A dose of Elon Musk has always been like a shot of strong drink. You think you can handle him, think you’re impervious to him—think you can hear him go on about private missions to Mars at just $500,000 per seat or freaky sounding hyperloops that would pack people into aluminum tubes and fire them from place to place at 800 mph (1,290 k/h)—and stay skeptical and sober. Then he starts talking, the buzz hits and you’re quickly calculating how fast you could come up with 500 grand for your own Martian holiday.

Part of the reason people believe in Musk is that Musk believes so wholly in Musk—even if he’s not exactly humble about it. Here he was speaking to Wired magazine in 2008, when SpaceX got off to a stumbling start after three straight launch failures: “Optimism, pessimism, f**k that; we’re going to make it happen. As God is my bloody witness, I’m hell-bent on making it work.”

Here was Musk in 2012, after one of his Dragon spacecraft splashed down following its first successful mission to the ISS: “In terms of things that are actually launching, we are the American space program.”

And here was Musk that same year, on the people who doubt him: “I pity them. It doesn’t make any sense. They’ll be fighting on the wrong side of yesterday’s war.”

That’s why it’s been such a happy surprise to hear him describe the upcoming launch of his Falcon 9 Booster, scheduled for 6:20 AM ET Tuesday. It will be the fifth unmanned resupply run that his company, SpaceX, will make to the International Space Station (ISS), but the first that will attempt to recover the first stage booster intact. That sounds like a very small deal, but it’s a very big one—especially given the way Musk plans to go about it.

One of the reasons space travel is so bloody expensive is that it’s so bloody wasteful. Expendable boosters—as their names make plain—are one-use-only machines, discarded stage by stage as they climb, with only the payload reaching space. The Saturn V moon rocket, easily the most impressive booster ever built, was also the most breathtaking example of throwaway tech. It stood 363 ft. (110 ft.) tall at launch, but the only piece to make it home was the 9 ft. (2.7 m) pod that carried the astronauts. The rest? Junk—most of it now lying on the ocean floor.

The shuttle program tried to remedy that. The ship’s whale-like external tank was dumped in the drink but the twin solid rocket boosters separated and returned by parachute when their fuel was expended, to be recovered and re-used. The shuttle itself, of course, came home, too. But the whole idea was oversold, with promises that shuttles could be checked out, gassed up and relaunched in a matter of weeks, slashing the price-per-pound of payload dramatically. Those weeks, however, turned out to be months, and every launch cost on the order of $400 million—not exactly a low-cost trucking service.

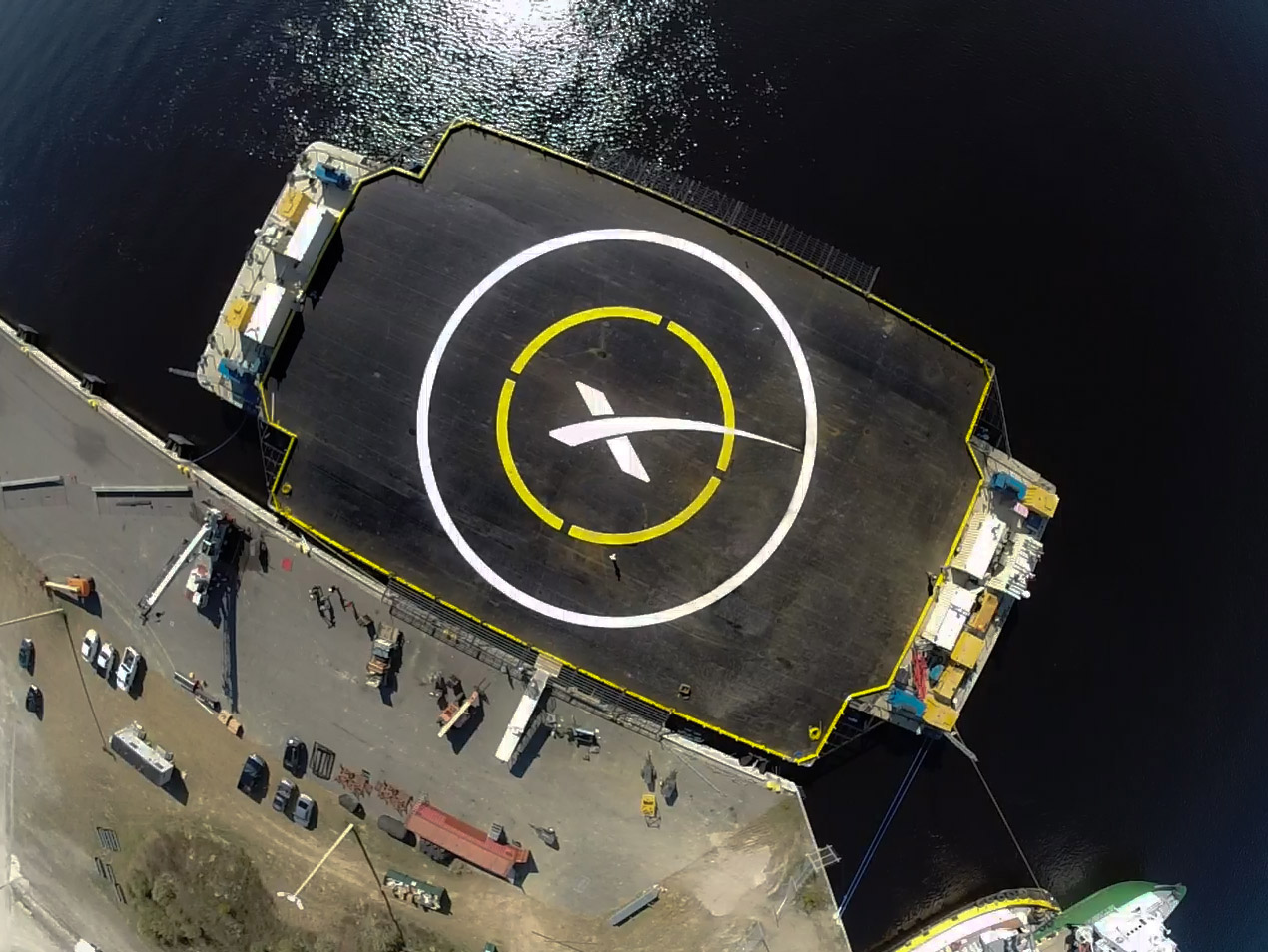

Musk aims to do things differently. After the upcoming Falcon 9 booster takes flight, its spent first stage won’t just tumble back into the sea. Rather, it will retain enough fuel to right itself and reignite for three separate burns, slowing its plunge from 2,900 mph (4,700 k/h) to 600 mph (965 k/h) and finally just 4.5 mph (7.2 k/h). Fins arrayed around the perimeter of the rocket will control its lift and attitude, and legs will allow to land upright on a 300 ft (91 m) by 170 ft. (52 m) floating platform that has already been built and is anchored in place 200 miles (322 km) off the east coast of Florida.

There are, admittedly, about one jillion things that could go wrong with this plan. Musk claims that the booster can land within 33 ft (9.1 m) of an intended target, but with the leg span of the rocket a full 70 ft (21 m) and and platform’s mere 170 ft. width, that leaves very little margin for error. The rocket stage itself is 140 ft. (42 m) tall—about the height of a 14 story building—but because of its relatively light weight and cylindrical design, SpaceX’s own website compares trying to stabilize the stage as the equivalent of balancing “a rubber broomstick on your hand in the middle of a windstorm.”

That’s fine for the PR-minded folks who write the website and are in the business of lowering expectations so they can easily exceed them. But surely Musk—who is his own kind of windstorm—will be less reticent. Not so. He puts the likelihood of success on this first attempt at less than 50-50, and, in an interview with The New York Times, admitted that it could take a dozen flights before the new landing system will reach even 80% to 90% reliability, which sounds impressive but is still below what it will cost to keep costs as low as Musk believes he can drive them.

It’s hard to say what’s behind the candor and caution coming from a man known best for boasts and bravado. Part of it may be the humbling that Orbital Sciences—SpaceX’s main competitor—experienced when one of its rockets exploded en route to its own space station rendezvous in October. Another part, surely, was the far worse loss of Richard Branson’s SpaceShipOne shortly after, which cost the life of a pilot.

Musk is now the biggest name in the frontier field of private space travel and that—plus the realization that he’s no more immune to disaster than anyone else is—cannot help but have a sobering effect. Space seems easier when you’re the upstart, launching only the vaporware of your promises. When you start flying metal, the stakes go way up—and the rhetoric, accordingly, goes way down. Elon, welcome to the big leagues.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com