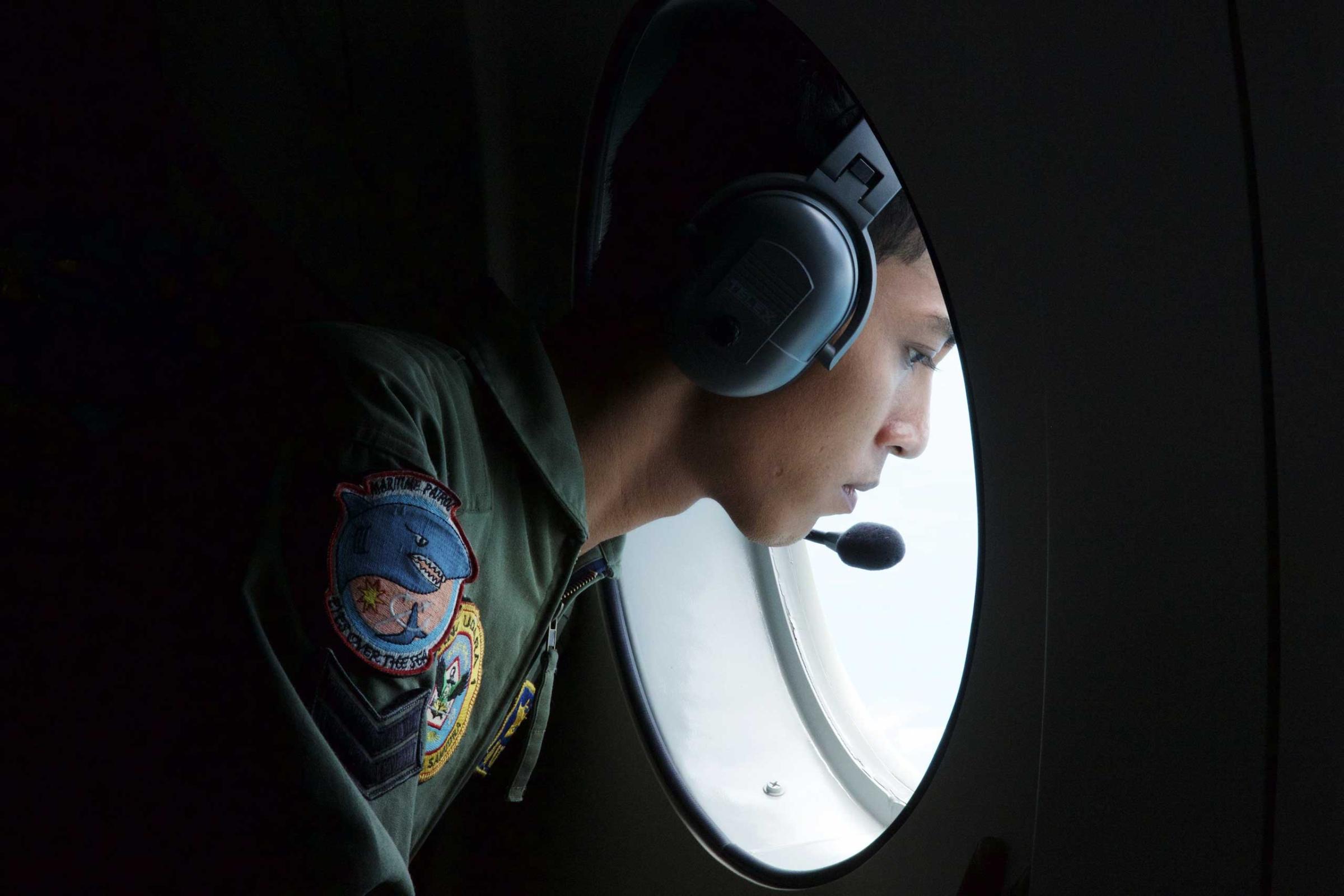

Divers plunged into the Java Sea soon after daybreak on Tuesday, desperate to use every possible second of a break in the weather to hunt for AirAsia Flight QZ 8501.

On the face of it, recovery operations for the ill-fated aircraft should be straightforward. The Java Sea is shallow, flat-bottomed and a well-traveled maritime thoroughfare, ringed by land on all sides.

So far, however, teams have only managed to recover 37 bodies. The remains of the other 162 passengers and crew, who are presumed dead, are thought be trapped inside the fuselage of the Airbus A320-200, which vanished 42 minutes after departing Indonesia’s sprawling port city of Surabaya for Singapore early Dec. 28.

But, 10 days into the search, nobody knows for certain where the fuselage is, nor have the flight-data recorders been found. (Although if the tail section has actually been spotted, as some believe it has, then there is a good chance of finding the black boxes, as this is where they are kept.)

So why has the search for the AirAsia jet proven so formidable in waters just 130 ft. (40 m) deep?

The answer is the weather, specifically the ferocious Asian winter monsoon, which turns the Java Sea into a tempestuous, murky soup. In fact, had the crash happened during a summer month, like August, it’s very likely that the wreck could have been spotted by simply looking down through the water on a bright, calm day.

“The plane really couldn’t have gone down at a worse time of year,” Erik van Sebille, an oceanographer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, tells TIME.

The Java Sea is so shallow it isn’t really ocean at all, from a geological perspective, but merely part of the continental landmass. During the last Ice Age, the whole area was above sea level and forested. “It’s tantalizing to think that just 20,000 years ago monkeys were roaming around there, and now it’s sea,” says van Sebille.

This means that rather than a rocky bottom, there is a thick layer of organic material that billows up with strong currents. This is exacerbated by monsoon rains lashing the surrounding islands, sending water into rivers that eventually torrents into the sea, depositing a thick layer of sludge and sediment.

Little wonder divers were forced to abandon efforts on Sunday because of near-zero visibility. Nor is it surprising that four large objects spied on sonar, which could be parts of the twin-engine plane, still have not been identified. (One earlier suspected object turned out to simply be a coral reef.)

The shallow water also affects wave patterns. While the Java Sea does not experience the enormous rollers of the open ocean, the area is characterized by extremely quick and precipitous waves that thrash around frenziedly, and are thus tricky to judge and work among. Combined with poor visibility, these choppy conditions mean divers risk being buffeted into debris — including the twisted pieces of jagged metal fuselage they are hunting for.

“It’s a very dangerous situation,” says van Sebille.

Such currents also explain why the search area expanded Tuesday from a 18,000-sq.-mi. (45,000-sq-km) primary search zone to include another 100,000 sq. mi. (260,00 sq km) farther east, in the direction where debris may have drifted. But the sheer mass of flotsam and refuse is another complicating factor. As well as assorted waste from all the surrounding populous islands of Java, Borneo and Sumatra, the Java Sea is thick with shipping traffic, and many vessels dump debris into the water.

There are also an untold number of wrecks from both ships and also other aircraft from as far back as World War II. All this debris tends to get churned around ceaselessly as “there’s not really a current flushing things out,” says van Sebille.

Even though practically every navy in the world has experience and equipment to allow operating at the depths posed by the Java Sea, the search for QZ 8501 has started to take on the same frustration as that experienced during the initial hunt for Malaysia Airlines Flight MH 370, which is presumed to have gone down in the seemingly bottomless Indian Ocean, and from which not a scrap of debris has been found.

As with MH 370, there is the desperate race to find the black boxes before their batteries run out.

Although locator ships have been deployed, no trace of the devices have yet been found. “We are racing against time, as their battery [will be used] up within 30 days,” Nurcahyo, an investigator with the Indonesian National Transportation Agency, told Xinhua. “Now we have 21 more days left.”

After another disappoint and fruitless day on the Java Sea, make that 20 — or even fewer, if bad weather persists.

Witness the Tragic Aftermath of AirAsia Flight QZ8501

Read next: For the AirAsia Bereaved, the New Year Brings Nothing but Grief

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com