A group of Silicon Valley investors, scientists and chefs are close to debuting a plant-based egg. Omelet-maker extraordinaire Emily Kaiser Thelin investigates.

When I first met my husband, Josh, at a July 4th potluck barbecue in 2009, I had a strict rule against dating vegetarians—too much time spent defending my carnivorous ways. So I was crestfallen when the dashing stranger with whom I had been getting on so well suddenly plopped a veggie dog on the grill. I sighed and pulled out my bone-in rib eye. But as that steak cooked, with smoke swirling and fat spattering, Josh never flinched. When I carved into the medium-rare meat, he even asked how it tasted.

He explained that he’d never renounced meat—he’d just never eaten it. Ever. Since before he was born, his parents have eschewed meat and eggs. His father, Jay Thelin, cofounded the Psychedelic Shop on Haight Street in San Francisco in 1966. Jay was a rigorous idealist (he hoped LSD could expand the collective consciousness and end the war in Vietnam). Later, he discovered a spiritual path that convinced him that meat and eggs (and drugs and alcohol) hindered access to the divine. Out of a mix of habit, loyalty and pride, Josh has remained a vegetarian his entire life. He’s always been curious about omelets and steaks—just not enough to try them.

When we started dating, it felt good to eat more vegetarian meals. If I was missing meat, I ordered a roast chicken or braised pork shoulder when Josh and I ate out. Eggs became our only point of contention. On weekend mornings and at the end of a long day, I crave an omelet. Josh valiantly tries to win me over with his scrambled tofu, but, well, come on. Maybe I’ve succumbed to Francophile propaganda, but omelets, soufflés and other classics of egg cookery have always represented the ne plus ultra of independent adult living to me. And I make good omelets. When we got married, we joked that our lives would be perfect if only someone would build us a plant-based egg.

Last year, we learned that our absurdist fantasy was coming true. Big investors in Silicon Valley put $30 million into a start-up called Hampton Creek, where R&D scientists are building a vast database of legumes and grains (including often-overlooked ones like the Canadian yellow pea and sorghum) to determine which plant proteins can mimic—indeed, outperform—the properties of eggs.

The fact that the company’s founder, Josh Tetrick, is vegan has nothing to do with it. A former lawyer who’d worked in international development, Tetrick started Hampton Creek in 2011 to make sustainable food choices easy. “I fully support free-range eggs,” he says. “But my dad won’t buy them because they cost more. We’re looking for better and cheaper alternatives.” Industrially produced eggs seemed an obvious first target, he said, because of their many inefficiencies: food-safety scares, animal cruelty, high production costs.

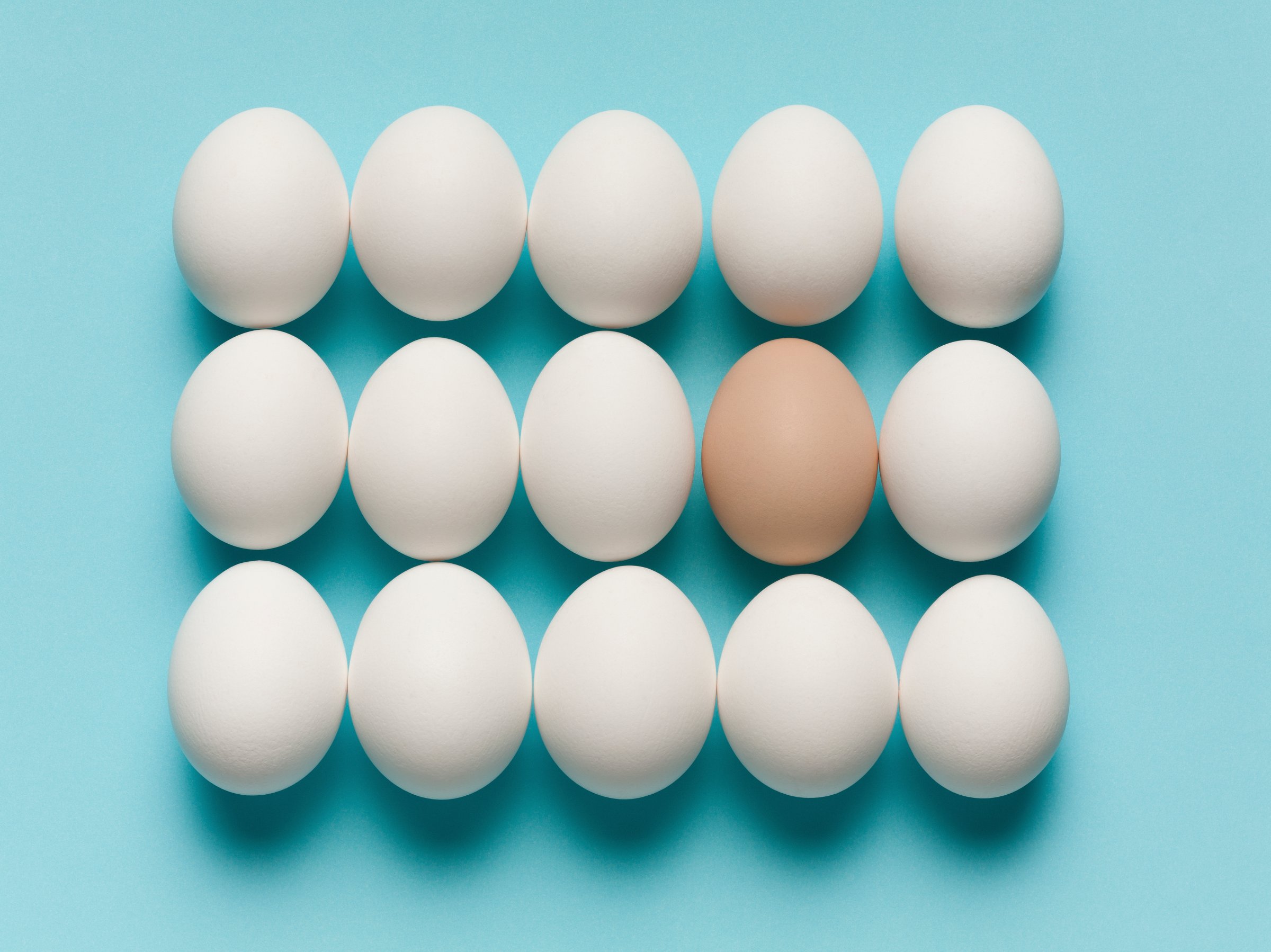

But how do you top an egg? As Auguste Escoffier wrote in Le Guide Culinaire “Of all the products put to use by the art of cookery, not one is so fruitful of variety, so universally liked, and so complete in itself as the egg.” Eggs poach, scramble and fry. They emulsify dressings, structure cakes, even clarify wine. There are vegan substitutes that can replicate certain facets, but can plant proteins mimic them all?

Just Scramble, Hampton Creek’s whole-egg alternative, is the company’s most ambitious project. As food scientist Harold McGee explains in On Food and Cooking, when raw, a real egg’s proteins float like tiny coiled ropes in watery suspension. When cooked (or whipped), the coils unwind and collide with one another to form a three-dimensional web. This web traps the air in a soufflé, thickens the milk in a custard, or suspends the egg’s own water in the curds of scrambled eggs. For a proper scramble, a plant-egg needs to create identically elastic and moist curds at the same pace.

Hampton Creek has hired three former chefs from Chicago’s avant-garde restaurant Moto who collaborate with its scientists on prototype after prototype. Their goal is to create something finer than an actual egg, with better flavor, more protein and less environmental impact. Recently, they found an iteration close to the real thing; it consists of a half-dozen ingredients, but contains no gums or hydrocolloids and nothing genetically modified. I wrangled an invitation to the facility so I could cook my husband his first omelet.

I was nervous: What if my husband just didn’t like eggs? I heated an omelet pan with a dab of oil, then poured in the liquid plant-egg. It looked just like a beaten whole egg, pale yellow and perfectly smooth (it’s only a coincidence—the plant strains are naturally yellow). I missed cracking egg shells one-handed, but didn’t miss cleaning a whisk and bowl.

As it cooked, the plant-egg gently and slowly transformed from liquid to solid, just like a real egg. I nudged aside the cooked curds with a spatula, and the uncooked parts pooled right in. A few curds on the bottom lightly caramelized but never turned rubbery or dry. I took the pan off the heat when the omelet’s center was just this side of runny. I added mushrooms I’d sautéed with garlic and white wine, shook the eggs to the edge of the pan, and then upended the omelet. Airy and elastic, it folded in on itself and slid onto the plate, a perfect package. “I can’t believe how quickly it cooks,” Josh said. “Scrambled tofu takes an age.”

I took a bite. Texturally, the omelet was spot-on. Flavor-wise, it tasted a bit grassy, like olive oil. If I was judging it as an egg substitute, I might have given it a 7 or 8 out of 10.

“We’d probably give this a 5 out of 10,” one of the chefs said. “Ours will have to be better than an egg.”

One thing I’ve learned about tofu scramble: It’s always better with cheese. I sprinkled grated cheddar on the omelet—the grassiness vanished. Now it tasted fantastic.

It may be months before Just Scramble is ready for market, but I’m happy to pass the time brushing up on omelet recipes: Escoffier’s Le Guide Culinaire has 31 pages of egg dishes, 11 for omelets and (real) scrambles alone.

This article originally appeared on Food & Wine.

More from Food & Wine:

Read next: Meet Nanosilver—The Tiny Pesticides In Your Food Products

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com