the center of Paris. “They feel neither North African nor French,” says Jaafar, who arrived in Paris from Tunisia in 1979.

Jaafar says that for about five or six years, Muslim community leaders like himself have sounded the alarm about the need for change. “The state has not listened,” he says, adding that perhaps that change might finally come after the shock of this week’s violence.

Hundreds of Thousands March for Victims in France

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com