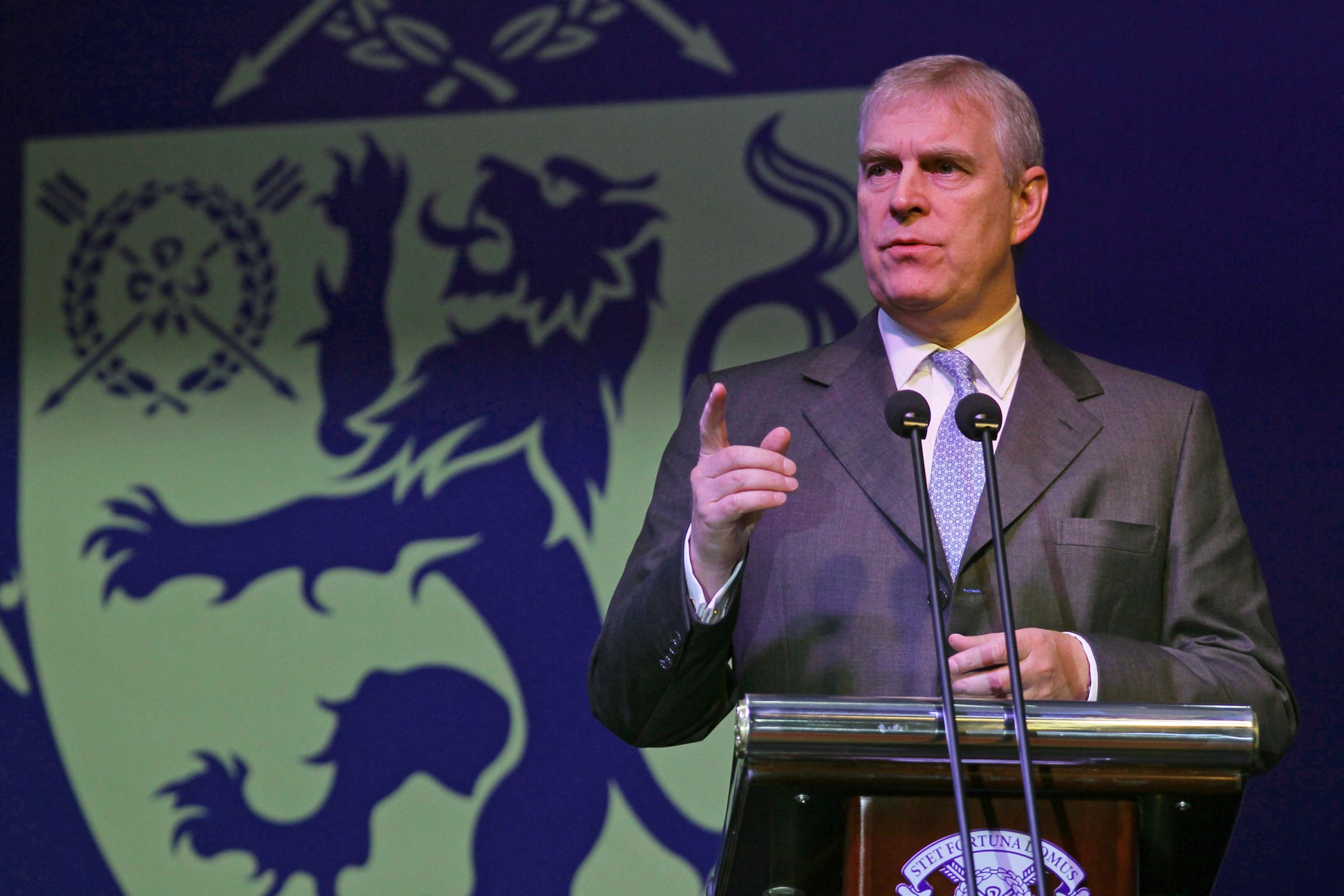

On its face, the story is more lurid than pulp fiction: A federal court filing accuses the Queen of England’s second son, Prince Andrew, of having sex in three countries with the self-described “sex slave” of an American financier, Jeffrey Epstein, who is himself a registered sex offender who settled a civil lawsuit by the woman out of court. A photograph exists of Prince Andrew smiling while he hugs the bare midriff of the teenage girl with his left arm.

The filing also accuses a famous Harvard law professor, Alan Dershowitz, an attorney for Epstein, of having abused the minor, and describes a larger criminal plot run by the financier to facilitate blackmail. The victim claims she was trafficked by Epstein “for sexual purposes to many other powerful men, including numerous prominent American politicians, powerful business executives, foreign presidents, a well-known Prime Minister and other world leaders.” These men are not named—yet.

Buckingham Palace denies the charges, as does Dershowitz, who threatens to sue the woman’s lawyers, including a former federal judge who argued last year before the U.S. Supreme Court, for disbarment. The woman’s lawyers sue Dershowitz first, accusing him of defamation for calling them “sleazy” in a CNN interview. An attorney for Epstein called the claims “old and discredited.”

But the oddest twist of all is not just that this is all really happening. It’s the reason why. The lawsuit that mentions these charges does not target any of the people who allegedly committed the crimes. Rather, it is aimed squarely at the U.S. Department of Justice, and its outcome could transform the way federal prosecutors handle high-profile criminal settlements in the future. “It’s a big case,” says Meg Garvin, the director of the National Crime Victim Law Institute. “If the Justice Department’s position stands, it eviscerates victims rights in a whole swath of cases.”

At issue is whether federal prosecutors have a legal obligation under the 2004 Crime Victims Rights Act to consult with victims of crimes during plea negotiations, even when settlements are reached before formal charges are filed. If a court eventually finds that they do, lawyers for four alleged victims of Jeffrey Epstein hope to throw out a plea deal he signed in 2007, allowing the prosecutors to seek new charges against him, and possibly others.

The roots of the case begin in 2005, when Florida police began investigating claims that Epstein was paying underage girls for sex at his West Palm Beach home. The investigation was later handed over to a U.S. Attorney, after investigators uncovered evidence that more than a dozen girls may have been victimized by Epstein.

After contentious negotiations, the Justice Department agreed to a deal with Epstein that required him to plead guilty to two state charges, including a single count of solicitation of minors for prostitution, to register as a sex offender and to serve a short jail sentence. Epstein also agreed to assist his victims in filing civil suits against him for the harm he had done. (Epstein later settled a civil suit filed by Virginia Roberts, the self-described “sex slave,” who has accused Prince Andrew and Dershowitz. Roberts’ initial filing in her 2009 civil suit included the claim that Epstein had required her to be sexually exploited by his “adult male peers, including royalty, politicians, academicians, businessman” and others.)

In exchange, the U.S. Attorney agreed to drop any further prosecution for the sex crimes, for either Epstein or the people who had allegedly helped him to recruit and pay the girls. The agreement also said that “the parties anticipate that this agreement will not be made part of any public record,” an unusual condition for such a criminal plea.

The outcome of the case shocked several of the victims, who felt blindsided both by the timing and the leniency. In the months that followed, two attorneys, a Florida trial lawyer named Bradley Edwards and a former federal judge named Paul Cassell, who is also a victims’ rights advocate and law professor, sued prosecutors for failing to properly notify the victims of the case, which they argued was required by the Crime Victims Rights Act. “This will send the message that federal prosecutors can’t keep victims in the dark about the plea arrangements they are making,” Cassell tells TIME about the rationale for the lawsuit.

The case has been now been ongoing for six years, with more than 280 filings. The Dec. 30 filing that set off the latest round of media coverage was a request to allow two other alleged victims of Epstein, including Roberts, to join the case. The district judge in the case is now considering a request from the lawyers to release documents that would shed light on the negotiations between the Justice Department and Epstein that lead to the settlement.

In legal filings, Edwards and Cassell have questioned, without specific evidence, whether there was external political pressure on the U.S. Attorney to keep the case from trial, either from Prince Andrew or former President Clinton, who traveled with Epstein on his private plane at the time but has not been accused of wrongdoing. “The elephant in the room is this: How does a guy who sexually abused 40 girls end up doing basically one year in a halfway house,” says Cassell, using one estimate of the number of victims in the case. “This stinks to high heaven.”

If the victims are successful, they hope to void the original settlement with Epstein, giving the Justice Department another shot at punishing Esptein. They also hope to set a precedent for future cases, forcing the Justice Department to consult with victims of high-profile crimes, even when the cases are settled out of court before formal criminal charges.

Ironically, the case may have already made some headway in changing the Justice Department’s behavior. In 2011, after Cassell and Edwards started the lawsuit, Attorney General Eric Holder released new guidelines for how prosecutors should work with victims, even in cases where no formal charges are brought. “In circumstances where plea negotiations occur before a case has been brought,” the new guidelines read, “Department policy is that this should include reasonable consultation prior to the filing of a charging instrument with the court.”

The Justice Department continues to maintain, however, that this consultation is not required by law.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com